Light up the Darkness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Chart: Top25 VIDEO HIP HOP

Chart: Top25_VIDEO_HIP HOP Report Date (TW): 2011-10-04 --- Previous Report Date(LW): 2011-09-25 TW LW TITLE ARTIST RECORD LABEL 1 1 How To Love Lil Wayne Universal Records 2 3 Fly Nicki Minaj Ft. Rihanna Cash Money Records 3 4 Ferrari Boyz Gucci Mane Waka Flocka Flame 1017 Brick Squad / Asylum /Warner Bros Records 4 6 No Sleep (explict) Wiz Khalifa Atlantic Records 5 8 Big Butts Ying Yang Twins Independent 6 21 Marvin & Chardonnay Big Sean Ft. Kanye West And Roscoe Dash Island Def Jam Records 7 9 Lighters Bad Meets Evil Ft. Bruno Mars Interscope Records 8 10 I Know (explict) Yc Universal Republic 9 12 She Be Puttin On Gucci Mane & Waka Flocka Flame 1017 Brick Squad / Asylum /Warner Bros Records 10 14 Stereo Hearts Gym Class Heroes Ft. Adam Levine Decaydance / Fueled By Ramen 11 13 You Dont Know It Travis Porter Porter House / Jive Records 12 15 Oh My (remix) Dj Drama Ft. Trey Songz, 2 Chainz, big Sean eOne Records 13 Dedication To My Ex (miss That) (clean) Lloyd Ft. Andre 3000 Universal Records 14 19 Bumpin Bumpin Kreayshawn Columbia Records 15 7 Work Out J. Cole Roc Nation / Columbia 16 Cant Get Enough (clean Version) J. Cole Ft. Trey Songz Roc Nation Records 17 18 Young N*ggaz Gucci Mane & Waka Flocka Flame 1017 Brick Squad / Asylum /Warner Bros Records 18 Win Young Jeezy Island Def Jam Records 19 17 Ghetto Dreams Common Ft. Nas Interscope Records 20 20 Haters Tony Yayo Ft. 50 Cent, Shawty Lo & Kidd Kidd G-Unit Records 21 2 Otis Kanye West, Jay-z Island Def Jam Records 22 That Way Wale Ft. -

Roxbox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat

RoxBox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Bartender Jucxi D Blackout Careless Whisper Other Side 2 Unlimited 10 Years No Limit Actions & Motives 20 Fingers Beautiful Short Dick Man Drug Of Choice 21 Demands Fix Me Give Me A Minute Fix Me (Acoustic) 2Pac Shoot It Out Changes Through The Iris Dear Mama Wasteland How Do You Want It 10,000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Because The Night 2Pac Feat Dr. Dre Candy Everybody Wants California Love Like The Weather 2Pac Feat. Dr Dre More Than This California Love These Are The Days 2Pac Feat. Elton John Trouble Me Ghetto Gospel 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Eminem Cruella De Vil One Day At A Time 10cc 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dreadlock Holiday Runnin' Good Morning Judge 3 Doors Down I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun The Things We Do For Love Be Like That Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 112 Citizen Soldier Dance With Me Duck & Run Peaches & Cream Every Time You Go Right Here For You Here By Me U Already Know Here Without You 112 Feat. Ludacris It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Hot & Wet Kryptonite 112 Feat. Super Cat Landing In London Na Na Na Let Me Be Myself 12 Gauge Let Me Go Dunkie Butt Live For Today 12 Stones Loser Arms Of A Stranger Road I'm On Far Away When I'm Gone Shadows When You're Young We Are One 3 Of A Kind 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title

Entertainment Plus Karaoke by Title #1 Crush 19 Somethin Garbage Wills, Mark (Can't Live Without Your) Love And 1901 Affection Phoenix Nelson 1969 (I Called Her) Tennessee Stegall, Keith Dugger, Tim 1979 (I Called Her) Tennessee Wvocal Smashing Pumpkins Dugger, Tim 1982 (I Just) Died In Your Arms Travis, Randy Cutting Crew 1985 (Kissed You) Good Night Bowling For Soup Gloriana 1994 0n The Way Down Aldean, Jason Cabrera, Ryan 1999 1 2 3 Prince Berry, Len Wilkinsons, The Estefan, Gloria 19th Nervous Breakdown 1 Thing Rolling Stones Amerie 2 Become 1 1,000 Faces Jewel Montana, Randy Spice Girls, The 1,000 Years, A (Title Screen 2 Becomes 1 Wrong) Spice Girls, The Perri, Christina 2 Faced 10 Days Late Louise Third Eye Blind 20 Little Angels 100 Chance Of Rain Griggs, Andy Morris, Gary 21 Questions 100 Pure Love 50 Cent and Nat Waters, Crystal Duets 50 Cent 100 Years 21st Century (Digital Boy) Five For Fighting Bad Religion 100 Years From Now 21st Century Girls Lewis, Huey & News, The 21st Century Girls 100% Chance Of Rain 22 Morris, Gary Swift, Taylor 100% Cowboy 24 Meadows, Jason Jem 100% Pure Love 24 7 Waters, Crystal Artful Dodger 10Th Ave Freeze Out Edmonds, Kevon Springsteen, Bruce 24 Hours From Tulsa 12:51 Pitney, Gene Strokes, The 24 Hours From You 1-2-3 Next Of Kin Berry, Len 24 K Magic Fm 1-2-3 Redlight Mars, Bruno 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2468 Motorway 1234 Robinson, Tom Estefan, Gloria 24-7 Feist Edmonds, Kevon 15 Minutes 25 Miles Atkins, Rodney Starr, Edwin 16th Avenue 25 Or 6 To 4 Dalton, Lacy J. -

With Machado: Arche-Writings of the Abyss

Posthumous Persona(r)e: Machado de Assis, Black Writing, and the African Diaspora Literary Apparatus by Damien-Adia Marassa Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten, Supervisor ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor ___________________________ Joseph Donahue ___________________________ Nathaniel Mackey ___________________________ Justin Read Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Posthumous Persona(r)e: Machado de Assis, Black Writing, and the African Diaspora Literary Apparatus by Damien-Adia Marassa Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten, Supervisor ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor ___________________________ Joseph Donahue ___________________________ Nathaniel Mackey ___________________________ Justin Read An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Damien-Adia Marassa 2018 Abstract Posthumous Persona(r)e: Machado de Assis, Black Writing, and the African Diaspora Literary Apparatus analyzes the life writings of Machado de Assis (1839-1908) in light of the conditions of his critical reception and translation in English -

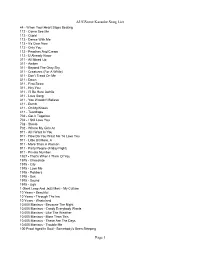

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

TOTALLY TWISTED KARAOKE Songs by Artist 37 SONGS ADDED IN SEP 2021 Title Title (HED) PLANET EARTH 2 CHAINZ, DRAKE & QUAVO (DUET) BARTENDER BIGGER THAN YOU (EXPLICIT) 10 YEARS 2 CHAINZ, KENDRICK LAMAR, A$AP, ROCKY & BEAUTIFUL DRAKE THROUGH THE IRIS FUCKIN PROBLEMS (EXPLICIT) WASTELAND 2 EVISA 10,000 MANIACS OH LA LA LA BECAUSE THE NIGHT 2 LIVE CREW CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS ME SO HORNY LIKE THE WEATHER WE WANT SOME PUSSY MORE THAN THIS 2 PAC THESE ARE THE DAYS CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) TROUBLE ME CHANGES 10CC DEAR MAMA DREADLOCK HOLIDAY HOW DO U WANT IT I'M NOT IN LOVE I GET AROUND RUBBER BULLETS SO MANY TEARS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE UNTIL THE END OF TIME (RADIO VERSION) WALL STREET SHUFFLE 2 PAC & ELTON JOHN 112 GHETTO GOSPEL DANCE WITH ME (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & EMINEM PEACHES AND CREAM ONE DAY AT A TIME PEACHES AND CREAM (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS (DUET) 112 & LUDACRIS DO FOR LOVE HOT & WET 2 PAC, DR DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN (DUET) 12 GAUGE CALIFORNIA LOVE DUNKIE BUTT CALIFORNIA LOVE (REMIX) 12 STONES 2 PISTOLS & RAY J CRASH YOU KNOW ME FAR AWAY 2 UNLIMITED WAY I FEEL NO LIMITS WE ARE ONE 20 FINGERS 1910 FRUITGUM CO SHORT 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 21 SAVAGE, OFFSET, METRO BOOMIN & TRAVIS SIMON SAYS SCOTT (DUET) 1975, THE GHOSTFACE KILLERS (EXPLICIT) SOUND, THE 21ST CENTURY GIRLS TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD 220 KID X BILLEN TED REMIX LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) WELLERMAN (SEA SHANTY) 2 24KGOLDN & IANN DIOR (DUET) WHERE MY GIRLS AT MOOD (EXPLICIT) 2 BROTHERS ON 4TH 2AM CLUB COME TAKE MY HAND -

Johansen^J Handout^J CAMWS 2020 Session 7C.Pdf

“Let’s Call Her Cleopatra, Cleopatra” Jordan Johansen CAMWS | 5/27/2020 | Session 7C [email protected] “Let’s Call her Cleopatra, Cleopatra” – Handout https://camws.org/sites/default/files/meeting2020/abstracts/2344LetCallHerCleopatra.pdf 1. “Cleopatra Had a Jazz Band,” 1917, Sophie Tucker, https://youtu.be/xXCKD0qoXrE Cleopatra had a Jazz Band in her castle on the Nile Ev’ry night she gave a jazz dance in her queer Egyptian style She won Mark Anthony with her syncopated harmony, And as they played she swayed – She knew she had him all the while. ---------- Egypt got the dancing craze, so the wise men say. When they heard that music start, the natives began to dance and say. ---------- Caesar came from Rome to learn to dance the fox-trot and one-step, And when he heard those Jazzers play, He sure was full of pep. 2. “Teenage Cleopatra,” 1962, Tracey Dey, https://youtu.be/RXRTV80fddQ He called me the queen Of all his treasure (Cleopatra) Said I’d rule his world with Only my smile (only my smile) ---------- Now he calls her his teenage Cleopatra (Cleopatra) He calls her his princess Of the Nile (of the Nile) “Let’s Call Her Cleopatra, Cleopatra” Jordan Johansen CAMWS | 5/27/2020 | Session 7C [email protected] 3. “Cleopatra,” 1979, Adam and the Ants, https://youtu.be/ixfQuAZ1UKk C-Cleopatra did a ten-thousand In her lifetime Now that’s a wide mouth C-Cleopatra gave a service With a smile-oh She was a wide mouthed girl A wide mouthed girl C-Cleopatra did a hundred (1-0-0) Roman centurion For after dinner mints C-Cleopatra used a suction Oh so unheard of She was a wide mouthed girl A wide mouthed girl (believe it) 4. -

The Urban Roosters Technologies Marketing Plan

THE URBAN ROOSTERS TECHNOLOGIES MARKETING PLAN Author: Iván Cabanes Ramos Tutor: Marta Estrada Guillén DEGREE IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION 1049 - DEGREE FINAL PROJECT ACADEMIC YEAR 2019-2020 GENERAL INDEX A. INDEX OF FIGURES ............................................................................................. 3 B. INDEX OF TABLES .............................................................................................. 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... 5 2. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS .................................................................................... 7 2.1. Analysis of the sector ......................................................................................... 7 2.2. Internal Analysis ............................................................................................... 12 2.2.1. Company presentation ............................................................................... 12 2.2.2. Mission ...................................................................................................... 15 2.2.3. Vision ......................................................................................................... 15 2.2.4. Values ........................................................................................................ 15 2.2.5. Company resources ................................................................................... 15 2.3. External analysis ............................................................................................. -

Copyright 2020 by Obua JP All Rights Reserved. No Part of This Publication May Be Reproduced in Any Form Or by Any Means, Without the Express Permission of the Author

Copyright 2020 By Obua JP All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, without the express permission of the Author. INTRODUCTION LOVE CHRONICLES 02 Continues the endless journey of love of the poet persona, J.O SPENCER as he continues to traverse the universe in search of true love. He embarks on a journey of self-discovery and his reality appears more an illusion than anything else. The first installment of this poetry collection was a massive success and was downloaded more than 15,000 times in over 18 countries around the world. The poet persona, J.O SPENCER, won numerous awards during the spell of the first collection, “Love Chronicles 01”. This current book however, has all the necessary ingredients to surpass the feats of the last collection published in 2018. J.O SPENCER is ranked no.2 in niume.com poet writers’ list world-wide and has numerous other publications and poetry collections to his name, including the wildly successful collection, “Tears in the rain” which also garnered him several other accolades on the world stage. SPENCER is a Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Nigeria and a full time Criminal and Corporate affairs litigator “Running never stops” The running never stops The streets smell blood, my blood Nothing begets my happiness I time travel to our past as I try to right the wrongs No cherries were popped, no songs were sung All is somber as your mezzo soprano voice awakens My senses and renews my focus The soft ache that represents my pain I just