Lecture 12: Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!E Following Article first Appeared in the Dutch Magazine “De Fagot”

THE DOUBLE REED 103 Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!e following article first appeared in the Dutch magazine “De Fagot”. It is reprinted here with permission in an English translation by James Aylward. Ed.) t used to be that orchestras, when they appointed a new second bassoon, would not take the best player, but a lesser one on instruction from the !rst bassoonist: the prima donna. "e !rst bassoonist would then blame the second for everything that went wrong. It was also not uncommon that the !rst bassoonist, when Ihe made a mistake, to shake an accusatory !nger at his colleague in clear view of the conductor. Nowadays it is clear that the second bassoon is not someone who is not good enough to play !rst, but a specialist in his own right. Jos de Lange and Ronald Karten, respectively second and !rst bassoonist from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra explain.) BASS VOICE Jos de Lange: What makes the second bassoon more interesting over the other woodwinds is that the bassoon is the bass. In the orchestra there are usually four voices: soprano, alto, tenor and bass. All the high winds are either soprano or alto, almost never tenor. !e "rst bassoon is o#en the tenor or the alto, and the second is the bass. !e bassoons are the tenor and bass of the woodwinds. !e second bassoon is the only bass and performs an important and rewarding function. One of the tasks of the second bassoon is to control the pitch, in other words to decide how high a chord is to be played. -

Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates Debut-G8 Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates Debut-G8

Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates debut-G8 Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates Debut-G8 Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates DEBUT-G5 Technical Exercise submission list Playing along to metronome is compulsory when indicated in the grade book. Exercises should commence after a 4-click metronome count in. Please ensure this is audible on the video recording. For chord exercises which are stipulated as being directed by the examiner, candidates must present all chords/voicings in all key centres. Candidates do not need to play these to click, but must be mindful of producing the chords clearly with minimal hesitancy between each. Note: Candidate should play all listed scales, arpeggios and chords in the key centres and positions shown. Debut Group A Group B Group C Scales (70 bpm) Chords Acoustic Riff 1. C major Open position chords (play all) To be played to backing track 2. E minor pentatonic 3. A minor pentatonic grade 1 Group A Group B Group C Scales (70 bpm) Chords (70 bpm) Acoustic Riff 1. C major 1. Powerchords To be played to backing track 2. A natural minor 2. Major Chords (play all) 3. E minor pentatonic 3. Minor Chords (play all) 4. A minor pentatonic 5. G major pentatonic Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates Debut-G8 grade 2 Group A Group B Group C Scales (80 bpm) Chords (80 bpm) Acoustic Riff 1. C major 1. Powerchords To be played to backing track 2. G Major 2. Major and minor Chords 3. E natural minor (play all) 4. A natural minor 3. Minor 7th Chords (play all) 5. -

Playing Harmonica with Guitar & Ukulele

Playing Harmonica with Guitar & Ukulele IT’S EASY WITH THE LEE OSKAR HARMONICA SYSTEM... SpiceSpice upup youryour songssongs withwith thethe soulfulsoulful soundsound ofof thethe harmonicaharmonica alongalong withwith youryour GuitarGuitar oror UkuleleUkulele playing!playing! Information all in one place! Online Video Guides Scan or visit: leeoskarquickguide.com ©2013-2016 Lee Oskar Productions Inc. - All Rights Reserved Major Diatonic Key labeled in 1st Position (Straight Harp) Available in 14 keys: Low F, G, Ab, A, Bb, B, C, Db, D, Eb, E, F, F#, High G Key of C MAJOR DIATONIC BLOW DRAW The Major Diatonic harmonica uses a standard Blues tuning and can be played in the 1st Position (Folk & Country) or the 2 nd Position (Blues, Rock/Pop Country). 1 st Position: Folk & Country Most Folk and Country music is played on the harmonica in the key of the blow (exhale) chord. This is called 1 st Position, or straight harp, playing. Begin by strumming your guitar / ukulele: C F G7 C F G7 With your C Major Diatonic harmonica Key of C MIDRANGE in its holder, starting from blow (exhale), BLOW try to pick out a melody in the midrange of the harmonica. DRAW Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do C Major scale played in 1st Position C D E F G A B C on a C Major Diatonic harmonica. 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 7 ©2013-2016 Lee Oskar Productions Inc. All Rights Reserved 2nd Position: Blues, Rock/Pop, Country Most Blues, Rock, and modern Country music is played on the harmonica in the key of the draw (inhale) chord. -

GRAMMAR of SOLRESOL Or the Universal Language of François SUDRE

GRAMMAR OF SOLRESOL or the Universal Language of François SUDRE by BOLESLAS GAJEWSKI, Professor [M. Vincent GAJEWSKI, professor, d. Paris in 1881, is the father of the author of this Grammar. He was for thirty years the president of the Central committee for the study and advancement of Solresol, a committee founded in Paris in 1869 by Madame SUDRE, widow of the Inventor.] [This edition from taken from: Copyright © 1997, Stephen L. Rice, Last update: Nov. 19, 1997 URL: http://www2.polarnet.com/~srice/solresol/sorsoeng.htm Edits in [brackets], as well as chapter headings and formatting by Doug Bigham, 2005, for LIN 312.] I. Introduction II. General concepts of solresol III. Words of one [and two] syllable[s] IV. Suppression of synonyms V. Reversed meanings VI. Important note VII. Word groups VIII. Classification of ideas: 1º simple notes IX. Classification of ideas: 2º repeated notes X. Genders XI. Numbers XII. Parts of speech XIII. Number of words XIV. Separation of homonyms XV. Verbs XVI. Subjunctive XVII. Passive verbs XVIII. Reflexive verbs XIX. Impersonal verbs XX. Interrogation and negation XXI. Syntax XXII. Fasi, sifa XXIII. Partitive XXIV. Different kinds of writing XXV. Different ways of communicating XXVI. Brief extract from the dictionary I. Introduction In all the business of life, people must understand one another. But how is it possible to understand foreigners, when there are around three thousand different languages spoken on earth? For everyone's sake, to facilitate travel and international relations, and to promote the progress of beneficial science, a language is needed that is easy, shared by all peoples, and capable of serving as a means of interpretation in all countries. -

10 - Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1

Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef Chapter 2. Bass Clef In this chapter you will: 1.Write bass clefs 2. Write some low notes 3. Match low notes on the keyboard with notes on the staff 4. Write eighth notes 5. Identify notes on ledger lines 6. Identify sharps and flats on the keyboard 7.Write sharps and flats on the staff 8. Write enharmonic equivalents date: 2.1 Write bass clefs • The symbol at the beginning of the above staff, , is an F or bass clef. • The F or bass clef says that the fourth line of the staff is the F below the piano’s middle C. This clef is used to write low notes. DRAW five bass clefs. After each clef, which itself includes two dots, put another dot on the F line. © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 10 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef 2.2 Write some low notes •The notes on the spaces of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom space are: A, C, E and G as in All Cows Eat Grass. •The notes on the lines of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom line are: G, B, D, F and A as in Good Boys Do Fine Always. 1. IDENTIFY the notes in the song “This Old Man.” PLAY it. 2. WRITE the notes and bass clefs for the song, “Go Tell Aunt Rhodie” Q = quarter note H = half note W = whole note © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 11 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. -

Use of Scale Modeling for Architectural Acoustic Measurements

Gazi University Journal of Science Part B: Art, Humanities, Design And Planning GU J Sci Part:B 1(3):49-56 (2013) Use of Scale Modeling for Architectural Acoustic Measurements Ferhat ERÖZ 1,♠ 1 Atılım University, Department of Interior Architecture & Environmental Design Received: 09.07.2013 Accepted:01.10.2013 ABSTRACT In recent years, acoustic science and hearing has become important. Acoustic design tests used in acoustic devices is crucial. Sound propagation is a complex subject, especially inside enclosed spaces. From the 19th century on, the acoustic measurements and tests were carried out using modeling techniques that are based on room acoustic measurement parameters. In this study, the effects of architectural acoustic design of modeling techniques and acoustic parameters were investigated. In this context, the relationships and comparisons between physical, scale, and computer models were examined. Key words: Acoustic Modeling Techniques, Acoustics Project Design, Acoustic Parameters, Acoustic Measurement Techniques, Cavity Resonator. 1. INTRODUCTION (1877) “Theory of Sound”, acoustics was born as a science [1]. In the 20th century, especially in the second half, sound and noise concepts gained vast importance due to both A scientific context began to take shape with the technological and social advancements. As a result of theoretical sound studies of Prof. Wallace C. Sabine, these advancements, acoustic design, which falls in the who laid the foundations of architectural acoustics, science of acoustics, and the use of methods that are between 1898 and 1905. Modern acoustics started with related to the investigation of acoustic measurements, studies that were conducted by Sabine and auditory became important. Therefore, the science of acoustics quality was related to measurable and calculable gains more and more important every day. -

Day 17 AP Music Handout, Scale Degress.Mus

Scale Degrees, Chord Quality, & Roman Numeral Analysis There are a total of seven scale degrees in both major and minor scales. Each of these degrees has a name which you are required to memorize tonight. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 & w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic A triad can be built upon each scale degree. w w w w & w w w w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic The quality and scale degree of the triads is shown by Roman numerals. Captial numerals are used to indicate major triads with lowercase numerals used to show minor triads. Diminished triads are lowercase with a "degree" ( °) symbol following and augmented triads are capital followed by a "plus" ( +) symbol. Roman numerals written for a major key look as follows: w w w w & w w w w w w w w CM: wI (M) iiw (m) wiii (m) IV (M) V (M) vi (m) vii° (dim) I (M) EVERY MAJOR KEY FOLLOWS THE PATTERN ABOVE FOR ITS ROMAN NUMERALS! Because the seventh scale degree in a natural minor scale is a whole step below tonic instead of a half step, the name is changed to subtonic, rather than leading tone. Leading tone ALWAYS indicates a half step below tonic. Notice the change in the qualities and therefore Roman numerals when in the natural minor scale. -

An App to Find Useful Glissandos on a Pedal Harp by Bill Ooms

HarpPedals An app to find useful glissandos on a pedal harp by Bill Ooms Introduction: For many years, harpists have relied on the excellent book “A Harpist’s Survival Guide to Glisses” by Kathy Bundock Moore. But if you are like me, you don’t always carry all of your books with you. Many of us now keep our music on an iPad®, so it would be convenient to have this information readily available on our tablet. For those of us who don’t use a tablet for our music, we may at least have an iPhone®1 with us. The goal of this app is to provide a quick and easy way to find the various pedal settings for commonly used glissandos in any key. Additionally, it would be nice to find pedal positions that produce a gliss for common chords (when possible). Device requirements: The application requires an iPhone or iPad running iOS 11.0 or higher. Devices with smaller screens will not provide enough space. The following devices are recommended: iPhone 7, 7Plus, 8, 8Plus, X iPad 9.7-inch, 10.5-inch, 12.9-inch Set the pedals with your finger: In the upper window, you can set the pedal positions by tapping the upper, middle, or lower position for flat, natural, and sharp pedal position. The scale or chord represented by the pedal position is shown in the list below the pedals (to the right side). Many pedal positions do not form a chord or scale, so this window may be blank. Often, there are several alternate combinations that can give the same notes. -

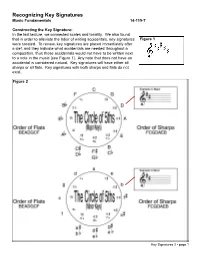

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T Constructing the Key Signature: In the last lecture, we connected scales and tonality. We also found that in order to alleviate the labor of writing accidentals, key signatures Figure 1 were created. To review, key signatures are placed immediately after a clef, and they indicate what accidentals are needed throughout a composition, thus those accidentals would not have to be written next to a note in the music [see Figure 1]. Any note that does not have an accidental is considered natural. Key signatures will have either all sharps or all flats. Key signatures with both sharps and flats do not exist. Figure 2 Key Signatures 2 - page 1 The Circle of 5ths: One of the easiest ways of recognizing key signatures is by using the circle of 5ths [see Figure 2]. To begin, we must simply memorize the key signature without any flats or sharps. For a major key, this is C-major and for a minor key, A-minor. After that, we can figure out the key signature by following the diagram in Figure 2. By adding one sharp, the key signature moves up a perfect 5th from what preceded it. Therefore, since C-major has not sharps or flats, by adding one sharp to the key signa- ture, we find G-major (G is a perfect 5th above C). You can see this by moving clockwise around the circle of 5ths. For key signatures with flats, we move counter-clockwise around the circle. Since we are moving “backwards,” it makes sense that by adding one flat, the key signature is a perfect 5th below from what preceded it. -

Key Relationships in Music

LearnMusicTheory.net 3.3 Types of Key Relationships The following five types of key relationships are in order from closest relation to weakest relation. 1. Enharmonic Keys Enharmonic keys are spelled differently but sound the same, just like enharmonic notes. = C# major Db major 2. Parallel Keys Parallel keys share a tonic, but have different key signatures. One will be minor and one major. D minor is the parallel minor of D major. D major D minor 3. Relative Keys Relative keys share a key signature, but have different tonics. One will be minor and one major. Remember: Relatives "look alike" at a family reunion, and relative keys "look alike" in their signatures! E minor is the relative minor of G major. G major E minor 4. Closely-related Keys Any key will have 5 closely-related keys. A closely-related key is a key that differs from a given key by at most one sharp or flat. There are two easy ways to find closely related keys, as shown below. Given key: D major, 2 #s One less sharp: One more sharp: METHOD 1: Same key sig: Add and subtract one sharp/flat, and take the relative keys (minor/major) G major E minor B minor A major F# minor (also relative OR to D major) METHOD 2: Take all the major and minor triads in the given key (only) D major E minor F minor G major A major B minor X as tonic chords # (C# diminished for other keys. is not a key!) 5. Foreign Keys (or Distantly-related Keys) A foreign key is any key that is not enharmonic, parallel, relative, or closely-related. -

Introduction to Music Theory

Introduction to Music Theory This pdf is a good starting point for those who are unfamiliar with some of the key concepts of music theory. Reading musical notation Musical notation (also called a score) is a visual representation of the pitched notes heard in a piece of music represented by dots over a set of horizontal staves. In the top example the symbol to the left of the notes is called a treble clef and in the bottom example is called a bass clef. People often like to use a mnemonic to help remember the order of notes on each clef, here is an example. Intervals An interval is the difference in pitch between two notes as defined by the distance between the two notes. The easiest way to visualise this distance is by thinking of the notes on a piano keyboard. For example, on a C major scale, the interval from C to E is a 3rd and the interval from C to G is a 5th. Click here for some more interval examples. It is also common for an increase by one interval to be called a halfstep, or semitone, and an increase by two intervals to be called a whole step, or tone. Joe ReesJones, University of York, Department of Electronics 19/08/2016 Major and minor scales A scale is a set of notes from which melodies and harmonies are constructed. There are two main subgroups of scales: Major and minor. The type of scale is dependant on the intervals between the notes: Major scale Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semitone Minor scale Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone For example (by visualising a keyboard) the notes in C Major are: CDEFGAB, and C Minor are: CDE♭FGA♭B♭. -

Unicode Technical Note: Byzantine Musical Notation

1 Unicode Technical Note: Byzantine Musical Notation Version 1.0: January 2005 Nick Nicholas; [email protected] This note documents the practice of Byzantine Musical Notation in its various forms, as an aid for implementors using its Unicode encoding. The note contains a good deal of background information on Byzantine musical theory, some of which is not readily available in English; this helps to make sense of why the notation is the way it is.1 1. Preliminaries 1.1. Kinds of Notation. Byzantine music is a cover term for the liturgical music used in the Orthodox Church within the Byzantine Empire and the Churches regarded as continuing that tradition. This music is monophonic (with drone notes),2 exclusively vocal, and almost entirely sacred: very little secular music of this kind has been preserved, although we know that court ceremonial music in Byzantium was similar to the sacred. Byzantine music is accepted to have originated in the liturgical music of the Levant, and in particular Syriac and Jewish music. The extent of continuity between ancient Greek and Byzantine music is unclear, and an issue subject to emotive responses. The same holds for the extent of continuity between Byzantine music proper and the liturgical music in contemporary use—i.e. to what extent Ottoman influences have displaced the earlier Byzantine foundation of the music. There are two kinds of Byzantine musical notation. The earlier ecphonetic (recitative) style was used to notate the recitation of lessons (readings from the Bible). It probably was introduced in the late 4th century, is attested from the 8th, and was increasingly confused until the 15th century, when it passed out of use.