Still Riding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gerry Dilger Passes Away

THURSDAY, MARCH 5, 2020 GERRY DILGER MCLAUGHLIN LEAVING TRAINING TO BECOME SAEZ'S AGENT PASSES AWAY by Bill Finley Despite being one of the sport's most successful trainers, Kiaran McLaughlin has decided to switch jobs and has signed on with Luis Saez to be his agent. McLaughlin will continue to train through the end of this month, before going to work for Saez Apr. 1. "I was approached about taking Luis Saez' book and after speaking to my wife, my children, my family, I felt like this was the right thing to do," McLaughlin said. "I am very excited. Luis is a great kid and a great jockey." Cont. p5 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY TRAINER/BREEDER JOE CROWLEY PASSES Respected trainer/breeder Joe Crowley passed away at 91. Gerry Dilger | Fasig-Tipton John Berry has the story. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. by Christie DeBernardis Breeder, consignor and Dromoland Farm owner Gerry Dilger passed away very early Wednesday morning. The 61-year-old had been hospitalized in the ICU since suffering from cardiac arrest Feb. 24, confirmed Dilger=s longtime friend and business partner Mike Ryan. AWe were best friends for over 40 years,@ Ryan said. AIt is quite sudden and a big shock to us all. He was a very, very kind man and did so much for so many people. He would give you the shirt off his back. Gerry took tremendous personal pride in bringing students from Ireland, who aspired to be successful in the horse business, to work on his farm. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 5/3/09 • PAGE 2 of 18

HEADLINE THREE CHIMNEYS NEWS The Idea is Excellence. For information about TDN, Three Chimneys Congratulates call 732-747-8060. Calvin Borel on His Oaks/Derby Double! www.thoroughbreddailynews.com SUNDAY, MAY 3, 2009 TDN Feature Presentation REVENGE WILL HAVE TO WAIT Morning-line favorite I Want Revenge (Stephen Got GRADE 1 KENTUCKY DERBY Even) was scratched from the GI Kentucky Derby after heat was detected in his left front ankle. AWe detected a little pressure and a touch of heat in the left front ankle,@ trainer Jeff Mullins explained. AWe jogged him up and down the asphalt to check for soundness, and he actually jogged pretty well. We flexed the ankle and A DELIGHTFUL DERBY DAY! he gave to the flexing of the ankle. By that time, Dr. SMART STRIKE: BDM. SIRE OF MINE THAT BIRD - 1ST KENTUCKY DERBY Foster [Northrop] showed up. He jogged him again and LEMON DROP KID: BRONZE CANNON-G2W & COSMONAUT-G3W A.P. INDY: FLASHING-G3W he jogged fairly good. Dr. Foster flexed the ankle and MINESHAFT: MINER’S ESCAPE - LISTED STAKES WINNER he gave to the flexion again.@ The veterinarian added, AOn the digital X-rays, I=m not seeing any bone lesion at THE ULTIMATE RAILBIRD all. It X-rays really pristine, so I do think it=s more soft One day after piloting 1-5 Rachel Alexandra (Medaglia tissue at this point. Ultrasound, which is basically an d=Oro) to a dominant victory in X-ray on soft tissue, I=m not seeing a lesion either. So the GI Kentucky Oaks, jockey further diagnostics will be done.@ Cont. -

Congressional Record—Senate S6143

May 15, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S6143 critical change—it’s the U.S.-China SUBMITTED RESOLUTIONS Spun in the stretch and draw away to a 21⁄4- Commission and the GAO as well. length victory; When my amendment stalled over a Whereas the victory was Calvin Borel’s SENATE RESOLUTION 199—CALL- first in the Kentucky Derby; committee jurisdictional point, on Sep- ING FOR THE IMMEDIATE AND Whereas Calvin Borel was born on Novem- tember 29, 2005, I chose to introduce UNCONDITIONAL RELEASE OF ber 7, 1966, in St. Martinsville, Louisiana; the changes as a stand-alone bill, the DR. HALEH ESFANDIARI Whereas Calvin Borel hails from South Foreign Investment Security Act of Louisiana, the heart of Cajun Country, fa- 2005, S. 1797, which was referred to the Mr. SMITH (for himself and Mrs. mous for its production of many top jockeys Banking Committee. That bill was the CLINTON) submitted the following reso- during the last 20 years; and first bill introduced in recent years on lution; which was referred to the Com- Whereas Calvin Borel’s victory in the 133rd this topic. mittee on Foreign Relations. running of the Kentucky Derby solidifies his place in a tradition of Louisiana jockeys who S. RES. 199 Later the Banking Committee held a have won the Kentucky Derby, such as Eric hearing on the GAO report, and I testi- Whereas Dr. Haleh Esfandiari is one of the Guerin (1947), Edward Delahoussaye (1982, fied before them on October 20, 2005, at United States’s most distinguished analysts 1983), Craig Perret (1990), and Kent that hearing. -

KENTUCKY OAKS DAY America’S Greatest Springtime Sports Party

KENTUCKY OAKS DAY America’s greatest springtime sports party. In 2009, it stepped out of the Derby’s shadow to become an Kentucky Oaks Day is the third largest American sports classic in its own right with a attended horse race in America only behind the “Ladies First ” theme, complete with a “ Pink Out ” Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes and Belmont and a focus on fashion and important causes. Stakes. “Kentucky Oaks Day has always celebrated the The Friday afternoon program at Churchill top female equine athletes in our sport, and so Oaks Downs on the day before the Kentucky Derby – an Day is a natural opportunity for us to reach out to unofficial Louisville holiday with many schools and women around the world and encourage them to join businesses closed – has blossomed in recent decades. us for a great day of racing, entertainment and In 1980, Oaks Day attendance was 49,556. Three awareness of issues that matter most to them,” decades later, a record 124,589 attended the 2016 Robert L. Evans , chairman and chief executive festivities, which marked the 16th time in the last 17 officer of Churchill Downs Incorporated said in years that attendance topped 100,000. 2009. Wagering on the 13-race card in 2016 was an “The Oaks is one of those coveted races that all unprecedented $49,048,611, and more than $ X trainers would like to win,” said Hall of Fame trainer million was wagered on the Oaks alone, which also D. Wayne Lukas , who has trained four Kentucky was a record. Oaks winners. -

CHD-4417.Ver.4

CDI employees starting at the top, from left to right: Sandi Ho, Tram Vo, Talice Berry, Irene Rodriguez, Patti Boggs, Erin Moen, Angela Manalansan, Mark Fritsche, Shelley Robinson, Princess Van Sickle; all of Hollywood Park’s accounting department – Mike Kohan, general manager at the Merrillville Sports Spectrum – Freddy Lee Smith, Calder security – Bruce Kincaid, backside maintenance at Churchill Downs – Yolanda Buford, human resources manager; Scott Graff, controller; Vicki Baumgardner, vice president, finance, and treasurer; all of Churchill Downs – Dannette Brennan-Smith, Hollywood Park human resources. 2 Churchill Downs Incorporated Letter to our Stockholders President and Chief Executive Thomas H. Meeker and Chairman William S. Farish 1999 Annual Report 3 1999 was the year in which our planning and our commitment to excellence resulted in outstanding progress for Churchill Downs Incorporated. Aided by strategic acquisitions, we achieved record financial results, we reinforced our leadership in the racing industry, and we continued our development of a comprehensive simulcast product. These accomplishments underscore the value of our four-prong business strategy, which continues to guide us as we embark on an era in our industry that will be defined by marketing innovations and technological advances. With progress comes change. Two years ago, our operations were centered in Indiana and Kentucky. We now have five racetracks in four states, including California and Florida. The acquisitions of Calder Race Course and Hollywood Park more than tripled the size of our Company’s assets. In 1997, we had a staff of 325 full-time employees; now we employ 1,000 people full time. To support this growth, the integration of our new properties and any future expansion plans, the Company has built a strong managerial infrastructure, and we are dedicating considerable energies to develop cohesiveness in our practices, which allows us to share resources effectively. -

Inside F Interactif Wins with Anticipation F Today’S Entries and Handcapping Tod Marks Photo Claiborne Keeneland Farm at September

SUBSCR FREE ER IPT IN IO A N R S T COMPLIMENTS OF T ARATOGA O L T IA H C E The E S P S ARATOGA Year 9 • No. 31 SARATOGA’S DAILY NEWSPAPER ON THOROUGHBRED RACING Saturday, September 5, 2009 Hey Guys Rachel Alexandra headlines the Woodward Inside F Interactif wins With Anticipation F Today’s entries and handcapping Tod Marks Photo Claiborne Keeneland Farm at September Champion ARRAVALE s G2 SW WEND Half-siblings to: Leading Sire PULPIT s 2009 Multiple G1 SW ZENSATIONAL G1 SW LUCIFER’S STONE s G2 SW SPICE ISLAND By Such Sires as: A.P. Indy First Samurai Out of Place Aptitude Flatter Pulpit Arch Forest Wildcat Sky Mesa Broken Vow Forestry Songandaprayer Came Home Giant’s Causeway Street Cry (Ire) City Zip Horse Chestnut (SAf) Strong Hope Dynaformer Johannesburg Touch Gold Eddington Lemon Drop Kid Vindication Empire Maker Mr. Greeley War Front Eurosilver Orientate Yes It’s True Recent Sales Graduates include: Champions WAR PASS, ARRAVALE and two-time 2009 G1 SW ZENSATIONAL Monday, Sept. 14, Barn 6 Tuesday, Sept. 15, Barn 6 Post Offi ce Box 150 Wednesday, Sept. 16, Barn 26 Paris, Kentucky 40362-0150 Monday, Sept. 21, Barn 38 Tel.(859) 233-4252 Fax 987-0008 Wednesday, Sept. 23, Barn 3 claibornefarm.com Friday, Sept. 25, Barn 38 INQUIRIES TO BERNIE SAMS e-mail: [email protected] 90695.CLB.KeeSepSaleSARSpclpg8-29.indd 1 8/28/09 3:07:40 PM 2 Saturday, September 5, 2009 Saturday, September 5, 2009 3 Here & There at Saratoga 517 Broadway, Suite 207 Saratoga Springs, NY 12866 (Second Floor, around the back) Phone: (518) 490-1175 Sean Mobile: (302) 545-7713 Joe Mobile: (302) 545-4424 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Internet: www.saratogaspecial.com Published Wednesday through Sunday during the racing season. -

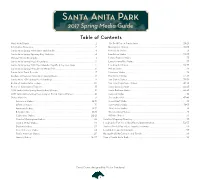

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Commonwealth Stakes (G3) 31St Running • Spring • 7 Furlongs • 4-Year-Olds and Up

Commonwealth Stakes (G3) 31st Running • Spring • 7 furlongs • 4-year-olds and up The Commonwealth is one of the supporting features on the day of the Toyota Blue Grass (G1) during the Spring Meet. Milestones – Commonwealth Stakes 2016 Purse: $250,000 Fastest Time at Current Distance (7 furlongs): 1:20 2/5, Distorted Humor, 1998 Largest Straight Payoff: $66.20, Black Tie Affair (IRE), 1990 Smallest Straight Payoff: $2.60, Richter Scale, 2000 Largest Field: 12, 2006 Smallest Field: 5, 1999; 2010; 2011; 2013 Largest Value to Winner: $274,784, Sun King, 2006 Keeneland/Coady STAKES Ami’s Flatter won the Commonwealth (G3) by 2¾ lengths for his first career stakes win. Keeneland/Coady Kentucky’s Agriculture Commissioner, Ryan Quarles, presented the trophy to jockey Martin Garcia and Ruth Schmidt, assistant to trainer Josie Carroll. Commonwealth Stakes History Year Winner/Age/Owner Jockey/Wgt./Trainer 2nd/Age/Jockey/Wgt. 3rd/Age/Jockey/Wgt. Time Margin 2016 Ami’s Flatter (4) Martin Garcia (118) Ready for Rye (4) Holy Boss (4) 1:21.66 ft 2 3/4 Ivan Dalos Josie Carroll Javier Castellano (120) Florent Geroux (120) 2015 Kobe’s Back (4) Gary Stevens (118) C. Zee (4) Rocket Time (4) 1:22.16 ft 3/4 C R K Stable (Lee Searing) Peter Eurton Edgard Zayas (120) Calvin Borel (118) 2014 Occasional View (6) Alan Garcia (118) Dimension (GB) (6) Laugh Track (5) 1:22.77 ft 1 Robert Trussell Kenneth G. McPeek James Graham (118) Jose Lezcano (118) Polytrack 2013 Handsome Mike (4) Mario Gutierrez (118) Gantry (6) Candyman E (6) 1:23.14 ft 1 1/4 Reddam Racing LLC Doug O’Neill Richard Eramia (118) Joe Bravo (118) Polytrack (J. -

138904 08 Juvenilefillies.Pdf

breeders’ cup JUVENILE FILLIES BREEDERs’ Cup JUVENILE FILLIES (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $2,000,000 Guaranteed FOR FILLIES, TWO-YEARS-OLD ONE MILE AND ONE-SIXTEENTH Weight, 122 lbs. Guaranteed $2 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 22, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Juvenile Fillies (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Artemis Agrotera Chestertown Farm Michael E. Hushion B.f.2 Roman Ruler - Indy Glory by A.P. Indy - Bred in New York by Chester Broman & Mary R. Broman Concave Reddam Racing, LLC Doug O'Neill B.f.2 Colonel John - Galadriel by Ascot Knight - Bred in Ontario by Windways Farm Limited Dancing House Godolphin Racing, LLC Kiaran P. -

Headline News

HEADLINE THREE CHIMNEYS NEWS The Idea is Excellence. For information about TDN, Three Runners for EXCHANGE RATE call 732-747-8060. In Today’s Sunshine Millions Races www.thoroughbreddailynews.com SATURDAY, JANUARY 24, 2009 TDN Feature Presentation LAS VEGAS CASINOS RISK RACING BLACKOUT According to published reports, Las Vegas casinos SUNSHINE MILLIONS CLASSIC will lose the signals from Fair Grounds, Gulfstream Park and Santa Anita beginning Monday if they cannot come to an agreement with TrackNet Media Group. TrackNet, a joint venture between Churchill Downs Inc. and Magna Entertainment Corp., handles the distribution and broadcast of the two companies= simulcasting TWO-TIME LEADING SIRE A.P. INDY’S RISING STARS signals. The contract between TrackNet and the Ne- PINCKNEY HILL - MSW AT GULFSTREAM BY 3 (video) vada Pari-Mutuel Association expired three weeks ago, but was extended through Jan. 25 to accomodate the ASBEAUTIFULASYOU (IRE) - BY 20 1/4 LENGTHS!! (video) National Handicapping Championship, to be held at the Red Rock Casino Resort Friday through Sunday. The BYRN BABY BYRN dispute surrounds the rates paid by Las Vegas casinos Hey Byrn (Put It Back) has always loved Gulfstream, for the simulcast signals, which is below the market and he ll look to run his record at the track to five-for- = rate. The Daily Racing Form reports that, while Vegas six in today=s $1 million accounted for 10 percent of the national handle Sunshine Millions Classic. 10 years ago, they now only bring in 4 percent of the The four-year-old made total. As a result, TrackNet is arguing that they should his Hallandale debut in an allowance test last Febru- pay higher rates. -

The History of Oaklawn Park

The History of Oaklawn Park 1900s Desiring to build a track closer to downtown, John Condon and Dan Stuart, who also ran Southern Club and Turf Exchange, a popular downtown Hot Springs night spot, and brothers Louis and Charles Cella of St. Louis formed the Oaklawn Jockey Club in 1904. Celebrated Chicago architect Zachary Taylor Davis is hired to design Oaklawn’s glass-enclosed, heated grandstand – among the first of its kind in the country. The grandstand reportedly seated 1,500 people and cost $500,000. Davis designed Wrigley Field, the longtime home of the Chicago Cubs, a decade later. Feb. 15, 1905 – The inaugural meet opens and runs through March 18. 1910s March 11, 1916 – Owner Louis A. Cella returns racing to Oaklawn after nine years 1 of political uncertainty in Arkansas. Cella, from St. Louis, was a bookmaker, horseman and financier and started running tracks, both in his hometown and in New Orleans. He later joined his brother, Charles J. Cella in operating Douglas Park and Latonia Race Course in Kentucky. For a time, they challenged the preeminence of Matt Winn and Churchill Downs in the Blue Grass state. Fabled mare Pan Zareta won the feature that opening day and goes 3-for-3 on the meet. March 8, 1917 – After one race in Mexico, Old Rosebud makes a winning debut at Oaklawn, 33 months after winning the Kentucky Derby in 1914. He would win again a week later, but would finish third at 137 lbs. to Pan Zareta at 113 when they met March 24. Old Rosebud would turn the tables April 6 in an allowance race en route to leading the nation in handicap earnings that year. -

Churchill Downs Career Wins, Jockeys Cd Career Stakes Wins, Jockeys

CHURCHILL DOWNS CAREER WINS, JOCKEYS CD CAREER STAKES WINS, JOCKEYS Through 2015 Fall Meet Through 2015 Fall Meet Rank Jockey CD Career Wins Rank Jockey CD Career Stakes Wins 1. Pat Day (Fall 1980-Spring 2005) 2,482 1. Pat Day (Fall 1980-Spring 2005) 156 2. Calvin Borel (Spring 1993-present) 1,189 2. Robby Albarado (Spring 1995-present) 76 3. Robby Albarado (Spring 1995-present) 1,056 3. Calvin Borel (Spring 1993-present) 60 4. Don Brumfield (Fall 1961-Spring 1989) 925 4. Julien Leparoux (Fall 2005-present) 53 5. Larry Melancon (Spring 1974-Spring 2010) 914 5. Shaun Bridgmohan (Spring 2003-present) 47 6. Jim McKnight (Spring 1970-Fall 1998) 883 5. Larry Melancon (Spring 1974-Spring 2010) 47 7. Charlie Woods Jr. (Spring 1976-Fall 2009) 757 7. Don Brumfield (Fall 1961-Spring 1989) 46 8. Shane Sellers (Spring 1991-present) 738 7. Shane Sellers (Spring 1991-present) 46 9. Corey Lanerie (Spring 2000-present) 710 9. Jerry Bailey 38 10. Julien Leparoux (Fall 2005-present) 707 10. John Velazquez (Spring 1996-present) 37 11. Julio Espinoza (Spring 1973-Fall 1998) 642 11. Garrett Gomez 30 12. Shaun Bridgmohan (Spring 2003-present) 621 11. Gary Stevens 30 13. Jon Court (Spring 1996-present) 496 13. Keith Allen (Spring 1983-Spring 1995) 28 14. Patrick Johnson (Spring 1981-present) 467 13. Craig Perret 28 15. Mike McDowell (Spring 1968-Fall 1991) 452 15. Kent Desormeaux 25 16. Willie Martinez (Fall 1992-present) 435 15. Corey Lanerie (Spring 2000-present) 25 17. Keith Allen (Spring 1983-Spring 1995) 431 15.