Teaching Hard History: a Framework for Teaching American Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoirs of Boston King

Module 03: A Revolution for Whom? Evidence 2: Memoirs of Boston King Introduction Even without proclamations from royal officials, slaves throughout the American colonies left their masters and went in search of the British army. Boston King, a young South Carolina slave, was one of the thousands of African Americans who joined the British between 1775 and 1781. Boston King was also one of several thousand former slaves who, in remaining with the British when the Revolution ended, left the only homes they had ever known but gained their freedom. Questions to Consider • Why did Boston King run away? • What role or roles did King serve with the British? • What do King's language and actions suggest about his feelings for the British? • What did the American Revolution do for Boston King? Document I was born in the Province of South Carolina, 28 miles from Charles Town. My father was stolen away from Africa when he was young. I have reason to believe that he lived in the fear and love of God. He was beloved by this master, and had the charge of the Plantation as a driver for many years. In his old age he was employed as a mill-cutter. My mother was employed chiefly in attending upon those that were sick, having some knowledge of the virtue of herbs, which she learned from the Indians. She likewise had the care of making the people's clothes, and on these accounts was indulged with many privileges which the rest of the slaves were not When I was six years old I waited in the house upon my master. -

Puritan Pedagogy in Uncle Tom's Cabin

Molly Dying Instruction: Puritan Pedagogy in Farrell Uncle Tom’s Cabin To day I have taken my pen from the last chapter of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” . It has been the most cheering thing about the whole endeavor to me, that men like you, would feel it. —Letter from Harriet Beecher Stowe to Horace Mann, 2 March 1852 n 1847, three years before Harriet Beecher Stowe I began Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Horace Mann and his wife Mary offered Miss Chloe Lee, a young black student who had been admitted to the Normal School in West Newton, the spare room in their Massachusetts home.1 Mann had recently been corresponding with Stowe’s sister Catherine Beecher about their shared goals for instituting a new kind of edu- cation that would focus more on morals than on classical knowledge and would target the entire society. Beecher enthusiastically asserted that with this inclusive approach, she had “no hesitation in saying, I do not believe that one, no, not a single one, would fail of proving a respectable and prosperous member of society.”2 There were no limits to who could be incorporated into their educational vision—a mission that would encompass even black students like Lee. Arising from the evangelical tradition of religious teaching, these educators wanted to change the goal of the school from the preparation of leaders to the cultivation of citizens. This work of acculturation—making pedagogy both intimate and all-encompassing—required educators to replace the role of parents and turn the school into a multiracial family. Stowe and her friends accordingly had to imagine Christian instruction and cross-racial connection as intimately intertwined. -

Sample Slavery and Human Trafficking Statement

KASAI UK LTD Gender Pay Report At Kasai we are committed to treating our people equally and ensuring that everyone – no matter what their background, race, ethnicity or gender – has an opportunity to develop. We are confident that our gender pay gap is not caused by men and woman being paid differently to do the same job but is driven instead by the structure of our workforce which is heavily male dominated. As of the snapshot date the table below shows our overall mean and median gender pay gap and bonus pay based on hourly rates of pay. Difference between men and woman Mean (Average) Median (Mid-Range) Hourly Pay Gap 18.1% 20.9% Bonus Pay Gap 0% 0% Quartiles We have divided our population into four equal – sized pay quartiles. The graphs below show the percentage of males and females in each of these quartiles Upper Quartiles 94% males 6% females -5.70% Upper middle quartiles 93% male 7% females -1.30% Lower middle quartiles 87% male 13% females 2.39% Lower Quartiles 76% male 24% females 3.73% Analysis shows that any pay gap does not arise from male and females doing the same job / or same level and being paid differently. Females and males performing the same role and position, have the same responsibility and parity within salary. What is next? We are confident that our male and female employees are paid equally for doing equivalent jobs across our business. We will continue to monitor gender pay throughout the year. Flexible working and supporting females through maternity is a key enabler in retaining and developing female’s talent in the future business. -

A Framework for Teaching American Slavery

K–5 FRAMEWORK TEACHING HARD HISTORY A FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHING AMERICAN SLAVERY ABOUT THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER The Southern Poverty Law Center, based in Montgomery, Alabama, is a nonpar- tisan 501(c)(3) civil rights organization founded in 1971 and dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry, and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of society. ABOUT TEACHING TOLERANCE A project of the Southern Poverty Law Center founded in 1991, Teaching Tolerance is dedicated to helping teachers and schools prepare children and youth to be active participants in a diverse democracy. The program publishes Teaching Tolerance magazine three times a year and provides free educational materials, lessons and tools for educators commit- ted to implementing anti-bias practices in their classrooms and schools. To see all of the resources available from Teaching Tolerance, visit tolerance.org. © 2019 SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER Teaching Hard History A K–5 FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHING AMERICAN SLAVERY 2 TEACHING TOLERANCE // TEACHING HARD HISTORY // A FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHING AMERICAN SLAVERY CONTENTS Introduction 4 About the Teaching Hard History Elementary Framework 6 Grades K-2 10 Grades 3-5 18 Acknowledgments 28 Introduction Teaching about slavery is hard. It’s especially hard in elementary school classrooms, where talking about the worst parts of our history seems at odds with the need to motivate young learners and nurture their self-confidence. Teaching about slavery, especially to children, challenges educators. Those we’ve spoken with—especially white teachers—shrink from telling about oppression, emphasizing tales of escape and resistance instead. They worry about making black students feel ashamed, Latinx and Asian students feel excluded and white students feel guilty. -

Religion of the South” and Slavery Selections from 19Th-Century Slave Narratives

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 ON THE “RELIGION OF THE SOUTH” AND SLAVERY SELECTIONS FROM 19TH-CENTURY SLAVE NARRATIVES * In several hundred narratives, many published by abolitionist societies in the U.S. and England, formerly enslaved African Americans related their personal experiences of enslavement, escape, and freedom in the North. In straight talk they condemned the “peculiar institution” ⎯ its dominance in a nation that professed liberty and its unyielding defense by slaveholders who professed Christianity. “There is a great difference between Christianity and religion at the south,” writes Harriet Jacobs; Frederick Douglass calls it the “the widest, possible difference ⎯ so wide, that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked.”1 Presented here are four nineteenth-century African American perspectives on the “religion of the south.” Frederick Douglass “the religion of the south . is a mere covering for the most horrid crimes” I assert most unhesitatingly that the religion of the south ⎯ as I have observed it and proved it ⎯ is a mere covering for the most horrid crimes, the justifier of the most appalling barbarity, a sanctifier of the most hateful frauds, and a secure shelter under which the darkest, foulest, grossest, and most infernal abominations fester and flourish. Were I again to be reduced to the condition of a slave, next to that calamity, I should regard the fact of being the slave of a religious slaveholder the greatest that could befall me. For of all slaveholders with whom I have ever met, religious slaveholders are the worst. -

Omar Ibn Said a Spoleto Festival USA Workbook Artwork by Jonathan Green This Workbook Is Dedicated to Omar Ibn Said

Omar Ibn Said A Spoleto Festival USA Workbook Artwork by Jonathan Green This workbook is dedicated to Omar Ibn Said. About the Artist Jonathan Green is an African American visual artist who grew up in the Gullah Geechee community in Gardens Corner near Beaufort, South Carolina. Jonathan’s paintings reveal the richness of African American culture in the South Carolina countryside and tell the story of how Africans like Omar Ibn Said, managed to maintain their heritage despite their enslavement in the United States. About Omar Ibn Said This workbook is about Omar Ibn Said, a man of great resilience and perseverance. Born around 1770 in Futa Toro, a rich land in West Africa that is now in the country of Senegal on the border of Mauritania, Omar was a Muslim scholar who studied the religion of Islam, among other subjects, for more than 25 years. When Omar was 37, he was captured, enslaved, and transported to Charleston, where he was sold at auction. He remained enslaved until he died in 1863. In 1831, Omar wrote his autobiography in Arabic. It is considered the only autobiography written by an enslaved person—while still enslaved—in the United States. Omar’s writing contains much about Islam, his religion while he lived in Futa Toro. In fact, many Africans who were enslaved in the United States were Muslim. In his autobiography, Omar makes the point that Christians enslaved and sold him. He also writes of how his owner, Jim Owen, taught him about Jesus. Today, Omar’s autobiography is housed in the Library of Congress. -

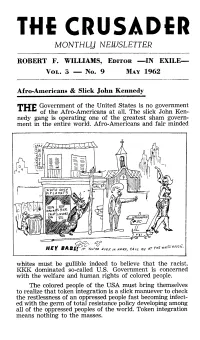

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

The End of Uncle Tom

1 THE END OF UNCLE TOM A woman, her body ripped vertically in half, introduces The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven from 1995 (figs.3 and 4), while a visual narra- tive with both life and death at stake undulates beyond the accusatory gesture of her pointed finger. An adult man raises his hands to the sky, begging for deliverance, and delivers a baby. A second man, obese and legless, stabs one child with his sword while joined at the pelvis with another. A trio of children play a dangerous game that involves a hatchet, a chopping block, a sharp stick, and a bucket. One child has left the group and is making her way, with rhythmic defecation, toward three adult women who are naked to the waist and nursing each other. A baby girl falls from the lap of one woman while reaching for her breast. With its references to scatology, infanticide, sodomy, pedophilia, and child neglect, this tableau is a troubling tribute to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin—the sentimental, antislavery novel written in 1852. It is clearly not a straightfor- ward illustration, yet the title and explicit references to racialized and sexualized violence on an antebellum plantation leave little doubt that there is a significant relationship between the two works. Cut from black paper and adhered to white gallery walls, this scene is composed of figures set within a landscape and depicted in silhouette. The medium is particularly apt for this work, and for Walker’s project more broadly, for a number of reasons. -

Hair: the Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960S’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Winchester Research Repository University of Winchester ‘Hair: The Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960s’ Sarah Elisabeth Browne ORCID: 0000-0003-2002-9794 Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester MPhil/PhD THESES OPEN ACCESS / EMBARGO AGREEMENT FORM This Agreement should be completed, signed and bound with the hard copy of the thesis and also included in the e-copy. (see Thesis Presentation Guidelines for details). Access Permissions and Transfer of Non-Exclusive Rights By giving permission you understand that your thesis will be accessible to a wide variety of people and institutions – including automated agents – via the World Wide Web and that an electronic copy of your thesis may also be included in the British Library Electronic Theses On-line System (EThOS). Once the Work is deposited, a citation to the Work will always remain visible. Removal of the Work can be made after discussion with the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, who shall make best efforts to ensure removal of the Work from any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement. Agreement: I understand that the thesis listed on this form will be deposited in the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, and by giving permission to the University of Winchester to make my thesis publically available I agree that the: • University of Winchester’s Research Repository administrators or any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement to do so may, without changing content, translate the Work to any medium or format for the purpose of future preservation and accessibility. -

Texts Checklist, the Making of African American Identity

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 A collection of primary resources—historical documents, literary texts, and works of art—thematically organized with notes and discussion questions I. FREEDOM pages ____ 1 Senegal & Guinea 12 –Narrative of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (Job ben Solomon) of Bondu, 1734, excerpts –Narrative of Abdul Rahman Ibrahima (“the Prince”), of Futa Jalon, 1828 ____ 2 Mali 4 –Narrative of Boyrereau Brinch (Jeffrey Brace) of Bow-woo, Niger River valley, 1810, excerpts ____ 3 Ghana 6 –Narrative of Broteer Furro (Venture Smith) of Dukandarra, 1798, excerpts ____ 4 Benin 11 –Narrative of Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua of Zoogoo, 1854, excerpts ____ 5 Nigeria 18 –Narrative of Olaudah Equiano of Essaka, Eboe, 1789, excerpts –Travel narrative of Robert Campbell to his “motherland,” 1859-1860, excerpts ____ 6 Capture 13 –Capture in west Africa: selections from the 18th-20th-century narratives of former slaves –Slave mutinies, early 1700s, account by slaveship captain William Snelgrave FREEDOM: Total Pages 64 II. ENSLAVEMENT pages ____ 1 An Enslaved Person’s Life 36 –Photographs of enslaved African Americans, 1847-1863 –Jacob Stroyer, narrative, 1885, excerpts –Narratives (WPA) of Jenny Proctor, W. L. Bost, and Mary Reynolds, 1936-1938 ____ 2 Sale 15 –New Orleans slave market, description in Solomon Northup narrative, 1853 –Slave auctions, descriptions in 19th-century narratives of former slaves, 1840s –On being sold: selections from the 20th-century WPA narratives of former slaves, 1936-1938 ____ 3 Plantation 29 –Green Hill plantation, Virginia: photographs, 1960s –McGee plantation, Mississippi: description, ca. 1844, in narrative of Louis Hughes, 1897 –Williams plantation, Louisiana: description, ca. -

Image Credits, the Making of African

THE MAKING OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY: VOL. I, 1500-1865 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 IMAGE CREDITS Items listed in chronological order within each repository. ALABAMA DEPT. of ARCHIVES AND HISTORY. Montgomery, Alabama. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Physical and Political Map of the Southern Division of the United States, map, Boston: William C. Woodbridge, 1843; adapted to Woodbridges Geography, 1845; map database B-315, filename: se1845q.sid. Digital image courtesy of Alabama Maps, University of Alabama. ALLPORT LIBRARY AND MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS. State Library of Tasmania. Hobart, Tasmania (Australia). WEBSITE Reproduced by permission of the Tasmanian Archive & Heritage Office. —Mary Morton Allport, Comet of March 1843, Seen from Aldridge Lodge, V. D. Land [Tasmania], lithograph, ca. 1843. AUTAS001136168184. AMERICAN TEXTILE HISTORY MUSEUM. Lowell, Massachusetts. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Wooden snap reel, 19th-century, unknown maker, color photograph. 1970.14.6. ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. WEBSITE In the public domain; reproduced courtesy of Archives of Ontario. —Letter from S. Wickham in Oswego, NY, to D. B. Stevenson in Canada, 12 October 1850. —Park House, Colchester, South, Ontario, Canada, refuge for fugitive slaves, photograph ca. 1950. Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F2076-16-6. —Voice of the Fugitive, front page image, masthead, 12 March 1854. F 2076-16-935. —Unidentified black family, tintype, n.d., possibly 1850s; Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F 2076-16-4-8. ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY. Wilmore, Kentucky. Permission requests submitted. –“Slaves being sold at public auction,” illustration in Thomas Lewis Johnson, Twenty-Eight Years a Slave, or The Story of My Life in Three Continents, 1909, p. -

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave How to analyze slave narratives. Who Was Solomon Northup? 1808: Born in Minerva, NewYork Son of former slave, Mintus Northup; Northup's mother is unknown. 1829: Married Anne Hampton, a free black woman. They had three children. Solomon was a farmer, a rafter on the Lake Champlain Canal, and a popular local fiddler. What Happened to Solomon Northup? Met two circus performers who said they needed a fiddler for engagements inWashington, D.C. Traveled south with the two men. Didn't tell his wife where he was going (she was out of town); he expected to be back by the time his family returned. Poisoned by the two men during an evening of social drinking inWashington, D.C. Became ill; he was taken to his room where the two men robbed him and took his free papers; he vaguely remembered the transfer from the hotel but passed out. What Happened…? • Awoke in chains in a "slave pen" in Washington, D.C., owned by infamous slave dealer, James Birch. (Note: A slave pen were where (Note:a slave pen was where slaves were warehoused before being transported to market) • Transported by sea with other slaves to the New Orleans slave market. • Sold first toWilliam Prince Ford, a cotton plantation owner. • Ford treated Northup with respect due to Northup's many skills, business acumen and initiative. • After six months Ford, needing money, sold Northup to Edwin Epps. Life on the Plantation Edwin Epps was Northup’s master for eight of his 12 years a slave.