The Rhetoric of White Supremacist Terror: Assessing the Attribution of Threat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: a Hoax to Hate Introduction

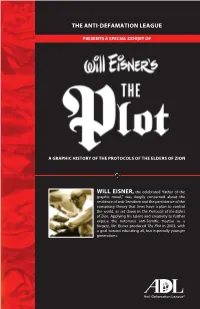

THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE PRESENTS A SPECIAL EXHIBIT OF A GRAPHIC HISTORY OF THE PROTOCOLS OF THE ELDERS OF ZION WILL EISNER, the celebrated “father of the graphic novel,” was deeply concerned about the resilience of anti-Semitism and the persistence of the conspiracy theory that Jews have a plan to control the world, as set down in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Applying his talent and creativity to further expose the notorious anti-Semitic treatise as a forgery, Mr. Eisner produced The Plot in 2003, with a goal toward educating all, but especially younger generations. A SPECIAL EXHIBIT PRESENTED BY THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE ADL is proud to present a special traveling exhibit telling the story of the infamous forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, that has been used to justify anti-Semitism up to and including today. In 2005, Will Eisner’s graphic novel, The Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion was published, exposing the history of The Protocols and raising public awareness of anti-Semitism. Mr. Eisner, who died in 2005, did not live to see this highly effective exhibit, but his commitment and spirit shine through every panel of his work on display. This project made possible through the support of the Will Eisner Estate and W.W. Norton & Company Inc. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: A Hoax to Hate Introduction It is a classic in the literature of hate. Believed by many to be the secret minutes of a Jewish council called together in the last years of the 19th century, it has been used by anti-Semites as proof that Jews are plotting to take over the world. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

The Culture of Wikipedia

Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia Good Faith Collaboration The Culture of Wikipedia Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. Foreword by Lawrence Lessig The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web edition, Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. CC-NC-SA 3.0 Purchase at Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | IndieBound | MIT Press Wikipedia's style of collaborative production has been lauded, lambasted, and satirized. Despite unease over its implications for the character (and quality) of knowledge, Wikipedia has brought us closer than ever to a realization of the centuries-old Author Bio & Research Blog pursuit of a universal encyclopedia. Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a rich ethnographic portrayal of Wikipedia's historical roots, collaborative culture, and much debated legacy. Foreword Preface to the Web Edition Praise for Good Faith Collaboration Preface Extended Table of Contents "Reagle offers a compelling case that Wikipedia's most fascinating and unprecedented aspect isn't the encyclopedia itself — rather, it's the collaborative culture that underpins it: brawling, self-reflexive, funny, serious, and full-tilt committed to the 1. Nazis and Norms project, even if it means setting aside personal differences. Reagle's position as a scholar and a member of the community 2. The Pursuit of the Universal makes him uniquely situated to describe this culture." —Cory Doctorow , Boing Boing Encyclopedia "Reagle provides ample data regarding the everyday practices and cultural norms of the community which collaborates to 3. Good Faith Collaboration produce Wikipedia. His rich research and nuanced appreciation of the complexities of cultural digital media research are 4. The Puzzle of Openness well presented. -

Aryan Nations/Church of Jesus Christ Christian

Aryan Nations/Church of Jesus Christ Christian This document is an archived copy of an older ADL report and may not reflect the most current facts or developments related to its subject matter. INTRODUCTION Recent years have not been kind to Aryan Nations, once the country's most well-known neo-Nazi outpost. Bankrupted by a lawsuit from a mother and son who were assaulted by Aryan Nations guards, the group lost its Idaho compound in 2001. Though he continued to serve as Aryan Nations’ leader, Richard Butler suffered the effects of age and ill health, and the group splintered into factions in 2002. Butler claimed to be reorganizing Aryan Nations but died in September 2004, leaving the group’s future as uncertain as ever. Founder and Leader: Richard Butler (1918-2004) Splinter groups (and leaders): Tabernacle of Phineas Priesthood ( Charles Juba, based in Pennsylvania); Church of the Sons of Yahweh (Morris Gullett, based in Louisiana) Founded: Mid-1970s Headquarters : Hayden, Idaho Background: Butler first became involved with the Christian Identity movement after serving in the U.S. Air Force during World War II. He studied under Wesley Swift, founder of the Church of Jesus Christ Christian, until Swift died. Butler then formed Aryan Nations. Media: Internet, videos, posters, e-mail, chat rooms, online bulletin boards, conferences. Ideology: Christian Identity, white supremacy, neo-Nazi, paramilitary Connections: Aryan Nations has had members in common with several other white supremacist and neo-Nazi groups, including National Alliance, the Ku Klux Klan and The Silent Brotherhood/The Order Recent Developments: Once the most well-known neo-Nazi group in the United States, Aryan Nations has suffered substantially in recent years due to Butler’s ill health, and a lawsuit that cost the group its Northern Idaho compound in 2001. -

Identitarian Movement

Identitarian movement The identitarian movement (otherwise known as Identitarianism) is a European and North American[2][3][4][5] white nationalist[5][6][7] movement originating in France. The identitarians began as a youth movement deriving from the French Nouvelle Droite (New Right) Génération Identitaire and the anti-Zionist and National Bolshevik Unité Radicale. Although initially the youth wing of the anti- immigration and nativist Bloc Identitaire, it has taken on its own identity and is largely classified as a separate entity altogether.[8] The movement is a part of the counter-jihad movement,[9] with many in it believing in the white genocide conspiracy theory.[10][11] It also supports the concept of a "Europe of 100 flags".[12] The movement has also been described as being a part of the global alt-right.[13][14][15] Lambda, the symbol of the Identitarian movement; intended to commemorate the Battle of Thermopylae[1] Contents Geography In Europe In North America Links to violence and neo-Nazism References Further reading External links Geography In Europe The main Identitarian youth movement is Génération identitaire in France, a youth wing of the Bloc identitaire party. In Sweden, identitarianism has been promoted by a now inactive organisation Nordiska förbundet which initiated the online encyclopedia Metapedia.[16] It then mobilised a number of "independent activist groups" similar to their French counterparts, among them Reaktion Östergötland and Identitet Väst, who performed a number of political actions, marked by a certain -

Al-QAEDA and the ARYAN NATIONS

Al-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCAULDIAN PERSPECTIVE by HUNTER ROSS DELL Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON DECEMBER 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For my parents, Charles and Virginia Dell, without whose patience and loving support, I would not be who or where I am today. November 10, 2006 ii ABSTRACT AL-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCALTIAN PERSPECTIVE Publication No. ______ Hunter Ross Dell, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2006 Supervising Professor: Alejandro del Carmen Using Foucauldian qualitative research methods, this study will compare al- Qaeda and the Aryan Nations for similarities while attempting to uncover new insights from preexisting information. Little or no research had been conducted comparing these two organizations. The underlying theory is that these two organizations share similar rhetoric, enemies and goals and that these similarities will have implications in the fields of politics, law enforcement, education, research and United States national security. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School THE

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School THE ORGANIZATIONAL LANDSCAPE OF WHITE SUPREMACY A Thesis in Sociology by Isaiah Gerber Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science December 2019 ii The thesis of Isaiah Gerber was reviewed and approved* by the following: Gary Adler Assistant Professor of Sociology Thesis Advisor John McCarthy Distinguished Professor of Sociology Charles Seguin Assistant Professor of Sociology and Social Data Analytics Jennifer Van Hook Roy C. Buck Professor of Sociology and Demography Director, Graduate Program in Sociology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Little past research has examined how the partitioning of the white supremacist social movement industry (SMI) compares to other SMIs. This is in spite of evidence that organizations within this SMI may be unique in their deployment of protest tactics and willingness to utilize violence. Scholarly analysis of other SMIs indicates that identifying diversity in organizational characteristics like professionalization, membership, frames, and organizational strategies is useful for partitioning SMIs. By evaluating the white supremacist SMI in terms of these four organizational characteristics, this study finds substantial evidence that there are eight distinct organizational clusters operating within the white supremacist SMI, that this diversity is driven by deployed organizational strategies, and that this SMI is unique in its use of violence and willingness to deploy a merchandizing-based organizational strategy. These findings provide both an alternative framework through which to understand diversity in the SMI of white supremacy, as well as evidence that the SMI of white supremacy is distinct within the US social movement sector in its deployment of violence and the merchandizing organizational strategies. -

Transnational Neo-Nazism in the Usa, United Kingdom and Australia

TRANSNATIONAL NEO-NAZISM IN THE USA, UNITED KINGDOM AND AUSTRALIA PAUL JACKSON February 2020 JACKSON | PROGRAM ON EXTREMISM About the Program on About the Author Extremism Dr Paul Jackson is a historian of twentieth century and contemporary history, and his main teaching The Program on Extremism at George and research interests focus on understanding the Washington University provides impact of radical and extreme ideologies on wider analysis on issues related to violent and societies. Dr. Jackson’s research currently focuses non-violent extremism. The Program on the dynamics of neo-Nazi, and other, extreme spearheads innovative and thoughtful right ideologies, in Britain and Europe in the post- academic inquiry, producing empirical war period. He is also interested in researching the work that strengthens extremism longer history of radical ideologies and cultures in research as a distinct field of study. The Britain too, especially those linked in some way to Program aims to develop pragmatic the extreme right. policy solutions that resonate with Dr. Jackson’s teaching engages with wider themes policymakers, civic leaders, and the related to the history of fascism, genocide, general public. totalitarian politics and revolutionary ideologies. Dr. Jackson teaches modules on the Holocaust, as well as the history of Communism and fascism. Dr. Jackson regularly writes for the magazine Searchlight on issues related to contemporary extreme right politics. He is a co-editor of the Wiley- Blackwell journal Religion Compass: Modern Ideologies and Faith. Dr. Jackson is also the Editor of the Bloomsbury book series A Modern History of Politics and Violence. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Program on Extremism or the George Washington University. -

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: Lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet Alexander B. Stohler FacultyAdviser: Dr, Dennis Klein r'^dw May 13,2020 )ol, Masters of Arts in Holocaust & Genocide Studies Kean University In partialfulfillumt of the rcquirementfar the degee of Moster of A* Abstract: I focused my research on modern, American hate groups. I found some criteria for early- warning signs of antisemitic, bigoted and genocidal activities. I included a summary of neo-Nazi and white supremacy groups in modern American and then moved to a more specific focus on contemporary and prominent groups like Atomwaffen Division, the Proud Boys, the Vinlanders Social Club, the Base, Rise Against Movement, the Hammerskins, and other prominent antisemitic and hate-driven groups. Trends of hate-speech, acts of vandalism and acts of violence within the past fifty years were examined. Also, how law enforcement and the legal system has responded to these activities has been included as well. The different methods these groups use for indoctrination of younger generations has been an important aspect of my research: the consistent use of hate-rock and how hate-groups have co-opted punk and hardcore music to further their ideology. Live-music concerts and festivals surrounding these types of bands and how hate-groups have used music as a means to fund their more violent activities have been crucial components of my research as well. The use of other forms of music and the reactions of non-hate-based artists are also included. The use of the internet, social media and other digital means has also be a primary point of discussion. -

4 Annual Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States in 1999

4th Annual Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States in 1999 · Cooperation · Conflict · Human Interest · Shared Experiences Foreword by Hugh Price, President, The National Urban League Introduction by Rabbi Marc Schneier, President, The Foundation For Ethnic Understanding 1 The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding 1 East 93rd Street, Suite 1C, New York, New York 10128 Tel. (917) 492-2538 Fax (917) 492-2560 www.ffeu.org Rabbi Marc Schneier, President Joseph Papp, Founding Chairman Darwin N. Davis, Vice President Stephanie Shnay, Secretary Edward Yardeni, Treasurer Robert J. Cyruli, Counsel Lawrence D. Kopp, Executive Director Meredith A. Flug, Deputy Executive Director Dr. Philip Freedman, Director Of Research Tamika N. Edwards, Researcher The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding began in 1989 as a dream of Rabbi Marc Schneier and the late Joseph Papp committed to the belief that direct, face- to-face dialogue between ethnic communities is the most effective path towards the reduction of bigotry and the promotion of reconciliation and understanding. Research and publication of the 4th Annual Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States was made possible by a generous grant from Philip Morris Companies. 2 FOREWORD BY HUGH PRICE PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL URBAN LEAGUE I am honored to have once again been invited to provide a foreword for The Foundation for Ethnic Understanding's 4th Annual "Report on Black/Jewish Relations in the United States. Much has happened during 1999 and this year's comprehensive study certainly attests to that fact. I was extremely pleased to learn that a new category “Shared Experiences” has been added to the Report.