Italy 2012.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. the Communications Sector in Italy

2. The communications sector in Italy 2. The communications sector in Italy 2.1. Telecommunications In a picture of progressive deterioration of the macroeconomic situation, the trend of contraction of the telecommunications market, on both fixed and mobile network, already observed for some years, was confirmed in 2011. In this context, the elements which best qualify the Italian telecommunications market, show no substantial change in 2011 compared to the last two years. These elements can be summed up as follows: i) the expenditure of families and companies in telecommunications services continues to fall, with a slight acceleration compared to 2010; ii) the reduction in the prices of telecommunications services to both private and business customers, on both fixed and mobile networks, is constant; iii) the contraction in voice calls on dial-up network continues, with a reduction of 11.7% in the number of minutes consumed, while voice traffic from the mobile network has increased by another 10% in the last year; iv) the spread of broadband services on fixed and mobile network has produced further growth in income deriving from data services; v) there is still growth, but with indications of the saturation of the relative market, in the virtual mobile telephony compartment; vi) with regard to the competitive situation, the erosion of Telecom Italia's total market share continues; vii) in last autumn, an auction was held for the assigning of the usage rights of the frequencies in the 800, 1,800, 2,000 and 2,600 MHz bands, which led to a total commitment of the mobile operators for € 3.9 billion; viii) on the other hand, the reduction in investments in infrastructures is confirmed;9 ix) The gross profit of the sector is substantially stable, also thanks to the continuous restructuring and cost containment actions carried out by the telecommunications companies. -

Pubblicazioni Pasquali MAGGIO 2013 Copia

Francesca Pasquali ELENCO DELLE PUBBLICAZIONI “The democratic (media) revolution: A parallel genealogy of political and media participation”, in N. Carpentier, K. Schroder, and L. Hallett (eds.), Transformations, Routledge forthcoming (con N. Carpentier and P. Dahlgren). “Virtual Shadowing, Online Ethnographies and Social Networking Studies”, in G. Patriarche, H. Bilandzic, J. Linaa Jensen, J. Jurisic (eds.), Researching Transforming Audiences: Methodological Issues and Innovations in Audience Research, Routledge, forthcoming (with N. Vittadini). “A new sense of place: social e location-based media fra socievolezza e partecipazione”, in F. Adobati-M. Peretti, ICONEMI, Bergamo, Sestante (in corso di stampa). “Waves of media democratization: A brief history of contemporary participatory practices in the media sphere”, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Published online before print May 16, 2013, doi: 10.1177/1354856513486529 (with Nico Carpentier and Peter Dalhgren) “Networked audiences and small scale groups’ belongings: viewing, sharing and archiving TV content in the Italian social media scenario”, Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, Special Issue “Networked belonging and networks of Belonging” - COST ACTION ISO906, 2012, pp. 181–196. “L’auteur est mort. Vive l’auteur!”, in J. Schiavini Trezzi, Mosaico francese, Moretti e Vitali, 2012, pp. 389-402. “Pornografia, sexting e contenuti ‘inappropriati’ online”, in G. Mascheroni (a cura di), I ragazzi e la rete. La ricerca EU Kids e il caso Italia, La Scuola, 2012, pp. 185-213. “Ritorno al futuro, generazioni letterarie e racconti di generazione. Media e immaginario letterario dagli anni Ottanta a oggi (e viceversa)”, in G. Boccia Artieri, F. Colombo, G. Del Grosso Destrieri, F. Pasquali, M. Sorice (eds.), Media e Generazioni nella società italiana, Angeli , 2012, pp. -

Network Spirits

“COMPUTER NETWORKS HISTORIES” LUGANO, 14–15 DECEMBER 2017 ILLUSTRATED CONFERENCE REVIEW NETWORK SPIRITS Conference organized at the Università del- la Svizzera italiana by Professor of Media Studies Gabriele Balbi and his collaborators Gianliugi Negro and Paolo Bory, as part of a series of unfolding activities within the Institute of Media and Journalism centered on the history of science, technology, and computing. The China Media Observatory host- ed by the University, under the direction and care of Balbi and Negro, provided the rationale for a substantive focus during the conference on Chinese computer networks. Sponsored by the Swiss Association for History and Computing, presided by Chris- tiane Sibille; by infoclio.ch, the por- tal of professional historical research in Switzerland, directed by Enrico Natale; and the Swiss Academy of Humanities and Social Sciences. Review by Vlad Atanasiu, Department of In- formatics, University of Fribourg, Switzer- land. EMBEDDING TOPOLOGIES The picture on the left shows Europe’s fast- est supercomputer in 2017, “Piz Daint” of the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS), situated in the city of Lugano, on the southern slopes of the Alps. The rumbling emanating from the machine is not much different from that of an ancestral mill, only that it is not wheat or corn, but digital data that is crunched at the rate of 25 Petaflops. The data arrives and de- parts through 100 Gbit/s optic fiber cables set over the mountain passes of St Gothard, Simplon, and St Bernardino, serving academic institutions spread throughout the country, the CERN – cradle of the World Wide Web – at the French border, and various customers in the wider world. -

60.9 Million PRESS FREEDOM 2013 STATUS: Partly Free

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2013 1 ITALY 2012 2013 POPULATION: 60.9 million INTERNET FREEDOM STATUS FREE FREE INTERNET PENETRATION 2012: 58 percent SOCIAL MEDIA/ICT APPS BLOCKED: No Obstacles to Access (0-25) 4 5 POLITICAL/SOCIAL CONTENT BLOCKED: No Limits on Content (0-35) 7 6 BLOGGERS/ICT USERS ARRESTED: No Violations of User Rights (0-40) 12 12 PRESS FREEDOM 2013 STATUS: Partly Free Total (0-100) 23 23 * 0=most free, 100=least free KEY DEVELOPMENTS: MAY 2012 – APRIL 2013 Despite limited progress, Italy continued to lag behind most other countries of the European Union in terms of internet penetration and average speed (see OBSTACLES TO ACCESS). Dozens of file-sharing and video-streaming websites were blocked over the past year for illegally hosting copyrighted materials (see LIMITS ON CONTENT). The Court of Cassation clarified that a 1948 law prohibiting “clandestine press” could not be applied to blogs, easing fears that blogs could face blocking for failing to register with the authorities (see LIMITS ON CONTENT). Social media and blogging were critical in the nascent Five Star Movement’s success in the February 2013 parliamentary elections, in which it received more votes than any single party (see LIMITS ON CONTENT). A Livorno court decided that an insulting Facebook post can be considered as defamation by “other means of publicity,” since the social network allows for the broad diffusion of posts. In the case, a user was found guilty of defaming her former employer and ordered to pay a fine. The ruling may open the door for further defamation cases related to Facebook posts (see VIOLATIONS OF USER RIGHTS). -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: ITALY Mapping Digital Media: Italy

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: ITALY Mapping Digital Media: Italy A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Gianpietro Mazzoleni, Giulio Vigevani (lead reporters) Sergio Splendore (reporter) EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Francesca Fanucci EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; Miguel Castro, special projects manager; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 10 August 2011 Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 11 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Annuario 2012 I Dati Del Registro .It

Annuario 2012 I dati del Registro .it 25 anni Annuario Registro Dati 2012 Annuario 2012 è un supplemento di focus.it Direttore responsabile 3 una rivoluzione quotidiana a daily revolution Marco Ferrazzoli di Marco Ferrazzoli Coordinamento editoriale Anna Vaccarelli 6 il Registro, questo conosciuto Impaginazione the Registry, this familiar institution Giuliano Kraft di Anna Vaccarelli Progetto grafico e infografica 3Nero s.a.s. uno studio del Cnr mostra il digital divide 8 Comitato redazionale Cnr study reveals the digital divide Francesca Nicolini di Maurizio Martinelli e Michela Serrecchia Stefania Fabbri Beatrice Lami 11 più visibilità e più business per le imprese con il .it Fonte dati more visibility and more business Unità sistemi e sviluppo for companies with a dot .it domain tecnologico del Registro .it. di Stefania Fabbri Elaborazione a cura di Lorenzo Luconi Trombacchi 13 il Registro .it: l’anagrafe dei domini Stampa the Italian Registry: the database of domains Pacini Editore S.p.A. Via A. Gherardesca 56121 Ospedaletto (PI) 14 un po’ di storia a bit of history Direzione - Redazione Unità relazioni esterne, media e comunicazione 16 tutti i numeri di .it del Registro .it all the numbers for .it Via G. Moruzzi, 1 I-56124 Pisa tel. +39 050 313 98 11 2 3 Idn (Internationalized Domain Names) fax +39 050 315 27 13 IDN (Internationalized Domain Names) e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.registro.it/ 2 4 imprese, cittadini ed enti pubblici Responsabile del Registro .it businesses, citizens and public bodies Domenico Laforenza -

The Multifaceted Effect of Broadband Internet on Political Participation

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES POLITICS 2.0: THE MULTIFACETED EFFECT OF BROADBAND INTERNET ON POLITICAL PARTICIPATION Filipe R. Campante Ruben Durante Francesco Sobbrio Working Paper 19029 http://www.nber.org/papers/w19029 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2013 We are very grateful to “Osservatorio Banda Larga-Between” for providing us access to the data on ADSL coverage of Italian municipalities used in this paper. We also thank Nicola D’Amelio and Giuseppe Piraino for their help with data collection, and Stefano Gagliarducci for sharing his dataset on Italian municipal elections. We thank Adriana Camacho, Stefano DellaVigna, Matthew Ellman, Leopoldo Fergusson, Ed Glaeser, Rema Hanna, Andrea Ichino, Andrea Mattozzi, Luke Miner, Luigi Pascali, Nicola Persico, Giacomo Ponzetto, Andrei Shleifer, David Yanagizawa-Drott, and seminar participants at the European University Institute, Harvard University, the Institut d’Anàlisi Econòmica, Tufts University, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, and at the X Workshop in Media Economics (Bogotá). Maria Chiara Cavalleri and Marta Fana provided excellent research assistance. Finally, special thanks go to Silvio Berlusconi for forcing early elections in 2013 and thus expediting our data collection process. The usual disclaimers apply. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2013 by Filipe R. Campante, Ruben Durante, and Francesco Sobbrio. All rights reserved. -

Italy Promotes Freedom of Speech Online by Allowing Access to Most Con- Tent

Italy Italy promotes freedom of speech online by allowing access to most con- tent. However, the Italian government has been slow to address many online privacy and freedom-of-information concerns, and Italy lags behind much of Europe in terms of Internet pene- tration. Italy, like much of the Euro- pean Union (EU), regulates certain categories of Web sites, including child pornography and gambling. Additionally, a recently proposed law, dubbed the Levi-Prodi law, would impose registration and taxes on anyone creating ‘‘edi- torial content,’’ including bloggers. The law, which has faced significant opposi- tion, has thus far not passed. Background Italy has had a multiparty, democratic government since 1946. The 1948 constitution was written to prevent a return to early 20th-century fascism, and powers were spread among the different branches of government to limit the powers of the head of state. During the cold war, the country feared a communist overthrow, and as a result power RESULTS AT A GLANCE No Evidence Suspected Selective Substantial Pervasive Filtering of Filtering Filtering Filtering Filtering Filtering Political Social Conflict and security Internet tools Not Other Factors Low Medium High Applicable Transparency Consistency 318 Italy KEY INDICATORS GDP per capita, PPP (constant 2005 international dollars) 28,682 Life expectancy at birth (years) 81 Literacy rate (percent of people age 15þ)99 Human development index (out of 179) 19 Rule of law (out of 211) 81 Voice and accountability (out of 209) 28 Democracy index (out of 167) 29 (Full democracy) Digital opportunity index (out of 181) 28 Internet users (percent of population) 49 Source by indicator: World Bank 2009a, World Bank 2009a, World Bank 2009a, UNDP 2008, World Bank 2009b, World Bank 2009b, Economist Intelligence Unit 2008, ITU 2007, ITU 2008. -

Anatomy of the Italian Web TV Ecosystem

D i g i t a l Communication P o l i c i e s | 87 Anatomy of the Italian Web TV ecosystem. Current issues and future challenges. 12 13 Emiliano Treré ; Valentina Bazzarin ; The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the emergent Italian Web TV ecosystem. We begin by sketching a summary of the Italian media scenario, focusing on three related aspects: the Rai-Mediaset duopoly, the Berlusconi anomaly and digital evolution of the TV system. We then switch to the Italian digital resistance scenario and describe some of the most interesting experiences developed in the Italian context. In the third part, we dissect and analyze the phenomenon of Italian Web TVs, exploring its roots, legal status, producers and audiences. We conclude by providing a reflection on Italian Web TVs as an ecosystem, both by pointing out some future challenges it will face within the Italian media scenario and by focusing on the role of active citizens and unprofessional producers in changing the scenario and in advocating pluralism and creativeness. 1. The Italian media scenario14 Before we introduce and investigate the Web TV ecosystem, we first begin this article by providing an overview of the Italian television scenario. As highlighted by Ferrari & Ardizzoni (2010) and by Padovani (2007, 2010) the Italian landscape is defined by the following characteristics: close control of the State over Italian media, 12 [email protected]; Associate Professor, Faculty of Political and Social Sciences, Autonomous University of Querétaro, México. 13 Researcher, Department of Communication Studies, University of Bologna, Italy; Visiting researcher, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, U.S. -

The Multifaceted Effect of Broadband Internet on Political Participation Faculty Research Working Paper Series

Politics 2.0: The Multifaceted Effect of Broadband Internet on Political Participation Faculty Research Working Paper Series Filipe Campante Harvard Kennedy School Ruben Durante Sciences Po Francesco Sobbrio European University Institute May 2013 RWP13-014 Visit the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper series at: http://web.hks.harvard.edu/publications The views expressed in the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. Faculty Research Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. www.hks.harvard.edu Politics 2.0: The Multifaceted Effect of Broadband Internet on Political Participation∗ Filipe Campantey Ruben Durantez Francesco Sobbrio§ May 2013 ABSTRACT We investigate the impact of the diffusion of high-speed Internet on different forms of political participation, using data from Italy. We exploit differences in the availability of ADSL broadband technology across municipalities, using the exogenous variation induced by the fact that the cost of providing ADSL-based Internet services in a given municipality depends on its relative position in the pre-existing voice telecommunica- tions infrastructure. We first show that broadband Internet had a substantial negative effect on turnout in parliamentary elections between 1996 and 2008. However, we also find that it was positively associated with other forms of political participation, both online and offline: the emergence of local online grassroots protest movements, and turnout in national referenda (largely opposed by mainstream parties). -

Annuario 2012 I Dati Del Registro .It

Annuario 2012 I dati del Registro .it 25 anni Annuario Registro Dati 2012 Annuario 2012 è un supplemento di focus.it Direttore responsabile 3 una rivoluzione quotidiana a daily revolution Marco Ferrazzoli di Marco Ferrazzoli Coordinamento editoriale Anna Vaccarelli 6 il Registro, questo conosciuto Grafica e impaginazione the Registry, this familiar institution Giuliano Kraft di Anna Vaccarelli Comitato redazionale Francesca Nicolini 8 uno studio del Cnr mostra il digital divide Stefania Fabbri Cnr study reveals the digital divide Beatrice Lami di Maurizio Martinelli e Michela Serrecchia Fonte dati Unità sistemi e sviluppo tecnologico del Registro .it. 11 più visibilità e più business per le imprese con il .it more visibility and more business Elaborazione a cura di Lorenzo Luconi Trombacchi for companies with a dot .it domain di Stefania Fabbri Stampa Pacini Editore S.p.A. Via A. Gherardesca 13 il Registro .it: l’anagrafe dei domini 56121 Ospedaletto (PI) the Italian Registry: the database of domains Direzione - Redazione Unità relazioni esterne, media e 14 un po’ di storia comunicazione a bit of history del Registro .it Via G. Moruzzi, 1 I-56124 Pisa 16 tutti i numeri di .it tel. +39 050 313 98 11 all the numbers for .it fax +39 050 315 27 13 e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.registro.it/ 2 3 Idn (Internationalized Domain Names) IDN (Internationalized Domain Names) Responsabile del Registro .it Domenico Laforenza 2 4 imprese, cittadini ed enti pubblici Registrazione al Tribunale di Pisa businesses, citizens and public bodies -

NEWSLETTER N. 17.Indd

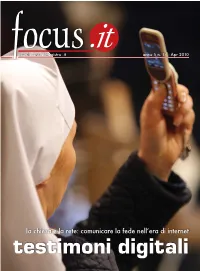

newsletter del Registro .it anno 5 n. 17 - Apr 2010 la chiesa e la rete: comunicare la fede nellʼera di internet testimoni digitali 3 internet, la nuova radio the internet, the new radio di Domenico Laforenza newsletter del Registro .it 6 dalla Chiesa un antidoto Anno 5, numero 17 - Aprile 2010 al caos digitale: Direttore responsabile “diamo un’anima alla rete” Director in charge the Church’s antidote Luca Trombella to digital chaos: Coordinamento editoriale “let’s give a soul to the net” Editorial coordinator di Marco Ferrazzoli Anna Vaccarelli .it, 562mila pagine web Impaginazione ed elaborazione immagini 12 Paging and image processing parlano di religione Giuliano Kraft 562,000 .it web pages talk about religion Fotografi e Photos di Luca Trombella Romano Siciliani e Cristian Gennari / Imago Mundi, Archivio Fondazione Missio - Carlos Rodriguez Soto, 18 quando il sagrato è virtuale: Giuliano Kraft online 70 parrocchie su 100 In redazione 2 preti su 3 scrivono email Editors when the parvis is virtual: Giorgia Bassi, Stefania Fabbri, Paolo Gentili, 70% parishes are connected Beatrice Lami, Francesca Nicolini 2 priests out of 3 write emails Traduzioni di Rita Marchetti Translations English for Academics snc di Adrian John Wallwork 28 sacerdoti e Ict, binomio vincente su internet più opportunità che rischi Stampa priests and ICT, a winning combination Printed by Pacini Editore S.p.A. sommario/summary more opportunities than risks on the web Via A. Gherardesca di Lorenzo Cantoni 56121 Ospedaletto (PI) Direzione - Redazione 32 Africa, dove la rete è un lusso Editorial Offi ces “internet sarà la voce Unità relazioni esterne, media e comunicazione di chi non può parlare” del Registro .it Via G.