Marian Smith 37 Washington, D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2011 Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance Julia A. Fenton University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Motor Control Commons Recommended Citation Fenton, Julia A., "Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance" (2011). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1436 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Principles of Movement Control that Affect Choreographers’ Instruction of Dance Julia Fenton Preface The purpose of this paper is to inform choreographers of different motor control and skill learning principles that affect instruction of dance and choreography as well as provide a resource for choreographers to make rehearsals more productive. In order to accomplish this task, I adapted the information presented in three main texts, written by Schmidt and Wrisberg, Schmidt and Lee, and Fairbrother, in order for it to be useful to choreographers. I have included dance examples rather than sport examples in order for the choreographer to more easily relate to the information. The in-text citations in this paper were kept to a minimum in order for it to be read more easily. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E62 HON

E62 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks February 1, 2006 Fayard kept their legend alive by giving lec- Norman J. Pera was born in Gary, Indiana, money in the operations of the culinary depart- tures and demonstrations until 2004, when he where he graduated from Horace Mann High ments, throughout the United States Armed suffered a stroke. School in 1939. He served honorably from Forces. Not only is the Nicholas Brother’s dance 1942 to 1946 in the U.S. Navy, including ac- The Clark County School District will greatly skill to be admired and remembered but so is tive duty in the Pacific Theater during Word miss Mr. Doram, who during his years as a their spirit. With each advancement in their ca- War II. teacher was an outstanding educator who reer, they overcame racial discrimination, Upon completing military service, he at- deeply cared about the youth of Nevada. Yet proving that even ignorance cannot dampen tended the Rose Hulman Institute of Tech- his legacy of service to the community will be one’s skills and drive. The Nicholas Brothers nology in Terre Haute, Indiana, and graduated seen for generations to come. stand as a testament and an example to all by in 1948 with a degree in Mechanical Engineer- Mr. Speaker, it is an honor that I am able finding joy in following one’s passion. I join the ing. He worked for Inland Steel of East Chi- to recognize Tyronne E. Doram today, on the NAACP in remembering Fayard Nicholas. cago, Indiana, and retired in 1982 as the As- floor of the House in front of my colleagues. -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

Focus Winter 2002/Web Edition

OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Focus on The School of American Dance and Arts Management A National Reputation Built on Tough Academics, World-Class Training, and Attention to the Business of Entertainment Light the Campus In December 2001, Oklahoma’s United Methodist university began an annual tradition with the first Light the Campus celebration. Editor Robert K. Erwin Designer David Johnson Writers Christine Berney Robert K. Erwin Diane Murphree Sally Ray Focus Magazine Tony Sellars Photography OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Christine Berney Ashley Griffith Joseph Mills Dan Morgan Ann Sherman Vice President for Features Institutional Advancement 10 Cover Story: Focus on the School John C. Barner of American Dance and Arts Management Director of University Relations Robert K. Erwin A reputation for producing professional, employable graduates comes from over twenty years of commitment to academic and Director of Alumni and Parent Relations program excellence. Diane Murphree Director of Athletics Development 27 Gear Up and Sports Information Tony Sellars Oklahoma City University is the only private institution in Oklahoma to partner with public schools in this President of Alumni Board Drew Williamson ’90 national program. President of Law School Alumni Board Allen Harris ’70 Departments Parents’ Council President 2 From the President Ken Harmon Academic and program excellence means Focus Magazine more opportunities for our graduates. 2501 N. Blackwelder Oklahoma City, OK 73106-1493 4 University Update Editor e-mail: [email protected] The buzz on events and people campus-wide. Through the Years Alumni and Parent Relations 24 Sports Update e-mail: [email protected] Your Stars in action. -

A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov

Spring 2010 Ballet Revi ew From the Spring 2010 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland and Misha Chernov On the cover: New York City Ballet’s Tiler Peck in Peter Martins’ The Sleeping Beauty. 4 New York – Alice Helpern 7 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 8 Lisbon – Peter Sparling 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 11 New York – Sandra Genter 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 New York – Sandra Genter 17 Toronto – Gary Smith 19 New York – Marian Horosko 20 San Francisco – Paul Parish David Vaughan 45 23 Paris 1909-2009 Sandra Genter 29 Pina Bausch (1940-2009) Laura Jacobs & Joel Lobenthal 31 A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov Marnie Thomas Wood Edited by 37 Celebrating the Graham Anti-heroine Francis Mason Morris Rossabi Ballet Review 38.1 51 41 Ulaanbaatar Ballet Spring 2010 Darrell Wilkins Associate Editor and Designer: 45 A Mary Wigman Evening Marvin Hoshino Daniel Jacobson Associate Editor: 51 La Danse Don Daniels Associate Editor: Michael Langlois Joel Lobenthal 56 ABT 101 Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan 61 Osipova’s Season Photographers: 37 Tom Brazil Davie Lerner Costas 71 A Conversation with Howard Barr Subscriptions: Don Daniels Roberta Hellman 75 No Apologies: Peck &Mearns at NYCB Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Annie-B Parson 79 First Class Teachers Associates: Peter Anastos 88 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Robert Gres kovic 93 Alfredo Corvino – Elizabeth Zimmer George Jackson 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 23 Paul Parish 100 Check It Out Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, New York City Ballet: Tiler Peck Sarah C. -

CHOREOGRAPHY BASICS By: Max Perry to Choreograph an Effective Routine, a Dancer Will Use Several Techniques to Create a Dance T

CHOREOGRAPHY BASICS By: Max Perry To choreograph an effective routine, a dancer will use several techniques to create a dance that will not only fit the music, but will feel good when danced. The tools we use as choreographers are knowledge of the dance components, a basic idea of phrasing music, and an idea of how the material is to be used (the dancers or organization or company, etc.). ______________________________________ POINTS TO REMEMBER: 1. “A body in motion tends to stay in motion”. There is an initial force required to put the body in motion. Every time there is a change in the directional movement, there is additional force required to make the change. Too many abrupt changes in direction are not as comfortable as letting the body flow in the direction it wants to go, then gradually slow before changing directions. This does not mean you should slow down before every turn - I am referring to energy output only! 2. Choose music that has a wide audience appeal. You do not want a piece of music that sounds dated. The song should sound good every time it is played. If you want artists to take notice, or a national release, the rule is if you hear the song on the radio, it is too late. These songs were recorded months ago. Major established artists do not need a dance. Never go for the obvious - choose a cut from the album that may be released as a single or use a newer artist - possibly an independent artist. 3. Choose material that has a wide audience appeal. -

A Conversation with Mark Morris

Spring2011 Ballet Review From the Spring 2011 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Mark Morris On the cover: Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. 4 Paris – Peter Sparling 6 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 8 Stupgart – Gary Smith 10 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 13 Paris – Peter Sparling 15 Sarasota, FL – Joseph Houseal 17 Paris – Peter Sparling 19 Toronto – Gary Smith 20 Paris – Leigh Witchel 40 Joel Lobenthal 24 A Conversation with Cynthia Gregory Joseph Houseal 40 Lady Aoi in New York Elizabeth Souritz 48 Balanchine in Russia 61 Daniel Gesmer Ballet Review 39.1 56 A Conversation with Spring 2011 Bruce Sansom Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Sandra Genter 61 Next Wave 2010 Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Michael Porter Senior Editor: Don Daniels 68 Swan Lake II Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Darrell Wilkins 48 70 Cherkaoui and Waltz Associate Editor: Larry Kaplan Joseph Houseal Copy Editor: 76 A Conversation with Barbara Palfy Mark Morris Photographers: Tom Brazil Costas 87 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Associates: Peter Anastos 100 Check It Out Robert Greskovic George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall 70 Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Supon David Vaughan Edward Willinger Sarah C. Woodcock CoverphotobyTomBrazil: MarkMorris’FestivalDance. Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. (Photos: Tom Brazil) 76 ballet review A Conversation with – Plato and Satie – was a very white piece. Morris: I’m postracial. Mark Morris BR: I like white. I’m not against white. Morris:Famouslyornotfamously,Satiesaid that he wanted that piece of music to be as Joseph Houseal “white as classical antiquity,”not knowing, of course, that the Parthenon was painted or- BR: My first question is . -

An Early American Sleeping Beauty from Ballet Review Summer 2015

Summer 2015 Ball et Review An Early American Sleeping Beauty from Ballet Review Summer 2015 CoverphotographbyCostas:WendyWhelanandNikolajHübbe inBalanchine’sLaSonnambula . © 2015 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Brooklyn – Susanna Sloat 5 Berlin – Darrell Wilkins 7 London – Leigh Witchel 9 New York – Susanna Sloat 10 Toronto – Gary Smith 12 New York – Karen Greenspan 14 London – David Mead 15 New York – Susanna Sloat 16 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 19 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 21 New York – Harris Green 39 22 San Francisco – Rachel Howard 23 London – Leigh Witchel Ballet Review 43.2 24 Brooklyn – Darrell Wilkins Summer 2015 26 El Paso – Karen Greenspan Editor and Designer: 31 San Francisco – Rachel Howard Marvin Hoshino 32 Chicago – Joseph Houseal Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Sharon Skeel 34 Early American Annals of Senior Editor: Don Daniels The Sleeping Beauty Associate Editor: 54 Christopher Caines Joel Lobenthal 39 Tharp and Tudor for a Associate Editor: New Generation Larry Kaplan Michael Langlois Webmaster: 46 A Conversation with Ohad Naharin David S. Weiss Copy Editors: Leigh Witchel Barbara Palf y* 54 Ashton Celebrated Naomi Mindlin Joel Lobenthal Photographers: Tom Brazil 62 62 A Conversation with Nora White Costas Nina Alovert Associates: 70 The Mikhailovsky Ballet Peter Anastos Robert Greskovic David Mead George Jackson 76 A Conversation with Peter Wright Elizabeth Kendall Paul Parish James Sutton Nancy Reynolds 89 Indianapolis Evening of Stars James SuZon David Vaughan Leigh Witchel Edward Willinger 70 94 La Sylphide Sarah C. Woodcock Jay Rogoff 98 A Conversation with Wendy Whelan 106 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 110 Music on Disc – George Dorris Cover photograph by Costas: Wendy Whelan 116 Check It Out and Nikolaj Hübbe in La Sonnambula . -

The THREE's a CROWD

The THREE’S A CROWD exhibition covers areas ranging from Hong Kong to Slavic vixa parties. It looks at modern-day streets and dance floors, examining how – through their physical presence in the public space – bodies create temporary communities, how they transform the old reality and create new conditions. And how many people does it take to make a crowd. The autonomous, affect-driven and confusing social body is a dynamic 19th-century construct that stands in opposition to the concepts of capitalist productivity, rationalism, and social order. It is more of a manifestation of social dis- order: the crowd as a horde, the crowd as a swarm. But it happens that three is already a crowd. The club culture remembers cases of criminalizing the rhythmic movement of at least three people dancing to the music based on repetitive beats. We also remember this pandemic year’s spring and autumn events, when the hearts of the Polish police beat faster at the sight of crowds of three and five people. Bodies always function in relation to other bodies. To have no body is to be nobody. Bodies shape social life in the public space through movement and stillness, gath- ering and distraction. Also by absence. Regardless of whether it is a grassroots form of bodily (dis)organization, self-cho- reographed protests, improvised social dances, artistic, activist or artivist actions, bodies become a field of social and political struggle. Together and apart. ARTISTS: International Festival of Urban ARCHIVES OF PUBLIC Art OUT OF STH VI: SPACE PROTESTS ABSORBENCY -

Choreography for the Camera: an Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1992 Choreography for the Camera: An Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study Vana Patrice Carter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, and the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Vana Patrice, "Choreography for the Camera: An Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study" (1992). Master's Theses. 894. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/894 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA: AN HISTORICAL, CRITICAL, AND EMPIRICAL STUDY by Vana Patrice Carter A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 1992 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA: AN HISTORICAL, CRITICAL, AND EMPIRICAL STUDY Vana Patrice Carter, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1992 This study investigates whether a dance choreographer’s lack of knowledge of film, television, or video theory and technology, particularly the capabilities of the camera and montage, restricts choreographic communication via these media. First, several film and television choreographers were surveyed. Second, the literature was analyzed to determine the evolution of dance on film and television (from the choreographers’ perspective). -

Ballet Terms Definition

Fundamentals of Ballet, Dance 10AB, Professor Sheree King BALLET TERMS DEFINITION A la seconde One of eight directions of the body, in which the foot is placed in second position and the arms are outstretched to second position. (ah la suh-GAWND) A Terre Literally the Earth. The leg is in contact with the floor. Arabesque One of the basic poses in ballet. It is a position of the body, in profile, supported on one leg, with the other leg extended behind and at right angles to it, and the arms held in various harmonious positions creating the longest possible line along the body. Attitude A pose on one leg with the other lifted in back, the knee bent at an angle of ninety degrees and well turned out so that the knee is higher than the foot. The arm on the side of the raised leg is held over the held in a curved position while the other arm is extended to the side (ah-tee-TEWD) Adagio A French word meaning at ease or leisure. In dancing, its main meaning is series of exercises following the center practice, consisting of a succession of slow and graceful movements. (ah-DAHZ-EO) Allegro Fast or quick. Center floor allegro variations incorporate small and large jumps. Allonge´ Extended, outstretched. As for example, in arabesque allongé. Assemble´ Assembled or joined together. A step in which the working foot slides well along the ground before being swept into the air. As the foot goes into the air the dancer pushes off the floor with the supporting leg, extending the toes. -

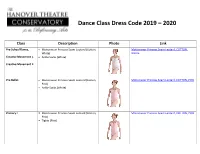

Dance Class Dress Code 2019 – 2020

Dance Class Dress Code 2019 – 2020 Class Description Photo Link Pre-School Dance, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, White) WHITE Creative Movement I, Ankle Socks (White) Creative Movement II Pre-Ballet Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, PINK Pink) Ankle Socks (White) Primary I . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, PINK Pink) . Tights (Pink) Primary II . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, Light Blue) LIGHT BLUE . Tights (Pink) Primary III . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Royal Blue) ROYAL BLUE . Tights (Pink) Teen Ballet & . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Hunter Green) HUNTER GREEN Adult Ballet II . Tights (Pink) Level A . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Fuchsia) FUCHSIA . Tights (Pink) Level B . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Bright Red) BRIGHT RED . Tights (Pink) Level C . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Maroon) MAROON . Tights (Pink) Level D, . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Black) BLACK Boys & Girls Club, . Tights (Pink) Adult Ballet Youth Ballet Company . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, (Apprentice) Butter) BUTTER . Tights (Pink) Youth Ballet Company . Any style white leotard (Junior) . Tights (Pink) Youth Ballet Company . Any style black leotard (Senior) . On the 2nd Saturday of each month any color leotard is allowed. Tights (Pink) Boys Ballet . Motionwear Cap Sleeve Fitted T-Shirt . Motionwear Mens Cap Sleeve Fitted t-shirt, (Silkskyn, White) SILKSKYN, WHITE .