Patterns of Bryophyte and Lichen Diversity in Interior and Coastal Cedar-Hemlock Forests of British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Park User Fees Bcparks.Ca/Fees

Park User Fees bcparks.ca/fees PARK – DESCRIPTION FEE ADAMS LAKE - frontcountry camping $13.00 /party/night AKAMINA-KISHINENA - backcountry camping $5.00 /person/night ALICE LAKE - frontcountry camping $35.00 /party/night ALICE LAKE - group camping base fee $120.00 /group site/night ALICE LAKE - sani station $5.00 /discharge ALICE LAKE - walk/cycle in - frontcountry camping $23.00 /party/night ALLISON LAKE - frontcountry camping $18.00 /party/night ANHLUUT’UKWSIM LAXMIHL ANGWINGA’ASANSKWHL NISGA - frontcountry camping $20.00 /party/night ANSTEY-HUNAKWA - camping-annual fee $600.00 /vessel ANSTEY-HUNAKWA - marine camping $20.00 /vessel/night ARROW LAKES - Shelter Bay - frontcountry camping $20.00 /party/night BABINE LAKE MARINE - Pendleton Bay, Smithers Landing - frontcountry camping $13.00 /party/night BABINE MOUNTAINS – cabin $10.00 /adult/night BABINE MOUNTAINS – cabin $5.00 /child/night BAMBERTON - frontcountry camping $20.00 /party/night BAMBERTON - winter frontcountry camping $11.00 /party/night BEAR CREEK - frontcountry camping $35.00 /party/night BEAR CREEK - sani station $5.00 /discharge BEATTON - frontcountry camping $20.00 /party/night BEATTON - group picnicking $35.00 /group site/day BEAUMONT - frontcountry camping $22.00 /party/night BEAUMONT - sani station $5.00 /discharge BIG BAR LAKE - frontcountry camping $18.00 /party/night BIG BAR LAKE - Upper - long-stay camping $88.00 /party/week BIRKENHEAD LAKE - frontcountry camping $22.00 /party/night BIRKENHEAD LAKE - sani station $5.00 /discharge BLANKET CREEK - frontcountry camping -

Wells Gray Park Master Plan

2-2-4-1-27 WELLS GRAY PARK MASTER PLAN February, 1986 Ministry of Lands Parks & Housing Parks & Outdoor Recreation Div. i TABLE OF CONTENTS PLAN HIGHLIGHTS PLAN ORGANIZATION SECTION 1 - PARK ROLE 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.2 THE ROLE OF WELLS GRAY PARK 5 1.2.1 Regional and Provincial Context 5 1.2.2 Conservation Role 5 1.2.3 Recreation Role 7 1.3 ZONING 8 SECTION 2 - PARK MANAGEMENT 12 2.1 NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVES AND POLICIES 12 2.1.1 Land and Tenures (a) Park Boundaries 12 (b) Inholdings and Other Tenures 14 (c) Trespasses 14 2.1.2 Water (a) General Principle 16 (b) Impoundment, Diversion, etc. 16 2.1.3 Vegetation (a) General Principle 16 (b) Current Specific Policies 16 2.1.4 Wildlife (a) General Principle 18 (b) Current Specific Policies 19 2.1.5 Fish (a) General Principle 21 (b) Current Specific Policies 21 2.1.6 Cultural Heritage (a) General Principle 22 (b) Current Specific Policies 22 2.1.7 Visual Resources (a) General Principle 23 (b) Current Specific Policies 23 2.1.8 Minerals Resources (a) General Principle 24 ii 2.2 VISITOR SERVICES OBJECTIVES AND POLICIES 24 2.2.1 Introduction (a) General Concept 24 (b) Access Strategy 26 (c) Information & Interpretation Strategy 26 2.2.2 Visitor Opportunities 26 (a) Auto-access Sightseeing and Touring 26 (b) Auto-access Destination 28 (c) Visitor Information Programs 28 (d) Winter Recreation 31 (e) Wild River Recreation 31 (f) Motorboat Touring 32 (g) Angling 32 (h) Hunting 32 (i) Hiking 33 (j) Canoeing 33 (k) Horseback Riding 34 (1) Alpine Appreciation 34 (m) Research 34 2.2.3 -

DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY HELMCKEN FALLS Photo: Max Zeddler

INTERLAKES DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY HELMCKEN FALLS Photo: Max Zeddler DESTINATION BC REPRESENTATIVES Seppe Mommaerts MANAGER, DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT Jody Young SENIOR PROJECT ADVISOR, DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT [email protected] CARIBOO CHILCOTIN COAST TOURISM ASSOCIATION Jolene Lammers DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT COORDINATOR 250 392 2226 ext. 209 [email protected] Amy Thacker CEO 250 392 2226 ext. 200 [email protected] THOMPSON OKANAGAN TOURISM ASSOCIATION Ellen Walker-Matthews VICE PRESIDENT, DESTINATION & INDUSTRY DEVELOPMENT 250 860 5999 ext.215 [email protected] MINISTRY OF TOURISM ARTS AND CULTURE Amber Mattock DIRECTOR, LEGISLATION AND DESTINATION BC GOVERNANCE 250 356 1489 [email protected] INDIGENOUS TOURISM ASSOCIATION OF BC 604 921 1070 [email protected] INTERLAKES | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................1 7. STRATEGY AT A GLANCE ............................................................... 39 II. ACRONYMS ..........................................................................................5 8. STRATEGIC PRIORITIES ..................................................................40 Theme 1: Strategically invest in targeted infrastructure upgrades that 1. FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..............................7 will support tourism growth Theme 2: Lead strategic growth through continued collaboration 2. INTRODUCING THE STRATEGY .....................................................9 Theme -

Wells Gray Park

reconnaissance and preliminary recreation plan wells gray park by c.p. lyons Parks Section forest economics division b.c. Forest Service – 1941 – Reference No. p41 General file: 0135867 preface Wells Gray Park is an outstanding potential recreational area; it has remarkable scenic attractions as well as exceptional fishing, big game hunting and wilderness area possibilities. The Park is located about 100 miles north of Kamloops in the Kamloops Forest District and is accessible by the Caribou and North Thompson River regions. The proper development of this area as a Provincial Park depends upon planned recreational management in order to adequately provide for present and future use. With this objective in mind, a reconnaissance of the Park was made in 1940 by Mr. C.P. Lyons, whose report and preliminary recreation plan is herein detailed. Sufficient information is now available to introduce planned management but it is still necessary to make further investigations before extensive developments take place. For the time being commercial lodge and campsite privileges on Crown land should be restricted to a minimum and, if possible, confined to guides of hunting and fishing parties who now make use of the Park. It would be particularly advisable to limit locations for commercial enterprises to the specific regions detailed in this report and to stipulate a maximum value for construction and development work. By so doing adjustments could be more easily made to suit any detailed management plan which may be prepared in the future. Existing private use on Crown land should be brought under a permit system and there is no reason why expansion in this direction should not be encouraged. -

NTV-Visitor-Guide.Pdf

1 SIMPCW “People of the North Thompson River” The Simpcw are a Culturally Proud Community Valuing Healthy, Holistic Lifestyles based upon Respect, Responsibility and Continuous Participation in Growth and Education Since time immemorial the Simpcw occupied the lands of the North Thompson River upstream from McLure to the headwaters of the Fraser River from McBride to Tete Jeune Cache, east to Jasper and south to the headwaters of the Athabasca River. The Simpcw are a division of the Secwepemc, or Shuswap. The Simpcw speak the Secwepemc dialect, a SalishanSalis language, shared among many of the First Nations in the FraserFr and Thompson River drainage. The Simpcw traveled throughoutthrou the spring, summer and fall, gathering food and materialsmate which sustained them through the winter. During the winterwin months they assembled at village sites, in the valleys close to rivers, occupying semi-underground houses. Archaeological studiesst have identifi ed winter home sites and underground foodfo cache sites at a variety of locations including Finn Creek, Vavenby,V Birch Island, Chu Chua, Barriere River, Louis Creek, Tete Jeune, Raush River, Jasper National Park and Robson Park. Simpcw peoplepe value their positive relationships with non-native people in thethe NorthNorth ThompsonThomp and Robson Valleys. They also recognize that their key strength lies in maintaining links to their traditional heritage and look forward to securing a place for their children in contemporary society that they can embrace with pride. The Simpcw culture is community driven for the management, conservation and protection of all the Creator’s resources. Box 220, Barriere, B.C. V0E 1E0 Ph#250-672-9995 Fax#250-672-5858 Band offi ce location: 15km north of Barriere on Dunn Lake Road Offi ce hours: 8am to 4pm Email: [email protected] Traditional Territory of Simpcw 2 WELCOME The North Thompson Valley was once the busy highway of the First Nations people and, later, the fur traders, gold prospectors, ranchers and settlers. -

Jurisdictions Within the Thompson Watershed

Jurisdictions within the Tho!(mpson Watershed !( Valemount ´ RDFFG - H Quesnel Lake Hobson Lake Azure Lake !( Horsefly Lake Horsefly Clearwater Lake Murtle TNRD - B CRD - F Lake TNRD - A CRD - F CRD - G North Thompson River CRD - H Canim Lake Kinbasket 100 Mile House Clearwater Lake !( !( CRD - G CRD - L TNRD - O South Thompson River Bonaparte Bonaparte River Lake CSRD - F TNRD - E Clinton !( Adams CSRD - E Lake Revelstok e !( Thompson River Shuswap SLRD - B Lake Cache Kamloops Creek Lake CSRD - C !( !( TNRD - J !( Sicamous TNRD - P Chase !( (! Ashcroft !( Salmon ! !( Arm RDNO - F TNRD - I Kamloop s CSRD - D (!End erby Mabel ! Lake !( Logan Lak e Sp allumcheen TNRD - L !( !( Armstrong Nicola RDNO - B RDNO - C RDNO - D River Vernon Lumby RDNO - E Lytton Nicola !( !( !( Lake !( Cold stream !( Merritt !( Lak e Country TNRD - M Okanagan Lake TNRD - N Kelowna !( Peachland !( Summerland Harrison !( Lake (!Penticton !( ! Legend Regional District Abbreviation Key !( City, Town Administration Area Watershed CRD—Cariboo Regional District Roads Municip ality Bonap arte River FVRD—Fraser Valley Regional District The Secwep emc, Nlak a'p amux, Major Road IR Nicola River RDCK—Regional District of Central Kootenay Syilx and St'at'imc nations assert Minor Road Electoral Area North Thomp son River title and rights over d ifferent CSRD—Columbia Shuswap Regional District Park South Thomp son River p ortions of the Thomp son RDNO—Regional District of North Ok anagan Watershed Thomp son River RDOS—Regional District of Ok anagan Similk ameen 1:2,000,000 SLRD—Sq uamish-Lillooet Regional District TNRD—Thomp son Nicola Regional District 0 25 50 100 Kilometers. -

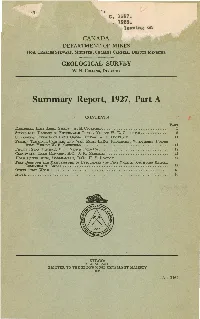

Summary Report, 1927, Part A

. ·. 1 ' . c. 1927 • . 1928. leaving on CANADA DEPARTMENT OF MINES HON. CHARLES STEWART, MINISTER; CHARLES CAMSELL, DEPUTY MINISTER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. H. COLLINS, DIRECTOR Summary Report, 1927, Part A CONTENTS PAGE DEZADEASH LAKE AREA, YUKON: W. E. COCKFIELD..... • . • . • . • . • • • • . • . 1 SILVER-LEAD DEPOSITS OF F1FTEENMILE CREEK, YUKON: w. E. COCKFIELD................ 8 SILVER-LEAD DEPOSITS OF RUDE CREEK, YUKON: W. E. COCKFIELD....................... 11 PUEBLO, TAMARACK-CARLISLE, AND WAR EAGLE-LERO! PROPERTIES, WHITEHORSE COPPER BELT, YUKON: w. E. COCKFIELD . .. .. .. .. .. • . • . • . 14 FINLAY RIVER DISTRICT, B.C.: VICTOR DOLMAGE........... .... .. ... .. • . •• . •. • . •• 19 CLEARWATER LAKE MAP-AREA, B.C.: J. R. MARSHALL..................................... 42 HoRN SILVER MINE, S1M1LKAMEEN, B.C.: H. S. BOSTOCK..................... 4.7 PEAT BoGs FOR THE MANUFACTURE OF PEAT LITTER AND PEAT MULL IN SouTRWEs'r BRITISH COLUMBIA: A. ANREP............................................................... 53 OTHER FIELD WORK ..... ... ••.... ' . .•... .. .. ' .•..••........ '.'.......................... 62 INDEX .•..•••••.•.•... ' . ••.•. •••..•.••.•• •• •.......... ..•... .. .. ..•.•.•..••...... ' . • . 63 OTTAWA F. A. ACLAND PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1928 No. 2162 CANADA DEPARTMENT OF MINES HON. CHARLES STEWART, MINISTER; CHARLES CAMSELL, DEPUTY MINISTER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. H. COLLINS, DIRECTOR Summary Report, 1927, Part A CONTENTS PAGE DEZADEASH LAKE AREA, YUKO ~: w. E. COCKFIELD ........ ......... .... • .............. -

REGION 3 - Thompson-Nicola

REGION 3 - Thompson-Nicola CONTACT INFORMATION Fish and Wildlife Regional Office Salmon Information: (250) 371-6200 1259 Dalhousie Dr Fisheries and Oceans Canada Kamloops BC V2C 5Z5 District Offices (DFO) Conservation Officer Service Kamloops: (250) 851-4950 Please call 1-877-952-7277 for recorded Lillooet: (250) 256-2650 information or to make an appointment at Salmon Arm: (250) 804-7000 any of the following Field Offices: Clearwater, Kamloops, Lillooet and Merritt R.A.P.P. Report All Poachers and Polluters Conservation Officer 24 Hour Hotline 1-877-952-RAPP (7277) STAY UP TO DATE: Cellular Dial #7277 Check website for in-season changes or Please refer to page 78 for more information closure dates for the 2021-2023 season rapp.bc.ca at: www.gov.bc.ca/FishingRegulations 7-1 7-4 5-15 WARNING Due to aeration projects, DANGEROUS THIN ICE & OPEN WATER may 5-13 3-46 exist on Bleeker, Horseshoe, Lodgepole, 7-2 Logan, Rose, Stake, Tulip & Walloper Lakes. 3-44 3-43 4-40 3-45 5-14 3-40 5-2 3-39 5-1 3-42 5-4 3-41 4-38 5-3 4 3-38 3-31 3-36 4-39 3-30 3-35 3-37 3-32 3-29 3-28 3-34 3-27 3-33 3-26 3-17 8-24 2-11 3-18 8-26 3-16 3-19 3-20 2-6 8-21 8-25 8-22 8-23 3-14 3-13 3-12 8-11 2-7 2-9 2-10 3-15 8-10 8-6 8-8 2-18 2-8 2-17 8-5 8-9 The Management Unit boundaries indicated on the2-19 map above are shown only as a reference8-7 to help anglers locate waters in the region. -

Canada's First Mountain Helicopter Rescue

CANADA’S FIRST MOUNTAIN HELICOPTER RESCUE SEPTEMBER 23, 1950 The Vancouver Sun Nanaimo Daily News (Sept. 25) 1 Recently Uncovered Mountain Rescue This recently uncovered event was possibly the first mountain rescue by helicopter in Canada. News of the rescue was broadcast over the radio and made newspapers across Canada. At the time, television broadcasting was only just beginning and very few people had TVs, but most everyone had radios. According to the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa Ontario, "It seems that you have uncovered Canada's first mountain helicopter rescue. We could not find other similar events that dated further back". Albert David Flowers was working as a Forestry Lookout-man on a remote mountain in Wells Gray Park (along with his son Gerald). It was a two-day trek to get there and that’s already from a remote homestead. Albert was tasked with getting out daily weather and fire reports. While there, he suffered an injury to his right leg that got progressively worse, so they radioed for a medical evacuation. Pilot D. K. “Deke” Orr of Okanagan Air Services was called away while flying for a mining company operating high in the mountains south of Hope BC. He arrived in a Bell 47B-3 helicopter, (CF-FZX) to fly Albert to the Kamloops hospital for treatment. It was lucky that his son Gerald was with him to clear an area for the helicopter to land. With his bad leg, Albert could not have done it. Gerald had just turned 15 and took several pictures of the rescue. -

Zanatta Winery and Vineyards

21_778834 bindex.qxp 4/27/06 6:56 PM Page 418 Index The Alaska Highway, 247–249 A-1 Last Minute Golf Hot Line AAA (American Automobile Alberta Gallery of Art (Edmon- (Vancouver), 88 Association), 36 ton), 3 Apex Rafting Company, 297 AARP, 29–30 Alcan Dragon Boat Festival Apex Resort (Penticton), 279 Abandoned Rails Trail, 300 (Vancouver), 58 Aquabus (Vancouver), 65 Abbottsford International Air Alcheringa Gallery (Victoria), Aquatic Centre (Vancouver), 89 Show (Vancouver), 59 111 Ark Resort (Strathcona Provin- Aberdeen Hills Golf Links Alert Bay, 9, 195, 197 cial Park), 194 (Kamloops), 266 Alice Lake Provincial Park, 220 Arrowsmith Golf and Country Abkhazi Garden (Victoria), 108 Alley Cat Rentals Club (near Qualicum Beach), Access America, 28 (Vancouver), 87 162 Accessible Journeys, 29 Alpenglow Aviation, 11, 304, Art and Soul Craft Gallery Accommodations 362 (Galiano Island), 128 best Alpine Rafting, 304 ArtCraft (Salt Spring Island), B&Bs and country inns, American Airlines, 32 123–124 14–15 American Airlines Vacations, 34 Art galleries and museums lodges, wilderness American Automobile Associa- Courtenay, 180 retreats and log-cabin tion (AAA), 36 Edmonton, 3, 335 resorts, 15–16 American Express, 39 Kamloops, 265 luxury hotels and resorts, Calgary, 320 Kelowna, 286 13–14 Edmonton, 334 Penticton, 277 surfing for, 31 traveler’s checks, 26 Prince George, 245 Active Pass, 128 Vancouver, 65 Prince Rupert, 229 Active vacations, 37–38 Victoria, 98 Tofino, 173 best, 6–7 American Foundation for the Williams Lake, 256 Adams River, 8 Blind, 29 -

^ = Partial Bathymetric Coverage * = Detailed Shoreline Only Page 1 of 19

^ = Partial Bathymetric Coverage * = Detailed Shoreline Only Inland Lakes British Columbia #3 Lake BC Alta Lake BC Baptiste Lake BC 103 Mile Lake BC Amanita Lake BC Barbara Lake BC 108 Mile Lake BC Ambrose Lake BC Bardolph Lake BC 130 Mile Lake BC Amor Lake BC Barnes Lake BC Abas Lake BC Anahim Lake BC Barsby Lake (Blind Lake) BC Abbott Lake BC Anderson Lake BC Barton Lake BC Abel Lake BC Andy Bailey Lake BC Basalt Lake BC Aberdeen Lake BC Angler Lake BC Battleship Lake BC Abrams Lake BC Angly Lake BC Baynes Lake BC Abruzzi Lake BC Angora Lake BC Beale Lake BC Abuntlet Lake BC Ant Lake BC Bear Creek Reservoir BC Academus Lake BC Antler Lake BC Bear Lake BC Acorn Lake BC Antoine Lake BC Bearhole Lake BC Aeroplane Lake BC Anutz Lake BC Bearpaw Lake BC Ahdatay Lake BC Anzac Lake BC Beartrack Lake BC Aid Lake BC Anzus Lake BC Beartrap Lake BC Aiken Lake BC Arctic Lake BC Beatrice Lake BC Aird Lake BC Armstrong Lake BC Beaux Yeux Lake BC Airline Lake BC Ash Lake BC Beaver Lake BC Alah Lake BC Atan Lake BC Beaverlodge Lake BC Albert Head Lagoon BC Atlin Lake BC/YT Beavertail Lake BC Albert Lake BC Atluck Lake BC Beck Lake BC Alces Lake BC Augier Lake BC Becker Lake BC Alex Graham Lake BC Azouzetta Lake BC Bedingfield Lake BC Alexis Lake BC Azuklotz Lake BC Bednesti Lake BC Aleza Lake BC Azure Lake BC Begbie Lake BC Alice Lake BC Babcock Lake BC Belcourt Lake BC Allan Lake BC Babette Lake BC Bells Lake BC Allendale Lake BC Badger Lake BC Ben Lake BC Alleyne Lake BC Baile Lake BC Bennett Lake BC/YT Allison Lake BC Balfour Lake BC Benny Lake BC -

The Experience Quarterly Currently Available Tours – As of April 2016

The Experience Quarterly Currently Available Tours – as of April 2016 800.667.9552 www.wellsgraytours.com Kamloops Vernon Kelowna Penticton Spend a fun afternoon with Wells Gray Tours, reconnect with your fellow travellers and enjoy refreshments. It’s our way of saying “Thank You” for your business. Please RSVP so that we can anticipate attendance. Penticton Kamloops Kelowna Vernon Monday, April 25th Tuesday, April 26th Wednesday, April 27th Thursday, April 28th 1:30 to 3:30 pm 1:30 to 3:30 pm 1:30 to 3:30 pm 1:30 to 3:30 pm Days Inn Conference St. Andrews Christ Evangelical Village Green Hotel Center Presbyterian Church Lutheran Church 4801 27th Street 152 Riverside Drive 1136 6th Avenue 2091 Gordon Drive Vernon, BC Penticton, BC Kamloops, BC Kelowna, BC 250-493-1255 250-374-0831 250-762-3435 250-545-9197 Staff News Come say farewell to Wendy Syms at the Kamloops Tea, Tuesday, April 26th and help celebrate her last day with Wells Gray Tours after 21 years! Stay Informed Wells Gray Tours provides tour policies on every tour itinerary. This information varies slightly for each tour and addresses specific items pertaining to each tour such as payments, discounts, cancella- tion policies, fare changes, insurance and activity levels. Please be sure to read this area carefully and call your local office with any questions. We want your tour experience to be exceptional from the moment you book. E-Newsletter Sign up for our monthly E-Newsletter to get access to newly released tours, travel tidbits and infor- mation on upcoming events.