Kyrgyz Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Snow, Glacier and Water Resources in Asia

IHP/HWRP-BERICHTE Heft 8 Koblenz 2009 Assessment of Snow, Glacier and Water Resources in Asia Assessment of Snow, Glacier and Water Resources in Asia Resources Water Glacier and of Snow, Assessment IHP/HWRP-Berichte • Heft 8/2009 IHP/HWRP-Berichte IHP – International Hydrological Programme of UNESCO ISSN 1614 -1180 HWRP – Hydrology and Water Resources Programme of WMO Assessment of Snow, Glacier and Water Resources in Asia Selected papers from the Workshop in Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2006 Joint Publication of UNESCO-IHP and the German IHP/HWRP National Committee edited by Ludwig N. Braun, Wilfried Hagg, Igor V. Severskiy and Gordon Young Koblenz, 2009 Deutsches IHP/HWRP - Nationalkomitee IHP – International Hydrological Programme of UNESCO HWRP – Hydrology and Water Resource Programme of WMO BfG – Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde, Koblenz German National Committee for the International Hydrological Programme (IHP) of UNESCO and the Hydrology and Water Resources Programme (HWRP) of WMO Koblenz 2009 © IHP/HWRP Secretariat Federal Institute of Hydrology Am Mainzer Tor 1 56068 Koblenz • Germany Telefon: +49 (0) 261/1306-5435 Telefax: +49 (0) 261/1306-5422 http://ihp.bafg.de FOREWORD III Foreword The topic of water availability and the possible effects The publication will serve as a contribution to the of climate change on water resources are of paramount 7th Phase of the International Hydrological Programme importance to the Central Asian countries. In the last (IHP 2008 – 2013) of UNESCO, which has endeavored decades, water supply security has turned out to be to address demands arising from a rapidly changing one of the major challenges for these countries. world. Several focal areas have been identified by the The supply initially ensured by snow and glaciers is IHP to address the impacts of global changes. -

The Formation of Kyrgyz Foreign Policy 1991-2004

THE FORMATION OF KYRGYZ FOREIGN POLICY 1991-2004 A Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of The FletCher SChool of Law and DiplomaCy, Tufts University By THOMAS J. C. WOOD In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2005 Professor Andrew Hess (Chair) Professor John Curtis Perry Professor Sung-Yoon Lee ii Thomas J.C. Wood [email protected] Education 2005: Ph.D. Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University Dissertation Formation of Kyrgyz Foreign Policy 1992-2004 Supervisor, Professor Andrew Hess. 1993: M.A.L.D. Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University 1989: B.A. in History and Politics, University of Exeter, England. Experience 08/2014-present: Associate Professor, Political Science, University of South Carolina Aiken, Aiken, SC. 09/2008-07/2014: Assistant Professor, Political Science, University of South Carolina Aiken, Aiken, SC. 09/2006-05/2008: Visiting Assistant Professor, Political Science, Trinity College, Hartford, CT. 02/2005 – 04/2006: Program Officer, Kyrgyzstan, International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES) Washington DC 11/2000 – 06/2004: Director of Faculty Recruitment and University Relations, Civic Education Project, Washington DC. 01/1998-11/2000: Chair of Department, Program in International Relations, American University – Central Asia, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. 08/1997-11/2000: Civic Education Project Visiting Faculty Fellow, American University- Central Asia, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. Languages Languages: Turkish (advanced), Kyrgyz (intermediate), Russian (basic), French (intermediate). iii ABSTRACT The Evolution of Kyrgyz Foreign PoliCy This empirical study, based on extensive field research, interviews with key actors, and use of Kyrgyz and Russian sources, examines the formation of a distinct foreign policy in a small Central Asian state, Kyrgyzstan, following her independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. -

Central Asia

The Red List of Trees of Central Asia Antonia Eastwood, Georgy Lazkov and Adrian Newton FAUNA & FLORA INTERNATIONAL (FFI) , founded in 1903 and the world’s oldest international conservation organization, acts to conserve threatened species and ecosystems worldwide, choosing solutions that are sustainable, are based on sound science and take account of Published by Fauna & Flora International, Cambridge, UK. human needs. © 2009 Fauna & Flora International ISBN: 9781 903703 27 4 Reproduction of any part of the publication for educational, conservation and other non-profit purposes is authorized without prior permission from the copyright holder, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is a membership organization linking botanic gardens in over 100 is prohibited without prior written permission from the countries in a shared commitment to biodiversity conservation, copyright holder. sustainable use and environmental education. BGCI aims to mobilize The designation of geographical entities in this botanic gardens and work with partners to secure plant diversity for the document and the presentation of the material do not well-being of people and the planet. BGCI provides the Secretariat for imply any expression on the part of the authors or the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. Fauna & Flora International concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. AUTHORS Dr Antonia Eastwood was previously Tree Red List Officer at Fauna & Flora International and is now Plant Ecologist at the Macaulay Institute, Aberdeen, Scotland. THE GLOBAL TREES CAMPAIGN is a joint initiative between FFI and Dr Georgy Lazkov is a plant taxonomist at the Institute BGCI in partnership with a wide range of other organizations around of Biology and Pedology, National Academy of the world. -

The Governance of Central Asian Waters: National Interests Versus Regional Cooperation

The governance of Central Asian waters: national interests versus regional cooperation Jeremy ALLOUCHE The water that serveth all that country is drawn by ditches out of the river Oxus, into the great destruction of the said river, for which cause it falleth not into the Caspian Sea as it hath done in times past, and in short time all that land is like to be destroyed, and to become a wilderness for want of water, when the river of Oxus shall fail. Anthony Jenkinson, 15581 entral Asia2 is defi ned by its relationship to a precious natural resource: water. In fact, water is such an essential element of the region's identity that once Central Asia was known in classical CGreek texts as Transoxiana, which literally means the land on the other side of the Oxus River (now the Amu Darya). It was water that drew international attention to the region shortly after the independence of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan: specifi cally, the fate of the Aral Sea. The Aral Sea has been shrinking since the 1960s, when the Soviet Union decided to divert the region's two major rivers, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, for irrigation purposes. Central Asia was to become a massive centre for cotton production. Today, irrigated agriculture still drives the economies of most of the downstream states in the region: Turkmenistan, and more especially Uzbekistan, rely heavily on cotton production. And the Aral Sea is a massive ecological disaster. Its volume has decreased by 90% and it has divided into two highly saline lakes.3 Four-fi fths of all fi sh species have disappeared and the effects on the health and livelihoods of the local population have been catastrophic. -

Water and Conflict in the Ferghana Valley: Historical Foundations of the Interstate Water Disputes Between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan

Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche Cattedra: Modern Political Atlas Water and Conflict in the Ferghana Valley: Historical Foundations of the Interstate Water Disputes Between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan RELATORE Prof. Riccardo Mario Cucciolla CANDIDATO Alessandro De Stasio Matr. 630942 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2017/2018 1 Sommario Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Water-Security Nexus and the Ferghana Valley ................................................................................. 9 1.1. Water and Conflict ................................................................................................................................. 9 1.1.1. Water uses ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.1.2. Water security and water scarcity ............................................................................................... 10 1.1.3. Water as a potential source of conflict ....................................................................................... 16 1.1.4. River disputes .............................................................................................................................. 25 1.2. The Ferghana Valley ............................................................................................................................ 30 1.2.1. Geography, hydrography, demography and -

Kyrgyz Republic to 2010

Comprehensive Development Framework of the Kyrgyz Republic to 2010 EXPANDING THE COUNTRY'S CAPACITIES National Poverty Reduction Strategy 2003-2005 FOREWORD The current phase of Kyrgyzstan’s development clearly requires quality changes in both the State and the society. Practical steps must be taken in the implementation of the Comprehensive Development Framework of the Kyrgyz Republic to year 2010 (CDF) and the National Poverty Reduction Strategy (NPRS). Timely achievement of high quality results in priority development areas will be the proof of the effectiveness of our actions. Swift adjustments of society and the State to progressive changes will become the key to our common success. Our vision of the future must be kept in mind, together with our history. We must continuously learn and improve ourselves, and work hard to keep up the pace of development. Comprehensive actions, based on modern management methods, are needed. We cannot afford to make mistakes. The loss of time and opportunities is inexcusable in the development of the people, the society, and the history of our nation. We must abandon illusions, overcome inertia and complacency. The community will support the initiatives of the authorities only if plans and actions benefit ordinary people and ensure fuller and more consistent implementation of human rights and freedoms proclaimed in the Constitution of the Kyrgyz Republic. This document, detailing the NPRS, sets out our nation’s approach to dealing with our most immediate and difficult problem – human poverty. Poverty manifests itself in many forms. These include violation of human rights. Poverty, coupled with inequality, increases the vulnerability of social, economic, and political freedoms, generates social tension. -

The Importance of the Geographical Location of the Fergana Valley In

International Journal of Engineering and Information Systems (IJEAIS) ISSN: 2643-640X Vol. 4 Issue 11, November - 2020, Pages: 219-222 The Importance of the Geographical Location of the Fergana Valley in the Study of Rare Plants Foziljonov Shukrullo Fayzullo ugli Student of Andijan state university (ASU) [email protected] Abstract: Most of the rare plants in the Fergana Valley are endemic to this area, meaning they do not grow elsewhere. Therefore, the Fergana Valley is an area with units and environmental conditions that need to be studied. This article gives you a brief overview on rare species in the area. Key words: Fergana, flora, geographical location, mountain ranges. Introduction. The Fergana Valley, the Fergana Valley, is a valley between the mountains of Central Asia, one of the largest mountain ranges in Central Asia. It is bounded on the north by the Tianshan Mountains and on the south by the Gissar Mountains. Mainly in Uzbekistan, partly in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. It is triangular in shape, extending to the northern slopes of the Turkestan and Olay ridges, and is bounded on the northwest by the Qurama and Chatkal ridges, and on the northeast by the Fergana ridge. In the west, a narrow corridor (8–10 km wide) is connected to the Tashkent-Mirzachul basin through the Khojand Gate. Uz. 300 km, width 60–120 km, widest area 170 km, area 22 thousand km. Its height is 330 m in the west and 1000 m in the east. Its general structure is elliptical. It expands from west to east. The surface of the Fergana Valley is filled with Quaternary alluvial and proluvial-alluvial sediments. -

Syr Darya Basin Case Study

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Mariya Pak for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography presented on November 17, 2014. Title: International River Basin Management in the Face of Change: Syr Darya Basin Case Study Abstract approved: _______________________________________________________________ Aaron T. Wolf The conflict over water resources exploitation and sharing in the Aral Sea Basin is one of the most pressing environmental issues yet to be resolved in Central Asia. The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and establishment of the New Independent States (NIS) within the Aral Sea Bain led to conflicting interests vested in water resources with no mediator to solve these water issues. Presently, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya upstream states of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan desire to employ water resources for hydropower; while downstream Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan wish to continue practicing irrigated agriculture. This scarce and over-allocated resource, facing the needs of a growing population and climate change uncertainties, should be managed collaboratively and sustainably to be able to meet and withstand the upcoming challenges. This dissertation examines water management practices in the face of government regime change both in large and small river basins within Central Asia by analyzing international water agreements, correspondence between water managers, official reports, maps, and other archival documents. The analysis shows the inter-republican dynamics in water sector starting from 1950s up to early 2000s. The analysis of water relations within the Syr Darya Basin shows that there are different approaches to the change in political regime in both large and small basins. The results reveal that conflict over water resources in Central Asia existed long before the fall of the Soviet Union both in the large Syr Darya Basin, as well as within its small tributaries. -

Water, Climate, Food, and Environment in the Syr Darya Basin

Water, Climate, Food, and Environment in the Syr Darya Basin Contribution to the project ADAPT Adaptation strategies to changing environments July 2003 Oxana S. Savoskul, Elena V. Chevnina, Felix I. Perziger, Ludmila Yu. Vasilina, Viacheslav L. Baburin, Alexander I. Danshin A.I., Bahtiyar Matyakubov, Ruslan R. Murakaev Edited by O.S. Savoskul Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Natural Resources 2.1 Climate 2.2 Topography 2.3 Land cover 2.4. Land use 2.5.Surface water resources 2.6 Groundwater resources 2.7 Soils 2.8 Water quality and water-related environmental issues 3. Socio-economic issues 3.1 Administrative subdivision 3.2. Population 3.3 Food production 4. Institutional arrangements 5. Projections for the Future 5.1 Climate 5.1.1 Climate Change Scenarios 5.1.2. Climate variability: historic, baseline, modelled 5.2 Population 6. Set up and Description of Models 6.1 Stream Flow Model (SFM) 6.2. Length Growing Period Model (LGPM) 6.3. Water Evaluation and Planning System (WEAP) 7. Impacts 7.1. Hydrology 7.2 Environment 7.3. Food Production 8. Development and assessment of adaptation strategies 8.1. Outline of possible adaptation measures to the CC/CV and SE impacts 8.1.1. Environmental measures 8.1.2. Food security measures 8.1.3. Industrial measures 8.2. Development of adaptation strategies 8.2.1. Environmental AS 8.2.2. Food AS 8.2.3. Industrial AS 8.2.4. Mixed AS 8.3. Assessment of adaptation strategies 8.3.1. Introducing indicators 8.3.2. Setting reference point: Business as Usual, time slice 2070-99 8.3.3. -

Mining Industry and Sustainable Development in Kyrgyzstan

Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development November 2001 No. 110 Mining Industry and Sustainable Development in Kyrgyzstan Valentin Bogdetsky (editor), Vitaliy Stavinskiy, Emil Shukurov and Murat Suyunbaev This report was commissioned by the MMSD project of IIED. It remains the sole Copyright © 2002 IIED and WBCSD. All rights reserved responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Mining, Minerals and MMSD project, Assurance Group or Sponsors Group, or those of IIED or WBCSD. Sustainable Development is a project of the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). The project was made possible by the support of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). IIED is a company limited by guarantee and incorporated in England. Reg. No. 2188452. VAT Reg. No. GB 440 4948 50. Registered Charity No. 800066 Mining Industry and Sustainable Development in Kyrgyzstan Introduction 4 Part I. General information 6 Geography 6 Climate 7 Population 8 Infrastucture 9 The Process of Establishing Kyrgyz Independence 16 The Transition economy 19 Part II. Review of the Extracting Sector 23 History of Development 23 Key Minerals 28 Economic Analysis 38 Operational Conditions and Forecasting 43 The Legal Basis and Licensing Practice in Minerals Exploration 50 Small-Scale and Artisanal Mining Production 53 Consideration of Public Concerns 56 Environmental Impact and Safety Measures 61 The Investment Climate 66 Transparency for Concerned Parties 67 Part III. The Mining Industry: Ecology and Economics 70 Problems of Recultivation and Rehabilitation of Deposits 70 Attraction of Foreign Investment 72 The Integration of the Mining Sector of Kyrgyzstan into the World Economy 76 The Mining Industry and Local Communities 77 The Contribution to Local Communities and Wealth of the Country 80 Information Disclosure and Stakeholder Communication 87 Part IV. -

Water Security in the Syr Darya Basin

Water 2015, 7, 4657-4684; doi:10.3390/w7094657 OPEN ACCESS water ISSN 2073-4441 www.mdpi.com/journal/water Article Water Security in the Syr Darya Basin Kai Wegerich 1,*, Daniel Van Rooijen 2, Ilkhom Soliev 3 and Nozilakhon Mukhamedova 1 1 Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Transition Economies (IAMO), Theodor-Lieser-Str. 2, Halle (Saale) 06120, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 International Water Management Institute—East Africa and Nile Basin Office, IWMI c/o ILRI, PO Box 5689, Addis Ababa 1000, Ethiopia; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Chair of Landscape and Environmental Economics, Technical University of Berlin, Straße des 17, Juni 145, Berlin 10623, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-345-2928138; Fax: +49-345-2928199. Academic Editor: Marko Keskinen Received: 13 May 2015 / Accepted: 19 August 2015 / Published: 27 August 2015 Abstract: The importance of water security has gained prominence on the international water agenda, but the focus seems to be directed towards water demand. An essential element of water security is the functioning of public organizations responsible for water supply through direct and indirect security approaches. Despite this, there has been a tendency to overlook the water security strategies of these organizations as well as constraints on their operation. This paper discusses the critical role of water supply in achieving sustainable water security and presents two case studies from Central Asia on the management of water supply for irrigated agriculture. The analysis concludes that existing water supply bureaucracies need to be revitalized to effectively address key challenges in water security. -

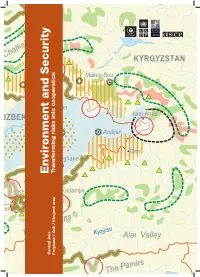

Environment and Security Thematic Issues for Possible ENVSEC Action

���������������������������������� Environment and Security / 1 �� ��� �� �� �� ������� ��� ���������� ��������� �� ��� �� ���������� �� � ���������� �������� �� ��������� �� �� �������� � �� �������� ������� ���������� ���������� �� �������� ��� �� ������� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �� �� � � � ��� � �������� � � �������� � �������� ��������� Transforming risks into cooperation Transforming ������� and Security Environment ������� ������ ���������� �������� ������ � ����� ��� ��� ���� � ��� ������������ ��������� ��������� ��������� Central Asia / Osh Khujand area Ferghana � ����� ����� ���������� ��� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 2 / Environment and Security The United Nations Development Programme is the UN´s Global Development Network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. It operates in 166 countries, working with them on responses to global and national development challenges. As they develop local capacity, the countries draw on the UNDP people and its wide range of partners. The UNDP network links and co-ordinates global and national efforts to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. The United Nations Environment Programme, as the world’s leading intergovernmental environmental organization, is the authoritative source of knowledge on the current state of,