Alternative Formats If You Require This Document in an Alternative Format, Please Contact: [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No.5 August 2015

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No.5 August 2015 DUNKELD LOURDES PILGRIMAGE 2015 - SOUVENIR EDITION Travellers return uplifted by prayerful pilgrimage The Rt. Rev. Stephen Robson Lourdes kick-started my faith Andrew Watson writes Over the years I have been asked to speak at Masses about my experience attending the Diocesan pilgrimage to Lourdes. This is something I have always been more than happy to do as it was an experience that profoundly changed my life. I hope that, in these columns, I can perhaps shine some “We said prayers for you” light on how that experience has actually continued to be of great value to me almost Photos by Lisa Terry three years since I last travelled with the Diocese of Dunkeld to Lourdes. Lourdes is not only a place that can strengthen and deepen the faith of the sick and elderly who go there, but impact the life of young Catholics in immeasurable ways. When I first signed up for Lourdes in 2008 I was 20 years old and just as nerv- ous as I was excited about making the pil- grimage there. This was the place where the Virgin Mary appeared to Bernadette and where so many miracles had occurred. ...in procession to the Grotto continued on page 6 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: News, views and coming events from around the diocese ©2015 DIOCESE OF DUNKELD - SCOTTISH CHARITY NO. SC001810 page 1 Saved Icon is Iconic for Saving Our Faith The story of the rescue of this statue is far from unique. Many medieval statues of our Lady, beloved by the people, we similarly rescued from the clutches of the Reform- ers. -

Lanarkshire Bus Guide

Lanarkshire Bus Guide We’re the difference. First Bus Lanarkshire Guide 1 First Bus is one of Britain’s largest bus operators. We operate around a fifth of all local bus services outside London. As a local employer, we employ 2,400 people across Greater Glasgow & Lanarkshire, as well as offering a range of positions, from becoming a qualified bus technician to working within our network team or human resources. Our 80 routes criss-cross Glasgow, supplied by 950 buses. Within Lanarkshire we have 483 buses on 11 routes, helping to bring the community together and enable everyday life. First Bus Lanarkshire Guide 2 Route Frequency From To From every East Kilbride. Petersburn 201 10 min Hairmyres Glasgow, From every Buchanan Bus Overtown 240 10 min Station From every North Cleland 241 10 min Motherwell From every Holytown/ Pather 242 20 min Maxim From every Forgewood North Lodge 244 hour From every Motherwell, Newarthill, 254 10 min West Hamilton St Mosshall St Glasgow, From every Hamilton Buchanan Bus 255 30 min Bus Station Station Glasgow, From every Hamilton Buchanan Bus 263 30 min Bus Station Station From every Hamilton Newmains/Shotts 266 6 min Bus Station Glasgow, From every Hamilton Buchanan Bus 267 10 min Bus Station Station First Bus Lanarkshire Guide 3 Fare Zone Map Carnbroe Calderbank Chapelhall Birkenshaw Burnhead Newhouse 266 to Glasgow 240 to Petersburn 242 NORTH 201 254 Uddingston Birkenshaw Dykehead Holytown LANARKSHIRE Shotts Burnhead LOCAL ZONE Torbothie Bellshill Newarthill 241 93 193 X11 Stane Flemington Hartwood Springhill -

Bishops Apologise, 'Shamed and Pained' by Abuse

St Andrews and Bishops Toal Edinburgh pilgrims and Robson at meet up with Grandparents’ Dunkeld’s at Mass at Carfin. Lourdes. Page 6 SUPPORTING 50 YEARS OF SCIAF, 1965-2015 Page 2 No 5634 VISIT YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER ONLINE AT WWW.SCONEWS.CO.UK Friday August 21 2015 | £1 Bishops’ Conference of Scotland president joined by members of the hierarchy to respond to the McLellan report on abuse handling PIC: PAUL McSHERRY Bishops apologise, ‘shamed and pained’ by abuse By Ian Dunn and added in his homily. “That this abuse of Scotland Moderator, said at the report’s secrecy with openness.’ ent system of monitoring the Church’s Daniel Harkins should have been carried out within the release that his commission had found safeguarding procedure outwith Church Church, and by priests and religious, there was ‘no doubt’ that ‘abuse of the Recommendations control and for the Church to pay for ARCHBISHOP Philip Tartaglia of takes that abuse to another level. Such most serious kind has taken place within Dr McKellan said his commission— counselling for survivors of abuse. Glasgow has offered a ‘profound actions are inexcusable and intolerable. the Church in Scotland.’ made up of a dozen people from a wide Dr McLellan said that all too often in apology’ on behalf of Scotland’s bish- The harm the perpetrators of abuse have Dr McLellan, a former head of HMI range of backgrounds including two the past ‘words had led nowhere’ but ops to those who have been abused caused is first and foremost to their vic- prison inspectorate who the bishops’ con- bishops—had eight key recommenda- these recommendations ‘can be meas- within the Church, and to those who tims, but it extends far beyond them, to ference asked to chair the independent tions the Scottish Church can follow to ured’ and the Church should be able to believe they have not been heard. -

Receive the Gospel of Christ Whose Herald You Have Become

Galloway Diocese Summer digital Edition June NEWSNEWS 2021 Receive the gospel of Christ whose herald you have become. Believe what you read Teach what you believe And practice what you teach. Congratulations to Kevin Rennie on his ordination to the Transitional Diaconate. More on centre pages The Bishop Writes The Holy Land Coordination pilgrimage did not go ahead this year and Bishop Nolan reflects that the Holy Land today is is very much the land of the suffering Christ. missed getting to Gaza this year. The lockdown Bishops visiting East Jerusalem prevented me from going there in January with the Holy I Land Coordination pilgrimage. This is a pilgrimage like no other. When the dozen or more bishops of the Coordination have their annual trip to the Holy Land it is not your usual pilgrimage. We are not there to visit the sites or the sacred shrines, we are not there to trace the footsteps of Jesus, we are not there to see ancient churches, we are there to see people. It is the Christian people and not the holy places that we go to visit. And that means we go to places the normal pilgrim would never visit, such as Gaza. It takes a bit of determination to get What is uplifting though is that we meet so many good to Gaza. There are a lot people. On my last visit in particular I was impressed by some of bureaucratic of the outstanding women we encountered. There was the obstacles to overcome. Jewish lady who told us all about the discrimination faced by So it is not easy to get the Palestinians in East Jerusalem. -

Lest We Forget

SCIAF sends PUPILS meet ST ANDREWS AND emergency aid to young royals EDINBURGH Gaza; hope raised at Glasgow pilgrimage to ceasefire holds. 2014 Games. Lourdes. Page 3 Page 4 Page 6 No 5581 VISIT YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER ONLINE AT WWW.SCONEWS.CO.UK Friday August 8 2014 | £1 By Ian Dunn THE Bishops of Scotland have LEST WE FORGET been at the forefront of commem- orative events that were held I across the country to mark the Church and state commemorate the centenary of centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. Britain’s entry into the First World War at services in Archbishop Philip Tartaglia of Glasgow attended a special service at Glasgow, Paisley, throughout Scotland and the UK Glasgow Cathedral on Monday where special guests included Prince Charles, Prime Minister David Cameron, First Minister Alex Salmond and Commonwealth heads of government, as well as UK and Irish politicians. A wreath-laying ceremony later took place at the cenotaph in Glasgow. In Paisley, Bishop John Keenan presided over a special lights out serv- ice at St Mirin’s Cathedral and Bishop Stephen Robson of Dunkeld preached at a solemn commemoration of the centenary of the beginning of the First World War in Dundee city centre. Glasgow Archbishop Tartaglia said it was a great privilege to be at the service in Glasgow. “I was glad to be present to represent the archdiocese at the Commonwealth Service in Glasgow Cathedral,” the archbishop said. “This city and this country gave up many young men to the terrible carnage that was World War One. -

Motherwell Pupils Gathered at Carfin

DON’T MISS OUT ON THE ULTIMATE CATHOLIC READING PACKAGE PAGE 8 No 5289 Sectarianism is back on the playing field Pages Justice Committee asked to take a hard line; Patrick Reilly on Neil Lennon verdict 3 &10 No 5434 www.sconews.co.uk Friday September 23 2011 | £1 ‘Bear joyful witness to the Gospel’ I Holy Father expresses this wish in message of thanks as Scotland marks the first anniversary of his state visit By Ian Dunn Archbishop Mario Conti of Glasgow celebrated Mass for Glasgow school students on the POPE Benedict XVI has told Papal visit anniversary in the vestments Catholics to bear joyful witness to Pope Benedict XVI wore to celebrate Mass the Gospel ‘which liberates our at Bellahouston Park on September 16 minds and enlightens our efforts to last year. PIC: PAUL McSHERRY live wisely and well, both as indi- viduals and as members of society’ The First Minister said that having a year on from his historic visit to been at Bellahouston for the Mass he Scotland and England. knew personally ‘just how powerful this The Holy Father’s message came as was for Scotland’s Catholic community.’ members of the Bishops’ Conference of “When I spoke to the Holy Father Scotland led young Catholics from personally that day I told him just how around the country in celebrations mark- much his visit meant to Scotland,” Mr ing the anniversary of the Holy Father’s Salmond said. “One particular image arrival on Scottish soil on September 16 sums up the day for me and I think last year and as celebrations were held at shows the feeling was well and truly Westminster Cathedral in London. -

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No. 23 June 2021 INSIDE THIS ISSUE - Tributes to the lifes of Bishop Vincent Logan, Mgr John Harty & Sr Deirdre O’Brien Substantial savings declared and a new parish levy is announced Lawside closes as strategic review looks to future of the diocese Addressing the clergy this week, Bishop Stephen revealed the perilous state of di- ocesan finances and the steps that are al- ready being taken to address the growing problem. As the impact of the pandemic becomes clearer, there are still many questions in the Church about the ‘new normal’ and, in par- ticular, the Church’s future after lockdown with attendances at Mass still limited, not only by social distancing, but also insecu- rities about the effects of the virus in the FOR SALE - DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY longer term. At an early stage during lock- down, Bishop Stephen made a financial appeal, his first in 42 years as a priest, for support for parishes and the wider Church community. With the churches closed, col- lections have fallen dramatically and new methods were needed to be set up for on- line giving and contactless payments in our With sights set on a fairer and more sus- “The Immaculate Heart of Mary Sis- churches. tainable system, Bishop Stephen said, “the ters are also to move, from Lawside to the Bishop Stephen said, “As you will know, Diocesan levy has not been touched for church house at St Mary’s Forebank, within the Diocese in recent years, for all sorts over twenty years and, due to the above- the city of Dundee.” of reasons, has been plunging deeper and mentioned increasing demands on finan- deeper into debt. -

SAINT AUGUSTINE’S PARISH CENTRE LINE DANCING GROUP OUR TWO FUNCTION SUITES AVAILABLE This Runs Every Friday in the Parish Centre from FOR

T HE P ARISH OF S AINT A UGUSTINE C OATBRIDGE ! S COTLAND 1892 - 2017 F IFTH S UNDAY OF E ASTER 1 4 M AY 2017 – F IRST H OLY C OMMUNIONS th 100 Anniversary of Fatima Apparitions th th Saturday 13 May marks the 100 Anniversary since Our Lady appeared in Fatima, Portugal. Pope Francis will be present to canonise two of the shepherd children who were privileged to see Our Lady and to receive her messages. The famous apparitions of the Virgin Mary took place during the First World War, in the summer of 1917. The inhabitants of this tiny village in the diocese of Leiria (Portugal) were mostly poor people, many of them small farmers who went out by day to tend their fields and animals. Children traditionally were assigned the task of herding the sheep. The three children who received the apparitions had been brought up in an atmosphere of genuine piety: Lucia dos Santos (ten years old) and her two younger cousins, Francisco and Jacinta. Together they tended the sheep and, with Lucy in charge, would often pray the Rosary kneeling in the open. In the summer of 1916 an Angel appeared to them several times and taught them a prayer to the Blessed Trinity. Exactly one hundred years ago, on Sunday, May 13, 1917, toward noon, a flash of lightning drew the attention of the children, and they saw a brilliant figure appearing over the trees of the Cova da Iria. The Lady asked them to pray for the conversion of sinners and an end to the war, and to come back every month, on the 13th. -

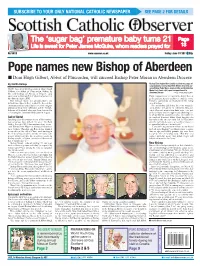

Pope Names New Bishop of Aberdeen � Dom Hugh Gilbert, Abbot of Pluscarden, Will Succeed Bishop Peter Moran in Aberdeen Diocese

SUBSCRIBE TO YOUR ONLY NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER SEE PAGE 2 FOR DETAILS No 5289 The ‘sugar bag’ premature baby turns 21 Page Life is sweet for Peter James McGuire, whom readers prayed for 13 No 5419 www.sconews.co.uk Friday June 10 2011 | 90p Pope names new Bishop of Aberdeen I Dom Hugh Gilbert, Abbot of Pluscarden, will succeed Bishop Peter Moran in Aberdeen Diocese By Martin Dunlop Bishop Elect Hugh Gilbert (main) received messages of congratulations from Cardinal Keith O’Brien (inset left), out- POPE Benedict XVI has named Dom Hugh going Bishop Peter Moran (inset middle) and Archbishop Gilbert, the abbot of Pluscarden Abbey, as Mario Conti (inset right) upon his appointment to the new bishop of Aberdeen Diocese and Aberdeen Diocese PICS: PAUL McSHERRY successor to Bishop Peter Moran who has led Hugh’s appointment is a loss to the abbey, there is the diocese since 2003. great gain for Aberdeen Diocese and the wider The Vatican made the announcement last Catholic community of Scotland in his being Saturday and Dom Gilbert, head of the Benedictine named bishop.” community at Pluscarden, has received the congrat- The archbishop added that the news would be ulations of his priestly colleagues and the Catholic ‘particularly welcomed in Aberdeen Diocese, bishops of Scotland, who now look forward to where Pluscarden has warm links with every part celebrating his Episcopal Ordination in August. of the territory and is recognised as a thriving cen- tre of spirituality, monastic practice and culture in Call of Christ the north of Scotland. Abbot Hugh has played a Speaking after the announcement of his nomina- key role in the success story that is Pluscarden tion as bishop, Dom Gilbert, 59, said: “The Holy over the last few decades, a period which has seen Father, Benedict XVI, has nominated me to suc- it expand its influence far and wide.’ ceed Bishop Peter Moran as bishop of Aberdeen. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Harris, A. (2016). Thérèse of Lisieux. In G. Atkins (Ed.), Making and Remaking Saints in Nineteenth-Century Britain (pp. 262-278). Manchester University Press, Manchester. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

21St July 11.30Am - MORNING MASS - ST

Saturday 20th July 5.30pm Vigil Mass - St. Bernadette’s Parish Priest: Fr. Mike Freyne MHM Day 16th Sunday Email: [email protected] Sunday 9.45am - Morning Mass, St. Fillan’s, Doune. for in 21st July 11.30am - MORNING MASS - ST. BERNADETTE’S Life Ordinary time Tel: 01259 213274 Mon 22nd July 9.30am - Morning Mass St. Bernadette’s Baingle Brae, Tullibody. FK10 2SG Tues 23rd July NO PARISH SERVICES Wednesday 9.30am - Morning Mass St. Bernadette’s. 24th July Thursday 9.30am - Morning Mass, St. Bernadette’s : 25th July Friday 26th July 7.00pm - Evening Mass, St Bernadette’s. 9.30am - Morning Mass,& Confessions St Bernadette’s Saturday 27th July 5.30pm - Vigil Mass, ST. BERNADETTE’S 17th Sunday Sunday 9.45am - Morning Mass, St. Fillan’s, Doune in 28th July 11.30am - MORNING MASS - ST. BERNADETTE’S Ordinary time FORTHCOMING EVENTS 4 Aug Mensal Fund Please remember in your prayers those who are sick: Margaret Mc’Intyre, 3.00pm National Pilgrimage John Craig, Margaret Byrne, Kathy Mc’Lauglin, Carly Mournian, Nellie Gallon, Sarah Jane Connelly, 1 Sept to Carfin Grotto Dave Kerr, Brendan Murphy, John Woods, Maurice Di Duca, Mary Gordon, Duncan Mc’Gregor, 2 Sept Parish Pastoral Council (Kathlean Clarke & Family, Peter-James, Gerard and Shaun-Joseph), Vincent McDaid, Regular Meetings Drs. Dianne & Mike Basquill, Margaret Stark, Roger Bray, John Mc’Niven, Fr. Brian Doran, Church Cleaning 10.30am Charles Roberson, Helen & Tommy Mc’Menemy, Fr. John Callaghan, John Smith SVDP: and all those in the various nursing homes. on Saturday Mornings Next meetings: 28th July & 11th Aug Please help! Knights of St. -

The Seal of the Confession Relics of St Thérèse Visit Scotland Summer

News from The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham in Scotland www.ordinariate.scot Summer 2019 Issue The Seal of the Confession in this▸ issue... PPROVED BY He decided to involve the APope Francis, the Church, as a “necessary Holy See has recently instrument” in this work of released a “Note on the salvation, and, in her, those importance of the internal whom He has chosen, called, forum and the inviolability and constituted as His ? Whithorn Cave of the Sacramental Seal”. ministers.” Pilgrimage It upholds the absolute inviolability According to the Note, Priests of the Seal of Confession, meaning should therefore “defend the Seal that priests can never be forced of Confession even to the point to reveal what they learn in the of shedding blood, both as an act Sacrament of Reconciliation. of loyalty to the penitent and as a witness -martyrdom - to the unique It states, “The inviolable secrecy of and universal salvation of Christ and Confession derives directly from revealed the Church”. ? Canonisation of Blessed John divine law and is rooted in the very Henry Newman nature of the sacrament, to the point of In an interview with Vatican admitting no exception in the ecclesial or, Radio, Cardinal Piacenza said that even less so, in the civil sphere. the goal in releasing the note is “to instil greater trust, especially in these “In the celebration of the Sacrament times, in penitents who come to ? Saved by her of Reconciliation, in fact, the very confess themselves... and ultimately to Guardian Angel essence of Christianity itself and of advance the cause of the sacrifice of the Church is encapsulated: the Son Christ who came to take away the sins of God became man to save us, and of the world.” Relics of St Thérèse visit Scotland HE RELICS of St Thérèse have been on an Tinternational pilgrimage since 1994, and are to ? Before .