1 Resituating Gender and Violence During the Great War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi's View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious

religions Article Gandhi’s View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious Theology Ephraim Meir 1,2 1 Department of Jewish Philosophy, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel; [email protected] 2 Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), Wallenberg Research Centre at Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa Abstract: This article describes Gandhi’s view on Judaism and Zionism and places it in the framework of an interreligious theology. In such a theology, the notion of “trans-difference” appreciates the differences between cultures and religions with the aim of building bridges between them. It is argued that Gandhi’s understanding of Judaism was limited, mainly because he looked at Judaism through Christian lenses. He reduced Judaism to a religion without considering its peoplehood dimension. This reduction, together with his political endeavors in favor of the Hindu–Muslim unity and with his advice of satyagraha to the Jews in the 1930s determined his view on Zionism. Notwithstanding Gandhi’s problematic views on Judaism and Zionism, his satyagraha opens a wide-open window to possibilities and challenges in the Near East. In the spirit of an interreligious theology, bridges are built between Gandhi’s satyagraha and Jewish transformational dialogical thinking. Keywords: Gandhi; interreligious theology; Judaism; Zionism; satyagraha satyagraha This article situates Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s in the perspective of a Jewish dialogical philosophy and theology. I focus upon the question to what extent Citation: Meir, Ephraim. 2021. Gandhi’s religious outlook and satyagraha, initiated during his period in South Africa, con- Gandhi’s View on Judaism and tribute to intercultural and interreligious understanding and communication. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

Chapter 7. Remembering Them

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2017-02 Understanding Atrocities: Remembering, Representing and Teaching Genocide Murray, Scott W. University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51806 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNDERSTANDING ATROCITIES: REMEMBERING, REPRESENTING, AND TEACHING GENOCIDE Edited by Scott W. Murray ISBN 978-1-55238-886-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Red Sand: Canadians in Persia & Transcaucasia, 1918 Tom

RED SAND: CANADIANS IN PERSIA & TRANSCAUCASIA, 1918 TOM SUTTON, MA THESIS ROUGH DRAFT, 20 JANUARY 2012 CONTENTS Introduction Chapter 1 Stopgap 2 Volunteers 3 The Mad Dash 4 Orphans 5 Relief 6 The Push 7 Bijar 8 Baku 9 Evacuation 10 Historiography Conclusion Introduction NOTES IN BOLD ARE EITHER TOPICS LEFT UNFINISHED OR GENERAL TOPIC/THESIS SENTENCES. REFERECNCE MAP IS ON LAST PAGE. Goals, Scope, Thesis Brief assessment of literature on Canada in the Russian Civil War. Brief assessment of literature on Canadians in Dunsterforce. 1 Stopgap: British Imperial Intentions and Policy in the Caucasus & Persia Before 1917, the Eastern Front was held almost entirely by the Russian Imperial Army. From the Baltic to the Black Sea, through the western Caucasus and south to the Persian Gulf, the Russians bolstered themselves against the Central Empires. The Russians and Turks traded Kurdistan, Assyria, and western Persia back and forth until the spring of 1917, when the British captured Baghdad, buttressing the south-eastern front. Meanwhile, the Russian army withered in unrest and desertion. Russian troops migrated north through Tabriz, Batum, Tiflis, and Baku, leaving dwindling numbers to defend an increasingly tenable front, and as the year wore on the fighting spirit of the Russian army evaporated. In the autumn of 1917, the three primary nationalities of the Caucasus – Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis – called an emergency meeting in Tiflis in reaction to the Bolshevik coup d'etat in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. In attendance were representatives from trade unions, civil employees, regional soviets, political parties, the army, and lastly Entente military agents. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

1. Satyagraha in South Africa1

1. SATYAGRAHA IN SOUTH AFRICA1 FOREWORD Shri Valji Desai’s translation has been revised by me, and I can assure the reader that the spirit of the original in Gujarati has been very faithfuly kept by the translator. The original chapters were all written by me from memory. They were written partly in the Yeravda jail and partly outside after my premature release. As the translator knew of this fact, he made a diligent study of the file of Indian Opinion and wherever he discovered slips of memory, he has not hesitated to make the necessary corrections. The reader will share my pleasure that in no relevant or material paricular has there been any slip. I need hardly mention that those who are following the weekly chapters of My Experiments with Truth cannot afford to miss these chapters on satyagraha, if they would follow in all its detail the working out of the search after Truth. M. K. GANDHI SABARMATI 26th April, 19282 1 Gandhiji started writing in Gujarati the historty of Satyagraha in South Africa on November 26, 1923, when he was in the Yeravda Central Jail; vide “Jail Diary, 1923.” By the time he was released, on February 5, 1924, he had completed 30 chapters. The chapters of Dakshina Africana Satyagrahano Itihas, as it was entitled, appeared serially in the issues of the Navajivan, beginning on April 13, 1924, and ending on November 22, 1925. The preface to the first part was written at Juhu, Bombay, on April 2, 1924; that to the second appeared in Navajivan, 5-7-1925. -

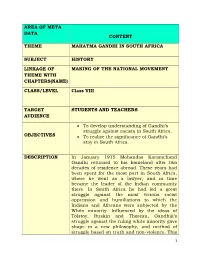

Area of Meta Data Content Theme Mahatma Gandhi In

AREA OF META DATA CONTENT THEME MAHATMA GANDHI IN SOUTH AFRICA SUBJECT HISTORY LINKAGE OF MAKING OF THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT THEME WITH CHAPTERS(NAME) CLASS/LEVEL Class VIII TARGET STUDENTS AND TEACHERS AUDIENCE To develop understanding of Gandhi’s struggle against racism in South Africa. OBJECTIVES To realize the significance of Gandhi’s stay in South Africa. DESCRIPTION In January 1915 Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned to his homeland after two decades of residence abroad. These years had been spent for the most part in South Africa, where he went as a lawyer, and in time became the leader of the Indian community there. In South Africa he had led a great struggle against the most vicious racist oppression and humiliations to which the Indians and Africans were subjected by the White minority. Influenced by the ideas of Tolstoy, Ruskin and Thoreau, Gandhiji’s struggle against the ruling white minority gave shape to a new philosophy, and method of struggle based on truth and non-violence. This 1 was Passive Resistance, or Satyagraha. It also meant mass actions through hartals, marches, mass violation of oppressive laws and mass courting of arrests. The challenges and trials that Gandhi underwent in Africa in the form of racist oppression was very significant. It gave birth to new ideas and philosophy, and method of struggle based on truth and non- violence. KEY WORDS Gandhi, Durban Court House, Tolstoy farm,, Pietermaritzburg Station, Satyagraha, Natal Indian Congress, Indian Ambulance Corps, Burning Cauldron, Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, Hermann Kallenbach . CONTENT MILY ROY ANAND DEVELOPER SUBJECT MILY ROY ANAND COORDINATOR CIET INDU KUMAR COORDINATOR 2 Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s stay in South Africa from 1893 to 1915 was a significant chapter in the life of Gandhi. -

Way, of Spaynes Hall

SECTION XV. WAY, OF SPAYNES HALL. KATHARINECORBOULD-WARREN, of 14, Wynnstay Gardens, London, W., eldest daughter of the Rev. Wm. Corbould-Warren (see Section XIII), b. at Tacolneston 30 Jan. 1842, d. at Cranleigh, Surrey 23 Nov. 1923, bur. at Heene, Worthing. Married 3 Aug. 1864, COLONELGEORGE AUGUSTUS WAY, C.B. (1896), J.P., of Spaynes Hall, Essex, b. 6 March 1837, educ. at Eton, entered Army 18j 5, Lieut. 1858, Capt. 1867, Major 187j, Lieut. Col. 1881, served in the Punjab Frontier Force, Commandant 7th D.C.O. Rajputs, served in the Mashud Waziri exped. 1860 (medal and clasp) and Akha exped. 1883-4 (mentioned in despatches), d. 19 Oct. 1899, bur. at Heene, Worthing ; will pr. 23 Jan. 1900 ; son of the Rev. Charles John Way, M.A. Trin. Coll. Camb., of Spaynes Hall, Essex, Rector of Boreham and Chaplain to the Duke of Atholl. They had issue :- I. GEORGEJOHN WAY, of Stegi, Swaziland, South Africa, b. at Nagode, Peshawur, India 7 Aug. 1865 ; educ. at Felstead. Unmarried. 2. LEWISNORMAN WAY of Spilfeathers, Ingatestone, Essex, b. at Jubbulpore, India 23 April 1867 ; educ. at Sherborne ; d. at Spilfeathers 24 Dec. 1928 ; will proved in London 3 April 1929 Married in London 7 Jan. I 895, UNAMARGARET, b. at Mingbool, Victoria, Australia, served in V.A.D. during the Great War from 1914 to 1918, dau. of Malcolm MACKINNON, Esq., of Broadford, Isle of Skye, and Mingbool, Australia (by his wife Mary Margaret, dau. of Edward MacCallum, Esq., of Ardro, Argyllshire), and granddau. of Charles Mackinnon, Esq., of Broadford, by his wife Una, dau. -

Legacies of the Anglo-Hashemite Relationship in Jordan

Legacies of the Anglo-Hashemite Relationship in Jordan: How this symbiotic alliance established the legitimacy and political longevity of the regime in the process of state-formation, 1914-1946 An Honors Thesis for the Department of Middle Eastern Studies Julie Murray Tufts University, 2018 Acknowledgements The writing of this thesis was not a unilateral effort, and I would be remiss not to acknowledge those who have helped me along the way. First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Thomas Abowd, for his encouragement of my academic curiosity this past year, and for all his help in first, making this project a reality, and second, shaping it into (what I hope is) a coherent and meaningful project. His class provided me with a new lens through which to examine political history, and gave me with the impetus to start this paper. I must also acknowledge the role my abroad experience played in shaping this thesis. It was a research project conducted with CET that sparked my interest in political stability in Jordan, so thank you to Ines and Dr. Saif, and of course, my classmates, Lensa, Matthew, and Jackie, for first empowering me to explore this topic. I would also like to thank my parents and my brother, Jonathan, for their continuous support. I feel so lucky to have such a caring family that has given me the opportunity to pursue my passions. Finally, a shout-out to the gals that have been my emotional bedrock and inspiration through this process: Annie, Maya, Miranda, Rachel – I love y’all; thanks for listening to me rant about this all year. -

The Anglo-Boer War: an Indian Perspective

Kunapipi Volume 21 Issue 3 Article 6 1999 The Anglo-Boer War: An Indian Perspective Judith M. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Judith M., The Anglo-Boer War: An Indian Perspective, Kunapipi, 21(3), 1999. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol21/iss3/6 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Anglo-Boer War: An Indian Perspective Abstract The Anglo-Boer War is conventionally seen as part of the history of southern Africa or of British imperialism. This essay offers an Indian perspective on the conflict, in particular as it was experienced and seen through the eyes of a young Indian lawyer. M.K. Gandhi, later renowned as a religious visionary, social critic, advocate of non-violence, and a powerful opponent of British imperialism in India, in the early months of the confltct organized and helped to lead an Indian ambulance corps in the service of the government. This was one of his earliest interventions in imperial politics, for which he was honoured with an imperial medal. Such an apparently surprising episode merits attention - for it sheds light on the position of Indians in southern Africa as well as on the development of Gandhi's own thinking on a number of critical issues. This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol21/iss3/6 24 Judith M. -

Guide to the MS-236: Bernard Peace WWI Photograph Album

________________________________________________________________________ Guide to the MS-236: Bernard Peace WWI Photograph Album Kelly Murphy ‘21, Ester Kenyon Fortenbaugh ’46 Intern February 2019 MS – 236: Bernard Peace WWI Photograph Album 1 box, .175 cubic feet Inclusive Dates: 1917-1919 Processed by: Kelly Murphy, Ester Kenyon Fortenbaugh ’46 Intern (February 2019) Provenance This photo album was purchased from Between the Covers in 2016. Biographical Note Bernard Peace was born in 1884 and lived in Lockwood, a suburb of Huddersfield, England when he enlisted in the British Army. In September 1916, Private Peace completed basic training and was placed in the Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment, which mainly saw action on the Western Front. In February 1917 he was transferred to the Territorial Forces and stationed in Baghdad after its capture in March 1917. Between his arrival and his transfer home in April 1919 he stayed in Baghdad and traveled to other areas of Iraq and India when permitted. After arriving in Great Britain in November, he was transferred to the Class Z Reserve in Huddersfield.1 Although not much is known about the rest of his life, it can be presumed he left the army after the Class Z Reserve was disbanded. Historical Note The Middle Eastern theater of World War I was mainly fought between Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire. Since the Ottoman Empire was considered the weakest of the Central Powers, the British and French believed that they would be the easiest to defeat, and launched a failed naval attack on Gallipoli in 1914. They then decided on a land campaign led by the British and their colonial troops from India. -

© 2017 Irina Spector-Marks

© 2017 Irina Spector-Marks CIRCUITS OF IMPERIAL CITIZENSHIP: INDIAN PRINT CULTURE AND THE POLITICS OF RACE, 1890-1914 BY IRINA SPECTOR-MARKS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Antoinette Burton, Chair Associate Professor Teresa Barnes Associate Professor James Brennan Professor Isabel Hofmeyr, University of Witswatersand Associate Professor Dana Rabin Abstract At the turn of the twentieth century, Indian immigrants throughout the British empire faced a rise in discriminatory legislation. They responded by asserting that as imperial citizens, Indians should be treated equally with white British subjects. Although imperial citizenship had no fixed legal meaning, Indian activists invoked imperial citizenship as a legal status and as an identity that carried racial and civilizational overtones. Through a close reading of iterations of imperial citizenship across a wide range of print culture sources, I show how imperial citizenship, although ostensibly race-blind, was an implicitly racialized discourse. Based on research from archives in Ottawa, Vancouver, Durban, Pietermaritzburg, Pretoria, and London, I map how the discourse of imperial citizenship circulated across the empire in a transnational print sphere of periodicals, pamphlets, and petitions. By focusing on the work of activists in Canada and South Africa, I explore the ways in which local political and racial contexts precluded the potential for material forms of transnational collaboration. My dissertation nuances the “transnational turn” in the humanities by emphasizing the role of local factors in shaping larger global politics.