The Medway's Megalithic Long Barrows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Medway Megaliths and Neolithic Kent

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society THE MEDWAY MEGALITHS AND NEOLITHIC KENT* ROBIN HOLGATE, B.Sc. INTRODUCTION The Medway megaliths constitute a geographically well-defined group of this Neolithic site-type1 and are the only megalithic group in eastern England. Previous accounts of these monuments2 have largely been devoted to their morphology and origins; a study in- corporating current trends in British megalithic studies is therefore long overdue. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN BRITISH MEGALITHIC STUDIES Until the late 1960s, megalithic chambered barrows and cairns were considered to have functioned purely as tombs: they were the burial vaults and funerary monuments for people living in the fourth and third millennia B.C. The first academic studies of these monuments therefore concentrated on the typological analysis of their plans. This method of analysis, though, has often produced incorrect in- terpretations: without excavation it is often impossible to reconstruct the sequence of development and original appearance for a large number of megaliths. In addition, plan-typology disregards other aspects related to them, for example constructional * I am indebted to Peter Drewett for reading and commenting on a first draft of this article; naturally I take responsibility for all the views expressed. 1 G.E. Daniel, The Prehistoric Chamber Tombs of England and Wales, Cambridge, 1950, 12. 2 Daniel, op. cit; J.H. Evans, 'Kentish Megalith Types', Arch. Cant, Ixiii (1950), 63-81; R.F. Jessup, South-East England, London, 1970. 221 THE MEDWAY MEGALITHS GRAVESEND. ROCHESTER CHATHAM r>v.-5rt AYLESFORD MAIDSTONE Fig. -

The Origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 the Avebury Henge Is One of the Famous Mega

1 The origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2Mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 The Avebury henge is one of the famous mega- 7 lithic monuments of the European Neolithic, Research 8 yet much remains unknown about the detail 9 and chronology of its construction. Here, the 10 results of a new geophysical survey and 11 re-examination of earlier excavation records 12 illuminate the earliest beginnings of the 13 monument. The authors suggest that Ave- ’ 14 bury s Southern Inner Circle was constructed 15 to memorialise and monumentalise the site ‘ ’ 16 of a much earlier foundational house. The fi 17 signi cance here resides in the way that traces 18 of dwelling may take on special social and his- 19 torical value, leading to their marking and 20 commemoration through major acts of monu- 21 ment building. 22 23 Keywords: Britain, Avebury, Neolithic, megalithic, memory 24 25 26 Introduction 27 28 Alongside Stonehenge, the passage graves of the Boyne Valley and the Carnac alignments, the 29 Avebury henge is one of the pre-eminent megalithic monuments of the European Neolithic. ’ 30 Its 420m-diameter earthwork encloses the world s largest stone circle. This in turn encloses — — 31 two smaller yet still vast megalithic circles each approximately 100m in diameter and 32 complex internal stone settings (Figure 1). Avenues of paired standing stones lead from 33 two of its four entrances, together extending for approximately 3.5km and linking with 34 other monumental constructions. Avebury sits within the centre of a landscape rich in 35 later Neolithic monuments, including Silbury Hill and the West Kennet palisade enclosures 36 (Smith 1965; Pollard & Reynolds 2002; Gillings & Pollard 2004). -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

The Medway Valley Prehistoric Landscapes Project

AST NUMBER 72 November 2012 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY Registered Office University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, London WC1H 0PY http://www.prehistoricsociety.org/ PTHE MEDWAY VALLEY PREHISTORIC LANDSCAPES PROJECT The Early Neolithic megalithic monuments of the Medway valley in Kent have a long history of speculative antiquarian and archaeological enquiry. Their widely-assumed importance for understanding the earliest agricultural societies in Britain, despite how little is really known about them, probably stems from the fact that they represent the south-easternmost group of megalithic sites in the British Isles and have figured - usually in passing - in most accounts of Neolithic monumentality since Stukeley drew Kit’s Coty House in 1722. Remarkably, this distinctive group of monuments and other major sites (such as Burham causewayed enclosure) have not previously been subject to a Kit’s Coty House: integrated laser scan and ground-penetrating landscape-scale programme of investigation, while the radar survey of the east end of the monument only significant excavation of a megalithic site in the region took place over 50 years ago (by Alexander at the The Medway Valley Project aims to establish a new Chestnuts in 1957). The relative neglect of the area, and interpretative framework for the Neolithic archaeology its research potential, have been thrown into sharper of the Medway valley, focusing on the architectural relief recently by the discovery of two Early Neolithic forms, chronologies and use-histories of monuments, long halls nearby at White Horse Stone/Pilgrim’s Way and changes in environment and inhabitation during the on the High Speed 1 route, and by the radiocarbon period c. -

The Landscape Archaeology of Martin Down

The Landscape Archaeology of Martin Down Martin Down and the surrounding area contain a variety of well‐preserved archaeological remains, largely because the area has been unaffected by modern agriculture and development. This variety of site types and the quality of their preservation are relatively unusual in the largely arable landscapes of central southern England. Bokerley Dyke, Grim's Ditch, the short section of medieval park boundary bank and the two bowl barrows west of Grim's Ditch, form the focus of the Martin Down archaeological landscape and, as such, have been the subject of part excavations and a detailed survey by the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England. These investigations have provided much information about the nature and development of early land division, agriculture and settlement within this area during the later prehistoric and historic periods. See attached map for locations of key sites A ritual Neolithic Landscape….. Feature 1. The Dorset Cursus The Cursus dates from 3300 BCE which makes it contemporary with the earthen long barrows on Cranborne Chase: many of these are found near, on, or within the Cursus and since they are still in existence they help trace the Cursus' course in the modern landscape. The relationship between the Cursus and the alignment of these barrows suggests that they had a common ritual significance to the Neolithic people who spent an estimated 0.5 million worker‐hours in its construction. A cursus circa 6.25 miles (10 kilometres) long which runs roughly southwest‐northeast between Thickthorn Down and Martin Down. Narrow and roughly parallel‐sided, it follows a slightly sinuous course across the chalk downland, crossing a river and several valleys. -

Megaliths, Monuments & Tombs of Wessex & Brittany

From Stonehenge to Carnac: Megaliths, Monuments & Tombs of Wessex & Brittany Menhhir du Champs Dolent SLM (1).JPG May 25 - June 5, 2021 (12 days | 14 guests) with prehistorian Paul G. Bahn © Jane Waldbaum ©Vigneron ©AAlphabet © DChandra © DBates Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur “The special tour of Stonehenge was a highlight, as well as visiting the best of the best of prehistoric sites with Archaeological Institute an immensely knowledgeable guide like Paul Bahn.” of America - Grant, Ontario Lecturer xplore the extraordinary prehistoric sites of Wessex, England, & Host and Brittany, France. Amidst beautiful landscapes see world renowned, as well as lesser known, Neolithic and Bronze Age Emegaliths and monuments such as enigmatic rings of giant standing stones and remarkable chambered tombs. Dr. Paul G. Bahn is a leading archaeological writer, translator, and broadcaster in the Highlights: field of archaeology. He is a Contributing Editor of the AIA’s Archaeology magazine, • Stonehenge, the world’s most famous megalithic site, which is a and has written extensively on prehistoric UNESCO World Heritage site together with Avebury, a unique art, including the books Images of the Ice Neolithic henge that includes Europe’s largest prehistoric stone circle. Age, The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art, and Cave Art: A Guide to • Enigmatic chambered tombs such as West Kennet Long Barrow. the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe. Dr. • Carnac, with more than 3,000 prehistoric standing stones, the Bahn has also authored and/or edited many world’s largest collection of megalithic monuments. books on more general archaeological subjects, bringing a broad perspective to • The uninhabited island of Gavrinis, with a magnificent passage tomb understanding the sites and museums that is lined with elaborately engraved, vertical stones. -

Prehistoric Hilltop Settlement in the West of Ireland Number 89 Summer

THE NEWSLETTERAST OF THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY P Registered Office: University College London, Institute of Archaeology, 31–34 Gordon Square, London WC1H 0PY http://www.prehistoricsociety.org/ Prehistoric hilltop settlement in the west of Ireland For two weeks during the summer of 2017, from the end footed roundhouses were recorded on the plateau, and further of July through the first half of August, an excavation was structures were identified in a survey undertaken by Margie carried out at three house sites on Knocknashee, Co. Sligo, Carty from NUI Galway during the early 2000s, bringing by a team from Queen’s University Belfast. Knocknashee the total to 42 roundhouses. is a visually impressive flat-topped limestone hill rising 261 m above the central Sligo countryside. Archaeologists However, neither of these two surveys was followed up by have long been drawn to the summit of Knocknashee excavation, and as the boom of development-driven archae- because of the presence of two large limestone cairns to the ology during the Celtic Tiger years has largely spared exposed north of the plateau, and aerial photographs taken by the hilltop locations, our archaeological knowledge not only of Cambridge University Committee for Aerial Photography Knocknashee, but also of prehistoric hilltop settlements in in the late 1960s also identified an undetermined number Ireland more widely remains relatively limited in comparison of prehistoric roundhouses on the summit. During survey to many other categories of site. This lack of knowledge work undertaken -

The Long Barrows and Long Mounds of West Mendip

Proc. Univ. Bristol Spelaeol. Soc., 2008, 24 (3), 187-206 THE LONG BARROWS AND LONG MOUNDS OF WEST MENDIP by JODIE LEWIS ABSTRACT This article considers the evidence for Early Neolithic long barrow construction on the West Mendip plateau, Somerset. It highlights the difficulties in assigning long mounds a classification on surface evidence alone and discusses a range of earthworks which have been confused with long barrows. Eight possible long barrows are identified and their individual and group characteristics are explored and compared with national trends. Gaps in the local distribution of these monuments are assessed and it is suggested that areas of absence might have been occupied by woodland during the Neolithic. The relationship between long barrows and later round barrows is also considered. INTRODUCTION Long barrows are amongst the earliest monuments to have been built in the Neolithic period. In Southern Britain they take two forms: non-megalithic (or “earthen”) long barrows and megalithic barrows, mostly belonging to the Cotswold-Severn tradition. Despite these differences in architectural construction, the long mounds are of the same, early 4th millennium BC, date and had a similar purpose. The chambers of the long mounds were used for the deposition of the human dead and the monuments themselves appear to have acted as a focus for ritual activities and religious observations by the living. Some long barrows show evidence of fire lighting, feasting and deposition in the forecourts and ditches of the monuments, and alignment upon solstice events has also been noted. A local example of this can be observed at Stoney Littleton, near Bath, where the entrance and passage of this chambered long barrow are aligned upon the midwinter sunrise1. -

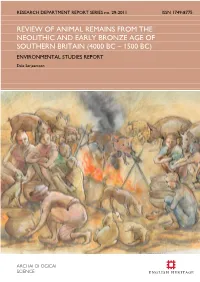

Neolithic Report

RESEARCH DEPARTMENT REPORT SERIES no. 29-2011 ISSN 1749-8775 REVIEW OF ANIMAL REMAINS FROM THE NEOLITHIC AND EARLY BRONZE AGE OF SOUTHERN BRITAIN (4000 BC – 1500 BC) ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES REPORT Dale Serjeantson ARCHAEOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Department Report Series 29-2011 REVIEW OF ANIMAL REMAINS FROM THE NEOLITHIC AND EARLY BRONZE AGE OF SOUTHERN BRITAIN (4000 BC – 1500 BC) Dale Serjeantson © English Heritage ISSN 1749-8775 The Research Department Report Series, incorporates reports from all the specialist teams within the English Heritage Research Department: Archaeological Science; Archaeological Archives; Historic Interiors Research and Conservation; Archaeological Projects; Aerial Survey and Investigation; Archaeological Survey and Investigation; Architectural Investigation; Imaging, Graphics and Survey; and the Survey of London. It replaces the former Centre for Archaeology Reports Series, the Archaeological Investigation Report Series, and the Architectural Investigation Report Series. Many of these are interim reports which make available the results of specialist investigations in advance of full publication. They are not usually subject to external refereeing, and their conclusions may sometimes have to be modified in the light of information not available at the time of the investigation. Where no final project report is available, readers are advised to consult the author before citing these reports in any publication. Opinions expressed in Research Department Reports are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of English Heritage. Requests for further hard copies, after the initial print run, can be made by emailing: [email protected]. or by writing to English Heritage, Fort Cumberland, Fort Cumberland Road, Eastney, Portsmouth PO4 9LD Please note that a charge will be made to cover printing and postage. -

The Research History of Long Barrows in Russia and Estonia in the 5Th –10Th Centuries

Slavica Helsingiensia 32 Juhani Nuorluoto (ed., ., Hrsg.) Topics on the Ethnic, Linguistic and Cultural Making of the Russian North , Beiträge zur ethnischen, sprachlichen und kulturellen Entwicklung des russischen Nordens Helsinki 2007 ISBN 978–952–10–4367–3 (paperback), ISBN 978–952–10–4368–0 (PDF), ISSN 0780–3281 Andres Tvauri (Tartu) Migrants or Natives? The Research History of Long Barrows in Russia and Estonia in the 5th –10th Centuries Introduction The central problem in the history of North-Western Russia is how the area became Slavic. About 700–1917 AD Finno-Ugric and Baltic heathen autochthons turned into Orthodox Russians speaking mostly Slavic languages. Scholars have up to now been unable to clarify when, how, and why that process took place. Archaeologists have addressed the question of how Slavicization began in South-Western Russia by researching primarily graves, which represent the most widespread type of sites from the second half of the first millennium AD. During the period from the 5th to the 10th century, the people of North-Western Russia, South-Eastern Estonia, Eastern Latvia, and North-Eastern Belarus buried part of their dead in sand barrows, which were mostly erected in groups on the banks of river valleys, usually in sandy pine forests. Such barrows are termed long barrows. The shape of the barrows and burial customs vary considerably in their distribution area. Both round and long barrows were erected. The barrows are usually dozens of metres in length, in exceptional cases even a hundred metres, and their height is most often between 0.5–1 m. In such cemeteries, the cremation remains of the dead were buried either in a pit dug in the ground beneath the later barrow, placed on the ground below the barrow, or in the already existing sand barrow. -

Maidstone Area Archaeological Group, Should Be Sent to Jess Obee (Address at End) Or Payments Made at One of the Meetings

Maidstone Area Archaeological Group Newsletter, March 2000 Dear Fellow Members As there is a host of announcements, I will hold over the Editorial until the next Newsletter, due in May (sighs of relief all round). David Carder Subscriptions and Membership Cards Subscriptions for the year beginning 1st April 2000 are now due. Please use the renewal form enclosed with this Newsletter, and complete as much as of it as possible - that way we can establish what members' interests really are. Return the form with your cheque by post to Jess Obee (address at end), or hand it with cheque or cash to any Committee Member who will give you a receipt. Renewing members will receive a handy Membership Card with the May Newsletter, giving details of indoor meetings, subscription rates, and contacts. In order to comply with the data protection legislation, we have included on the form a consent that your details may be held on a computer database. This data is held purely for membership administration (e.g. printing of address labels and registration of subscription payments). It will not be used for other purposes, or released to outside parties without your express consent. If you have any queries or concerns over this, please write to the Chairman. Notice of Annual General Meeting - Friday 28th April 2000 This year's AGM will be held at 7.30 pm on Friday 28th April 2000 (not 21st as previously published) at the School Hall, The Street, Detling. The Agenda is as follows : 1. Chairman's welcome 2. Apologies for absence 3. -

Ancient Genomes Indicate Population Replacement in Early Neolithic Britain

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATIONARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0871-9 In the format provided by the authors and unedited. Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain Selina Brace1,15, Yoan Diekmann2,15, Thomas J. Booth1,15, Lucy van Dorp 3, Zuzana Faltyskova2, Nadin Rohland4, Swapan Mallick3,5,6, Iñigo Olalde4, Matthew Ferry4,6, Megan Michel4,6, Jonas Oppenheimer4,6, Nasreen Broomandkhoshbacht4,6, Kristin Stewardson4,6, Rui Martiniano 7, Susan Walsh8, Manfred Kayser 9, Sophy Charlton 1,10, Garrett Hellenthal3, Ian Armit 11, Rick Schulting12, Oliver E. Craig 10, Alison Sheridan13, Mike Parker Pearson14, Chris Stringer 1, David Reich4,5,6,16, Mark G. Thomas 2,3,16* and Ian Barnes 1,16* 1Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, London, UK. 2Research Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, University College London, London, UK. 3UCL Genetics Institute, University College London, London, UK. 4Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. 5Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA. 6Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. 7Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 8Department of Biology, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, USA. 9Department of Genetic Identification, Erasmus University Medical Centre Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. 10Bioarch, University of York, York, UK. 11School of Archaeological and Forensic Sciences, University of Bradford, Bradford, UK. 12Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. 13National Museums Scotland, Edinburgh, UK. 14Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London, UK. 15These authors contributed equally: Selina Brace, Yoan Diekmann, Thomas J. Booth. 16These authors jointly supervised this work: David Reich, Mark G.