Foundational Thoughts 人間佛教論文選要

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academic Catalog Cover Placeholder 2020- 2021

ACADEMIC CATALOG COVER PLACEHOLDER 2020- 2021 2020 • 2021 Fall 2020, Spring 2021, Summer 2021 ACADEMIC CATALOG University of the West has made every effort to ensure the information in this catalog and other published materials is accurate. University of the West reserves the right to change policies, tuition, fees, and other information in this catalog, with prior approval from the WASC Senior College and University Commission (WSCUC) where applicable. University of the West strives to inform students and stakeholders of changes in a timely fashion, but reserves the right to make changes without notice. University of the West is a private, non-profit, WSCUC-accredited campus founded by and affiliated with the Taiwan-based Buddhist order of Fo Guang Shan. The University of the West name, abstract lotus logo, and calligraphic logo are copyrighted to the university. Additional information is available at our website, www.uwest.edu. University of the West does not discriminate on the basis of sex, gender, age, race, color, religion, status as a veteran, physical disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, and/or national and ethnic origin in its educational programs, student activities, 1409 Walnut Grove Avenue, Rosemead, CA 91770 employment, or admission policies, in the administration of its scholarship and loan programs, or in any other school- Telephone 626.571.8811 administered programs. This policy complies with requirements of the Internal Revenue Service Procedure 321-1, Title VI of the Fax 626.571.1413 Civil Rights Act, and Title IX of the 1972 Educational Amendments Email [email protected] as amended and enforced by the Department of Health and Human Services. -

BUDDHISM, MEDITATION, and the NEGOTIATION of the PUBLIC SPHERE by Leana Marie Rudolph a Capstone Project Submitted for Graduatio

BUDDHISM, MEDITATION, AND THE NEGOTIATION OF THE PUBLIC SPHERE By Leana Marie Rudolph A capstone project submitted for Graduation with University Honors May 20, 2021 University Honors University of California, Riverside APPROVED Dr. Matthew King Department of Religious Studies Dr. Richard Cardullo, Howard H Hays Jr. Chair University Honors ABSTRACT This capstone serves to map and gather the oral histories of formerly undocumented Buddhist communities pertaining to their lived experiences in the Inland Empire. The ethnographic fieldwork conducted of 11 sites over the period of 12 months explored the intersection of diaspora, economy, and religious affiliation. This research begins to explore this junction by undertaking a qualitative and quantitative study that will map Buddhist life in the Inland Empire today. It will include interviews, providing oral histories, and will be accessible through a GIS map, helping Religious Studies and Anthropologist scholars to locate these sites and have background information on these locations. The Inland Empire represents many heavily populated, post-agricultural, and manufacturing areas in America today, which since the 1970s and especially since 2008 has suffered from many economic and social crises related to suburban poverty, as well as waves of demographic changes. Taking the Inland Empire as a petri dish for broader trends at the intersection of religion, economy, and the social in the American public sphere today, this capstone project hopes to determine how Buddhism forms at these intersections, what new stories about life in the Inland Empire Buddhist sites and communities help illuminate, and what forms of digital interfacing best brings anthropological analyses to the publics it examines. -

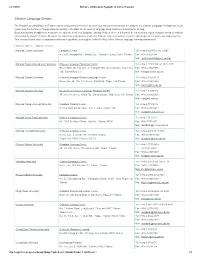

Chinese Language Centers

24/1/2015 Ministry of Education Republic of China (Taiwan) Chinese Language Centers The Republic of China(ROC) on Taiwan has for many years been home to numerous institutions devoted to the study of the Chinese Language. Perhaps this is one reason why the number of foreign students coming to the ROC for all levels of language study has been increasing for so long. Students find that in addition to being able to enjoy the benifits of language training facilities, there is a much to be learned from experiencing the blend of tradition and modernity found in Taiwan. Students can simultaneously observe traditional Chinese culture as well as enjoy the advantages of a modern, developed society. This, combined with ease of association with native speakers, is enough to make the ROC a fine Chinese language learning environment. Listing of Chinese Language Centers National Central University Language Center Tel: +88634227151 ext. 33807 No. 300, Jhongda Rd. , Jhongli City , Taoyuan County 32001, Taiwan Fax: +88634255384 Mail: mailto:[email protected] National Taipei University of Education Chinese Language Education Center Tel: +886227321104 ext.2025, 3331 Room 700C, No.134, Sec. 2, Heping E. Rd., Daan District, Taipei City Fax: +886227325950 106, Taiwan(R.O.C.) Mail: [email protected] National Taiwan University Chinese Language Division Language Center Tel: +886233663417 Room 222, 2F , No. 170, Sec.2, XinHai Rd, Taipei, 106,Taiwan Fax: +886283695042 Mail: [email protected] National Taiwan University International Chinese Language Program (ICLP) Tel: +886223639123 4F., No.170, Sec.2, Xinhai Rd., Daan District, Taipei City 106, Taiwan Fax: +886223626926 Mail: [email protected] National Taiwan Normal University Mandarin Training Center Tel: +886277345130 No.162 Hoping East Road , Sec.1 Taipei, Taiwan 106 Fax: +886223418431 Mail: [email protected] National Chiao Tung University Chinese Language Center Tel: +88635131231 No. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

Study in Taiwan - 7% Rich and Colorful Culture - 15% in Taiwan, Ancient Chinese Culture Is Uniquely Interwoven No.7 in the Fabric of Modern Society

Le ar ni ng pl us a d v e n t u r e Study in Foundation for International Cooperation in Higher Education of Taiwan (FICHET) Address: Room 202, No.5, Lane 199, Kinghua Street, Taipei City, Taiwan 10650, R.O.C. Taiwan Website: www.fichet.org.tw Tel: +886-2-23222280 Fax: +886-2-23222528 Ministry of Education, R.O.C. Address: No.5, ZhongShan South Road, Taipei, Taiwan 10051, R.O.C. Website: www.edu.tw www.studyintaiwan.org S t u d y n i T a i w a n FICHET: Your all – inclusive information source for studying in Taiwan FICHET (The Foundation for International Cooperation in Higher Education of Taiwan) is a Non-Profit Organization founded in 2005. It currently has 114 member universities. Tel: +886-2-23222280 Fax: +886-2-23222528 E-mail: [email protected] www.fichet.org.tw 加工:封面全面上霧P 局部上亮光 Why Taiwan? International Students’ Perspectives / Reasons Why Taiwan?1 Why Taiwan? Taiwan has an outstanding higher education system that provides opportunities for international students to study a wide variety of subjects, ranging from Chinese language and history to tropical agriculture and forestry, genetic engineering, business, semi-conductors and more. Chinese culture holds education and scholarship in high regard, and nowhere is this truer than in Taiwan. In Taiwan you will experience a vibrant, modern society rooted in one of world’s most venerable cultures, and populated by some of the most friendly and hospitable people on the planet. A great education can lead to a great future. What are you waiting for? Come to Taiwan and fulfill your dreams. -

American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter

CHAPTER FO U R American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter ★ he Buddha’s Birthday is celebrated for weeks on end in Los Angeles. TMore than three hundred Buddhist temples sit in this great city fac- ing the Pacific, and every weekend for most of the month of May the Buddha’s Birthday is observed somewhere, by some group—the Viet- namese at a community college in Orange County, the Japanese at their temples in central Los Angeles, the pan-Buddhist Sangha Council at a Korean temple in downtown L.A. My introduction to the Buddha’s Birthday observance was at Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights, just east of Los Angeles. It is said to be the largest Buddhist temple in the Western hemisphere, built by Chinese Buddhists hailing originally from Taiwan and advocating a progressive Humanistic Buddhism dedicated to the pos- itive transformation of the world. In an upscale Los Angeles suburb with its malls, doughnut shops, and gas stations, I was about to pull over and ask for directions when the road curved up a hill, and suddenly there it was— an opulent red and gold cluster of sloping tile rooftops like a radiant vision from another world, completely dominating the vista. The ornamental gateway read “International Buddhist Progress Society,” the name under which the temple is incorporated, and I gazed up in amazement. This was in 1991, and I had never seen anything like it in America. The entrance took me first into the Bodhisattva Hall of gilded images and rich lacquerwork, where five of the great bodhisattvas of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition receive the prayers of the faithful. -

Hsi Lai Temple Hacienda Heights Hello Again, Everybody! It’S a Little Different This Month – We Visit the Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights

8 APRIL 2016 City Employees Club of Los Angeles • Alive! Angel Gomez, Club Director of Sales 8 Angel’s Be Alive! Hsi Lai Temple Hacienda Heights Hello again, everybody! It’s a little different this month – we visit the Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights. If you hike the Hellman trail in Whittier, you can see the very top of the temple, which from there looks about the size of your hand. I always wanted to go see the inside of the temple but never got around to making the trip. So for this month, we did. I told my family, “Today, we are going to the temple in Hacienda Heights.” They all said “okay,” so off we went. That was easy! I should have done it a long time ago. History: The temple was built in 1988 and took more than 10 years to plan and construct. The founder of Hsi Lai Temple is Venerable Master Hsing Yun. This temple serves as a center for people interested in Buddhism and Chinese culture. “Hsi Lai” means “coming to the West.” Architecture found in the temple is loyal to the Ming and Ching dynasties. This includes buildings, gardens and statues. The Hsi Lai Temple covers 15 acres and 102,432 square feet. In the middle of the entire temple there is a cement area that is very open and spacious. The Hsi Lai Temple also has many information centers with Year of the Monkey decorations. detailed knowledge of Buddhism. We happened to go on the last day of the Chinese New Year celebra- tions. -

Humanistic Buddhism from Venerable Tai Xu to Grand Master Hsing Yun1

Humanistic Buddhism From Venerable Tai Xu to Grand Master Hsing Yun1 By Darui Long ABSTRACT The present essay aims at a historical. anal.ysis of Humanistic Buddhism that was preachedby Master Tai.Xu in the 1930s andthe great contribution Grand Master Hsing Yun has madeto the development of HumanisticBuddhism. What is Humanistic Buddhism? Why did Tai. Xu raise this issue of construcfing Humanistic Buddhism as his guiding principle in his reform of Chinese Buddhism? What did he do in his endeavors to realke his goal.? Did he succeed in bringing back the humanistic nature of Buddhism? What contributions has Grand Master Hsing Yun made to this cause? This essay makes attempts to answer these questions. It is divided into four parts. The first deals with the history of Humanistic Buddhism. It was Sakyamuni who first advanced Humanistic Buddhism. He lectured, meditated, propagated his way of life, and finally attained his Nirvana in the world. Hui-neng (638- 713 CE) emphasized that Buddhism is in theworld and thatit is not realiudapart from the world. The second chapter touches upon the historical. background of development and decline of Chinese Buddhism. It ilb4strates in detail how Buddhism declined in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasti.es. Corrupt officials vied with one another to confiscate the property of Buddhism in the late Qing and early years of the Republic of China. Even the lay Buddhist scholars made strong commentaries on the illness of Buddhism and Buddhists. Chapter 3 discusses the life and reform career of Venerable Tai. Xu (1889-1947). Being a revolutionary monk, Tai. -

Student Handbook

2019 Student Handbook TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 2 Foundation and History 2 Introducing Nan Tien Institute 2 SECTION 2. COURSES, ENTRY REQUIREMENTS AND FEES 3 Applied Buddhist Studies 3 Health and Social Wellbeing 4 Graduate Certificate in Humanistic Buddhism 5 Additional Information 5 Proficiency in English 5 Students in final year of undergraduate studies 5 Interview and references 5 SECTION 3. COURSE INFORMATION 6 Applied Buddhist Studies 6 Program Introduction 6 Graduate Certificate of Applied Buddhist Studies 6 Graduate Diploma of Applied Buddhist Studies 7 Master of Arts (Applied Buddhist Studies) 8 Course Advice 8 Subject Information 8 Health and Social Wellbeing Program 15 1. Program Introduction 15 2. Graduate Certificate in Health and Social Wellbeing 16 3. Graduate Diploma of Health and Social Wellbeing 16 4. Master of Arts (Health and Social Wellbeing) 16 5. Course Advice 17 6. Subject Information 17 Humanistic Buddhism Program 23 1. Program Introduction 23 2. Graduate Certificate in Humanistic Buddhism 23 3. Course Advice 23 4. Subject Information 24 SECTION 4. SERVICES 27 1. Accommodation 27 1.1 On campus accommodation 27 1.2 Off-campus accommodation 27 1.3 Tenancy information and advice 27 1.4 Finding off-campus accommodation 27 1.5 Temporary accommodation 28 2. Dining and Entertainment 28 2.1 Karma Cafe 28 2.2 Tea House of Nan Tien Temple 28 2.3 Dining Hall of Nan Tien Temple 29 2.4 Eating out and entertainment 29 3. Learning resources 29 3.1 MyLearning 29 3.2 Library 29 4. Student Services Office 30 NAN TIEN INSTITUTE – 2019 STUDENT GUIDE PAGE 1 SECTION 1. -

Host Institution

List of Participating Institutions for Program A and B 2020-1 (1st Cycle) Country/Territory Host Institution 1st Cycle 2nd Cycle Brunei 1 Universiti Brunei Darussalam 1 Universiti Brunei Darussalam 1 Brock University 2 Coast Mountain College 1 Coast Mountain College 3 Justice Institute of British Columbia 2 Justice Institute of British Columbia Canada 4 Memorial University of Newfoundland 3 Memorial University of Newfoundland 5 North Island College 4 North Island College 6 Okanagan College 5 Okanagan College 7 Yukon College 6 Yukon College 1 Universidad de los Andes 1 Universidad de los Andes Chile 2 Universidad Tecnica Federico Santa Maria 2 Universidad Tecnica Federico Santa Maria (Universidad Vina del Mar: 2nd only) 3 Universidad Vina del Mar China 1 Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University 1 Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University Indonesia 1 Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember 1 Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember 1 Aichi Prefectural University 1 Aichi Prefectural University 2 Hiroshima University 2 Hiroshima University 3 Kagawa University 3 Kagawa University 4 Musashi University 5 Nanzan University 6 Niigata University 4 Niigata University 7 Osaka Institute of Technology 5 Osaka Institute of Technology Japan 8 Otaru University of Commerce 6 Otaru University of Commerce 9 Shibaura Institute of technology 7 Shibaura Institute of technology 10 Shokei Gakuin University 8 Shokei Gakuin University 11 Showa Women's University 9 Showa Women's University 12 Toyo University 10 Toyo University 13 University of Fukui 11 University of Fukui 14 University of the Ryukyus 12 University of the Ryukyus (Hanyang University: 2nd only) 1 Hanyang University 1 Hongik University 2 Hongik University Korea (Kyungpook National University: 2nd only) 3 Kyungpook National University 2 Sejong University 4 Sejong University Kyrgyz 1 Kyrgyz State University I. -

Master's Letter to Dharma Protectors and Friends -- 2009

Master's Letter to Dharma Protectors and Friends -- 2009 Dear Dharma Protectors and Friends, Happy New Year to you all! May fruitful harvests be yielded through earnest cultivation. In time of the arrival of a new year, I cannot help but go over the past and look into the future,which is also my chance to share with everyone last year ’s propagation works we have done. On New Year ’s Day of 2008, Jian Zhen Library was completed after two and half years of construction, thereby allowing the opening ceremony of Jian Zhen Fo Guang Yuan Art Gallery and Yangzhou Forum to take place. Yangzhou is my homeland, and it is also an ancient cultural heritage. For the past thousand years, writers and poets left behind countless fine poems and pieces of works. During the great Qing dynasty, the Huizhou merchants and salt tradesmen gathered here and allowed the city to prosper. The rich history and civilization of this city has allowed it to become one of world ’s ten most bustling ancient capitals. With the completion of Jian Zhen Library and commencement of the Yangzhou Forum, the glory of Buddhist studies and culture in Yangzhou are bound to be revitalized. Under the leadership of curator Weng Zhenjin, the Yangzhou Forum was graced by the presence ofworld renowned speakers such as novelist Er Yue He, Qian Wenzhong, Ma Rui-fang, Yu Dan, Wang Bang-wei, Yan Chongnian, Kang Zhen, Cheng Shiyan, Charles HC Kao, Yu Kuangchung, Henry Lee, and Cui Yongyuan who delivered talks on Strange Tales of Liaozhai, Records of the Historian (Shi-ji), the Analects, Tang poems, Xuanzang ’s Journey to the West and so on. -

Ming-Hsiang Chen

MING-HSIANG CHEN School of Hospitality Business Management Carson College of Business Washington State University Tel.: +1-509-335-2317 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. Economics, Kansas State University (KSU), 5/2001 MBA KSU, 5/1997. Concentrations: Finance, Production and Operations Management ACADEMIC POSITIONS Associate Professor, School of Hospitality Business Management (SHBM) Carson College of Business (CCB), Washington State University (WSU), 8/2015 Distinguished Visiting Research Chair Professor, College of Business and Tourism Management, Yunnan University, 2015- 2018 Distinguished Visiting Professor, College of Geography and Tourism, Qufu Normal University, 2015-2020 Research Advisor, Center for Recreation and Economic Research, Beijing International Studies University, 2015- 2018 Professor, Department of Finance, National Chung Cheng University (CCU), 8/2010- 7/2015 Associate Professor, Department of Finance, CCU, 8/2005- 7/2010 Assistant Professor, Department of Finance, CCU, 8/2001- 7/2005 Teaching Assistant, Department of Economics, KSU, 1/1999- 5/2001 Instructor, Department of Management, KSU, 8/1997- 5/1998 Teaching/Research Assistant, Department of Management, KSU, 8/1996- 5/1997 TEACHING INTERESTS Investments, Financial Markets and Institutions, Money and Banking, Macroeconomics Financial Management, Revenue Management, Asset Management Hospitality Operational Analysis, Tourism Market Analysis, Tourism Economics 1 2/2016 Updated COURSES TAUGHT School of Hospitality Business Management, WSU Undergraduate: