Murphy Gold Rush Dog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography of Education, 1911-11

I UNITEDSTATESBUREAU ,OFEDUCATION 657 BULLETIN, 1915, NO. 30 - - - WHOLE NUMBER BIBLIOGRAPHYOFEDUCATION FOR 19,1 1-1 2 a at, Ab. WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTINGOFFICE 1915 ADDITIONAL COPIES PIMLICATION MAT DR PROCUREDFROM THE '1:PERIN-TENDERT OrDOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OPTICS WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 2O CENTS PER COPY 205570 .A AUG 28 1918 athl 3 a -3g CONTENTS. i9IS 30 -3 8 Generalities: Bibliography Page. New periodicals 7 9 Pulaications of associations, sociefies, conferences,etc. National State and local 9 14(i' Foreign 23 International Documents 23 Encyclopedias 23 24 History and description: General Ancient 24 25 Medieval 25 odena 25 United States . Ge.neral 25 Public-school system 28 Secondary education 28 Higher or university education 29 National education association 30 Canada s 30 South AmericaWest Indies 31 Great Britain 31 Secondary education 32 Higher or university education 32 Austria 32 France 33 Germany 33 Higher or university education 34 Italy Belgium 35 Denmark 35 Sweden 35 Iceland 35 Switzerland 35 Asia 35 .China 35 India Japan 38 Now Zealand 38 Philippine Islands 38' Biography 37 Theory of education 38 Principles and practice of teaching: General 42 Special methods of instruction 44 Moving pictures, phonographs, etc 44 Methods of study.. 45 Educational psychology 45 Child study 48 Child psychology 49 Plays, games, etc 49 4 CONTENTS. Principles and practice of teachingContinued. Pais. Kindergarten and primary education 50 Montessori method 52 Elementary or common-school education 54 Rural schools. 54 Curriculum. 57 Reading . 58 Penmanship 58 . Spelling 58 Composition and language study 59 Languages 59 History 59 Geography 59 Nature study and science 60 Arithmetic . -

Download Operation Cookout Indictment.Pdf

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TJ EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA ^ I 4 2019 Newport News Division I U.S. L/lislHiCTCO/inT L NEWPORT VA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA UNDER SEAL V. Criminal No. 4:19-cr-47 RAMIRO RAMIREZ-BARRETO, 21 U.S.C. § 846 a/k/a "Edward Lee Tijema" Conspiracy to Distribute and Possess with Intent to a/k/a "Ramon Ramirez Tapia" Distribute Cocaine, Heroin, Cocaine Base, and a/k/a "Morelos" Fentanyl (Counts 1-2, 25, 29-33, 76-78, 80-82, 84- (Count 1) 104,106) 18 U.S.C. § 1956(h) IBAN BARRETO HERNANDEZ, Conspiracy to Launder Money a/k/a "Ivan Barreto" (Count 2) (Counts 1-2, 87, 89) 21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1) and (b)(l)(B)(ii) MADAI RAMIREZ-BARRETO, Distribution and Possession with Intent to (Counts 2, 90) Distribute of 500 Grams or More of Cocaine (Counts 3, 7-8, 11-14, 18,30) JUAN CARLOS CERVANTES, a/k/a "Juan Carlos Cervantes Ramirez" 21 U.S.C. §§ 841(a)(1) and (b)(1)(C) a/k/a "Nenuco" Distribution and Possession with Intent to (Counts 1,29-30, 94-95) Distribute Heroin (Counts 4-6, 10, 17) CAMILIO GONZALEZ, (Counts 1, 82-83) 21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1) and (b)(1)(C) Possession with Intent to Distribute Cocaine Base JENNIFER LYNN BING, (Count 9) a/k/a "Jenny" (Counts 54, 60) 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1) and 924(a)(2) Felon in Possession of a Firearm KEITH ANTONIA BROWNSON, (Count 15) a/k/a "Ken" (Counts 1, 2, 92-93, 97-99, 102-104) 21 U.S.C. -

Aftermath : Seven Secrets of Wealth Preservation in the Coming Chaos / James Rickards

ALSO BY JAMES RICKARDS Currency Wars The Death of Money The New Case for Gold The Road to Ruin Portfolio/Penguin An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2019 by James Rickards Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rickards, James, author. Title: Aftermath : seven secrets of wealth preservation in the coming chaos / James Rickards. Description: New York : Portfolio/Penguin, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019010409 (print) | LCCN 2019012464 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735216969 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735216952 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Investments. | Financial crises. | Finance—Forecasting. | Economic forecasting. Classification: LCC HG4521 (ebook) | LCC HG4521 .R5154 2019 (print) | DDC 332.024—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019010409 Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone. While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Europe the Way IT Once Was (And Still Is in Slovenia) a Tour Through Jerry Dunn’S New Favorite European Country Y (Story Begins on Page 37)

The BEST things in life are FREE Mineards’ Miscellany 27 Sep – 4 Oct 2012 Vol 18 Issue 39 Forbes’ list of 400 richest people in America replete with bevy of Montecito B’s; Salman Rushdie drops by the Lieffs, p. 6 The Voice of the Village S SINCE 1995 S THIS WEEK IN MONTECITO, P. 10 • CALENDAR OF EVENTS, P. 44 • MONTECITO EATERIES, P. 48 EuropE ThE Way IT oncE Was (and sTIll Is In slovEnIa) A tour through Jerry Dunn’s new favorite European country y (story begins on page 37) Let the Election Begin Village Beat No Business Like Show Business Endorsements pile up as November 6 nears; Montecito Fire Protection District candidate Jessica Hambright launches Santa Barbara our first: Abel Maldonado, p. 5 forum draws big crowd, p. 12 School for Performing Arts, p. 23 A MODERNIST COUNTRY RETREAT Ofered at $5,995,000 An architecturally significant Modernist-style country retreat on approximately 6.34 acres with ocean and mountain views, impeccably restored or rebuilt. The home features a beautiful living room, dining area, office, gourmet kitchen, a stunning master wing plus 3 family bedrooms and a 5th possible bedroom/gym/office in main house, and a 2-bedroom guest house, sprawling gardens, orchards, olives and Oaks. 22 Ocean Views Private Estate with Pool, Clay Court, Guest House, and Montecito Valley Views Offered at $6,950,000 DRE#00878065 BEACHFRONT ESTATES | OCEAN AND MOUNTAIN VIEW RETREATS | GARDEN COTTAGES ARCHITECT DESIGNED MASTERPIECES | DRAMATIC EUROPEAN STYLE VILLAS For additional information on these listings, and to search all currently available properties, please visit SUSAN BURNS www.susanburns.com 805.886.8822 Grand Italianate View Estate Offered at $19,500,000 Architect Designed for Views Offered at $10,500,000 33 1928 Santa Barbara Landmark French Villa Unbelievable city, yacht harbor & channel island views rom this updated 9,000+ sq. -

Glenn Mitchell the TRUE FAREWELL of the TRAMP

Glenn Mitchell THE TRUE FAREWELL OF THE TRAMP Good afternoon. I’d like to begin with an ending ... which we might call `the Tramp’s First Farewell’. CLIP: FINAL SCENE OF `THE TRAMP’ That, of course, was the finale to Chaplin’s 1915 short film THE TRAMP. Among Chaplin scholars – and I think there may be one or two here today! - one of the topics that often divides opinion is that concerning the first and last appearances of Chaplin’s Tramp character. It seems fair to suggest that Chaplin’s assembly of the costume for MABEL’S STRANGE PREDICAMENT marks his first appearance, even though he has money to dispose of and is therefore technically not a tramp. KID AUTO RACES AT VENICE, shot during its production, narrowly beat the film into release. Altogether more difficult is to pinpoint where Chaplin’s Tramp character appears for the last time. For many years, the general view was that the Tramp made his farewell at the end of MODERN TIMES. As everyone here will know, it was a revision of that famous conclusion to THE TRAMP, which we saw just now ... only this time he walks into the distance not alone, but with a female companion, one who’s as resourceful, and almost as resilient, as he is. CLIP: END OF `MODERN TIMES’ When I was a young collector starting out, one of the key studies of Chaplin’s work was The Films of Charlie Chaplin, published in 1965. Its authors, Gerald D. McDonald, Michael Conway and Mark Ricci said this of the end of MODERN TIMES: - No one realized it at the time, but in that moment of hopefulness we were seeing Charlie the Little Tramp for the last time. -

Riley Thorn and the Dead Guy Next Door

RILEY THORN AND THE DEAD GUY NEXT DOOR LUCY SCORE Copyright © 2020 Lucy Score All rights reserved No Part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electric or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without prior written permission from the publisher. The book is a work of fiction. The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author. ISBN: 978-1-945631-67-2 (ebook) ISBN: 978-1-945631-68-9 (paperback) lucyscore.com 082320 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Chapter 29 Chapter 30 Chapter 31 Chapter 32 Chapter 33 Chapter 34 Chapter 35 Chapter 36 Chapter 37 Chapter 38 Chapter 39 Chapter 40 Chapter 41 Chapter 42 Chapter 43 Chapter 44 Chapter 45 Chapter 46 Chapter 47 Chapter 48 Chapter 49 Chapter 50 Chapter 51 Chapter 52 Chapter 53 Chapter 54 Chapter 55 Chapter 56 Chapter 57 Chapter 58 Chapter 59 Chapter 60 Epilogue Author’s Note to the Reader WONDERING WHAT TO READ NEXT?: About the Author Acknowledgments Lucy’s Titles To Josie, a real life badass. 1 10:02 p.m., Saturday, July 4 he dead talked to Riley Thorn in her dreams. -

The Inside Story of the Gold Rush, by Jacques Antoine Moerenhout

The inside story of the gold rush, by Jacques Antoine Moerenhout ... translated and edited from documents in the French archives by Abraham P. Nasatir, in collaboration with George Ezra Dane who wrote the introduction and conclusion Jacques Antoine Moerenhout (From a miniature in oils on ivory, possibly a self-portrait; lent by Mrs. J.A. Rickman, his great-granddaughter.) THE INSIDE STORYTHE GOLD RUSH By JACQUES ANTOINE MOERENHOUT Consul of France at Monterey TRANSLATED AND EDITED FROM DOCUMENTS IN THE FRENCH ARCHIVES BY ABRAHAM P. NASATIR IN COLLABORATION WITH GEORGE EZRA DANE WHO WROTE THE INTRODUCTION AND CONCLUSION SPECIAL PUBLICATION NUMBER EIGHT CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY The inside story of the gold rush, by Jacques Antoine Moerenhout ... translated and edited from documents in the French archives by Abraham P. Nasatir, in collaboration with George Ezra Dane who wrote the introduction and conclusion http://www.loc.gov/resource/ calbk.018 SAN FRANCISCO 1935 Copyright 1935 by California Historical Society Printed by Lawton R. Kennedy, San Francisco I PREFACE THE PUBLICATION COMMlTTEE of the California Historical Society in reprinting that part of the correspondence of Jacques Antoine Moerenhout, which has to do with the conditions in California following the discovery of gold by James Wilson Marshall at Sutter's sawmill at Coloma, January 24, 1848, under the title of “The Inside Story of the Gold Rush,” wishes to acknowledge its debt to Professor Abraham P. Nasatir whose exhaustive researches among French archives brought this hitherto unpublished material to light, and to Mr. George Ezra Dane who labored long and faithfully in preparing it for publication. -

Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn : the Zen Records of Hakuin Ekaku / Hakuin Zenji ; Translated by Norman Waddell

The Publisher is grateful for the support provided by Rolex Japan Ltd to underwrite this edition. And our thanks to Bruce R. Bailey, a great friend to this project. Copyright © 2017 by Norman Waddell All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. ISBN: 978-1-61902-931-6 THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Names: Hakuin, 1686–1769, author. Title: Complete poison blossoms from a thicket of thorn : the zen records of Hakuin Ekaku / Hakuin Zenji ; translated by Norman Waddell. Other titles: Keisåo dokuzui. English Description: Berkeley, CA : Counterpoint Press, [2017] Identifiers: LCCN 2017007544 | ISBN 9781619029316 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Zen Buddhism—Early works to 1800. Classification: LCC BQ9399.E594 K4513 2017 | DDC 294.3/927—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007544 Jacket designed by Kelly Winton Book composition by VJB/Scribe COUNTERPOINT 2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318 Berkeley, CA 94710 www.counterpointpress.com Printed in the United States of America Distributed by Publishers Group West 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the Memory of R. H. Blyth CONTENTS Chronology of Hakuin’s Life Introduction BOOK ONE Instructions to the Assembly (Jishū) BOOK TWO Instructions to the Assembly (Jishū) (continued) General Discourses (Fusetsu) Verse Comments on Old Koans (Juko) Examining Old -

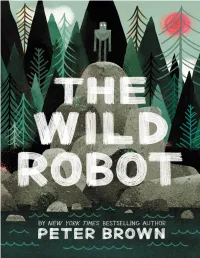

The Wild Robot.Pdf

Begin Reading Table of Contents Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. To the robots of the future CHAPTER 1 THE OCEAN Our story begins on the ocean, with wind and rain and thunder and lightning and waves. A hurricane roared and raged through the night. And in the middle of the chaos, a cargo ship was sinking down down down to the ocean floor. The ship left hundreds of crates floating on the surface. But as the hurricane thrashed and swirled and knocked them around, the crates also began sinking into the depths. One after another, they were swallowed up by the waves, until only five crates remained. By morning the hurricane was gone. There were no clouds, no ships, no land in sight. There was only calm water and clear skies and those five crates lazily bobbing along an ocean current. Days passed. And then a smudge of green appeared on the horizon. As the crates drifted closer, the soft green shapes slowly sharpened into the hard edges of a wild, rocky island. The first crate rode to shore on a tumbling, rumbling wave and then crashed against the rocks with such force that the whole thing burst apart. -

Hands Up! by Steve Massa

Hands Up! By Steve Massa Raymond Griffith is one of silent come- dy’s unjustly forgotten masters, whose onscreen persona was that of a calm, cool, world-weary bon vivant – some- thing like Max Linder on Prozac. After a childhood spent on stage touring in stock companies and melodramas, he ended up in films at Vitagraph in 1914 and went on to stints at Sennett,- L Ko, and Fox as a comedy juvenile. Not mak- ing much of an impression due to a lack of a distinctive character, he went be- hind the camera to become a gagman, working at Sennett and for other comics like Douglas MacLean. In 1922 he re- turned to acting and became the ele- gant, unflappable ladies’ man. Stealing comedies such as “Changing Husbands,” “Open All Night,” and “Miss Bluebeard” (all 1924) away ing very popular with his character of “Ambrose,” a put- their respective stars Paramount decided to give him his upon everyman with dark-circled eyes and a brush mous- own series, and he smarmed his way through ten starring tache. Leaving Sennett in 1917 he continued playing Am- features starting with “The Night Club” (1925). brose for L-Ko, Fox, and the independent Poppy Come- dies and Perry Comedies. His career stalled in the early “Hands Up!” (1926) soon followed, and is the perfect 1920s when he was blacklisted by an influential produc- showcase for Griffith’s deft comic touch and sly sense of er, but his old screen mate Charlie Chaplin came to the the absurd. The expert direction is by Clarence Badger, rescue and made Mack part of his stock company in films who started in the teens with shorts for Joker and Sen- such as “The Idle Class” (1921) and “The Pilgrim” (1923). -

Recent Publications on the History of Mining

Recent Publications on the History of Mining Compiled by Lysa Wegman-French The following bibliography contains books, Includes Arizona copper mines, the Colorado dissertations and theses, articles and chapters of Coal Wars, and communist miners involved in books, and other media—organized within those the Cold War civil rights struggle.] four categories—that provide new content relat- ed to the history of all types of mining in North Allan, Chris. Arctic Odyssey: A History of America (that is, Canada, the United States, and the Koyukuk River Gold Stampede in Alaska’s Far Central America). It does not include book re- North. Fairbanks: National Park Service, Fair- view articles, nor reissued or subsequent editions banks Administrative Center, 2016. of material. Digital capabilities are changing our options for Ammons, Doug. A Darkness Lit by Heroes: seeing works of interest. Some films and printed The [Butte] Granite Mountain-Speculator Mine works are available for viewing on the internet. Disaster of 1917. Missoula: Water Nymph Press, We have not included URLs for these, but check 2017. the internet for their availability. Moreover, some articles are available only on the internet; for these Andrist, Ralph K. The Gold Rush. [Scotts we have included the URL. In addition, many old- Valley, CA]: CreateSpace Independent Publish- er books are now being reissued as e-books, and ing, 2016. [Also an e-book.] older films are being distributed as DVDs. We did not include them in this compilation since the Anschutz, Philip F. Out Where the West Be- content is not new. However, if you are interested gins: Profiles, Visions, and Strategies of Early West- in an older work, check to see if it is now available ern Business Leaders.