Imagery Erom the Technology of the Btdwstrial Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 2013

ARTICLE Part II: Reproductions of Drawings and Paintings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors Section B: Collections and Selections Part III: Commercial Engravings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors William Blake and His Circle: Part IV: Catalogues and Bibliographies A Checklist of Publications and Section A: Individual Catalogues Section B: Collections and Selections Discoveries in 2013 Part V: Books Owned by William Blake the Poet Part VI: Criticism, Biography, and Scholarly Studies By G. E. Bentley, Jr. Division II: Blake’s Circle Blake Publications and Discoveries in 2013 with the assistance of Hikari Sato for Japanese publications and of Fernando 1 The checklist of Blake publications recorded in 2013 in- Castanedo for Spanish publications cludes works in French, German, Japanese, Russian, Span- ish, and Ukrainian, and there are doctoral dissertations G. E. Bentley, Jr. ([email protected]) is try- from Birmingham, Cambridge, City University of New ing to learn how to recognize the many styles of hand- York, Florida State, Hiroshima, Maryland, Northwestern, writing of a professional calligrapher like Blake, who Oxford, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Voronezh used four distinct hands in The Four Zoas. State, and Wrocław. The Folio Society facsimile of Blake’s designs for Gray’s Poems and the detailed records of “Sale Editors’ notes: Catalogues of Blake’s Works 1791-2013” are likely to prove The invaluable Bentley checklist has grown to the point to be among the most lastingly valuable of the works listed. where we are unable to publish it in its entirety. All the material will be incorporated into the cumulative Gallica “William Blake and His Circle” and “Sale Catalogues of William Blake’s Works” on the Bentley Blake Collection 2 A wonderful resource new to me is Gallica <http://gallica. -

William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: from Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1977 William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W. Winkleblack Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Winkleblack, Robert W., "William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence" (1977). Masters Theses. 3328. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3328 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. �S"Date J /_'117 Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ��--��- Date Author pdm WILLIAM BLAKE'S SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE: - FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE TO WISE INNOCENCE (TITLE) BY Robert W . -

Alicia Ostriker, Ed., William Blake: the Complete Poems

REVIEW Alicia Ostriker, ed., William Blake: The Complete Poems John Kilgore Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue 4, Spring 1979, pp. 268-270 268 psychological—carried by Turner's sublimely because I find myself in partial disagreement with overwhelming sun/god/king/father. And Paulson argues Arnheim's contention "that any organized entity, in that the vortex structure within which this sun order to be grasped as a whole by the mind, must be characteristically appears grows as much out of translated into the synoptic condition of space." verbal signs and ideas ("turner"'s name, his barber- Arnheim seems to believe, not only that all memory father's whorled pole) as out of Turner's early images of temporal experiences are spatial, but that sketches of vortically copulating bodies. Paulson's they are also synoptic, i.e. instantaneously psychoanalytical speculations are carried to an perceptible as a comprehensive whole. I would like extreme by R. F. Storch who argues, somewhat to suggest instead that all spatial images, however simplistically, that Shelley's and Turner's static and complete as objects, are experienced tendencies to abstraction can be equated with an temporally by the human mind. In other works, we alternation between aggression toward women and a "read" a painting or piece of sculpture or building dream-fantasy of total love. Storch then applauds in much the same way as we read a page. After Constable's and Wordsworth's "sobriety" at the isolating the object to be read, we begin at the expense of Shelley's and Turner's overly upper left, move our eyes across and down the object; dissociated object-relations, a position that many when this scanning process is complete, we return to will find controversial. -

In Harmony Lambeth an Evaluation Executive Summary

In Harmony Lambeth An Evaluation Executive Summary Kirstin Lewis Feyisa Demie Lynne Rogers Contents Page Section 1: Introduction 3 Section 2: Methodological approach for evaluation of the project 4 Section 3: The impact of In Harmony on achievement 5 Section 4: The impact of In Harmony in improving musical knowledge: 7 Empirical evidence Section 5: The impact of in Harmony on musical knowledge and 8 improving well being: Evidence from tracking pupils Section 6: Pastoral impact on Children 14 Section 7: Impact on community aspiration and cohesion 15 Section 8: Impact on school life 17 Section 9: Conclusions 18 Section 10. Recommendations 19 1 Acknowledgements This evaluation was commissioned by the Lambeth Music Service in consultation with the London Borough of Lambeth and the DfE. The project evaluation partners are the Lambeth Research and Statistics Unit and the Institute of Education (IOE), University of London. The project was lead and coordinated by Feyisa Demie on behalf of Lambeth Council. In the Lambeth Children and Young People’s Service, many people were involved in all stages of evaluation. We extend our particular thanks to: • Brendon Le Page, Head of Lambeth Music Service and Director, In Harmony Lambeth, and his team, for full support during the evaluation period and comments to the draft report. • Donna Pieters, In Harmony Project Coordinator/ Amicus Horizon, for help and support during the focus groups and interviews. • Phyllis Dunipace, Executive Director of Children and Young People’s Service and Chris Ashton, Divisional Director, for their support and encouragement throughout the project. • Rebecca Butler for help in data collection and analysis of the In Harmony assessment data and pupil questionnaire survey results. -

The Bravery of William Blake

ARTICLE The Bravery of William Blake David V. Erdman Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 10, Issue 1, Summer 1976, pp. 27-31 27 DAVID V. ERDMAN The Bravery of William Blake William Blake was born in the middle of London By the time Blake was eighteen he had been eighteen years before the American Revolution. an engraver's apprentice for three years and had Precociously imaginative and an omnivorous reader, been assigned by his master, James Basire, to he was sent to no school but a school of drawing, assist in illustrating an antiquarian book of at ten. At fourteen he was apprenticed as an Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain. Basire engraver. He had already begun writing the sent Blake into churches and churchyards but exquisite lyrics of Poetioal Sketches (privately especially among the tombs in Westminster Abbey printed in 1783), and it is evident that he had to draw careful copies of the brazen effigies of filled his mind and his mind's eye with the poetry kings and queens, warriors and bishops. From the and art of the Renaissance. Collecting prints of drawings line engravings were made under the the famous painters of the Continent, he was happy supervision of and doubtless with finishing later to say that "from Earliest Childhood" he had touches by Basire, who signed them. Blake's dwelt among the great spiritual artists: "I Saw & longing to make his own original inventions Knew immediately the difference between Rafael and (designs) and to have entire charge of their Rubens." etching and engraving was yery strong when it emerged in his adult years. -

William Blake 1 William Blake

William Blake 1 William Blake William Blake William Blake in a portrait by Thomas Phillips (1807) Born 28 November 1757 London, England Died 12 August 1827 (aged 69) London, England Occupation Poet, painter, printmaker Genres Visionary, poetry Literary Romanticism movement Notable work(s) Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Four Zoas, Jerusalem, Milton a Poem, And did those feet in ancient time Spouse(s) Catherine Blake (1782–1827) Signature William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[1] His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[2] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3] Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham[4] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[5] or "Human existence itself".[6] Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings William Blake 2 and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic",[7] for its large appearance in the 18th century. -

And Edward Young's Book Of

MINUTE PARTICULAR Blake’s “The Tyger” and Edward Young’s Book of Job Robert F. Gleckner Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 21, Issue 3, Winter 1987/1988, pp. 99-101 WINTER 1987-88 BLAKE/AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY PAGE 99 Blake's "The Tyger" and Edward Youngs burden of God's angry reproof ofJob is the reaffirming of the latter's littleness and incapacity, culminating in Book of Job the advice to "abase" the proud "and bring him low. " 3 In any discussion of Blake's speaker, then, Young's foot- Robert F. Gleckner note is at least an intriguing gloss on the biblical pas- sage. If sublime interrogation is a manifestation of "majesty incensed, " then the speaker of' 'The Tyger, " in Of all of Blake's shorter poems "The Tyger" has received, his usurpation of this rhetorical mode, is presumptuous by far, the most attention, an often confusing array of beyond words, asking "the guilty a proper question" so complementary (as well as contradictory) interpreta- that the guilty will, "in effect, pass sentence on him- tions, source studies, and prosodic analyses. Of those, self." On the other hand, Blake may have found in the seeking hither and yon for tigers of various sorts has Youn~'s idea of "bidding a person execute himself" the produced especially little that is illuminating about germ1nal principle of the structure of "The Tyger," in Blake's possible sources for the poem as distinct from which Blake, as creator, quite literally allows his speaker, sources for his choice of animal or for its (still uneasily by questioning, to convict himself before the reader's received) portrait in the illustration. -

The Prophetic Books of William Blake : Milton

W. BLAKE'S MILTON TED I3Y A. G.B.RUSSELL and E.R.D. MACLAGAN J MILTON UNIFORM WirH THIS BOOK The Prophetic Books of W. Blake JERUSALEM Edited by E. R. D. Maclagan and A. G. B. Russell 6s. net : THE PROPHETIC BOOKS OF WILLIAM BLAKE MILTON Edited by E. R. D. MACLAGAN and A. G. B. RUSSELL LONDON A. H. BULLEN 47, GREAT RUSSELL STREET 1907 CHISWICK PRESS : CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. INTRODUCTION. WHEN, in a letter to his friend George Cumberland, written just a year before his departure to Felpham, Blake lightly mentions that he had passed " nearly twenty years in ups and downs " since his first embarkation upon " the ocean of business," he is simply referring to the anxiety with which he had been continually harassed in regard to the means of life. He gives no hint of the terrible mental conflict with which his life was at that time darkened. It was more actually then a question of the exist- ence of his body than of the state of his soul. It is not until several years later that he permits us to realize the full significance of this sombre period in the process of his spiritual development. The new burst of intelle6tual vision, accompanying his visit to the Truchsessian Pi6lure Gallery in 1804, when all the joy and enthusiasm which had inspired the creations of his youth once more returned to him, gave him courage for the first time to face the past and to refledl upon the course of his deadly struggle with " that spe6lrous fiend " who had formerly waged war upon his imagination. -

David Punter, Ed., William Blake: Selected Poetry and Prose

REVIEW Stanley Kunitz, ed., The Essential Blake; Michael Mason, ed., William Blake; David Punter, ed., William Blake: Selected Poetry and Prose E. B. Murray Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 24, Issue 4, Spring 1991, pp. 145-153 Spring 1991 BLAKE/AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY Not so the Oxford Authors and Rout- As we know, and contrary to Mason's ledge Blakes. They do have some pre- implications, Blake felt his illumina- REVIEWS tensions and they may not be tions an integral part of his composite altogether harmless. Michael Mason is art, going so far as to applaud himself initially concerned with telling us what (in the third person) for having in- he does not do in his edition. He does vented "a method of Printing which Stanley Kunitz, ed. The Es not include An Island in the Moon, The combines the Painter and Poet" and, in sential Blake. New York: Book of Ahania, or The FourZoas. He an earlier self-evaluation, he bluntly The Ecco Press, 1987. 92 does not follow a chronological order asserts, through a persona, that those pp. $5.00 paper; Michael in presenting Blake's texts; he does not (pace Mason) who will not accept and Mason, ed. William Blake. provide deleted or alternative read- pay highly for the illuminated writings ings; he does not provide the illumina- he projected "will be ignorant fools Oxford: Oxford University tions or describe them; he does not and will not deserve to live." Ipse dixit. Press, 1988. xxvi + 601 pp. summarize the content of Blake's works The poet/artist is typically seconded $45.00 cloth/$15.95 paper; nor does he explicate Blake's mythol- by his twentieth-century editors, who, David Punter, ed. -

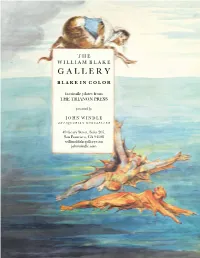

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected] -

Microfilms Internationa! 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Title/Author: the Spider and the Fly by Mary Howitt with Illustrations by Tony Diterlizzi

Students Achievement Partners Sample The Spider and The Fly Recommended for Grade 1 Title/Author: The Spider and The Fly by Mary Howitt with illustrations by Tony DiTerlizzi Suggested Time: 5 Days (five 20-minute sessions) Common Core grade-level ELA/Literacy Standards: RI.1.1, RI.1.2, RI.1.4, RI.1.6, RI.1.7; W.1.2, W.1.8; SL1.1, SL.1.2, SL.1.5; L.1.4 Lesson Objective: Students will listen to an illustrated narrative poem read aloud and use literacy skills (reading, writing, discussion and listening) to understand the central message of the poem. Teacher Instructions: Before the Lesson: 1. Read the Key Understandings and the Synopsis below. Please do not read this to the students. This is a description to help you prepare to teach the book and be clear about what you want your children to take away from the work. Key Understandings: How does the Spider trick the Fly into his web? The Spider uses flattery to trick the Fly into his web. What is this story trying to teach us? Don’t let yourself be tricked by sweet, flattering words. Page 1 of 16 Students Achievement Partners Sample The Spider and The Fly Recommended for Grade 1 Synopsis This is an illustrated version of the well-known poem about a cunning spider and a little fly. The Spider tries to lure the Fly into his web, promising interesting things to see, a comfortable bed, and treats from his pantry. At first the Fly, who has been told it is dangerous to go into the Spider’s parlor, refuses.