The New Yorker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lightning Bolt: Ecologia De Imagens, Ruídos E Sonoridades Extremas1

Lightning Bolt: ecologia de imagens, ruídos e sonoridades extremas1 FABRÍCIO LOPES DA SILVEIRA Resumo O artigo se detém, exclusivamente, no vídeo “Dracula Mountain”, para a música homônima do duo de noise-rock norte-americano Lightning Bolt. A intenção, de fato, é bastante restrita: trata-se de descrevê-lo e problematizá-lo, pensando-o em contraponto à sonoridade e à performance musical da banda. Ao final, sustenta-se que o vídeo é sintoma e fruto de uma ecologia midiática muito particular e contemporânea, na qual produtos e gêneros (musicais e audiovisuais), bem como Palavras-chave: hábitos de consumo (musicais e audiovisuais), são refeitos e Noise-rock, audiovisual, (re)potencializados, às vezes invertidos. ecologia da mídia VISUALIDADES, Goiânia v.9 n.2 p. 157-175, jul-dez 2011 157 Lightning Bolt: an ecology of imagens, noises and extremes sounds FABRÍCIO LOPES DA SILVEIRA Abstract The article is focused exclusively on the music video “Dracula Mountain”, by north American noise-rock band Lightning Bolt. The aim is, in fact, sufficiently restricted: to describe the video and call it in question, considering it as a counterpoint to the band sonority and musical performance. At the end, we state that the video is both a symptom and a product of a very particular and contemporary media ecology, in which musical and audiovisual products and Keywords: genres, as well as musical and audiovisual consumption Noise-rock, audiovisual, media ecology habits are rebuilt and (re)potentialized, sometimes inverted. 158 VISUALIDADES, Goiânia v.9 n.2 p. 157-175, jul-dez 2011 VISUALIDADES, Goiânia v.9 n.2 p. -

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

The New Yorker

Kindle Edition, 2015 © The New Yorker COMMENT SEARCH AND RESCUE BY PHILIP GOUREVITCH On the evening of May 22, 1988, a hundred and ten Vietnamese men, women, and children huddled aboard a leaky forty-five-foot junk bound for Malaysia. For the price of an ounce of gold each—the traffickers’ fee for orchestrating the escape—they became boat people, joining the million or so others who had taken their chances on the South China Sea to flee Vietnam after the Communist takeover. No one knows how many of them died, but estimates rose as high as one in three. The group on the junk were told that their voyage would take four or five days, but on the third day the engine quit working. For the next two weeks, they drifted, while dozens of ships passed them by. They ran out of food and potable water, and some of them died. Then an American warship appeared, the U.S.S. Dubuque, under the command of Captain Alexander Balian, who stopped to inspect the boat and to give its occupants tinned meat, water, and a map. The rations didn’t last long. The nearest land was the Philippines, more than two hundred miles away, and it took eighteen days to get there. By then, only fifty-two of the boat people were left alive to tell how they had made it—by eating their dead shipmates. It was an extraordinary story, and it had an extraordinary consequence: Captain Balian, a much decorated Vietnam War veteran, was relieved of his command and court- martialled, for failing to offer adequate assistance to the passengers. -

With LOWELL's Real Cre a 'Blueberrybb Naatural And•N T Flavored ISSUES I I I I , I I · , I I· W*E N Ee*

I I with LOWELL'S real cre a 'BlueberryBB NaAtural and•n t Flavored ISSUES I I I I , I I · , I I· _ W*e n ee* By Norman Solomon * This daily satellite-TV feed has a captive audi- * While they're about 25 percent of the U.S. pop- To celebrate the arrival of summer, here's an all- ence of more than 8 million kids in classrooms. ulation, a 1997 survey by the American Society of new episode of "Media Jeopardy!" While it's touted as "a tool to educate and engage Newspaper Editors found that they comprise You probably remember the rules: First, listen young adults in world happenings," the broad- only 11.35 percent of the journalists in the news- carefully to the answer. Then, try to come up with cast service sells commercials that go for nearly rooms of this country's daily papers. the correct question. $200,000 per half-minute -- pitched to advertisers What are racial minorities? as a way of gaining access to "the hardest to reach The first category is "Broadcast News." teen viewers." We're moving into Media Double Jeopardy with What is Channel One? our next category, "Fear and Favor." * On ABC, CBS and NBC, the amount of TV net- work time devoted to this coverage has fallen to * During the 1995-96 election cycle, these corpo- * While this California newspaper was co-spon- half of what it was during the late 1980s. rate parents of major networks gave a total of $3.2 soring a local amateur sporting event with Nike What is internationalnews? million in "soft money" to the national last spring, top editors at the paper killed a staff Democratic and Republican parties. -

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

Brian Gibson (Musician)

Brian Gibson (musician) Brian Gibson (born July 25, 1975) is a musician and artist based out of Providence, Rhode Island. Gibson is best known as the bassist for the band Lightning Bolt. Sound[edit]. Brian Gibson is particularly known for his unique and complex set-up, tuning, and use of his bass guitar. The majority of Gibson's playing draws on fairly simple loops and major/minor chord structures, yet also employs more advanced guitar techniques, such as tapping. Gibson uses a high amount of distortion, feedback and effects. Brian Gibson (born July 25, 1975) is a musician and artist based out of Providence, Rhode Island. Gibson is best known as the bassist for the band Lightning Bolt. In the summer of 2015 he co-founded the game development company Drool. At Drool, he created the art and music for the video game Thumper and co-designed the game alongside Marc Flury. Thumper was released with critical acclaim in October 2016. Bryan Gibson grew up playing baseball, riding BMX bikes, and exploring the woods of the quaint town of Orangeburg, SC. It wasnâ™t until fourteen years after his birth on New Yearâ™s Eve that he picked up a guitar and tried his hand at a set of strings. That was also the year his grandmother Gibson passed awayâ”the first major death in his life. âœUp until that time, I hadnâ™t really been exposed to mortality,â says Bryan. âœI was nowhere near being able to grasp the idea that this all wasnâ™t forever. Brian Gibson is a musician and artist based out of Providence, Rhode Island. -

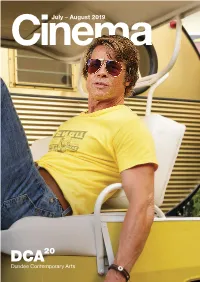

Cinema, on the Big Screen, with an Audience, Midsommar 6 Something That We Know Quentin Feels As Once Upon a Time In

CinJuly – Ae ugust 2019ma One of the most anticipated films of the summer, Contents Quentin Tarantino’s latest offering is a perfect New Films summer movie. Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood Blinded by the Light 9 o is full of energy, laughs, buddies and baddies, and The Chambermaid 8 the kind of bravado filmmaking we’ve come to love l The Dead Don’t Die 7 from this director. It is also, without a shadow of Ironstar: Summer Shorts 28 l a doubt, the kind of film that begs to be seen in The Lion King 27 a cinema, on the big screen, with an audience, Midsommar 6 something that we know Quentin feels as Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood 10 e passionately about as we do. It is a real thrill to Pain and Glory 11 be able to say Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood Photograph 8 will be shown at DCA exclusively on 35mm. We Robert the Bruce 5 can’t wait to fire up our Centurys, hear the whirr h Spider-Man: Far From Home 4 of the projectors in the booth and experience the Tell It To The Bees 7 magic of celluloid again. If you’ve never seen a film The Cure – Anniversary 13 on film, now is your chance! 197 8–2018 Live in Hyde Park Vita & Virginia 4 Another master of cinema, Pedro Almodóvar, also Documentary returns to our screens with an introspective, tender Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love 13 look at the life of an artist facing up to his regrets Of Fish and Foe 12 and the past loves who shaped him. -

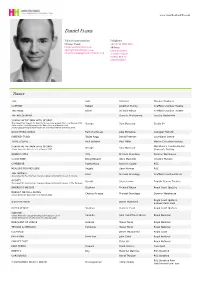

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform MIPTV 2012 tm MIPTV POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OFFILMGUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSC onnect to Seller - Buy Product MIPTVDaily Editions April 1-4, 2012 - Unabridged MIPTV Product Guide + Stills Cher Ami - Magus Entertainment - Booth 12.32 POD 32 (Mountain Road) STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE MIPTV PRODUCT GUIDE 2012 Mountain, Nature, Extreme, Geography, 10 FRANCS Water, Surprising 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, Delivery Status: Screening France 75019 France, Tel: Year of Production: 2011 Country of +33.1.487.44.377. Fax: +33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Slovakia http://www.10francs.f - email: Only the best of the best are able to abseil [email protected] into depths The Iron Hole, but even that Distributor doesn't guarantee that they will ever man- At MIPTV: Yohann Cornu (Sales age to get back.That's up to nature to Executive), Christelle Quillévéré (Sales) decide. Office: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + GOOD MORNING LENIN ! 33.6.628.04.377. Fax: + 33.1.487.48.265 Documentary (50') BEING KOSHER Language: English, Polish Documentary (52' & 92') Director: Konrad Szolajski Language: German, English Producer: ZK Studio Ltd Director: Ruth Olsman Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, Producer: Indi Film Gmbh Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Key Cast: Surprising, Judaism, Religion, Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Tradition, Culture, Daily life, Education, Delivery Status: Screening Ethnology, Humour, Interviews Year of Production: 2010 Country of Delivery Status: Screening Origin: Poland Year of Production: 2010 Country of Western foreigners come to Poland to expe- Origin: Germany rience life under communism enacted by A tragicomic exploration of Jewish purity former steel mill workers who, in this way, laws ! From kosher food to ritual hygiene, escaped unemployment. -

Un Puñado De Tesoros Que Me Han Alegrado El Año (2017)

UN PUÑADO DE TESOROS QUE ME HAN ALEGRADO EL AÑO (2017): [Instrucciones de uso: 1) Se trata de listas totalmente subjetivas, ordenadas de más a menos según el nivel de impacto que me ha provocado cada referència. 2) Desgloso la lista de discos de 2017 en elepés, canciones y versiones para intentar hacerla menos larga, pero obviamente los títulos de la segunda y tercera lista podrían estar en la primera (especialmente los de las primeras posiciones) y viceversa. Ídem con la lista de conciertos. 3) Todas las obras de estas listas me parecen absolutamente recomendables, aunque no sean necesariamente las mejores de sus autores, sino simplemente los que me han acompañado durante los últimos doce meses. 4) Espero que disfrutéis descubriendo o redescubriendo unas cuantas joyas.] JC Badlands aka Arnold Layne ( @EbonyWhite) 50 excitantes discos publicados en 2017: THE MAGNETIC FIELDS: 50 Song Memoir PETER PERRETT: How The West Was Won LCD SOUNDSYSTEM: American Dream BASH & POP: Anything Could Happen ZEBRA HUNT: In Phrases THE NEW YEAR: Snow WADADA LEO SMITH: Najwa KENDRICK LAMAR: DAMN. HURRAY FOR THE RIFF RAFF: The Navigator KARL BLAU: Out Her Space ALDOUS HARDING: Party RICHARD DAWSON: Peasant SLEAFORD MODS: English Tapas ROBYN HITCHCOCK: Robyn Hitchcock LITTLE BARRIE: Death Express THURSTON MOORE: Rock'n'Roll Consciousness LEE RANALDO: Electric Trim THE DREAM SYNDICATE: How Did I Find Myself Here? MATTHEW SWEET: Tomorrow Forever MARK EITZEL: Hey, Mr. Ferryman LAURA MARLING: Semper Femina PAUL KELLY: Life Is Fine RAY DAVIES: Americana LINDA PERHACS: I'm A Harmony VALPARAISO: Broken Homeland KEVIN MORBY: City Music CHUCK PROPHET: Bobby Fuller Died for Your Sins THE SADIES: Northern Passages KELLEY STOLTZ: Que Aura THE AFGHAN WHIGS: In Spades ENDLESS BOOGIE: Vibe Killer MAVIS STAPLES: If All I Was Was Black TY SEGALL: Ty Segall JESU / SUN KIL MOON: 30 Seconds To The Decline Of Planet Earth HALF JAPANESE: Hear The Lions Roar THE MOUNTAIN GOATS: Goths MARK MULCAHY: The Possum In The Driveway IMELDA MAY: Life. -

10700990.Pdf

The Dolby era: Sound in Hollywood cinema 1970-1995. SERGI, Gianluca. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20344/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20344/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Sheffield Hallam University jj Learning and IT Services j O U x r- U u II I Adsetts Centre City Campus j Sheffield Hallam 1 Sheffield si-iwe Author: ‘3£fsC j> / j Title: ^ D o ltiu £ r a ' o UJTvd 4 c\ ^ £5ori CuCN^YTNCa IQ IO - Degree: p p / D - Year: Q^OO2- Copyright Declaration I recognise that the copyright in this thesis belongs to the author. I undertake not to publish either the whole or any part of it, or make a copy of the whole or any substantial part of it, without the consent of the author. I also undertake not to quote or make use of any information from this thesis without making acknowledgement to the author. Readers consulting this thesis are required to sign their name below to show they recognise the copyright declaration. They are also required to give their permanent address and date. -

Nero Magazine

2 / QUI GIACE L’HARD ROCK 4 / BRENT GREEN 8 / EARTH 10 / POLAROID 12 / SILENCE IS SEXY 16 / TO BE CONTINUED... 19 / RIMEDIARE LA REALTA NER O 21 / GARDAR EIDE EINARSSON 26 / SPLITTING 29 / FIGLI DI NUGGETS Neromagazine.it 30 / ALICE IN SYNCHRONICITY 32 / JAPAN DIGITAL MUTATION GIRLS: SAWAKO 34 / WHITE E PORK 36 / RECENSIONI 44 / NERO INDEX 45 / NERO TAPES BIMESTRALE A DISTRIBUZIONE GRATUITA NUMERO 7 DICEMBRE / GENNAIO 2006 Direttore Responsabile: Giuseppe Mohrhoff Direzione Editoriale: Francesco de Figueiredo ([email protected]) Luca Lo Pinto ([email protected]) Valerio Mannucci ([email protected]) Lorenzo Micheli Gigotti ([email protected]) Staff di Redazione: Emiliano Barbieri, Rudi Borsella, Marco Cirese, Ilaria Gianni, Andrea Proia, Francesco Tatò, Francesco Ventrella Collaboratori: Gianni Avella, Marco Costa, Silvia Chiodi, France- sco Farabegoli, Roberta Ferlicca, Francesca Izzi, Alberto Lo Pinto, Federico Narracci,Anna Passarini, Silvia Pirolli, Leandro Pisano, Marta Pozzoli, Francesco M. Russo,Giordano Simoncini, Davide Talia Grafica: Daniele De Santis ([email protected] Industrie Grafiche di Roma) Responsabile Illustrazioni: Carola Bonfili (carolabonfi[email protected]) Invio Materiale: Via degli Scialoja,18 - 00196 ROMA Pubblicità: [email protected] Lorenzo Micheli Gigotti 3391453359 Distribuzione: [email protected] Editore: Produzioni NERO soc. coop. a r.l. Iscrizione Albo Cooperative n° A116843 NERO Largo Brindisi, 5 - 00182 ROMA Tel. / Fax 06 97271252 [email protected] Registrazione al Tribunale di Roma n. 102/04 del 15 marzo 2004 Stampa: OK PRINT via Calamatta 16, ROMA Distribuzione a Milano a cura di Promos Comunicazione www.promoscomunicazione.it copertina di Nicola Pecoraro www.hopaura.org – [email protected] sommario di Carola Bomfili NERO A CASA.