Which Irish.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beirne O'beirne

Beirne With or without the “0” prefix, the Beirnes are an important sept of North Connacht. They have inhabited northeastern County Roscom- O’Beirne mon beside the Shannon for two millennia. O’Beirne belongs almost exclusively to Connacht. One branch, allied to the MacDermots and the other leading Roscommon families, in the thirteenth century displaced the O’Monahans as chiefs of a territory called Tir Briuin between Elphin and Jamestown on the Co. Roscommon side of the Shannon. The O’Beirnes appear as such in the “Composition Book of Connacht” (1585), and in 1850 there was still an O’Beirne of Dangan-t-Beirn in that territory. The other branch possessed territory in the adjoining county of Mayo, north of Ballinrobe. At the present time, O’Beirnes are chiefly found in Counties Roscommon and Leitrim. The O’Beirnes are predominantly Gaodhail (Milesian) Celts but with blood of the Fir Bolgs (Belgae) and possibly of those Norwegian Vikings who settled on the banks of the Shannon where the O’Beirnes lived and who may have given them their surname. From historic times, some also must have blood of the French or Spanish and many of the English. The “Book of Irish Pedigrees” states that they are de- scended from Milesius of Spain through his son Heremon who reigned in Connacht circa 1700BC. It further records that in the 12th century, the O’Beirnes /O Birns were chiefs of Muintir O’Mannnachain, a ter- ritory along the Shannon from the parish of Ballintober to Elphin in Roscommon. Family Tree DNA and the researchers at the University of Arizona have identified a particular subglade for O’Beirne descen- dants that connects them to a specific area of Roscommon. -

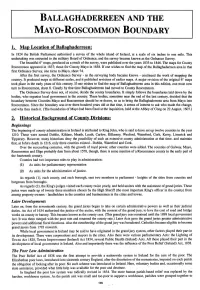

Ballaghaderreen and the Mayo-Roscommon Boundary

..;.. BALLAGHADERREEN AND THE MAYO-ROSCOMMON BOUNDARY h Map Location of Ballaa:haderreen: In 1824 the British Parliament authorised a survey of the whole island of Ireland, at a scale of six inches to one mile. This undertaking was entrusted to the military Board of Ordnance, and the survey became known as the Ordnance Survey. The beautiful 6" maps, produced as a ,result of the survey, were published over the years 1833 to 1846. The maps for County Roscommon appeared in 1837; those for County Mayo in 1838. If one wishes to find the map of the Ballaghaderreen area in that first Ordnance Survey, one turns to Mayo, sheet 74. After the first survey, the Ordnance Survey - as the surveying body became known - continued the work of mapping the country. It produced maps at different scales, and it published revisions of earlier maps. A major revision of the original 6" maps took place in the early years of this century. If one wishes to find the map of Ballaghaderreen area in this edition, one must now tum to Roscommon, sheet 8. Clearly by that time Ballaghaderreen had moved to County Roscommon. The Ordnance Survey does not, of course, decide the county boundaries. It simply follows the boundaries laid down by the bodies, who organise local government in the country. These bodies, sometime near the end of the last century, decided that the boundary between Counties Mayo and Roscommon should be re-drawn, so as to bring the Ballaghaderreen area from Mayo into Roscommon. Since the boundary was over three hundred years old at that time, it seems of interest to ask who made the change, and why they made it. -

Wildflowers of County Roscommon Yelly Flag Meadow Sweet Dandelion Seed Head Birdsfoot Trefoil Water Avens

Wildflowers of County Roscommon Yelly Flag Meadow Sweet Dandelion Seed Head Birdsfoot Trefoil Water Avens Here are some special places in County Wildflowers of Wildflowers of Roscommon special interest in to see the best County Roscommon County Roscommon The Pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea) wildflowers... is a bogland plant native to North America Ox-eye Daisy but was introduced into Ireland in the early Annaghmore Lough 1900s and planted in a few midland bogs. Primrose Annaghmore Lough The plant is carnivorous. The leaf is pitcher near Strokestown shaped and holds water. Insects fall into the water and the plant absorbs nutrients from Bogs throughout the county the dead insects. Hedgerows everywhere This tall plant grows in one bog near the river Shannon in northeast Roscommon. Lake O’Flynn near Ballinlough Lough Allen shore Pitcher Plant Lough Funshinagh Lough Ree shore Mote Park Wood and bog Lough Key Forest Park Protected St John’s Wood Wildflowers A number of wild plants are protected Suck Valley under the Flora Protection Order 1999. In County Roscommon two protected wildflower species grow; Mudwort (Limosella aquatica) and Irish Lady’s Tresses (Spiranthes romanzoffiana). Both species have been recorded near Lough Allen in North Roscommon. Irish Lady’s Tresses Produced by Roscommon County Council © 2009 Text and images: John J Earley MSc. © 2009 Funded by the Heritage Council. Wildflowers of County Roscommon Wild orchids County Spring Wildflowers In early Spring with the lengthening days and warmer weather the first signs of new in Roscommon Roscommon season plant growth begin to appear. Generally the catkins appear on the Hazel tree around the first week of February. -

Ulster Final Programme

CLUICHE CEANNAIS ULADH2O2O AN CABHÁN DÚN NAVERSUS NGALL 22Ú SAMHAIN 2020 IT’S ON PÁIRC LÚTHCHLEASÍOCHTA ARD MHACHA 4:00PM £5/€5 RÚNAI: ULSTER.GAA.IE The stands may be silent but TODAY’S GAME we know our communities are CLUICHE AN LAE INNIU standing tall behind us. Help us make your SuperFan voice heard by sharing a video of how you Support Where You’re From on: @supervalu_irl @SuperValuIreland using the #SuperValuSuperFans SUPPORT 72 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O Where You’re From TODAY’S GAME CLUICHE AN LAE INNIU (SUBJECT TO WINNER ON THE DAY) @ ATHLETICVERSUS GROUNDS, ARMAGH SUNDAY 22ND NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Final (4:00pm) Réiteoir: Barry Cassidy (Doire) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Ciaran Branagan (An Dún) Maor Líne: Jerome Henry (Maigh Eo) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Sean Laverty (Aontroim) Maoir: Kevin Toner, Alan Nash, Tom O’Kane & Marty Donnelly CLÁR AN LAE: IF GAME GOES TO EXTRA TIME 15.20 Teamsheets given to Match Referee 1 7. 4 4 Toss & updated Teamsheets to Referee 15.38 An Cabhán amach ar an pháirc 17.45 Start of Extra Time 1st Half 15.41 Dún na nGall amach ar an pháirc 17.56* End of Extra Time 1st Half 15.45 Oifigigh an Chluiche amach ar an pháirc Teams Remain on the Pitch 15.52 Toss 17.58* Start of Extra Time 2nd Half 15.57 A Moment’s Silence 18.00* End of Extra Time 2nd Half 15.58 Amhrán na bhFiann 16.00 Tús an chluiche A water break will take place between IF STILL LEVEL, PHASE 2 (PENALTIES) the 15th & 20th minute of the half** 18:05 Players registered with the 16.38* Leath-am Referee & Toss An Cabhán to leave the field 18:07 Penalties immediately on half time whistle Dún na nGall to leave the field once An Cabhán have cleared the field 16.53* An dara leath A water break will take place between the 15th & 20th minute of the half** 17.35* Críoch an chluiche 38 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD FOCAL ÓN UACHTARÁN Fearadh na fáilte romhaibh chuig Craobhchomórtas programme. -

Ireland's Heritage of Geographical Names

Wiener Schriften zur Geographie und Kartographie, Vol. 18, Wien 2009, pp. 79–85 79 MAC GIOLLA EASPAI G , Dónall (Dublin/Baile Átha Cliath, Ireland)* Ireland’s heritage of geographical names Contents Summary 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................79 2 The historical corpus of Ireland’s place names .......................................................................................80 3 Non-Irish influence on place names ........................................................................................................81 4 The anglicisation of Ireland’s place names ..............................................................................................82 5 The restoration of Irish place-name forms ..............................................................................................82 6 The work of the Place Names Branch .....................................................................................................82 7 Place Names Database of Ireland ..........................................................................................................83 8 References .............................................................................................................................................84 Summary Geographical names have been central to Irish tradition from the dawn of history. The medieval Irish created a separate literary genre, the Dindshenchas, meaning ‘the lore of notable -

Neven Maguire (RTE Guide – December 2009) Neven Maguire's

Neven Maguire (RTE Guide – December 2009) Neven Maguire's Home Chef starts on RTÉ One on January 7 Neven Maguire is not what you'd expect from a celebrity chef. Polite, personable and without a bad word for anyone, the 37-year-old Cavan man seems almost too good to be a true blue kitchen devil. But he is the real deal, not only a great cook but a genuinely nice guy. "With me what you see is what you get," he says as if at loss as to how else he might describe himself. And if that phrase is hackneyed, it fits Maguire perfectly, a chef whose award-winning restaurant has put Blacklion on the culinary map and made a star of its unassuming yet ambitious proprietor. "I don't want to be the best there is," he says. "I want to be the best that I can be." Blacklion is a quiet country village on the northern edge of County Cavan. Neven Maguire was born and reared here in a three storey building that was once an old Garda station and is now McNean House and Restaurant. Voted Food and Wine magazine's Restaurant of the Year 2008, it is a homely establishment with Neven's wife, Amelda, working front of house. The couple live a few miles outside the village in a stylish single-storey dwelling in which Maguire's last TV series (Food From The Sun )and his latest, Neven Maguire's Home Chef, was filmed. This series ties in with his seventh, and latest, cookbook of the same name: a user-friendly guide with recipes tried and tested in his restaurant where the local is treasured. -

The Irish Standard. (Minneapolis, Minn. ; St. Paul

I ^-,=? * *• i . 1 I ,l *p ^,-" 4" l' ~ v Tf^ ' ^ v *WY- , "7 s ^ * THE IRISH STANDARD Saturday, May 6, 1916. French make) and a large pike and MEATH. mel decided to promote a testimonial President of Insurance Fund—T. J. ST. LOUIS COUNTY. crook' slashers, with hickory handle St. Patrick's Pay was Gaelic League Doyle, St. Paul. to M. J. Casey, who is retiring from Secretary of Insurance — Thomas County President John Simons, 511 was made near the premises. The Flag Day in Navan and a satisfactory the managership of the local branch Welch, Stillwater. N. 13th Ave. E., Duluth, Minn. Stale Treasurer of Insurance—John i illes were of the olden type and were sum was realized. The following col of the National bank, after 52 years' Sheeliy, Montgomery. Division No. l, Duiuth—President covered with rust. lected: P. Conroy, W. J. and J. Ken service. State Medical Director—Dr. J. V. William F. Murnlan, 509 E. 3rd St; r News from Ireland O'Connor, St. Paul. Vice Pres., John F. Scanlon, 107 ft W. The death took place on the 14th nedy; J. Reillv and B. Reilly, P. and An extensive range of buildings Director of Insurance Fund — John 5th St.; Fin. and Ins. Sec., W. J. Mc- Moran, Minneapolis; K J. McManua, St Bride, 7 W. 5th St.; Rec. Sec., W. J. ij'st. of an old and respected citizen B. Clarke. The usual annual collec used by Messrs. John O'Donnell & Co. Paul; P. L,. Cummings, Minneapolis; J. Lynott, 1224 E. 3d St.; Treas., J. -

Roscommon County Development Plan 2014–2020 I

ROSCOMMON COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2014 - 2020 ELPHIN AREA PLAN VARIATION NO. 1 th EFFECTIVE DATE 24 JULY 2017 Variation No. 1 of the Elphin Area Plan 2014-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. OVERVIEW 1 2. CONTEXT AND PROFILE OF ELPHIN 1 2.1 LOCATION 1 2.2 RECENT DEVELOPMENT TRENDS 1 2.3 DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVE 1 2.4 STRATEGIC AIMS OF THE ELPHIN LOCAL AREA PLAN 2 2.5 GENERAL PLANNING POLICIES IN RELATION TO DEVELOPMENT (OF ALL CATEGORIES) FOR ELPHIN 3 3. BUILT, ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE 4 3.1 ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATION AREA 4 3.2 ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE 5 3.3 NATURAL HERITAGE 5 3.4 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT 5 3.5 POLICIES IN RELATION TO BUILT, ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE 5 3.6 OBJECTIVES IN RELATION TO BUILT, ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE 6 4. TRANSPORT AND PARKING 7 4.1 PLANNING POLICY IN RELATION TO TRANSPORT AND PARKING 7 4.2 OBJECTIVES IN RELATION TO TRANSPORT AND PARKING 8 5. DEVELOPMENT OF CORE TOWN CENTRE AND PERIPHERAL TOWN CENTRE 9 5.1 BROWN FIELD AND BACKLAND SITES 9 5.2 VACANT PREMISES 10 5.3 PLANNING POLICIES IN RELATION TO THE CORE TOWN CENTRE AND PERIPHERAL TOWN 10 5.4 OBJECTIVES IN RELATION TO THE CORE TOWN CENTRE AND PERIPHERAL TOWN 10 6. RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT 11 6.1 PLANNING POLICIES IN RELATION TO RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT 13 6.2 OBJECTIVES IN RELATION TO RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT 13 7. ECONOMIC INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT 14 7.1 PLANNING POLICIES IN RELATION TO ECONOMIC, INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT 14 7.2 OBJECTIVES IN RELATION TO ECONOMIC, INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT 14 Variation No. -

COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 1

JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY CAVAN JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 2 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY CAVAN JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 3 Foreword The Architectural Inventory of County The NIAH survey of the architectural Cavan was carried out in 2012. A total of 860 heritage of County Cavan can be accessed structures were recorded. Of these some 770 on the internet at: are deemed worthy of protection. www.buildingsofireland.ie The Inventory should not be regarded as exhaustive as, over time, other buildings and structures of merit may come to light. The purpose of the Inventory and of this NATIONAL INVENTORY of ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE Introduction is to explore the social and historical context of the buildings and to facilitate a greater appreciation of the built heritage of County Cavan. 3 JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 4 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY CAVAN CUILCAGH LANDSCAPE In contrast to the predominant drumlin landscape of Cavan, wilder, exposed landscapes characterise the long and narrow western portion of the county, with great expanses of blanket upland bogs contrasted against the prominent outline of Cuilcagh, part of the Cuilcagh Mountain range shared with county Fermanagh. JD110 NIAH CAVAN BOOK(AW)(2)_COUNTY CAVAN 25/07/2013 16:56 Page 5 Introduction Cavan is the most southerly county of uplands lies the cradle of the Shannon, a deep Ulster. -

1 Table 1: Place of Work of County Roscommon Residents, 2011 and 2016 in 2016, 25,488 Residents of County Roscommon Were in Empl

Table 1: Place of Work of County Roscommon Residents, 2011 and 2016 Roscommon 2011 2016 Place of work - all locations 24,064 25,488 Roscommon 10,778 10,993 Westmeath 3,092 3,219 Leitrim 1,164 1,084 Longford 910 988 Galway County 908 920 Mayo 503 674 Sligo 612 619 Dublin City 309 375 Galway City 272 361 Offaly 225 255 Fingal 81 109 South Dublin 80 107 Kildare 58 107 Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown 55 72 Cavan 26 42 Meath 42 38 Limerick 17 35 Tipperary 14 30 Cork County 19 17 Cork City 8 15 Donegal 21 14 Wicklow 9 13 Laois 15 12 Kerry 8 11 Antrim 6 10 Clare 8 9 Louth 7 9 Fermanagh 10 8 Kilkenny 11 7 Carlow 5 7 Monaghan 6 6 Waterford 3 5 Wexford 3 4 Down 0 4 Derry 1 3 Armagh 1 1 Tyrone 1 1 Place of work - overseas 24 28 No fixed place of work 2,458 2,678 Place of work - not stated 2,294 2,598 Source CSO Census 2016 Profile 6 - Commuting in Ireland / E6045 / In 2016, 25,488 residents of County Roscommon were in employment (Table 1). Of these 10,993 worked in County Roscommon with County Westmeath the next most popular location (3,219), followed by County Leitrim (1,084) and County Longford (988). A total of 2,678 had no fixed place of work, while 2,598 did not state their work location. 1 Table 2: Place of Residence of Workers working in County Roscommon, 2011 and 2016 Roscommon 2011 2016 Place of Residence- all locations 14,422 14,840 Roscommon 10,778 10,993 Galway County 989 1,034 Westmeath 635 692 Leitrim 403 491 Sligo 396 417 Mayo 435 405 Longford 381 386 Offaly 131 161 Galway City 43 37 Cavan 32 35 Tipperary 19 28 Kildare 22 27 Laois 13 21 Dublin City 18 19 Donegal 8 15 Meath 10 13 Fingal 21 11 Cork County 19 9 South Dublin 16 9 Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown 9 8 Limerick City and County 8 8 Clare 3 7 Kerry 6 3 Carlow 1 3 Kilkenny 5 2 Monaghan 3 2 Waterford City and County 3 2 Wicklow 5 1 Cork City 4 1 Wexford 4 0 Louth 2 0 Source CSO Census 2016 Profile 6 - Commuting in Ireland / E6045 / In 2016, there were 14,840 people whose place of work was located in County Roscommon (Table 2). -

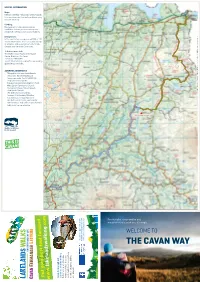

The Cavan Way

USEFUL INFORMATION Maps: Relevant OSI Map – Discovery Series Map 26. It is recommended that walkers always carry relevant OSI map. Clothing: Be prepared for changeable weather conditions. Ensure you have waterproof/ windproof clothing as well as sturdy boots. Emergencies: In the event of an emergency call 999 or 112. Tourist Information: There are a wide variety of activities and attractions on offer in the Geopark and the wider Cavan area. To find out more visit; The Market House Tourist Information Centre, Blacklion, Co. Cavan. T: (+353) 719853941 Tourist Information/Tea & Coffee and walking guides/maps available. Cavan Burren Park ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • This publication was funded under the project Harnessing Natural Resources under the INTERREG IVA Programme through the European Regional Development Fund. • West Cavan Community Council. • Marble Arch Caves Global Geopark. • Irish Sports Council. © Ordnance Survey Ireland, Licence No. 2014/01/CCMA/CavanCountyCouncil • The Ordnance Survey Office. • Seamus O’ hUltacháin, Blacklion. • A special word of appreciation is due to the local farming community without whose help and co-operation this walk would not be available. The Shannon Pot Forest walks, road rambles and megalithic trails await you, it’s magic.. WELCOME TO This project is supported by the EU’s the by supported is project This managed Programme, IVA INTERREG Body Programmes EU Special by the THE CAVAN WAY .com lakelandswalking ww. Put your best foot forward forward foot best your Put Cavan, Fermanagh and Fermanagh Cavan, walking. for ideal are Leitrim terrains, of array vast a With and forest lakes, mountains, something is there walks castle abilities strengths, all suit to interests. -

0262 Cavan County Council

Submission by Cavan County Council National Planning Framework Consultation legend Dublin. <;""v,,"~nid,"" :N3IM3f D"hl •••• B"o.If;oo;ICllnirinrcM1J ~ March 2017 Chief Executive J_ Cathaoirleach go-::- Do/ '--< Introduction Cavan County Council welcomes the publication of the consultation documents from the National Planning Framework and the opportunity to make a submission. Having considered the consultation documents, Cavan County Council highlight the following key strategic aspects to be considered as part of the National Planning Framework preparation. Role within Region There are a number of different functional areas within the Northern and Western Region. It is important that the National Panning Framework recognises such functional areas and the unique role that each functional area plays within the wider economy. The Cavan/Monaghan sub-region is one such function area. Each functional area needs to have a designation primary urban centre and Cavan Town is positioned to act as the principal town in this regard in terms of housing, job and education delivery. In addition to being the largest population centre in the region by a notable distance, it contains strategic facilities such as a hospital, Cavan Institute, Agricultural College, Cathedral and Sports Stadium, essential for sustainable growth. Cavan's strategic significance in further evident as within a GO-minute drive, a total population of approximately 1.3 million is within its catchment with an active workforce exceeding SOO,OOOpersons. Economic Growth There is opportunity to build on traditional sectors of the economy in Cavan such as agribusiness, food and engineering to assist in the future economic success of the Region.