This May Be the Author's Version of a Work That Was Submitted/Accepted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate Crossbench Background 2016

Barton Deakin Brief: Senate Crossbench 4 August 2016 The 2016 federal election resulted in a large number of Senators elected that were not members of the two major parties. Senators and Members of the House of Representatives who are not part of the Coalition Government or the Labor Opposition are referred to collectively as the Senate ‘crossbench’. This Barton Deakin Brief outlines the policy positions of the various minor parties that constitute the crossbench. Background Due to the six year terms of Senators, at a normal election (held every three years) only 38 of the Senate’s 76 seats are voted on. As the 2016 federal election was a double dissolution election, all 76 seats were contested. To pass legislation a Government needs 39 votes in the Senate. As the Coalition won just 30 seats it will have to rely on the support of minor parties and independents to pass legislation when it is opposed by Labor. Since the introduction of new voting reforms in the Senate, minor parties can no longer rely on the redistribution of above-the-line votes according to preference flows to satisfy the 14.3% quota (or, in the case of a double dissolution, 7.7%) needed to win a seat in Senate elections. The new Senate voting reforms allowed voters to control their preferences by numbering all candidates above the line, thereby reducing the effectiveness of preference deals that have previously resulted in Senators being elected with a small fraction of the primary vote. To read Barton Deakin’s Brief on the Senate Voting Reforms, click here. -

24 April 2018 Mr Grant Hehir Auditor-General Australian National

PARLIAMENT OF AUSTRALIA 24 April 2018 Mr Grant Hehir Auditor-General Australian National Audit Office 19 National Circuit Barton ACT 2600 By email: [email protected] Dear Auditor-General Allegations concerning the Murray-Darling Basin Plan We refer to the allegations raised in analysis by The Australia Institute (enclosed) and various media reports relating to the purchases of water for environmental flows in the Murray-Darling Basin. The analysis and reports allege that the Department of Agriculture and Resources, which manages the purchase of water, significantly overpaid vendors for water in the Warrego catchment, Tandou and the Condamine-Balonne Valley. If true, this would mean that the Federal Government has not achieved value-for-money for the taxpayer in executing the Murray-Darling Basin Plan. Accordingly, we ask you to investigate these allegations and any other matter you consider relevant arising out of the analysis conducted by The Australia Institute including, but not limited to, all purchases of water by the Commonwealth to ensure they have met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. Yours sincerely, Rex Patrick Stirling Griff Rebekha Sharkie MP Senator for South Australia Senator for South Australia Member for Mayo Sarah Hanson-Young The Hon. Tony Burke Cory Bernardi Senator for South Australia Member for Watson Senator for South Australia PO Box 6100, Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 That’s not how you haggle…. Commonwealth water purchasing in the Condamine Balonne The Australian Government bought 29 gigalitres of water for $80m in the Condamine-Balonne valley. The vendors originally insisted on $2,200 per megalitre. -

Pirates of the Australian Election Matthew Rimmer, Australian National University College of Law

Queensland University of Technology From the SelectedWorks of Matthew Rimmer March 26, 2013 Pirates of the Australian Election Matthew Rimmer, Australian National University College of Law Available at: https://works.bepress.com/matthew_rimmer/151/ Pirates of the Australian Election The Global Mail Dr Matthew Rimmer “Pirate parties” have proliferated across Europe and North America in the past decade, championing issues such as intellectual property (IP), freedom of speech, and the protection of privacy and anonymity. This year, the movement hit Australian shores: The Pirate Party Australia was officially registered by the Australian Electoral Commission in January 2013. (You can read its principles and platform here.) “More than ever before, there is a necessity in Australia for a party that holds empowerment, participation, free culture and openness as its central tenets”, Pirate Party founder Rodney Serkowski said in a press release announcing the group’s successful registration. Their first test will be this year’s federal election, scheduled for September 14, in which the fledgling party will contest Senate seats in New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria. There has been much political discussion as to how Pirate Party Australia will fare in September’s poll. The Swedish Piratpartiet has two members in the European Parliament. The German Pirate Party has won seats in regional and municipal elections. The Czech Pirate Party had a member elected to the national parliament. But pirate parties contesting elections in the United Kingdom and North American have failed to make an electoral impact. Will Pirate Party Australia emulate the success of its European counterparts? Or will the Pirate Party Australia struggle to gain attention and votes as a micro-party in a crowded field? They might find that the times suit them: this year’s election is shaping up as a battle royal over IP. -

KJA Action Items Template

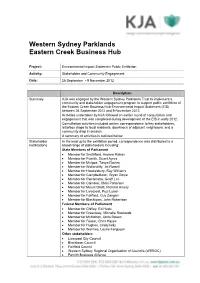

Western Sydney Parklands Eastern Creek Business Hub Project: Environmental Impact Statement Public Exhibition Activity: Stakeholder and Community Engagement Date: 26 September - 9 November 2012 Description Summary KJA was engaged by the Western Sydney Parklands Trust to implement a community and stakeholder engagement program to support public exhibition of the Eastern Creek Business Hub Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) between 26 September 2012 and 9 November 2012. Activities undertaken by KJA followed an earlier round of consultation and engagement that was completed during development of the EIS in early 2012. Consultation activities included written correspondence to key stakeholders, letterbox drops to local residents, doorknock of adjacent neighbours, and a community drop in session. A summary of activities is outlined below. Stakeholder In the lead up to the exhibition period, correspondence was distributed to a notifications broad range of stakeholders including: State Members of Parliament Member for Smithfield, Andrew Rohan Member for Penrith, Stuart Ayres Member for Mulgoa, Tanya Davies Member for Wollondilly, Jai Rowell Member for Hawkesbury, Ray Williams Member for Campbelltown, Bryan Doyle Member for Parramatta, Geoff Lee Member for Camden, Chris Patterson Member for Mount Druitt, Richard Amery Member for Liverpool, Paul Lynch Member for Fairfield, Guy Zangari Member for Blacktown, John Robertson Federal Members of Parliament Member for Chifley, Ed Husic Member for Greenway, Michelle Rowlands Member for -

Evobzq5zilluk8q2nary.Pdf

NOVEMBER 10 (GMT) – NOVEMBER 11 (AEST), 2020 YOUR DAILY TOP 12 STORIES FROM FRANK NEWS FULL STORIES START ON PAGE 3 NORTH AMERICA UK AUSTRALIA Trump blocks co-operation Optimism over vaccine rollout MP quits Labor frontbench The Trump administration threw the A coronavirus vaccine could start being Labor right faction warrior Joel Fitzgibbon presidential transition into tumult, distributed by Christmas after a jab has urged his party to make a major with President Donald Trump blocking developed by pharmaceutical giant shift on the environment and blue-collar government officials from co-operating Pfizer cleared a “significant hurdle”. voters after quitting shadow cabinet. with President-elect Joe Biden’s team Prime Minister Boris Johnson said initial Western Sydney MP Ed Husic replaced and Attorney General William Barr results suggested the vaccine was 90 per Fitzgibbon as the opposition’s resources authorizing the Justice Department to cent effective at protecting people from and agriculture spokesman after the probe unsubstantiated allegations of COVID-19 but warned these were “very, stunning resignation. Fitzgibbon has voter fraud. Some Republicans, including very early days”. been increasingly outspoken in a bruising Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, battle over energy policy with senior rallied behind Trump’s efforts to fight the figures from Labor’s left flank. election results. NORTH AMERICA UK NEW ZEALAND Election probes given OK Redundancies hit record high Napier braces for heavy rain Attorney General William Barr has More people were made redundant Flood-hit Napier residents remain on authorized federal prosecutors across between July and September than at any alert as more heavy rain is falling on the US to pursue “substantial allegations” point on record, according to new official the city, with another day of rain still to of voting irregularities, if they exist, before statistics, as the pandemic laid waste come. -

What Will a Labor Government Mean for Defence Industry in Australia?

What will a Labor Government mean for Defence Industry in Australia? Hon Greg Combet AM Opinion polls suggest a change of government in the Australian Federal election in (expected) May 2019. An incoming Labor Government led by Bill Shorten will likely feature Richard Marles as Minister for Defence and Mike Kelly as Assisting Minister for Defence Industry and Support. Jason Clare, a former Minister for Defence Matériel, would likely have influence upon the defence industry portfolio in his potential role as Minister for Trade and Investment. Under a Labor Government, it is possible Shorten would appoint a new Minister for Defence Matériel (as has been an established practice for many years) given the magnitude of expenditure and complexity of the portfolio. Shorten and Marles have been associates since university and have been closely aligned during their trade union and political careers. With extensive practical experience of the Australian industry, Shorten and Marles have a record of working constructively with business leadership. Both have a sound understanding of the role and the significance of defence industry in Australia. Marles, in particular, has a greater interest in national security and strategic issues and would likely concentrate on these in the portfolio and delegate aspects of defence industry to a ministerial colleague. Labor’s defence industry policy was reviewed and adopted during the December 2018 Party National Conference. The policy is consistent with Labor’s approach when it was last in government, reiterating support for: • an Australian defence industry that provides the Australian Defence Force with the necessary capabilities; • sovereign industrial capability where required, specifically identifying naval shipbuilding; • an export focus; • the maximisation of the participation of small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) in defence projects; and • initiatives to develop workforce skills. -

Commonwealth of Australia

Commonwealth of Australia Author Wanna, John Published 2019 Journal Title Australian Journal of Politics and History Version Accepted Manuscript (AM) DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/ajph.12576 Copyright Statement © 2019 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics, School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Journal of Politics and History, Volume 65, Issue 2, Pages 295-300, which has been published in final form at 10.1111/ajph.12576. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/388250 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Commonwealth of Australia John Wanna Turnbull’s Bizarre Departure, and a Return to Minority Government for the Morrison-led Coalition Just when political pundits thought federal parliament could not become even wackier than it had been in recent times, the inhabitants of Capital Hill continued to prove everyone wrong. Even serious journalists began referring to the national legislature metaphorically as the “monkey house” to encapsulate the farcical behaviour they were obliged to report. With Tony Abbott being pre-emptively ousted from the prime ministership by Malcolm Turnbull in 2015, Turnbull himself was, in turn, unceremoniously usurped in bizarre circumstances in August 2018, handing over the leadership to his slightly bemused Treasurer Scott Morrison. Suddenly, Australia was being branded as the notorious “coup capital of the Western democracies”, with five prime ministers in five years and only one losing the high office at a general election. -

Activities & Achievements

Activities & July-September 2016 Achievements July-September 2016 Highlights CEO: James Pearson This quarter we have sought to put into action the policies in our Top 10 in 10 election manifesto to improve Australia’s international competitiveness. To achieve results on these policies we are continuing our public advocacy while seeking to connect with key members of parliament. Minister for Small Business Michael McCormack MP, with Victorian Chamber CEO Mark Stone AM and Australian Chamber President Terry Wetherall Over the quarter Mr Pearson spoke prominently on behalf of in Melbourne. business, undertaking dozens of interviews across broadcast, print and digital media, writing several opinion pieces and maintaining a We welcomed to the team Jennifer Low (Acting Director of Work strong presence on social media. Health and Safety and Workers’ Compensation Policy), Jessica Wright (Media and Stakeholder Engagement Manager), Julie Chan As part of our parliamentary advocacy, we met with more than (Economic and Industry Senior Policy Adviser), Joe Doleschal- 15 ministers and shadow ministers, including Treasurer Scott Ridnell (National Policy Adviser), Gemma Sandlant (Employment, Morrison, Trade Minister Steve Ciobo, Shadow Finance Minister Jim Education and Training Policy Adviser), Lewis Hirst (Trade and Chalmers and Shadow Small Business Minister Katy Gallagher. We International Affairs Adviser) and Fen Cai (Finance Officer, on a also met representatives from crossbenchers in the Senate. maternity leave placement). We also farewelled several staff. In partnership with our state and territory chambers of commerce, we are hosting events to connect Small Business Minister Michael McCormack with small businesses across the country. We started with successful events in Launceston and Melbourne. -

Winning Respect@Work on Monday 9 August, the ACTU Provided a Briefing Regarding the Respect@ Work Bill

Winning Respect@Work On Monday 9 August, the ACTU provided a briefing regarding the Respect@ Work Bill. Unionists have been called to action. Background Every day unions support members who have been sexually harassed at work According to the Australian Unions survey undertaken in 2018, two in three women and one in three men have experienced sexual harassment. There is a plan to make work safer, especially for women. The landmark Australian Human Rights Commission Respect@Work report has 55 recommendations to create stronger rights to eliminate sexual harassment. The Federal Government sat on this report for over a year before it was forced to act . It now has a Bill before the Parliament, cherry-picking some recommendations but ignoring the very ones that would make the biggest contribution to ensuring women are safe at work. The Federal Government will put forward the Respect@ Work Bill to Parliament on Wednesday 11 August. Do not be misled by its title. This Bill is a watered-down version of what the AHRC report had recommended. The Bill must be amended to be fit for purpose in four key ways: 1.Amended so that the Fair Work Act prohibits sexual harassment (then it becomes a workplace right and workers’ also have easy access to justice). 2.Amended so the Sex Discrimination Act – it to have ‘positive duties’ where employers are legally obligated to prevent harassment in the workplace, not simply deal with complaints. 3.Amended so the Commissioner can intervene in systemic issues. Sex Discrimination Commissioner can currently only respond to individual complaints; we want the act amended so the Commissioner can intervene in systemic issues. -

Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45Th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief Lists

Barton Deakin Brief: Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief lists individuals and institutions on Twitter relevant to policy and political developments in the federal government domain. These institutions and individuals either break policy-political news or contribute in some form to “the conversation” at national level. Being on this list does not, of course, imply endorsement from Barton Deakin. This Brief is organised by categories that correspond generally to portfolio areas, followed by categories such as media, industry groups and political/policy commentators. This is a “living” document, and will be amended online to ensure ongoing relevance. We recognise that we will have missed relevant entities, so suggestions for inclusions are welcome, and will be assessed for suitability. How to use: If you are a Twitter user, you can either click on the link to take you to the author’s Twitter page (where you can choose to Follow), or if you would like to follow multiple people in a category you can click on the category “List”, and then click “Subscribe” to import that list as a whole. If you are not a Twitter user, you can still observe an author’s Tweets by simply clicking the link on this page. To jump a particular List, click the link in the Table of Contents. Barton Deakin Pty. Ltd. Suite 17, Level 2, 16 National Cct, Barton, ACT, 2600. T: +61 2 6108 4535 www.bartondeakin.com ACN 140 067 287. An STW Group Company. SYDNEY/MELBOURNE/CANBERRA/BRISBANE/PERTH/WELLINGTON/HOBART/DARWIN -

Federal Labor Shadow Ministry January 2021

Federal Labor Shadow Ministry January 2021 Portfolio Minister Leader of the Opposition The Hon Anthony Albanese MP Shadow Cabinet Secretary Senator Jenny McAllister Deputy Leader of the Opposition The Hon Richard Marles MP Shadow Minister for National Reconstruction, Employment, Skills and Small Business Shadow Minister for Science Shadow Minister Assisting for Small Business Matt Keogh MP Shadow Assistant Minister for Employment and Skills Senator Louise Pratt Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator the Hon Penny Wong Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Shadow Minister for International Development and the Pacific Pat Conroy MP Shadow Assistant Minister to the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator Jenny McAllister Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally Shadow Minister for Home Affairs Shadow Minister for Immigration and Citizenship Shadow Minister for Government Accountability Shadow Minister for Multicultural Affairs Andrew Giles MP Shadow Minister Assisting for Immigration and Citizenship Shadow Minister for Disaster and Emergency Management Senator Murray Watt Shadow Minister Assisting on Government Accountability Pat Conroy MP Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations The Hon Tony Burke MP Shadow Minister for the Arts Manager of Opposition Business in the House of Representatives Shadow Special Minister of State Senator the Hon Don Farrell Shadow Minister for Sport and Tourism Shadow Minister Assisting the Leader of the Opposition Shadow Treasurer Dr Jim Chalmers MP Shadow Assistant -

Australia-China Relations Summary August 2018 Edition

澳大利亚-中国关系研究院Australia-China Relations Institute 澳大利亚-中国关系研究院 August 2018 Australia-China relations summary August 2018 edition Elena Collinson The latest developments in Australia-China relations in August 2018. Ministerial engagement Then-Foreign Minister Julie Bishop met with PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi on August 4 on the sidelines of the East Asia Summit Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Singapore. Following the meeting, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) released a statement which pointedly opened with the line that the Chinese Foreign Minister had ‘met at request’ with the Australian Foreign Minister. An MFA statement on the ministers’ previous meeting on May 22 led with the same remark. A scan of MFA statements on meetings with other foreign ministers indicates the wording is not a matter of routine. The statement suggested that the Chinese government view is that it is incumbent on Australia to take the initiative to improve bilateral relations: It is hoped that the Australian side will meet the Chinese side halfway, take an objective view on China’s development, truly regards China’s development as an opportunity rather than a threat, and do more things that are conducive to enhancing mutual trust and cooperation between the two sides… The same statement asserted that Mr Wang reportedly told Ms Bishop, ‘The Chinese side has never interfered in the internal affairs of other countries and will never carry out the so-called infiltration in other countries.’ Following the meeting the PRC Foreign Minister told a press conference: [W]e hope that Australia can do more that is in the interest of increasing mutual trust between the two countries, and not be groundlessly suspicious.