View Excerpt (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Randolph Bourne on Education

Randolph Bourne on education Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Horsman, Susan Alice, 1937- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 18:30:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/317858 RANDOLPH BOURNE ON EDUCATION by Susam Horsmam A Thesis Submitted t© the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the.Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE. UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 5 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library0 Brief quotations from this, thesis are al lowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended.quotation from or re production of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below? . J. -

Self-Portraiture in Borrow and the Powys

— 1 — Published in la lettre powysienne numéro 5, printemps 2003, see : http://www.powys-lannion.net/Powys/LettrePowysienne/number5.htm Stonehenge Leaving the bridge I ascended a gentle declivity, and presently reached what appeared to be a tract of moory undulating ground. It was now tolerably light, but there was a mist or haze abroad which prevented my seeing objects with much precision. I felt chill in the damp air of the early morn, and walked rapidly forward. In about half an hour I arrived where the road divided into two at an angle or tongue of dark green sward. “To the right or the left?” said I, and forthwith took, without knowing why, the left-hand road, along which I proceeded about a hundred yards, when, in the midst of the tongue or sward formed by the two roads, collaterately with myself, I perceived what I at first conceived to be a small grove of blighted trunks of oaks, barked and grey. I stood still for a moment, and then, turning off the road, advanced slowly towards it over the sward; as I drew nearer, I perceived that the objects which had attracted my curiosity, and which formed a kind of circle, were not trees, but immense upright stones. A thrill pervaded my system; just before me were two, the mightiest of the whole, tall as the stems of proud oaks, supporting on their tops a huge transverse stone, and forming a wonderful doorway. I knew now where I was, and laying down my stick and bundle, and taking off my hat, I advanced slowly, and cast myself — it was folly, perhaps, but I could not help what I did — cast myself, with my face on the dewy earth, in the middle of the portal of giants, beneath the transverse stone. -

Ankenym Powysjournal 1996

Powys Journal, 1996, vol. 6, pp. 7-61. ISSN: 0962-7057 http://www.powys-society.org/ http://www.powys-society.org/The%20Powys%20Society%20-%20Journal.htm © 1996 Powys Society. All rights reserved. Drawing of John Cowper Powys by Ivan Opffer, 1920 MELVON L. ANKENY Lloyd Emerson Siberell, Powys 'Bibliomaniac' and 'Extravagantic' John Cowper Powys referred to him as 'a "character", if you catch my meaning, this good Emerson Lloyd S. — a very resolute chap (with a grand job in a big office) & a swarthy black- haired black-coated Connoisseur air, as a Missioner of a guileless culture, but I fancy no fool in his office or in the bosom of his family!'1 and would later describe him as 'a grand stand-by & yet what an Extravagantic on his own our great Siberell is for now and for always!'2 Lloyd Emerson Siberell, the 'Extravagantic' from the midwestern United States, had a lifelong fascination and enthusiasm for the Powys family and in pursuit of his avocations as magazine editor, publisher, writer, critic, literary agent, collector, and corresponding friend was a constant voice championing the Powys cause for over thirty years. Sometimes over-zealous, always persistent, unfailingly solicitous, both utilized and ignored, he served the family faithfully as an American champion of their art. He was born on 18 September 1905 and spent his early years in the small town of Kingston, Ohio; 'a wide place in the road, on the fringe of the beautiful Pickaway plains the heart of Ohio's farming region, at the back door of the country, so to speak.' In his high school days he 'was always too busy reading the books [he] liked and playing truant to ever study seriously...' He 'enjoyed life' and was 'a voracious reader but conversely not the bookworm type of man.'3 At seventeen he left school and worked a year at the Mead Corporation paper mill in Chillicothe, Ohio and from this experience he dated his interest in the art and craft of paper and paper making. -

Open, Yet Missed the Powyses, John Cowper and Autobiography in Paradoxically Enigmatic Figure

Powys Notes CONTENTS the semiannual journal and newsletter of the In This Issue 4 Powys Society of North America Powys's Alien Story: Travelling, Speaking, Writing BEN JONES 5 Editor: "The People We Have Been": Denis Lane Notes on Childhood in Powys's Autobioqraphy A. THOMAS SOOTHWICK 13 Editorial Board: Friendships: John Cowper Powys, Llewelyn Powys, and Alyse Gregory Ben Jones, Carleton University HILDEGARDE LASELL WATSON 17 Peter Powys Grey, To Turn and Re-Turn: New York A review of Mary Casey, The Kingfisher1s Wing Richard Maxwell, CHARLES LOCK 24 Valparaiso University Editor's Notes 27 Charles Lock, University of Toronto Editorial Address: * * * 1 West Place, Chappaqua, N.Y. 10514 Subscription: THE POWYS SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA $10.00 U.S. ($12.00 Can.) for two issues; includes membership in PSNA Founded in December, 1983, the Powys Society of North America seeks to promote the study and Subscription Addresses: appreciation of the literary works of the Powys In the U.S.: InCanada: family, especially those of JOHN COWPER POWYS Richard Maxwell Ben Jones (1872-1963), T. F. POWYS (1875-1953), and LLEWELYN Department of English Department of English POWYS (1884-1939). Valparaiso University Carleton University Valparaiso, IN 46383 Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 5B6 The Society takes a special interest in the North American connections and experiences of the Powyses, and encourages the exploration of the extensive POWYS NOTES, Vol- 5, No* 1: Spring, 1989. (c) , 1989, The Powys collections of Powys material in North America and the Society of North America. Quotations from the works of John involvement, particularly of John Cowper and Llewelyn, Cowper Powys and T. -

Powys Society Newsletter 14: November 1991

Editorial At a time of recession, when many literary societies are losing members and the world of publishing is becoming ever more constrained, it is pleasing to see that the Powys Society is not only growing but extending into new and exciting areas. 1991 has seen not only an extremely successful Conference at Kingston Maurward, but also the establishment of a Powys display at Montacute House and a very popular exhibition of Powys materials at the Dorset County Museum. Linked to the exhibition was the publication by the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society of The Powys Family in Dorset, a pamphlet by Charles Lock based upon original research for his forthcoming biography of John Cowper Powys. The Society itself has also been active in the field of publishing, having launched the magnificent Powys Journal, 152 pages of unpublished Powys material, scholarly essays and review articles. The Journal is a major advance for the Society and one which will be valued by all of those with an interest in Powys studies, whether members of the Society or not. At the same time, the Society published a series of four postcards featuring photographs of Theodore, Llewelyn, John Cowper and the whole Powys family, as well as Alan Howe’s Powys Checklist, a thorough guide to the publications of each member of the family which will rapidly become indispensible to readers, collectors and students. Meanwhile, in addition to those forthcoming books already announced in the Newsletter, Gerald Pollinger, literary agent for the Powys family, reports that B.B.C television has shown interest in producing Weymouth Sands in 1993, while Central Television are considering the possibility of a film of Wolf Solent and the film options for A Glastonbury Romance and After My Fashion have been renewed. -

Opening Article Is an Edition of Her Journals 1923-48 (1973)

The Powys Review NUMBER EIGHT Angus Wilson SETTING THE WORLD ON FIRE "A very distinguished novel ... It is superb entertain- ment and social criticism but it is also a poem about the life of human beings - a moving and disturbing book and a very superior piece of art.'' Anthony Burgess, Observer "Wonderfully intricate and haunting new novel. The complex relationships between art and reality . are explored with a mixture of elegance, panache and concern that is peculiarly his ... magnificent." Margaret Drabble, Listener "As much for the truth and pathos of its central relation- ships as for the brilliance of the grotesques who sur- round them, I found Setting the World on Fire the most successful Wilson novel since Late Call. I enjoyed it very much indeed.'' Michael Ratcliffe, The Times "A novel which will give much pleasure and which exemplifies the civilised standards it aims to defend." Thomas Hinde, Sunday Telegraph "A book which I admire very much . this is an immensely civilised novel, life enhancing, with wonder- fully satirical moments.'' David Holloway, Daily Telegraph "... an exceptionally rich work . the book is witty, complex and frightening, as well as beautifully written.'' Isobel Murray, Financial Times Cover: Mary Cowper Powys with (1. to r.) Llewelyn, Marian and Philippa, c. 1886. The Powys Review Editor Belinda Humfrey Reviews Editor Peter Miles Advisory Board Glen Cavaliero Ben Jones Derrick Stephens Correspondence, contributions, and books for review may be addressed to the Editor, Department of English, Saint David's University College, Lampeter, Dyfed, SA48 7ED Copyright ©, The Editor The Powys Review is published with the financial support of the Welsh Arts Council. -

Glastonbury Companion

John Cowper Powys’s A Glastonbury Romance: A Reader’s Companion Updated and Expanded Edition W. J. Keith December 2010 . “Reader’s Companions” by Prof. W.J. Keith to other Powys works are available at: http://www.powys-lannion.net/Powys/Keith/Companions.htm Preface The aim of this list is to provide background information that will enrich a reading of Powys’s novel/ romance. It glosses biblical, literary and other allusions, identifies quotations, explains geographical and historical references, and offers any commentary that may throw light on the more complex aspects of the text. Biblical citations are from the Authorized (King James) Version. (When any quotation is involved, the passage is listed under the first word even if it is “a” or “the”.) References are to the first edition of A Glastonbury Romance, but I follow G. Wilson Knight’s admirable example in including the equivalent page-numbers of the 1955 Macdonald edition (which are also those of the 1975 Picador edition), here in square brackets. Cuts were made in the latter edition, mainly in the “Wookey Hole” chapter as a result of the libel action of 1934. References to JCP’s works published in his lifetime are not listed in “Works Cited” but are also to first editions (see the Powys Society’s Checklist) or to reprints reproducing the original pagination, with the following exceptions: Wolf Solent (London: Macdonald, 1961), Weymouth Sands (London: Macdonald, 1963), Maiden Castle (ed. Ian Hughes. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1990), Psychoanalysis and Morality (London: Village Press, 1975), The Owl, the Duck and – Miss Rowe! Miss Rowe! (London: Village Press, 1975), and A Philosophy of Solitude, in which the first English edition is used. -

Limestone and the Literary Imagination: a World-Ecological Comparison of John Cowper Powys and Kamau Brathwaite

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Limestone and the literary imagination: a world-ecological comparison of John Cowper Powys and Kamau Brathwaite AUTHORS Campbell, C JOURNAL Powys Journal DEPOSITED IN ORE 03 April 2020 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/120529 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication The Powys Journal XXX (2020) “Limestone and the Literary Imagination: a world-ecological comparison of John Cowper Powys and Kamau Brathwaite” Chris Campbell, University of Exeter This paper represents an attempt to think through some of the connections – concrete and abstracted -- between the work of the Powyses, Caribbean literature, and world literary theory. It affords a chance to test out some theoretical approaches for reading literature of the English South West (often typified as local, provincial or even parochial) within a global, environmental framework. To begin, I want to introduce some of the salient features of world-ecological literary comparison: first, by recalling the most important and empirical textual link between the world of the Powyses and the Caribbean region (focussing in on Llewelyn Powys’s perception of the connections between the islands of Portland and Barbados); and then, by bringing into fuller dialogue the work of John Cowper Powys with that of Bajan poet and historian Kamau Brathwaite. I suggest that this pairing of authors opens up new ways of reading literary works and also produces new ways of comprehending the connected ecologies of the limestone formations of South Dorset (Portland’s quarries, say, or the chalk downland of the ridgeway and Maiden Castle) with the coral capped limestone outcrops of the Eastern Caribbean. -

Historic Library & Rare Book

HISTORIC LIBRARY & RARE BOOK COLLECTION SHERBORNE SCHOOL THE POWYS LIBRARY Albert Reginald POWYS (1881-1936). Bor The Green (c) 1895-1899. A.R. Powys, Repair of Ancient Buildings (J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1929) A.R. Powys, From the Ground Up: Collected Papers of A.R. Powys. With an introduction by John Cowper Powys (JM Dent & Sons Ltd., 1937). A.R. Powys, The English House (The Powys Society, 1992). John Cowper POWYS (1872-1963). Wildman’s House (Mapperty) 1886-1891. John Cowper Powys, After My Fashion (London, Pan Books Ltd., 1980). John Cowper Powys, All or Nothing (London, Macdonald, 1960). John Cowper Powys, All or Nothing (London, Village Press, 1973). Presented to Sherborne School Library by M.R. Meadmore, April 1984. John Cowper Powys, Autobiography (London, Macdonald, 1967). With an introduction by J.B. Priestley. John Cowper Powys, The Brazen Head (London, Macdonald, 1969). John Cowper Powys, In Defence of Sensuality (London, Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1930). John Cowper Powys, The Diary of John Cowper Powys 1931 (London, Jeffrey Kwintner, 1990). John Cowper Powys, Dorothy M. Richardson (London, Village Press, 1974). Presented to Sherborne School Library by Gerald Pollinger, September 1977. John Cowper Powys, Dostoievsky (London, John Lane The Bodley Head, 1946). John Cowper Powys, Ducdame (London, Village Press, 1974). John Cowper Powys, A Glastonbury Romance (London, Macdonald, 1966). John Cowper Powys, Homer and the Aether (London, Macdonald, 1959). Presented to Sherborne School Library by Gerald Pollinger, September 1977. John Cowper Powys, The Inmates (London, Village Press, 1974). Presented to Sherborne School Library by M.R. Meadmore, April 1984. John Cowper Powys, In Spite of. -

Powys Society Newsletter 90, March 2017

Editorial Our back cover showing the Prophet Elijah smiting a priest of Baal (3 Kings 18, 40) il- lustrates Patrick Quigley’s account of Llewelyn Powys and Alyse’s journey to Palestine Llewelyn’s philosophy. Our December meeting discussed TFP’s friendship with Liam O’Flaherty and the Pro- gressive Bookshop, and the world of cruelty and hypocrisy in Mr. Tasker’s Gods, a book O’Flaherty greatly admired. T.F. Powys calls up very different responses, from those who see his world as controlled by demons of cruelty, and those who see their opposite, the besieged forces of light, innocence and kindness. Michael Kowalewski’s review in NL89, of Zouheir Jamoussi’s book on Theodore, emphasised the darkness and the role of an ‘Old Testament’ God of wrath. Ian Robinson, long-term publisher of TFP with the Brynmill Press, is of the party of the angels, and the long-suffering meek who are rewarded. TFP’s publisher Charles Prentice introduced the 1947 collection of stories, curiously named (by TF himself?) God’s Eyes A-Twinkle; and Glen Cavaliero’s poem imagines TFP sleeping beside, and in, the Map- powder churchyard. Nature, and seasons, were crucial to all the Powyses, and John Cowper’s years in up- state New York gave him sustained time to observe American skies, especially at sunrise. New books by our President (Collected Poems) and our Chairman (Figurative Painting) are reviewed. We have notes on JCP and music and on Alyse Gregory’s revised birth date. Members in Norfolk and New York visit two bookshops called after JCP’s late novel The Brazen Head. -

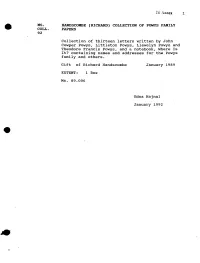

MS. Collection of Thirteen Letters Written by John Cowper Powys

21] Annex 1 MS. HANDSCOMBE (RICHARD) COLLECTION OF POWYS FAMILY COLL. PAPERS 92 Collection of thirteen letters written by John Cowper Powys, Littleton Powys, Llewelyn Powys and Theodore Francis Powys, and a notebook, Where Is It? containing names and addresses for the Powys family and others. Gift of Richard Handscombe January 1989 EXTENT: 1 Box Ms. 89.006 Edna Hajnal January 1992 2 MS. HANDSCOMBE (RICHARD) COLLECTION OF POWYS FAMILY COLL. PAPERS 92 CONTAINER LIST BoxPowys, John Cowper, Dorchester, Dorset, to My Dear 1 Sir. October 25, 1934. A.L.S. Folder 1 leaf. writes that Mr. Lahr is the only bookseller who would "just exactly meet your need", and gives his address. Powys, John Cowper, Dorchester, Dorset, to William F. Huber, Lakewood, Ohio. February 16, 1935. A.L.S. Folder 2 leaves. With envelope. writes that he is enclosing on the reverse page his name and thanks him for writing. Powys, John Cowper, Corwen, North Wales, to Ellis D. Robb, Atlanta, Georgia. February 17, 1936. A.L.S. Folder 1 leaf. with envelope. Thanks him for· sending review by Prof. Drewry and for asking about his health. Powys, John Cowper, Corwen, North Wales to Paul Williams, June 17, 1941. A.L.S. 3 folders. Comments on his health, the medicine and remedies he takes,and his diet. "Then comes my grand pleasure sensual greedy-gut daily delight & joy -- my supreme pleasure & satisfaction of the day ... i.e. 2 tea spoonfuls of tea in A smallish tea-pot a black kettle boiling on the fire close at hand if possible in the kitchen where I always have my happiest meal i.e breakfast as much sugar as I can get--.. -

Katharine Susan Anthony and the Birth of Modern Feminist Biography, 1877-1929

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Féminisme Oblige: Katharine Susan Anthony and the Birth of Modern Feminist Biography, 1877-1929 Anna C. Simonson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1992 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Féminisme Oblige: Katharine Susan Anthony and the Birth of Modern Feminist Biography, 1877-1929 by Anna Simonson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 ANNA SIMONSON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Nasaw Date Chair of Examining Committee Helena Rosenblatt Date Executive Officer Kathleen D. McCarthy Blanche Wiesen Cook Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Féminisme Oblige: Katharine Susan Anthony and the Birth of Modern Feminist Biography, 1877-1929 By Anna Simonson Advisor: David Nasaw Féminisme Oblige examines the life and work of Katharine Susan Anthony (1877-1965), a feminist, socialist, and pacifist whose early publications on working mothers (Mothers Who Must Earn [1914]) and women’s movements in Europe (Feminism in Germany and Scandinavia [1915]) presaged her final chosen vocation as a feminist biographer.