Summary Report OPERATING and EVALUATING UNIVERSITY HUBS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign up Form

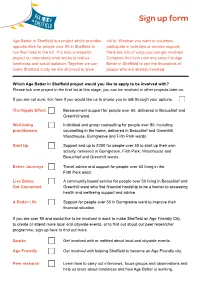

Sign up form Age Better in Sheffield is a project which provides old in. Whether you want to volunteer, opportunities for people over 50 in Sheffield to participate in activities or receive support, live their lives to the full. It is also a research there are lots of ways you can get involved. project to understand what works to reduce Complete this form now and send it to Age loneliness and social isolation. Together we can Better in Sheffield to join the thousands of make Sheffield a city we are all proud to grow people who are already involved. Which Age Better in Sheffield project would you like to apply to be involved with? Please tick one project in the first list at this stage, you can be involved in other projects later on. If you are not sure, tick here if you would like us to phone you to talk through your options. The Ripple Effect Bereavement support for people over 50, delivered in Beauchief and Greenhill ward. Well-being Individual and group counselling for people over 50, including practitioners counselling in the home, delivered in Beauchief and Greenhill, Woodhouse, Burngreave and Firth Park wards. Start Up Support and up to £200 for people over 50 to start up their own activity, delivered in Burngreave, Firth Park, Woodhouse and Beauchief and Greenhill wards. Better Journeys Travel advice and support for people over 50 living in the Firth Park ward. Live Better, A community based service for people over 50 living in Beauchief and Get Connected Greenhill ward who find financial hardship to be a barrier to accessing health and wellbeing support and advice. -

Christ Church Dore Newsletter May 2020

Christ Church Dore Newsletter May 2020 Walking Group Church Newsletter April 2020 The doors were locked, but Jesus came and stood among them and He said ‘Peace be We hope you are all well and, if allowed, are finding with you’. opportunities to perhaps do some walking? We are fortunate and are still able to enjoy a walk most John Chapter 20 v26 days but appreciate not everyone is in the same situation. For us an unexpected benefit of the current situation is that we have been exploring lots of the less used tracks around and across Blacka Moor, Totley Moor and Houndkirk Moor. We’ve plenty of ideas for new walks within a 5 minutes car journey from church, once lockdown is lifted! Another benefit has been paying much more attention to the progress of spring than usual. The woods are just bursting with life and it is great to hear in the church service chat rooms people swapping details of where to walk to find the best bluebells! With our love Online services every Sunday – check your emails and church web site for Hazel and David Sunday and mid week services. Previous online services are available on the church website. http://www.dorechurch.org.uk/services/ virtual-church-service In this period of lock down, days may seem the same but do not miss Friday 8th May is the 75th Anniversary of VE Day Thursday 21st May is Ascension Day Sunday 31st May is Pentecost 1 Signs of hope and thanks seen in and around Dore and Totley Do all the good you can. -

Agenda Item 3

Agenda Item 3 Minutes of the Meeting of the Council of the City of Sheffield held in the Council Chamber, Town Hall, Pinstone Street, Sheffield S1 2HH, on Wednesday 5 December 2012, at 2.00 pm, pursuant to notice duly given and Summonses duly served. PRESENT THE LORD MAYOR (Councillor John Campbell) THE DEPUTY LORD MAYOR (Councillor Vickie Priestley) 1 Arbourthorne Ward 10 Dore & Totley Ward 19 Mosborough Ward Julie Dore Keith Hill David Barker John Robson Joe Otten Isobel Bowler Jack Scott Colin Ross Tony Downing 2 Beauchiefl Greenhill Ward 11 East Ecclesfield Ward 20 Nether Edge Ward Simon Clement-Jones Garry Weatherall Anders Hanson Clive Skelton Steve Wilson Nikki Bond Roy Munn Joyce Wright 3 Beighton Ward 12 Ecclesall Ward 21 Richmond Ward Chris Rosling-Josephs Roger Davison John Campbell Ian Saunders Diana Stimely Martin Lawton Penny Baker Lynn Rooney 4 Birley Ward 13 Firth Park Ward 22 Shiregreen & Brightside Ward Denise Fox Alan Law Sioned-Mair Richards Bryan Lodge Chris Weldon Peter Price Karen McGowan Shelia Constance Peter Rippon 5 Broomhill Ward 14 Fulwood Ward 23 Southey Ward Shaffaq Mohammed Andrew Sangar Leigh Bramall Stuart Wattam Janice Sidebottom Tony Damms Jayne Dunn Sue Alston Gill Furniss 6 Burngreave Ward 15 Gleadless Valley Ward 24 Stannington Ward Jackie Drayton Cate McDonald David Baker Ibrar Hussain Tim Rippon Vickie Priestley Talib Hussain Steve Jones Katie Condliffe 7 Central Ward 16 Graves Park Ward 25 Stockbridge & Upper Don Ward Jillian Creasy Ian Auckland Alison Brelsford Mohammad Maroof Bob McCann Philip Wood Robert Murphy Richard Crowther 8 Crookes Ward 17 Hillsborough Ward 26 Walkey Ward Sylvia Anginotti Janet Bragg Ben Curran Geoff Smith Bob Johnson Nikki Sharpe Rob Frost George Lindars-Hammond Neale Gibson 9 Darnall Ward 18 Manor Castle Ward 27 West Ecclesfield Ward Harry Harpham Jenny Armstrong Trevor Bagshaw Mazher Iqbal Terry Fox Alf Meade Mary Lea Pat Midgley Adam Hurst 28 Woodhouse Ward Mick Rooney Jackie Satur Page 5 Page 6 Council 5.12.2012 1. -

Sheffield City Council Place Report to West and North

SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL PLACE REPORT TO WEST AND NORTH PLANNING AND DATE 31/08/2010 HIGHWAYS COMMITTEE REPORT OF DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT SERVICES ITEM SUBJECT APPLICATIONS UNDER VARIOUS ACTS/REGULATIONS SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS SEE RECOMMENDATIONS HEREIN THE BACKGROUND PAPERS ARE IN THE FILES IN RESPECT OF THE PLANNING APPLICATIONS NUMBERED. FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS N/A PARAGRAPHS CLEARED BY BACKGROUND PAPERS CONTACT POINT FOR ACCESS Vernon Faulkner TEL 0114 2734183 NO: AREA(S) AFFECTED CATEGORY OF REPORT OPEN 2 Application No. Location Page No. 10/02474/FUL 488 Redmires Road Sheffield 6 S10 4LG 10/02434/FUL Ewden Barn Bank Lane 12 Sheffield S36 3ZL 10/02110/FUL Chestnut Grove Curtilage Of 485 Loxley Road 18 Sheffield S6 6RP 10/01805/FUL 5 St Mark Road Sheffield 33 S36 2TF 10/01530/RG3 Land Between Buckenham Street Clun Street And 41 Ellesmere Road Sheffield 10/01372/FUL Storrs Farm, Storrs Lane And Broad Oak, Stopes Road 64 Sheffield S6 6GY 10/01225/FUL Site Of Clinical Psychology Unit Northern General Hospital 73 Herries Road Sheffield S5 7AU 10/01128/FUL 69 Norwood Road Sheffield 87 S5 7BP 3 10/01017/CHU 261 Ellesmere Road North And 163 Scott Road Sheffield 99 S4 7DP 4 5 SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL Report Of The Head Of Planning, Transport And Highways, Development, Environment And Leisure To The NORTH & WEST Planning And Highways Area Board Date Of Meeting: 31/08/2010 LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS FOR DECISION OR INFORMATION *NOTE* Under the heading “Representations” a Brief Summary of Representations received up to a week before the Area Board date is given (later representations will be reported verbally). -

Burngreave & Fir Vale

Burngreave & Fir Vale Summary of Evaluation Work SECTION ONE - BACKGROUND Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start programme was agreed December 2000. Staff were in post April 2001 services were delivered May/June 2001. AREA DESCRIPTION The Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start area is diverse and encompasses a range of different languages, cultures and religions. There is a transient population within the area which includes two Mother and Baby Units that take parents from outside of Sheffield and two Women’s Refuges. The area also houses the largest asylum seeking population in Sheffield. The area is a ‘New Deal For Communities’ area and is therefore seeing much regeneration. There are many new projects and schemes springing up, all seeking to recruit new workers and involve local people. The area suffers from poor media coverage due to gun crime and a drugs culture. The area has a negative image and services are struggling to recruit to the area. Since 2002 Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start programme has never been fully staffed and we have had to have agency staff for a number of services. Other services such as health services and New Deal are struggling to recruit to the area. The area is seen as a difficult area to work.. Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start programme is the largest in Sheffield being approved with 1049 under 4’s at the time - numbers are presently 1150. Although it is the largest programme in the city, Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start does not have the largest revenue budget or get the same amount of funding per child as other Sure Start programmes in the city. -

Rotherham Sheffield

S T E A D L To Penistone AN S NE H E LA E L E F I RR F 67 N Rainborough Park N O A A C F T E L R To Barnsley and I H 61 E N G W A L A E W D Doncaster A L W N ELL E I HILL ROAD T E L S D A T E E M R N W A R Y E O 67 O G O 1 L E O A R A L D M B N U E A D N E E R O E O Y N TH L I A A C N E A Tankersley N L L W T G N A P E O F A L L A A LA E N LA AL 6 T R N H C 16 FI S 6 E R N K Swinton W KL D 1 E BER A E T King’s Wood O M O 3 D O C O A 5 A H I S 67 OA A W R Ath-Upon-Dearne Y R T T W N R S E E E RR E W M Golf Course T LANE A CA 61 D A 6 A O CR L R R B E O E D O S A N A A S A O M L B R D AN E E L GREA Tankersley Park A CH AN AN A V R B ES L S E E D D TER L LDS N S R L E R R A R Y I E R L Golf Course O N O IE O 6 F O E W O O E 61 T A A F A L A A N K R D H E S E N L G P A R HA U L L E WT F AN B HOR O I E O E Y N S Y O E A L L H A L D E D VE 6 S N H 1 I L B O H H A UE W 6 S A BR O T O E H Finkle Street OK R L C EE F T O LA AN H N F E E L I E A L E A L N H I L D E O F Westwood Y THE River Don D K A E U A6 D H B 16 X ROA ILL AR S Y MANCHES Country Park ARLE RO E TE H W MO R O L WO R A N R E RT RT R H LA N E O CO Swinton Common N W A 1 N Junction 35a D E R D R O E M O A L DR AD O 6 L N A CL AN IV A A IN AYFIELD E OOBE E A A L L H R D A D S 67 NE LANE VI L E S CT L V D T O I H A L R R A E H YW E E I O N R E Kilnhurst A W O LI B I T D L E G G LANE A H O R D F R N O 6 R A O E N I O 2 Y Harley A 9 O Hood Hill ROAD K N E D D H W O R RTH Stocksbridge L C A O O TW R N A Plantation L WE R B O N H E U Y Wentworth A H L D H L C E L W A R E G O R L N E N A -

Population Estimates for Wards

Appendix C: 2011 Census Report 2: Population Estimates for Wards Introduction The 2011 Census was carried out by Office for National Statistics on 23 March 2011. All of the results relate to that date. As such, they do not compare with the mid‐year estimates for 2011 or for any of the previous years. One of the things that the Census has highlighted is the difference between the population on Census data and at the June mid‐year in a university city like Sheffield. Students are counted at their term time address, but by June many final year students have left the city whilst the first year students have not yet moved in. 2011 Census Report 1 summarised the first output from the 2011 Census, which set out the population estimates for local authorities. This report now looks at the population estimates for Sheffield wards, which were released by the Office for National Statistics on 23rd November 2012. Only the population age and sex breakdowns and household counts are published at present. Ethnicity and other data will be published in subsequent releases. (See 6 below on future releases) The report identifies: the changes in ward populations since 2001 the significant differences between the wards and the city averages the population in households and in communal establishments Ward Population Estimates Ward Size Around the time of the 2001 Census, the Boundary Commission were conducting a review of Sheffield’s wards. The review reported just too late for these to become the Census wards, but it did mean that there was not a large variation in population size between the 28 wards. -

Fxstandardukpublictimetables.Rpt

Stagecoach in Yorkshire Days of Operation MONDAY TO FRIDAY Commencing 7th March 2021 Service Number 088 Service Description Smithy Wood - Bents Green Service No. 88 88 88 88 88 88 788 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 Sch S Ecclesfield, Green Lane 0445 0534 0604 0634 0654 0714 - 0733 0752 0807 0820 0835 0846 0857 0909 0921 0932 0944 0956 1007 Firth Park, Sicey Avenue 0455 0544 0614 0644 0704 0724 - 0743 0802 0817 0831 0846 0857 0908 0920 0932 0943 0955 1007 1018 Burngreave Rd, Arnold Clark 0503 0552 0622 0652 0712 0732 - 0752 0811 0826 0840 0855 0906 0917 0929 0941 0952 1004 1016 1027 Sheffield, Snig Hill (In) CG9 0513 0602 0632 0702 0722 0742 0752 0802 0821 0836 0850 0905 0916 0927 0939 0951 1002 1014 1026 1037 Hunters Bar/Neill Road 0522 0611 0641 0711 0731 0751 0811 0811 0831 0846 0901 0916 0927 0939 0951 1003 1015 1027 1039 1051 Brincliffe, Lay-by 0525 0614 0644 0714 0734 0754 0815 0814 0834 0849 0904 0919 0931 0943 0955 1007 1019 1031 1043 1055 Opp High Storrs School - - - - - - 0817 - - - - - - - - - - - - - Service No. 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 Ecclesfield, Green Lane 1016 1028 1040 1052 1103 1114 1126 1138 1150 1202 1214 1226 1238 1250 1302 1315 1327 1339 1351 1403 Firth Park, Sicey Avenue 1027 1039 1051 1103 1114 1125 1137 1149 1201 1213 1225 1237 1249 1301 1313 1326 1338 1350 1402 1414 Burngreave Rd, Arnold Clark 1036 1048 1100 1112 1123 1134 1146 1158 1210 1222 1234 1246 1258 1310 1322 1335 1347 1359 1411 1423 Sheffield, Snig Hill (In) CG9 1046 1058 1110 1122 1133 1144 1156 1208 1220 1232 1244 1256 1308 1320 1332 1345 1357 1409 1421 1433 Hunters Bar/Neill Road 1102 1114 1126 1138 1150 1202 1214 1226 1238 1250 1302 1314 1326 1338 1350 1403 1415 1427 1439 1451 Brincliffe, Lay-by 1107 1119 1131 1143 1155 1207 1219 1231 1243 1255 1307 1319 1331 1343 1355 1407 1419 1431 1443 1455 Opp High Storrs School - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Service No. -

Community Connector

COMMUNITY The CONNECTOR A newsletter for people in Darnall, Tinsley, Attercliffe and Handsworth Welcome! We are excited to welcome you to the first edition of your local newsletter, covering homes in the Attercliffe, Darnall, Tinsley and Handsworth areas of Sheffield. A small group of local organisations have come together to work in partnership for the benefit of the community. We felt it important in these difficult times, to provide a space to share useful information, good new stories and help people connect to what is happening in their local area. If you have ideas for future editions, please get in touch with your suggestions to: [email protected] Welcome sign at High Hazels Park Enjoy! If you need a large print version of the newsletter, please contact us at the email address above, and we will provide one. This newsletter has been published and distributed thanks to funding from: Community Hub As your local Community Hub, Darnall Well Being are working closely with a range of services in the Darnall, Tinsley, Acres Hill and Handsworth areas to support the community during Covid-19. We can help you by offering: • A friendly chat • Signposting/sharing information • Help with sorting out access to food • Help with accessing medication • Reassurance about the best place to get help If you or someone you know would like support, please contact us by: Email: [email protected] or Phone: 0114 249 6315 or Text/Call: 07946 320 808 We will respond within one working day. If you need urgent help, you -

Burngreave New Deal for Communities and Line Managed by Activity Sheffield

active BURNGREAVE Sport & Physical Activity for Adults Intro The Active Burngreave Taskforce aims to encourage and support the people of Burngreave to be more physically active. The aim of this directory is to provide local information on sport and physical activity clubs, groups and activities in the Burngreave area. Did you know? On a local level, physical inactivity is estimated to be causing 41 premature deaths per year in the Burngreave area! But the good news is: You can significantly reduce this risk by doing the recommended minimum amount of physical activity to benefit health. That is: • 30 minutes of moderate exercise, 5 times a week for adults and • 60 minutes of moderate exercise, 7 times a week for children A wide range of activities can make up this activity including walking to school or the shops, gardening, sport, housework, dancing and cycling. Please note: All information is correct at the time of going to print. It is the responsibility of the parent / guardian to ensure that coaches are suitably qualified and police checked, prior to participating. Sheffield City Council cannot be held responsible for any accidents, injuries or loss that may occur whilst undertaking an activity. 2 Contents Aerobics 6 Gardening & Conservation 9 Badminton 6 Health Basketball 6 & Fitness 9 Bowls 6 Martial Arts 10 Chairobics 7 Running 10 Cricket 7 Social Groups 10 Dance 8 Walking 11 Disability Yoga 11 Groups 8 Football 8 3 Useful Local Contacts Michala Spacey Courtney Stirling Burngreave Sports Development Project Co-ordinator Centre -

Shoosmiths LLP 73 Sidney Street Sheffield S1 4RG.FH10

From Leeds t N P The North Inset S o Sheffield Supertram e J35 n te n o a d t l G s e S n d H t i n o P u w F r a t u A rd e rn e iv St r al t t Unit 3, Speedwell Works G S S a l f te e a d e 73 Sidney Street n h u S w r ShefSheffieldfield o M A Sheffield S1 4RG R a r til F Midland A633 r o da ur te o ni Tel: 03700 86 3000 - Fax: 03700 86 5601 r St va a M l S t S h e t S u f A629 DX: 14393 Manchester C h A61 f T n o l w k Email: [email protected] o B6071 r R B t et o t t e et a e trS S S r S d e l M t M18 r e S m Barnsley y d a M1 A629 til a A630 J37 E n d m h u a a r n Penistone A635 Doncaster A h r e S o r t t F Masbrough S o A628 ey h J36 ydn Rotherham S S d J2 Roa St ryss 3 A6109 Stocksbridge M1 ry t Ma d Granville M18 Ma S a A1(M) o Road A61 Rotherham A61 R F a Peak J34 s rm Wincobank A618 D n J34 J33 J32 u e c e R A57 B h u e d A630 r A6178 d s Q a s J31 m 4 R R Meadowhall SHEFFIELD A57 d Tinsley District Retford a l d Interchange J34 M1 l n L A631 Worksop u A61 a + n m J30 e A61 A619 d A623 A1 E Brightside A6109 Chesterfield Brinsworth A614 A6102 A6178 A631 Malin Bridge A60 + J29 + Valley A61 Centertainment A6101 A6135 M1 By Car From the M1 Northbound and Southbound Malin Bridge Newhall J33 Leave the M1 at Junction 33 following signs to Sheffield Pitsmoor (A57), continue along Sheffield Parkway until the Park Burngreave Attercliffe From Square roundabout (Junction 2). -

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town Cl740-Cl820

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town cl740-cl820 Neville Flavell PhD The Division of Adult Continuing Education University of Sheffield February 1996 Volume Two PART TWO THE GROWTH OF THE TOWN <2 6 ?- ti.«» *• 3 ^ 268 CHAPTER 14 EXPANSION FROM 1736 IGOSLING) TO 1771 (FAIRBANKS THE TOWN IN 1736 Sheffield in Gosling's 1736 plan was small and relatively compact. Apart from a few dozen houses across the River Dun at Bridgehouses and in the Wicker, and a similar number at Parkhill, the whole of the built-up area was within a 600 yard radius centred on the Old Church.1 Within that brief radius the most northerly development was that at Bower Lane (Gibraltar), and only a limited incursion had been made hitherto into Colson Crofts (the fields between West Bar and the river). On the western and north-western edges there had been development along Hollis Croft and White Croft, and to a lesser degree along Pea Croft and Lambert Knoll (Scotland). To the south-west the building on the western side of Coalpit Lane was over the boundary in Ecclesall, but still a recognisable part of the town.2 To the south the gardens and any buildings were largely confined by the Park wall which kept Alsop Fields free of dwellings except for the ingress along the northern part of Pond Lane. The Rivers Dun and Sheaf formed a natural barrier on the east and north-east, and the low-lying Ponds area to the south-east was not ideal for house construction.