Shedding Light on the Pseudophoenix Decline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pseudophoenix Sargentii (Buccaneer Palm)

Pseudophoenix sargentii (Buccaneer Palm) Pseudophoenix sargentii is an attractive small palm, resembling the royal palm but can be distinquised by its trunk which is more smooth and glossy.It is a solitary, monoecious palm. It holds an open crown of pinnate leaves which can measure up to 2 m long. In habitat, it is usually found along the coast in alkaline soil. The fruit is red, hence the common name ''cherry palm<span style="line-height:20.7999992370605px">''</span><span style="line- height:1.6em">.</span> Landscape Information French Name: Palmier de guinée Pronounciation: soo-doh-FEE-niks sar-JEN- tee-eye Plant Type: Palm Origin: South Florida, the Bahamas, Belize, Cuba Heat Zones: Hardiness Zones: 10, 11, 12 Uses: Specimen, Indoor, Container Size/Shape Growth Rate: Slow Tree Shape: Upright, Palm Canopy Symmetry: Symmetrical Canopy Density: Open Canopy Texture: Fine Height at Maturity: 8 to 15 m Spread at Maturity: 3 to 5 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 10 to 20 Years Plant Image Pseudophoenix sargentii (Buccaneer Palm) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Spiral Leaf Venation: Parallel Leaf Persistance: Evergreen Leaf Type: Odd Pinnately compund Leaf Blade: 50 - 80 Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Medium Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Flower Flower Showiness: True Flower Size Range: 0 - 1.5 Flower Type: Panicle Flower Sexuality: Monoecious (Bisexual) Flower Scent: Pleasant Flower Color: Green, Yellow Seasons: Year Round Trunk Trunk Has Crownshaft: True Plant Image Trunk -

Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Volume 52: 1-415 Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands Editors Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez and Mark T. Strong Department of Botany National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 2005 ABSTRACT Acevedo-Rodríguez, Pedro and Mark T. Strong. Monocots and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, volume 52: 415 pages (including 65 figures). The present treatment constitutes an updated revision for the monocotyledon and gymnosperm flora (excluding Orchidaceae and Poaceae) for the biogeographical region of Puerto Rico (including all islets and islands) and the Virgin Islands. With this contribution, we fill the last major gap in the flora of this region, since the dicotyledons have been previously revised. This volume recognizes 33 families, 118 genera, and 349 species of Monocots (excluding the Orchidaceae and Poaceae) and three families, three genera, and six species of gymnosperms. The Poaceae with an estimated 89 genera and 265 species, will be published in a separate volume at a later date. When Ackerman’s (1995) treatment of orchids (65 genera and 145 species) and the Poaceae are added to our account of monocots, the new total rises to 35 families, 272 genera and 759 species. The differences in number from Britton’s and Wilson’s (1926) treatment is attributed to changes in families, generic and species concepts, recent introductions, naturalization of introduced species and cultivars, exclusion of cultivated plants, misdeterminations, and discoveries of new taxa or new distributional records during the last seven decades. -

Pseudophoenix Sargentii) on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park

Status update: Long-term monitoring of Sargent’s cherry palm (Pseudophoenix sargentii) on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park FEBRUARY 2021 Acknowledgments Thank you to Biscayne National Park for more than three decades of support for this collaborative project on Pseudophoenix sargentii augmentation and demographic monitoring. Monitoring in 2021 was funded by the Florida Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, under Agreement #027132. For assistance with field work and logistics we would like to thank Morgan Wagner, Michael Hoffman, Brian Lockwood, Shelby Moneysmith, Vanessa McDonough, and Astrid Santini from Biscayne National Park, Eliza Gonzalez from Montgomery Botanical Center, Dallas Hazelton from Miami-Dade County, and volunteer biologists Joseph Montes de Oca and Elizabeth Wu. Thank you to the cooperators whose excellent past work on this project has laid the foundation upon which we stand today, especially Carol Lippincott, Rob Campbell, Joyce Maschinski, Janice Duquesnel, Dena Garvue, and Sam Wright. Janice Duquesnel provided important details about the 1991-1994 outplanting efforts. Suggested citation Possley, J., J. Lange, S. Wintergerst and L. Cuni. 2021. Status update: long-term monitoring of Pseudophoenix sargentii on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park. Unpublished report from Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, funded by Florida Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services Agreement #027132. Background Pseudophoenix sargentii H.Wendl. ex Sarg., known by the common names ‘Sargent’s cherry palm’ and ‘buccaneer palm,’ is a slow-growing palm native to coastal habitats throughout the Caribbean basin, where it grows on exposed limestone or in humus or sand over limestone. Over the past century, the species has declined throughout its range, due to in part to overharvesting for use in landscaping. -

A Preliminary List of the Vascular Plants and Wildlife at the Village Of

A Floristic Evaluation of the Natural Plant Communities and Grounds Occurring at The Key West Botanical Garden, Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida Steven W. Woodmansee [email protected] January 20, 2006 Submitted by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue, Miami, Florida 33170 George D. Gann, Executive Director Submitted to CarolAnn Sharkey Key West Botanical Garden 5210 College Road Key West, Florida 33040 and Kate Marks Heritage Preservation 1012 14th Street, NW, Suite 1200 Washington DC 20005 Introduction The Key West Botanical Garden (KWBG) is located at 5210 College Road on Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida. It is a 7.5 acre conservation area, owned by the City of Key West. The KWBG requested that The Institute for Regional Conservation (IRC) conduct a floristic evaluation of its natural areas and grounds and to provide recommendations. Study Design On August 9-10, 2005 an inventory of all vascular plants was conducted at the KWBG. All areas of the KWBG were visited, including the newly acquired property to the south. Special attention was paid toward the remnant natural habitats. A preliminary plant list was established. Plant taxonomy generally follows Wunderlin (1998) and Bailey et al. (1976). Results Five distinct habitats were recorded for the KWBG. Two of which are human altered and are artificial being classified as developed upland and modified wetland. In addition, three natural habitats are found at the KWBG. They are coastal berm (here termed buttonwood hammock), rockland hammock, and tidal swamp habitats. Developed and Modified Habitats Garden and Developed Upland Areas The developed upland portions include the maintained garden areas as well as the cleared parking areas, building edges, and paths. -

Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae

horticulturae Review Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae Diego Gutiérrez del Pozo 1, José Javier Martín-Gómez 2 , Ángel Tocino 3 and Emilio Cervantes 2,* 1 Departamento de Conservación y Manejo de Vida Silvestre (CYMVIS), Universidad Estatal Amazónica (UEA), Carretera Tena a Puyo Km. 44, Napo EC-150950, Ecuador; [email protected] 2 IRNASA-CSIC, Cordel de Merinas 40, E-37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Matemáticas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Salamanca, Plaza de la Merced 1–4, 37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-923219606 Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 2 October 2020; Published: 7 October 2020 Abstract: Fruit and seed shape are important characteristics in taxonomy providing information on ecological, nutritional, and developmental aspects, but their application requires quantification. We propose a method for seed shape quantification based on the comparison of the bi-dimensional images of the seeds with geometric figures. J index is the percent of similarity of a seed image with a figure taken as a model. Models in shape quantification include geometrical figures (circle, ellipse, oval ::: ) and their derivatives, as well as other figures obtained as geometric representations of algebraic equations. The analysis is based on three sources: Published work, images available on the Internet, and seeds collected or stored in our collections. Some of the models here described are applied for the first time in seed morphology, like the superellipses, a group of bidimensional figures that represent well seed shape in species of the Calamoideae and Phoenix canariensis Hort. ex Chabaud. -

Table of Contents Than a Proper TIMOTHY K

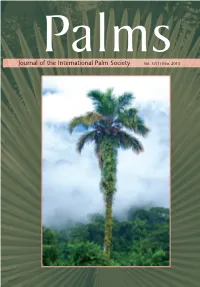

Palms Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 57(1) Mar. 2013 PALMS Vol. 57(1) 2013 CONTENTS Island Hopping for Palms in Features 5 Micronesia D.R. H ODEL Palm News 4 Palm Literature 36 Shedding Light on the 24 Pseudophoenix Decline S. E DELMAN & J. R ICHARDS An Anatomical Character to 30 Support the Cohesive Unit of Butia Species C. M ARTEL , L. N OBLICK & F.W. S TAUFFER Phoenix dactylifera and P. sylvestris 37 in Northwestern India: A Glimpse of their Complex Relationships C. N EWTON , M. G ROS -B ALTHAZARD , S. I VORRA , L. PARADIS , J.-C. P INTAUD & J.-F. T ERRAL FRONT COVER A mighty Metroxylon amicarum , heavily laden with fruits and festooned with epiphytic ferns, mosses, algae and other plants, emerges from the low-hanging clouds near Nankurupwung in Nett, Pohnpei. See article by D.R. Hodel, p. 5. Photo by D.R. Hodel. The fruits of Pinanga insignis are arranged dichotomously BACK COVER and ripen from red to Hydriastele palauensis is a tall, slender palm with a whitish purplish black. See article by crownshaft supporting the distinctive canopy. See article by D.R. Hodel, p. 5. Photo by D.R. Hodel, p. 5. Photo by D.R. Hodel . D.R. Hodel. 3 PALMS Vol. 57(1) 2013 PALM NEWS Last year, the South American Palm Weevil ( Rhynchophorus palmarum ) was found during a survey of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, Texas . This palm-killing weevil has caused extensive damage in other parts of the world, according to Dr. Raul Villanueva, an entomologist at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at Weslaco. -

Review the Conservation Status of West Indian Palms (Arecaceae)

Oryx Vol 41 No 3 July 2007 Review The conservation status of West Indian palms (Arecaceae) Scott Zona, Rau´l Verdecia, Angela Leiva Sa´nchez, Carl E. Lewis and Mike Maunder Abstract The conservation status of 134 species, sub- ex situ and in situ conservation projects in the region’s species and varieties of West Indian palms (Arecaceae) botanical gardens. We recommend that preliminary is assessed and reviewed, based on field studies and conservation assessments be made of the 25 Data current literature. We find that 90% of the palm taxa of Deficient taxa so that conservation measures can be the West Indies are endemic. Using the IUCN Red List implemented for those facing imminent threats. categories one species is categorized as Extinct, 11 taxa as Critically Endangered, 19 as Endangered, and 21 as Keywords Arecaceae, Caribbean, Palmae, palms, Red Vulnerable. Fifty-seven taxa are classified as Least List, West Indies. Concern. Twenty-five taxa are Data Deficient, an indica- tion that additional field studies are urgently needed. The 11 Critically Endangered taxa warrant immediate This paper contains supplementary material that can conservation action; some are currently the subject of only be found online at http://journals.cambridge.org Introduction Recent phylogenetic work has changed the status of one genus formerly regarded as endemic: Gastrococos is now The islands of the West Indies (the Caribbean Islands shown to be part of the widespread genus Acrocomia sensu Smith et al., 2004), comprising the Greater and (Gunn, 2004). Taking these changes into consideration, Lesser Antilles, along with the Bahamas Archipelago, endemism at the generic level is 14%. -

Cyclura Cychlura) in the Exuma Islands, with a Dietary Review of Rock Iguanas (Genus Cyclura)

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 11(Monograph 6):121–138. Submitted: 15 September 2014; Accepted: 12 November 2015; Published: 12 June 2016. FOOD HABITS OF NORTHERN BAHAMIAN ROCK IGUANAS (CYCLURA CYCHLURA) IN THE EXUMA ISLANDS, WITH A DIETARY REVIEW OF ROCK IGUANAS (GENUS CYCLURA) KIRSTEN N. HINES 3109 Grand Ave #619, Coconut Grove, Florida 33133, USA e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—This study examined the natural diet of Northern Bahamian Rock Iguanas (Cyclura cychlura) in the Exuma Islands. The diet of Cyclura cychlura in the Exumas, based on fecal samples (scat), encompassed 74 food items, mainly plants but also animal matter, algae, soil, and rocks. This diet can be characterized overall as diverse. However, within this otherwise broad diet, only nine plant species occurred in more than 5% of the samples, indicating that the iguanas concentrate feeding on a relatively narrow core diet. These nine core foods were widely represented in the samples across years, seasons, and islands. A greater variety of plants were consumed in the dry season than in the wet season. There were significant differences in parts of plants eaten in dry season versus wet season for six of the nine core plants. Animal matter occurred in nearly 7% of samples. Supported by observations of active hunting, this result suggests that consumption of animal matter may be more important than previously appreciated. A synthesis of published information on food habits suggests that these results apply generally to all extant Cyclura species, although differing in composition of core and overall diets. Key Words.—Bahamas; Caribbean; carnivory; diet; herbivory; predation; West Indian Rock Iguanas INTRODUCTION versus food eaten in unaffected areas on the same island, finding differences in both diet and behavior (Hines Northern Bahamian Rock Iguanas (Cyclura cychlura) 2011). -

Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 46(1) March 2002

Journalof the InternationalPalm Society Vol.46(1) March 2002 THE INTERNATIONATPAIM SOCIETY,INC. The International Palm Society Palms(rormerrv o*')Fili?.,"" Journalof The Internation, An illustrated,peer-reviewed quarterly devoted to " informationabout palms and publishedin March,June, ffitt'# **,,,*,,nI:#.*g'i,.*r:r"'" Seotember and Decemberbv The lnternationalPalm nationalin scopewith worldwidemembership, and the formationof regionalor localchapters affiliated with the internationalroii"ty ir "n.ourug.i. Pleaseaddress all inquiriesregarding membership or informationabout Editors: Dransfield,Herbarium, Royal Botanic The-lnternationaiPalm Society Inc., P.O. :::i:ff:*::::lohn :::,I.^, -. "l, the socieryio -il;;;;k;;, Ri;;;;";, s,,i"y,r,ve :hi, u;t;J Kansas 660 44'88e7' usA' Kingdom,e-mail [email protected], tel.44- 181-332-5225,Fax 44-1 B1 -332-5278. lrr,itiJr,"-rence' ScottZona, Fairchild Tropical Carden, 11935 Old Cutler /310tuhburn' nou"on',., Road,Coral Cables (Miami), Florida 33156, USA, e-mail ?J#*;:, I!X':.:;:ii c'm'e'[email protected]. 1 -105-66l-1 65i ext. ;::r":ff::;;:;:ffi l1]l.l-'..*"'::;:';,^, 467Mann Library, y;fji#; 1485 3'U sA"e. ma i' lii:1L?,ililii :ii:fl 1,. "' I,lii,%S?l,:iixk l'[i: i :]?:,1?:i ":;ffi [l;1;l', ) 2418 S ta ffo rd s p ri n qs' [email protected]?li'ijffi tel. 61;, -7-3800-5526.l:,",:*i,ii ;tli i:l$i"il;* :i t'#,",lif T ffiil *i**i"*' rt;d;;;:' ^"* i:-::,',:"'ffil # ;,::'; :::"",, " :::,T:::::"",.i;.1i1,,ffi::::"672e Peac.ck ::1:::"".';J:::;::::ll.n, ** pu ". fi8fl3;'.?i3l,i'i; li:i'!:,' X:,1: ;l,lt; 8il' il'[f,,xl:,'.n"J,?:}#il',*"d:,:il;:, Treasurer: HowardWaddell, 6120 SW132 St.,Miami, OldCutler Road, Coral Cables (Miami), Florida 33156, sA,e-mai I hwaddell@prod isy.net, tel. -

I. Pseudophoenix Lediniana Read, Sp. Nov. Type: R. W. Read 6·' F

1968] Read: A Study of PSEUDOPHOENIX 189 2. Pseudopedicels of the perfect flowers and of the fruits less than 4 mm. long; endocarp 13-17 mm. in diam.; pinnae lacking scales within basal fold. Hispaniola __ 1. P. Ledinialla 2. Pseudopedicels of the perfect flowers and of the fruits more than 4 mm. long; endo carp less than 12 mm. in diam.; pinnae with scales within the basal fold. 3. Stamen filaments less than 1.5 mm. long', not united at their bases to form a cupule. Hispaniola _. 3. P. Ekmallii 3. Stamen filaments mOre than 2 mm. long, united at their bases to form a cupule __________________________________ 4. P. Sarge" til 4. Inflorescence less tban 1,6 as long as the leaves, erect in fruit; primary hract less than % as long as the peduncle. Florida, Mexico, British Honduras __ _____________________________________ __ 4A. P. Sargentii subsp. Sargentii 4. Inflorescence more than ¥j as long as the leaves, pendulous from an arcuate peduncle in fruit; primary hract more than :y, as long as the peduncle __ ___________________________________________ __ 4B. P. Sargentii subsp. saollae 5. Leaves gray·green below; fruit globular or subpyriform, less than 1.5 cm. in diarTI. Hispaniola, Saona, La Gonavc, Cuba, Bahama Islands _ ______________________________________ __ 4Ba. P. Sargentii subsp_ saonae val'. saol1ae 5. Leaves white or silvery below; fruit ovoid, more than 1.5 em. in diam. Navassa . 4Bb. P. S'ngentii subsp. saonae val'. navassa"a I. Pseudophoenix Lediniana Read, sp. nov. Type: R. W. Read 6·' F. Pierre Louis 1154 (BH, holotype; FTG, isotype). -

Raoiella Indica Global Invasive Species Database (GISD)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Raoiella indica Raoiella indica System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Arthropoda Arachnida Acariformes Tenuipalpidae Common name red palm mite (English), coconut red mite (English), coconut mite (English), red date mite (English), scarlet mite (English), frond crimson mite (English), leaflet false spider mite (English) Synonym Similar species Tetranychus Summary Raoiella indica (the red palm mite) is a parasitic mite invasive in the Caribbean region; it poses a serious threat to many plant industries. Its recent invasion is referred to as the biggest mite explosion in the Americas. Already taking serious tolls on coconut, ornamental palm and orchid crops, its infestation of new species and spread to new locations makes it one the most menacing pests to the Western tropics. view this species on IUCN Red List Species Description Raoiella indica is a bright red mite that parasitizes many important plant species, principally palm and banana species. It can be found on the undersides of their leaves. R. indica resembles the common pests spider mites (Family:Tetranychidae) only with longer spatulate setae and lacking their web spinning ability. Adult females are about 0.32mm long and have dark patches on their abdomen. They are larger than males which have more triangular abdomens. Nymphal stages look similar only smaller with less pronounced setae. The mites are visible with the naked eye and usually congregate in clusters of 100-300, and are surrounded by their white exuvial remains (cast skins). (Kane, 2006; Welbourn, 2007). Lifecycle Stages Eggs are atteched to leaves by a stipe and hatch after an average of 6.5 days. -

Botanic Garden Metacollection

TOWARD THE METACOLLECTION: Coordinating conservation collections to safeguard plant diversity Patrick Griffith/Montgomery Botanical Center Botanic gardens hold amazing plant diversity, such as these palms at Montgomery Botanical Center – connecting and coordinating living THE LARGEST FORCE FOR collections together finds new benefits for conservation. PLANT CONSERVATION A single plant grown at a garden can contribute to conservation, but it takes many plants to capture sufficient genetic diversity and thus truly safeguard species for the long term. So, gardens might Worldwide, over 3,000 botanic gardens ask, “Which plants should I grow, and how many?” maintain at least one-third of all known Garden conservation science applied to real-world scenarios shows how vital our garden networks are to safeguarding plant plant diversity. The collective conservation biodiversity. A close look at the genetics of collections of power of botanic gardens is essential to exceptional plant species1 – and how they are networked among multiple botanic gardens – brings new insight into how gardens stop plant extinction. Networks allow are doing at present and how they can do better in the future. gardens to coordinate efforts to save Here we present recent discoveries and recommendations for endangered plants. The global web of capturing and maintaining diversity in a plant collection, and botanic gardens is the world’s largest describe how to leverage a network of such collections to advance conservation. We introduce and illustrate the force for plant conservation – as long as METACOLLECTION concept, with examples at different scales, it is well coordinated! provide an overview of sampling strategy for capturing diversity, and provide examples of how gardens can leverage methods developed by the zoo community to collectively manage conservation collections.