Astrometric Radial Velocities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Color Chap 2.Cdr

Chapter 2 - Location and coordinates Updated 10 July 2006 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 +1 +2 +3 +4 Figure 2.1 A simple number line acts as a one-dimensional coordinate system. Each number describes the distance of a particular point-location from the origin, or zero. The unit of measure for the distance is arbitrary. 10 9 8 (4.5,7.5) 7 6 s i x a (3,5) - 5 y 4 3 (6,3) 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 x - axis Figure 2.2 Here is a simple x-y coordinate system with the coordinates of a few points shown as examples. Coordinates are given as an ordered pair of numbers, with the x-coordinate first. The origin is the lower left, at (0,0). The reference lines are the x and y axes. All grid lines are drawn parallel to the two reference lines. The purpose of the grid is to make it easier to make distance measurements between a location-point and the reference lines. 5 4 3 (2,3) 2 s 1 i x a (-2,0) - 0 y -1 -2 (1,-2) -3 -4 -5 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 x - axis Figure 2.3 A more general coordinate grid places the origin (0,0) at the center of the grid. The coordinates may have either positive or negative values. The sign merely indicates whether the point is left or right (x), or above or below (y) the axis. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

Sydney Observatory Night Sky Map September 2012 a Map for Each Month of the Year, to Help You Learn About the Night Sky

Sydney Observatory night sky map September 2012 A map for each month of the year, to help you learn about the night sky www.sydneyobservatory.com This star chart shows the stars and constellations visible in the night sky for Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra, Hobart, Adelaide and Perth for September 2012 at about 7:30 pm (local standard time). For Darwin and similar locations the chart will still apply, but some stars will be lost off the southern edge while extra stars will be visible to the north. Stars down to a brightness or magnitude limit of 4.5 are shown. To use this chart, rotate it so that the direction you are facing (north, south, east or west) is shown at the bottom. The centre of the chart represents the point directly above your head, called the zenith, and the outer circular edge represents the horizon. h t r No Star brightness Moon phase Last quarter: 08th Zero or brighter New Moon: 16th 1st magnitude LACERTA nd Deneb First quarter: 23rd 2 CYGNUS Full Moon: 30th rd N 3 E LYRA th Vega W 4 LYRA N CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES BOOTES VULPECULA SAGITTA PEGASUS DELPHINUS Arcturus Altair EQUULEUS SERPENS AQUILA OPHIUCHUS SCUTUM PISCES Moon on 23rd SERPENS Zubeneschamali AQUARIUS CAPRICORNUS E SAGITTARIUS LIBRA a Saturn Centre of the Galaxy Antares Zubenelgenubi t s Antares VIRGO s t SAGITTARIUS P SCORPIUS P e PISCESMICROSCOPIUM AUSTRINUS SCORPIUS Mars Spica W PISCIS AUSTRINUS CORONA AUSTRALIS Fomalhaut Centre of the Galaxy TELESCOPIUM LUPUS ARA GRUSGRUS INDUS NORMA CORVUS INDUS CETUS SCULPTOR PAVO CIRCINUS CENTAURUS TRIANGULUM -

THE CONSTELLATION MUSCA, the FLY Musca Australis (Latin: Southern Fly) Is a Small Constellation in the Deep Southern Sky

THE CONSTELLATION MUSCA, THE FLY Musca Australis (Latin: Southern Fly) is a small constellation in the deep southern sky. It was one of twelve constellations created by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman and it first appeared on a 35-cm diameter celestial globe published in 1597 in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of this constellation in a celestial atlas was in Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603. It was also known as Apis (Latin: bee) for two hundred years. Musca remains below the horizon for most Northern Hemisphere observers. Also known as the Southern or Indian Fly, the French Mouche Australe ou Indienne, the German Südliche Fliege, and the Italian Mosca Australe, it lies partly in the Milky Way, south of Crux and east of the Chamaeleon. De Houtman included it in his southern star catalogue in 1598 under the Dutch name De Vlieghe, ‘The Fly’ This title generally is supposed to have been substituted by La Caille, about 1752, for Bayer's Apis, the Bee; but Halley, in 1679, had called it Musca Apis; and even previous to him, Riccioli catalogued it as Apis seu Musca. Even in our day the idea of a Bee prevails, for Stieler's Planisphere of 1872 has Biene, and an alternative title in France is Abeille. When the Northern Fly was merged with Aries by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1929, Musca Australis was given its modern shortened name Musca. It is the only official constellation depicting an insect. Julius Schiller, who redrew and named all the 88 constellations united Musca with the Bird of Paradise and the Chamaeleon as mother Eve. -

Astronomical Detection of a Radioactive Molecule 26Alf in a Remnant of an Ancient Explosion

Astronomical detection of a radioactive molecule 26AlF in a remnant of an ancient explosion Tomasz Kamiński1*, Romuald Tylenda2, Karl M. Menten3, Amanda Karakas4, 5 6 5 6 1 Jan Martin Winters , Alexander A. Breier , Ka Tat Wong , Thomas F. Giesen , Nimesh A. Patel 1Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, MS 78, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 2Department for Astrophysics, N. Copernicus Astronomical Center, Rabiańska 8, 87-100, Toruń, Poland 3Max-Planck Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany 4Monash Centre for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, Monash University, VIC 3800, Australia 5IRAM, 300 rue de la Piscine, Domaine Universitaire de Grenoble, 38406, St. Martin d’Héres, France 6Laborastrophysik, Institut für Physik, Universität Kassel, Heinrich-Plett-Straße 40, Kassel, Germany *Correspondence to: [email protected] Decades ago, γ-ray observatories identified diffuse Galactic emission at 1.809 MeV (1-3) originating from β+ decays of an isotope of aluminium, 26Al, that has a mean-life time of 1.04 million years (4). Objects responsible for the production of this radioactive isotope have never been directly identified, owing to insufficient angular resolutions and sensitivities of the γ-ray observatories. Here, we report observations of millimetre-wave rotational lines of the isotopologue of aluminium monofluoride that contains the radioactive isotope (26AlF). The emission is observed toward CK Vul which is thought to be a remnant of a stellar merger (5-7). Our constraints on the production of 26Al combined with the estimates on the merger rate make it unlikely that objects similar to CK Vul are major producers of Galactic 26Al. -

Debian \ Amber \ Arco-Debian \ Arc-Live \ Aslinux \ Beatrix

Debian \ Amber \ Arco-Debian \ Arc-Live \ ASLinux \ BeatriX \ BlackRhino \ BlankON \ Bluewall \ BOSS \ Canaima \ Clonezilla Live \ Conducit \ Corel \ Xandros \ DeadCD \ Olive \ DeMuDi \ \ 64Studio (64 Studio) \ DoudouLinux \ DRBL \ Elive \ Epidemic \ Estrella Roja \ Euronode \ GALPon MiniNo \ Gibraltar \ GNUGuitarINUX \ gnuLiNex \ \ Lihuen \ grml \ Guadalinex \ Impi \ Inquisitor \ Linux Mint Debian \ LliureX \ K-DEMar \ kademar \ Knoppix \ \ B2D \ \ Bioknoppix \ \ Damn Small Linux \ \ \ Hikarunix \ \ \ DSL-N \ \ \ Damn Vulnerable Linux \ \ Danix \ \ Feather \ \ INSERT \ \ Joatha \ \ Kaella \ \ Kanotix \ \ \ Auditor Security Linux \ \ \ Backtrack \ \ \ Parsix \ \ Kurumin \ \ \ Dizinha \ \ \ \ NeoDizinha \ \ \ \ Patinho Faminto \ \ \ Kalango \ \ \ Poseidon \ \ MAX \ \ Medialinux \ \ Mediainlinux \ \ ArtistX \ \ Morphix \ \ \ Aquamorph \ \ \ Dreamlinux \ \ \ Hiwix \ \ \ Hiweed \ \ \ \ Deepin \ \ \ ZoneCD \ \ Musix \ \ ParallelKnoppix \ \ Quantian \ \ Shabdix \ \ Symphony OS \ \ Whoppix \ \ WHAX \ LEAF \ Libranet \ Librassoc \ Lindows \ Linspire \ \ Freespire \ Liquid Lemur \ Matriux \ MEPIS \ SimplyMEPIS \ \ antiX \ \ \ Swift \ Metamorphose \ miniwoody \ Bonzai \ MoLinux \ \ Tirwal \ NepaLinux \ Nova \ Omoikane (Arma) \ OpenMediaVault \ OS2005 \ Maemo \ Meego Harmattan \ PelicanHPC \ Progeny \ Progress \ Proxmox \ PureOS \ Red Ribbon \ Resulinux \ Rxart \ SalineOS \ Semplice \ sidux \ aptosid \ \ siduction \ Skolelinux \ Snowlinux \ srvRX live \ Storm \ Tails \ ThinClientOS \ Trisquel \ Tuquito \ Ubuntu \ \ A/V \ \ AV \ \ Airinux \ \ Arabian -

![Arxiv:0908.2624V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 18 Aug 2009](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1870/arxiv-0908-2624v1-astro-ph-sr-18-aug-2009-1111870.webp)

Arxiv:0908.2624V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 18 Aug 2009

Astronomy & Astrophysics Review manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Accurate masses and radii of normal stars: Modern results and applications G. Torres · J. Andersen · A. Gim´enez Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract This paper presents and discusses a critical compilation of accurate, fun- damental determinations of stellar masses and radii. We have identified 95 detached binary systems containing 190 stars (94 eclipsing systems, and α Centauri) that satisfy our criterion that the mass and radius of both stars be known to ±3% or better. All are non-interacting systems, so the stars should have evolved as if they were single. This sample more than doubles that of the earlier similar review by Andersen (1991), extends the mass range at both ends and, for the first time, includes an extragalactic binary. In every case, we have examined the original data and recomputed the stellar parameters with a consistent set of assumptions and physical constants. To these we add interstellar reddening, effective temperature, metal abundance, rotational velocity and apsidal motion determinations when available, and we compute a number of other physical parameters, notably luminosity and distance. These accurate physical parameters reveal the effects of stellar evolution with un- precedented clarity, and we discuss the use of the data in observational tests of stellar evolution models in some detail. Earlier findings of significant structural differences between moderately fast-rotating, mildly active stars and single stars, ascribed to the presence of strong magnetic and spot activity, are confirmed beyond doubt. We also show how the best data can be used to test prescriptions for the subtle interplay be- tween convection, diffusion, and other non-classical effects in stellar models. -

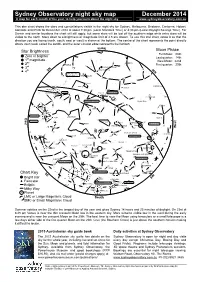

Sydney Observatory Night Sky Map December 2014 a Map for Each Month of the Year, to Help You Learn About the Night Sky

Sydney Observatory night sky map December 2014 A map for each month of the year, to help you learn about the night sky www.sydneyobservatory.com.au This star chart shows the stars and constellations visible in the night sky for Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra, Hobart, Adelaide and Perth for December 2014 at about 7:30 pm (Local Standard Time) or 8:30 pm (Local Daylight Savings Time). For Darwin and similar locations the chart will still apply, but some stars will be lost off the southern edge while extra stars will be visible to the north. Stars down to a brightness or magnitude limit of 4.5 are shown. To use this star chart, rotate it so that the direction you are facing (north, south, east or west) is shown at the bottom. The centre of the chart represents the point directly above your head, called the zenith, and the outer circular edge represents the horizon. h t r o N Star Brightness Moon Phase Full Moon: 06th Zero or brighterCapella st Last quarter: 14th 1 AURIGA magnitude Deneb New Moon: 22nd nd LACERTA 2 PERSEUS CYGNUSFirst quarter: 29th rd N Andromeda Galaxy 3 E th ANDROMEDA W 4 N M45 (Pleiades or Seven Sisters) TRIANGULUM Hamal ARIES VULPECULA PEGASUS TAURUS TAURUS Aldebaran AldebaranHyades PISCES Moon on 29th DELPHINUS SAGITTA First point of Aries EQUULEUS Mira Altair Betelgeuse Betelgeuse ORION CETUS ORION AQUARIUS Orion's belt M42 ERIDANUS E Rigel AQUILA a t s Saucepan SCULPTOR Fomalhaut CAPRICORNUS s t FORNAX Moon on 23rd PISCIS AUSTRINUS e PISCIS AUSTRINUS Mars P LEPUS W PHOENIX GRUS MICROSCOPIUM ERIDANUS SCUTUM Sirius -

A History of Star Catalogues

A History of Star Catalogues © Rick Thurmond 2003 Abstract Throughout the history of astronomy there have been a large number of catalogues of stars. The different catalogues reflect different interests in the sky throughout history, as well as changes in technology. A star catalogue is a major undertaking, and likely needs strong justification as well as the latest instrumentation. In this paper I will describe a representative sample of star catalogues through history and try to explain the reasons for conducting them and the technology used. Along the way I explain some relevent terms in italicized sections. While the story of any one catalogue can be the subject of a whole book (and several are) it is interesting to survey the history and note the trends in star catalogues. 1 Contents Abstract 1 1. Origin of Star Names 4 2. Hipparchus 4 • Precession 4 3. Almagest 5 4. Ulugh Beg 6 5. Brahe and Kepler 8 6. Bayer 9 7. Hevelius 9 • Coordinate Systems 14 8. Flamsteed 15 • Mural Arc 17 9. Lacaille 18 10. Piazzi 18 11. Baily 19 12. Fundamental Catalogues 19 12.1. FK3-FK5 20 13. Berliner Durchmusterung 20 • Meridian Telescopes 21 13.1. Sudlich Durchmusterung 21 13.2. Cordoba Durchmusterung 22 13.3. Cape Photographic Durchmusterung 22 14. Carte du Ciel 23 2 15. Greenwich Catalogues 24 16. AGK 25 16.1. AGK3 26 17. Yale Bright Star Catalog 27 18. Preliminary General Catalogue 28 18.1. Albany Zone Catalogues 30 18.2. San Luis Catalogue 31 18.3. Albany Catalogue 33 19. Henry Draper Catalogue 33 19.1. -

The National Optical Astronomy Observatory's Dark Skies and Energy Education Program Constellation at Your Fingertips: Crux 1

The National Optical Astronomy Observatory’s Dark Skies and Energy Education Program Constellation at Your Fingertips: Crux Grades: 3rd – 8th grade Overview: Constellation at Your Fingertips introduces the novice constellation hunter to a method for spotting the main stars in the constellation Crux, the Cross. Students will make an outline of the constellation used to locate the stars in Crux. This activity will engage children and first-time night sky viewers in observations of the night sky. The lesson links history, literature, and astronomy. The simplicity of Crux makes learning to locate a constellation and observing exciting for young learners. All materials for Globe at Night are available at http://www.globeatnight.org Purpose: Students will look for the faintest stars visible and record that data in order to compare data in Globe at Night across the world. In many cases, multiple night observations will build knowledge of how the “limiting” stellar magnitudes for a location change overtime. Why is this important to astronomers? Why do we see more stars in some locations and not others? How does this change over time? The focus is on light pollution and the options we have as consumers when purchasing outdoor lighting. The impact in our environment is an important issue in a child’s world. Crux is a good constellation to observe with young children. The constellation Crux (also known as the Southern Cross) is easily visible from the southern hemisphere at practically any time of year. For locations south of 34°S, Crux is circumpolar and thus always visible in the night sky.