Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

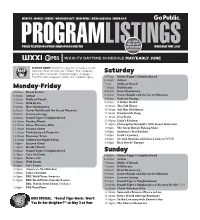

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

2/1/75 - Mardi Gras Ball” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 2, folder “2/1/75 - Mardi Gras Ball” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. A MARDI GRAS HISTORY Back in the early 1930's, United States Senator Joseph KING'S CAKE Eugene Ransdell invited a few fellow Louisianians to his Washington home for a get together. Out of this meeting grew 2 pounds cake flour 6 or roore eggs the Louisiana State Society and, in turn, the first Mardi Gras l cup sugar 1/4 cup warm mi lk Ball. The king of the first ball was the Honorable F. Edward 1/2 oz. yeast l/2oz. salt Hebert. The late Hale Boggs was king of the second ball . l pound butter Candies to decorate The Washington Mardi Gras Ball, of course, has its origins in the Nardi Gras celebration in New Orleans, which in turn dates Put I 1/2 pounds flour in mixing bowl. -

National Press Club Luncheon with Newt Gingrich, Former Speaker of the House of Representatives

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH NEWT GINGRICH, FORMER SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES MODERATOR: JERRY ZREMSKI LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: TUESDAY, AUGUST 7, 2007 (C) COPYRIGHT 2005, FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC., 1000 VERMONT AVE. NW; 5TH FLOOR; WASHINGTON, DC - 20005, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. IS A PRIVATE FIRM AND IS NOT AFFILIATED WITH THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT IS CLAIMED AS TO ANY PART OF THE ORIGINAL WORK PREPARED BY A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT OFFICER OR EMPLOYEE AS PART OF THAT PERSON'S OFFICIAL DUTIES. FOR INFORMATION ON SUBSCRIBING TO FNS, PLEASE CALL JACK GRAEME AT 202-347-1400. ------------------------- MR. ZREMSKI: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Jerry Zremski, and I'm the Washington bureau chief for the Buffalo News and president of the Press Club. I'd like to welcome our club members and their guests who are with this today, as well as those of you who are watching on C-SPAN. We're looking forward to today's speech, and afterwards, I'll ask as many questions as time permits. Please hold your applause during the speech so that we have as much time for questions as possible. For our broadcast audience, I'd like to explain that if you hear applause during the speech, it may be from the guests and members of the general public who attend our luncheons and not necessarily from the working press. -

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the Power of Childhood Meets the Power of Research

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the power of childhood meets the power of research 2016 ANNUAL REPORT WHERE BREAKTHROUGHS HAPPEN The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the world’s premier biomedical research institution—and the breakthroughs that happen here are the first steps toward eradicating diseases, easing pain, and making better lives possible. None Inn residents of these medical advances would be participated possible without the people who drive them: children, families and caregivers, in 283 clinicians and staff—the community The CLINICAL Children’s Inn brings together. The Inn TRIALS provides relief, support, and strength to at the NIH these pioneers whose participation in in FY16 medical trials at the NIH can change the story for children around the world. Inn residents are a part of pediatric protocols in 15 of the 27 INSTITUTES and CENTERS at the NIH On the cover: Inn resident Reem, age 7 from Egypt, with her NIH physician, Dr. Neal Young. She is being treated for aplastic anemia at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. As partners in discovery and care, OUR VISION we strive for the day when no family endures the heartbreak of a seriously ill child. Letter from the Chair of the Board and Chief Executive Officer The Inn’s Board of Directors had an eventful We are so grateful to you: our donors, volunteers, year. We have worked diligently to restructure and friends, who help The Children’s Inn make a and prepare The Inn for the future, and recently profound impact on the lives of the NIH’s young- welcomed some talented new members to our est patients. -

Bolton's Budget Talks Collapse

J u N anrbpBtpr Hrralb Newsstand Price: 35 Cents Weekend Edition, Saturday, June 23,1990 Manchester — A City of Village Charm Bolton’s budget talks collapse TNT, CASE fail to come to terms.. .page 4 O \ 5 - n II ' 4 ^ n ^ H 5 Iran death S i z m toll tops O "D 36,1 Q -n m rn w State group S o sends aid..page 2 s > > I - 3 3 CO 3 3 > > H ■ u ^ / Gas rate hike requested; 9.8 percent > 1 4 MONTH*MOK Coventry will be Judy Hartling/Manchealsr Herald BUBBLING AND STRUGGLING — Gynamarie Dionne, age 4, tries for a drink from the affected.. .page 8 fountain at Manchester’s Center F*ark. Her father, Scott, is in the background. Moments later, he gave her a lift. ,...___ 1 9 9 0 J u p ' ^ ‘Robin HUD .■ '• r ■4 given stiff (y* ■ • i r r ■ prison term 1 . I* By Alex Dominguez The Associated Press BALTIMORE “Robin HUD,” the former real estate agent who claimed she stole about $6 million from HUD to help the poor, was sentenced Friday to the maximum prison term of nearly four years. t The Associated Press U.S. District Judge Herbert Murray issued the 46- month sentence at the request of the agent, Marilyn Har rell, who federal officials said stole more from the government than any individual. “I will ask you for the maximum term because I DEATH AND SURVIVAL — A father, above, deserve it,” Harrell told the judge. “I have never said what I did was right. -

Assignment Russia’ Review: Murrow’S Man in Moscow Khrushchev Called the 6-Foot-3 Marvin Kalb ‘Peter the Great’—And in Paris Shared Croissants with the CBS Reporter

DOW JONES, A NEWS CORP COMPANY About WSJ DJIA 32627.97 0.71% ▼ S&P 500 3913.10 0.06% ▼ Nasdaq 13215.24 0.76% ▲ U.S. 10 Yr 0/32 Yield 1.726% ▼ Crude Oil 61.44 0.03% ▲ Euro 1.1906 0.09% ▼ The Wall Street Journal John Kosner GET MARKETS ALERTS English Edition Print Edition Video Podcasts Latest Headlines Home World U.S. Politics Economy Business Tech Markets Opinion Life & Arts Real Estate WSJ. Magazine Search BEST OF GUIDE TO THE OSCAR NOMINATIONS WEEKEND READS BEST BOOKS OF FEBRUARY FRESH EYES ON THE FRICK COLLECTION LATEST MOVIE REVIEWS BEST SPY NOVELS Arts & Review BEST BOOKS OF 2020 BOOKS | BOOKSHELF SHARE ‘Assignment Russia’ Review: Murrow’s Man in Moscow Khrushchev called the 6-foot-3 Marvin Kalb ‘Peter the Great’—and in Paris shared croissants with the CBS reporter. By Edward Kosner March 18, 2021 7:04 pm ET SAVE PRINT TEXT Listen to this article 6 minutes Roger Mudd ascended to Network News Heaven at 93 last week. There he was reunited with Walter Cronkite, John Chancellor, Douglas Edwards, Howard K. Smith, Edward R. Murrow and other luminaries. Still with us are old hands Dan Rather, Diane Sawyer, Bernard Shaw, and the Kalb brothers, Marvin and Bernard—living witnesses to the days when TV news was more serious business and less partisan gasbaggery. Now Marvin Kalb, himself 90 but acute as ever, has written a memoir of his early career, especially his years as Moscow correspondent for CBS News in the direst period of the Cold War. -

After the Financial Crisis: Ongoing Challenges Facing Delphi Retirees

AFTER THE FINANCIAL CRISIS: ONGOING CHALLENGES FACING DELPHI RETIREES FIELD HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 13, 2010 Printed for the use of the Committee on Financial Services Serial No. 111–143 ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 61–847 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 18:29 Nov 12, 2010 Jkt 061847 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 K:\DOCS\61847.TXT TERRIE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts, Chairman PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama MAXINE WATERS, California MICHAEL N. CASTLE, Delaware CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York PETER T. KING, New York LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois EDWARD R. ROYCE, California NYDIA M. VELA´ ZQUEZ, New York FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina RON PAUL, Texas GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois BRAD SHERMAN, California WALTER B. JONES, JR., North Carolina GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York JUDY BIGGERT, Illinois DENNIS MOORE, Kansas GARY G. MILLER, California MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts SHELLEY MOORE CAPITO, West Virginia RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEB HENSARLING, Texas WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri SCOTT GARRETT, New Jersey CAROLYN MCCARTHY, New York J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina JOE BACA, California JIM GERLACH, Pennsylvania STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts RANDY NEUGEBAUER, Texas BRAD MILLER, North Carolina TOM PRICE, Georgia DAVID SCOTT, Georgia PATRICK T. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

Cokie Roberts Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript

Cokie Roberts Congressional Correspondent and Daughter of Representatives Hale and Lindy Boggs of Louisiana Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript May 25, 2017 Office of the Historian U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. “And so she [Lindy Boggs] was on the Banking Committee. They were marking up or writing a piece of legislation to end discrimination in lending. And the language said, ‘on the basis of race, national origin, or creed’—something like that. And as she told the story, she went into the back room and wrote in, in longhand, ‘or sex or marital status,’ and Xeroxed it, and brought it back into the committee, and said, ‘I’m sure this was just an omission on the part of my colleagues who are so distinguished.’ That’s how we got equal credit, ladies.” Cokie Roberts May 25, 2017 Table of Contents Interview Abstract i Interviewee Biography i Editing Practices ii Citation Information iii Interviewer Biographies iii Interview 1 Notes 29 Abstract On May 25, 2017, the Office of the House Historian participated in a live oral history event, “An Afternoon with Cokie Roberts,” hosted by the Capitol Visitor Center. Much of the interview focused on Cokie Roberts’ reflections of her mother Lindy Boggs whose half-century association with the House spanned her time as the spouse of Representative Hale Boggs and later as a Member of Congress for 18 years. Roberts discusses the successful partnership of her parents during Hale Boggs’ 14 terms in the House. She describes the significant role Lindy Boggs played in the daily operation of her husband’s congressional office as a political confidante and expert campaigner—a function that continued to grow and led to her overseeing much of the Louisiana district work when Hale Boggs won a spot in the Democratic House Leadership. -

CQ Committee Guide

SPECIAL REPORT Committee Guide Complete House and senate RosteRs: 113tH CongRess, seCond session DOUGLAS GRAHAM/CQ ROLL CALL THE PEOPLE'S BUSINESS: The House Energy and Commerce Committee, in its Rayburn House Office Building home, marks up bills on Medicare and the Federal Communications Commission in July 2013. www.cq.com | MARCH 24, 2014 | CQ WEEKLY 431 09comms-cover layout.indd 431 3/21/2014 5:12:22 PM SPECIAL REPORT Senate Leadership: 113th Congress, Second Session President of the Senate: Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. President Pro Tempore: Patrick J. Leahy, D-Vt. DEMOCRATIC LEADERS Majority Leader . Harry Reid, Nev. Steering and Outreach Majority Whip . Richard J. Durbin, Ill. Committee Chairman . Mark Begich, Alaska Conference Vice Chairman . Charles E. Schumer, N.Y. Chief Deputy Whip . Barbara Boxer, Calif. Policy Committee Chairman . Charles E. Schumer, N.Y. Democratic Senatorial Campaign Conference Secretary . Patty Murray, Wash. Committee Chairman . Michael Bennet, Colo. REPUBLICAN LEADERS Minority Leader . Mitch McConnell, Ky. Policy Committee Chairman . John Barrasso, Wyo. Minority Whip . John Cornyn, Texas Chief Deputy Whip . Michael D. Crapo, Idaho Conference Chairman . John Thune, S.D. National Republican Senatorial Conference Vice Chairman . Roy Blunt, Mo. Committee Chairman . Jerry Moran, Kan. House Leadership: 113th Congress, Second Session Speaker of the House: John A. Boehner, R-Ohio REPUBLICAN LEADERS Majority Leader . Eric Cantor, Va. Policy Committee Chairman . James Lankford, Okla. Majority Whip . Kevin McCarthy, Calif. Chief Deputy Whip . Peter Roskam, Ill. Conference Chairwoman . .Cathy McMorris Rodgers, Wash. National Republican Congressional Conference Vice Chairwoman . Lynn Jenkins, Kan. Committee Chairman . .Greg Walden, Ore. Conference Secretary . Virginia Foxx, N.C.