The Life of Steve Jobs: a Psychobiographical Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEYOND WORDS Incorporating Collage, Cultural Criticism, Poetry and Video, Adam Pendleton’S Work Defies Categorization

the exchange aRt TALK BEYOND WORDS Incorporating collage, cultural criticism, poetry and video, Adam Pendleton’s work defies categorization. That’s only part of what makes it so appealing to collectors and museums alike. BY TED LOOS PHOTOGRAPHY BY CARLOS CHAVARRÍA HEN AN ARTIST captures a cultural he writes. Pendleton doesn’t think he invented the Being gay and black gave him a useful outsider’s moment just so, it’s like a lightning conversation that he’s a part of. “It is a continuum,” he perspective. “When you’re sort of off to the side, you bolt—there’s a crackle in the air, a blind- says, “but it doesn’t only move forward; it moves back- supply yourself with something that long term is ing flash, and the clouds part. At just 34, wards and sideways, too.” ultimately more productive,” he says. (Pendleton is WBrooklyn-based artist Adam Pendleton has proved Though he works in many media, much of his now married to a food entrepreneur, and they live in himself capable of generating such phenomena. visual work starts as collage, and he has a canny eye Brooklyn’s Fort Greene.) Over the past decade, Pendleton’s conceptual take for juxtapositions that recalls one of his idols, Jasper In 2002, he completed a two-year independent art- on race in America has drawn attention and stirred Johns. “Already in his incredibly youthful career, he ist’s study program in Pietrasanta, Italy, but he doesn’t discussion across the country. Last year, he had solo has managed to land on a graphic language that is have a bachelor’s degree or an M.F.A. -

Connecting the Dots

MAIN STAGE | Festivals CONNECTING THE DOTS Six years after his death at the age of 56, Steve Jobs has achieved an almost mythical status as the cultural icon and technological innovator behind Apple. A new opera, The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, receives its much-anticipated world premiere at Santa Fe Opera in July. Thomas May meets the creative team who have incorporated a few innovations of their own to tell the story of a world- changing legend. e’s everywhere, indispensable. Every time we communicate on a smart phone, laptop or tablet, Steve Jobs is with us. It’s difficult to think of a figure in recent history who pervades our culture more thoroughly. His Hlarger-than-life presence is mirrored by the intensely polarised reactions of fans and foes who deify or demonise him. What could be more suitable as a subject for the opera stage? Yet it was not only the revolution inspired by the tech genius but his all-too-human struggles that convinced the creators of The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs that here was a story ripe for operatic treatment. ‘What I was drawn to in his story is the role Steve Jobs played in transforming human communication,’ Making sense of the contradictions: Edward Parks creates ⌂ DARIO ACOSTA says Mason Bates from his home in the Bay Area of San Francisco, the role of Steve Jobs in Santa Fe’s landmark new commission www.operanow.co.uk JUNE 2017 Opera Now 31 ON0617_031-034_F_SantaFe1505OM.indd 31 16/05/2017 15:38 MAIN STAGE | Festivals KATE WARREN KATE Composer Mason Bates has incorporated eerily beautiful electronic sounds into his score Mark Campbell, librettist: ‘I tend to like a style that is expansive and not cramped’ ⌂ where Jobs himself grew up. -

The (R)Evolution of Steve Jobs Makes West Coast Premiere at Seattle Opera

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Jan. 23, 2019 Contact: Gabrielle Kazuko Nomura Gainor, 206.676.5559, [email protected] Press images: https://seattleopera.smugmug.com/1819/Stevejobs/ Password: “press” (case sensitive) The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs makes West Coast premiere at Seattle Opera Grammy-nominated music unites electronic and classical genres Feb. 23–March 9, 2019 McCaw Hall SEATTLE — Do you remember what life was like before the iPhone? Steve Jobs, the man who created that game-changing device in your pocket, will soon have his story play out at McCaw Hall. This February, Seattle Opera presents the West Coast premiere of The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, a smash hit with music nominated for multiple Grammy Awards. “For better or worse, humanity will never be the same because of Jobs’ products and the cultural transformation that they helped usher in,” said Seattle Opera General Director Aidan Lang. “As we explore this complicated man onstage, we also hope to spur dialogue about the impact of technology in our lives, and examine how the tech industry has impacted our community here in the Pacific Northwest.” Seattle Opera’s production begins with a crucial point in Jobs’ life: Faced with mortality, the CEO revisits 18 of his most important memories in search of a perfect moment to take with him. He examines the people and experiences that shaped him the most: his father’s mentorship, his devotion to Buddhism, his relationships, his professional rise and fall, and finally his marriage to Laurene Jobs, who showed him the power of human connection. Starring in the role of the turtleneck-clad mogul is acclaimed baritone John Moore who wowed Seattleites as Figaro in The Barber of Seville and as Papageno in The Magic Flute. -

A Psychobiographical Study of Steven Paul Jobs

A PSYCHOBIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF STEVEN PAUL JOBS N. MOORE 2014 A PSYCHOBIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF STEVEN PAUL JOBS By Noëlle Moore Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology to be awarded at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University March 2014 Supervisor: Professor Greg Howcroft i DECLARATION I, Noëlle Moore (205003435), hereby declare that the treatise for Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification. Noelle Moore Official use: In accordance with Rule G4.6.3, 4.6.3 A treatise/dissertation/thesis must be accompanied by a written declaration on the part of the candidate to the effect that it is his/her own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. However, material from publications by the candidate may be embodied in a treatise/dissertation/thesis. ii Here‘s to the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the round pegs in the square holes...the ones who see things differently – they‘re not fond of rules...You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them, but one thing you can‘t do is ignore them because they change things...they change things...they push the human race forward, and while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius, because the ones who are crazy enough to think that they can change the world, are the ones who do (Steven Paul Jobs, 1955 – 2011). -

Apple's Mac Team Gathers for Insanely Great Twiggy Mac Reunion

Apple's Mac team gathers for insanely great Twiggy Mac reunion SILICON BEAT By Mike Cassidy Mercury News Columnist ([email protected] / 408-920-5536 / Twitter.com/mikecassidy) POSTED: 09/12/2013 11:57:40 AM PDT MOUNTAIN VIEW -- In Silicon Valley, it's not a question of "What have you done for me lately?" -- the question is, "So, what are you going to do for me next?" And so, you have to wonder what it's like to be best known for something you did 30 years ago. Randy Wigginton, one of the freewheeling pirates who worked under Steve Jobs on Apple's (AAPL) dent-in-the-world, 1984 Macintosh, has an easy answer. "It's awesome," says Wigginton, who led the effort on the MacWrite word processor. "People don't get to change the world very often. How much luckier can a guy be? I've had a very blessed life." The blessings were very much on Wigginton's mind the other day as he and a long list of early Apple employees got together to check out the resurrection of a rare machine known as the Twiggy Mac. The prototype was a key chapter in the development of the original Mac, which of course was a key chapter in the development of the personal computer and by extension the personal music player, the smartphone, the smart tablet and a nearly ubiquitous digital lifestyle that has turned the world on its head. Some of the key players in that story, first immortalized in Steven Levy's "Insanely Great" and again in Walter Isaacson's "Steve Jobs" and most recently, docudrama fashion, in the movie "Jobs," gathered at the Computer History Museum to get a look at the Mac and at old friends who'd done so much together. -

A Film Really About Heroines

“Steve Jobs”: A Film Really About Heroines Mark P. Barry February 1, 2016 When Steve Jobs died in 2011, his authorized biography was rushed to press, quickly followed by the low-budget, independent film, “Jobs.” Fans of the Apple CEO had to wait until last October for the full Hollywood production, “Steve Jobs,” featuring an A-list cast and team, to reach the big screen. Audiences were disappointed in the film because it bombed at the box office. Expectations surely were for a depiction of Jobs’ stellar technology and business achievements. But the truth is: this movie is more about its heroines than its hero. For her performance in “Steve Jobs,” Kate Winslet won the 2016 Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress and is nominated for an Oscar this year as well. She plays Joanna Hoffman, long-time marketing chief at Apple and “right-hand woman” to its co-founder. Known as the one person who could stand up to the difficult and temperamental Jobs, in the film Hoffman calls herself his “work wife.” Winslet, as Joanna, is the moral center of the movie. Very loosely based on the Walter Isaacson official biography – a book Apple Mark P. Barry and Jobs’ family were not happy with – “Steve Jobs” is written by Aaron Sorkin, who won the 2011 Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for “The Social Network” and this year’s Golden Globe for Best Screenplay for “Steve Jobs.” “Steve Jobs” was lucky to get made. It was originally produced by Sony Pictures, but after North Korea hacked its computers in late 2014, divulging embarrassing executive emails, Universal Pictures acquired the film. -

From Generosity to Justice, a New Gospel of Wealth

FROM GENEROSITY TO JUSTICE TO GENEROSITY FROM Pr a ise for From Generosity to Justice ndrew Carnegie wrote “The Gospel of “This will become a defining manifesto of our era.” A Wealth” in 1889, during the height of the —Walter Isaacson Gilded Age, when 4,000 American families controlled almost as much wealth as the rest of “Walker bravely tackles the subject of inequality with one pressing FROM the country combined. His essay laid the foun- Darren Walker is president of the Ford question in mind: What can philanthropy do about it?” dation for modern philanthropy. Foundation, a $13 billion international social justice —Ken Chenault Today, we find ourselves in a new Gilded philanthropy. He is co-founder and chair of the U.S. Age—defined by levels of inequality that sur- Impact Investing Alliance and the Presidents’ Council “A recalibration and reimagination of the philanthropic model crafted pass those of Carnegie’s time. The widening on Disability Inclusion in Philanthropy. by the Carnegie and Rockefeller families over a century ago. This new GENEROSITY chasm between the advantaged and the disad- Before joining Ford, Darren was vice president at the gospel must be heard all over the world!” vantaged demands our immediate attention. Rockefeller Foundation, overseeing global and domestic —David Rockefeller, Jr. Now is the time for a new Gospel of Wealth. programs. In the 1990s, he was COO of the Abyssinian In From Generosity to Justice: A New Gos- Development Corporation, Harlem’s largest community “Orchestrating a dynamic chorus of vital voices and vibrant vision, pel of Wealth, Darren Walker, president of the development organization. -

Private Tribute to Steve Jobs Planned for Sunday 15 October 2011

Private tribute to Steve Jobs planned for Sunday 15 October 2011 Internet royalty have been invited to a memorial to be held for Steve Jobs on Sunday at Stanford University in Silicon Valley. Apple said the event was private and that even press would not be permitted unless they were on the guest list. Responses to invitations were reportedly directed to Emerson Collective, a philanthropy founded by the Apple co-founder's wife, Laurene Powell Jobs. Jobs died in on October 5 at the age of 56 after a years-long battle with cancer. He was buried in a private ceremony at a non-denominational cemetery three days later. Jobs was also to be honored during an October 19 memorial for Apple employees at the company's headquarters in Cupertino, California. "We are planning a celebration of Steve's extraordinary life for Apple employees that will take place soon," Apple chief executive Tim Cook said in a statement released the day Jobs died. Apple has not indicated plans for a public memorial for Jobs, but people have paid tribute to him with flowers, candles, messages and more outside his home, the company headquarters and Apple retail stores around the world. (c) 2011 AFP APA citation: Private tribute to Steve Jobs planned for Sunday (2011, October 15) retrieved 24 September 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2011-10-private-tribute-steve-jobs-sunday.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. -

The Remarkable Odyssey of Bill Fernandez Techrepublic

10/22/2015 Apple's first employee: The remarkable odyssey of Bill Fernandez TechRepublic Apple's first employee: The remarkable odyssey of Bill Fernandez By Jason Hiner[1] Perhaps best known as the guy who introduced Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, Bill Fernandez speaks out on Apple's founding magic, how love built the first Mac, and the interface of the future. The Apple II got there first. It was the Wright Flyer I of personal computers. When the Wright brothers made their historic first flight in 1903, lots of other inventors were trying to fling their own shoddy little planes into the air. And in 1977, when Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs unveiled the Apple II, there were a zillion other nerds working on building a personal computer. But Woz beat them to it, and Jobs knew how to sell it. The Apple II was the product that turned Apple into Apple. It was the iPhone of its era, the product that redefined every machine like it that came afterward. Its real magic was Wozniak's minimalism. He integrated many technologies and components that no one else had put together in the same device, and he did it with as few parts as possible. It was, as Wozniak wrote in his autobiography, "the first low-cost computer which, out of the box, you didn't have to be a geek to use." But as genius as Wozniak was, the Apple II almost didn't make it out of his brain and into a product that the rest of the world could use. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sustainable Gardens of the Mind: Beat Ecopoetry and Prose in Stewart Brand's Whole Earth Publications Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5x63g2bt Author Lewak, Susan Elizabeth Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Sustainable Gardens of the Mind: Beat Ecopoetry and Prose in Stewart Brand's Whole Earth Publications A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy in English by Susan Elizabeth Lewak 2014 © Copyright by Susan Elizabeth Lewak 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Sustainable Gardens of the Mind: Beat Ecopoetry and Prose in Stewart Brand's Whole Earth Publications By Susan Elizabeth Lewak Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Michael A. North, Chair Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth publications (The Whole Earth Catalog, The Supplement to the Whole Earth Catalog, CoEvolution Quarterly, The Whole Earth Review, and Whole Earth) were well known not only for showcasing alternative approaches to technology, the environment, and Eastern mysticism, but also for their tendency to juxtapose radical and seemingly contradictory subjects in an “open form” format. They have also been the focus of notable works of scholarship in the social sciences. Areas of exploration include their relationship to the development of the personal computer, the environmental movement and alternative technology, the alternative West Coast publishing industry, Space Colonies, and Nanotechnology. What is perhaps less well known is Brand’s interest in the Beat poetry of Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gregory Corso, Robert Creeley, David Meltzer, and Peter Orlovsky beginning with CoEvolution Quarterly in 1974. -

Laurene-Powell-Jobs

Laurene Powell Jobs is investing in media, education, sports and more. What does she want? Laurene Powell Jobs — like the inventors and disrupters who were all around her — was thinking big. It was 2004, and she was an East Coast transplant — sprung from a cage in West Milford, N.J., as her musical idol Bruce Springsteen might put it — acclimating to the audacious sense of possibility suffusing the laboratories, garages and office parks of Silicon Valley. She could often be found at a desk in a rented office in Palo Alto, Calif., working a phone and an Apple computer. There, her own creation was beginning to take shape. It would involve philanthropy … technology … social change — she was charting the destination as she made the journey. She eventually named the project Emerson Collective after Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of her favorite writers. In time it would become perhaps the most influential product of Silicon Valley that you’ve never heard of. Yet at first, growth was slow. The work took a back seat to raising her three children and managing the care of her husband, Steve Jobs, as he battled the cancer that killed him in 2011 at age 56, followed by a period of working through family grief. She inherited his fortune, now worth something like $20 billion, and became the sixth-richest woman on the planet. By 2014, Emerson Collective was up to 10 employees. “For the first few years I worked here, there would be people who would say, ‘Who?’ ” says the eighth hire, Anne Marie Burgoyne, director of grants. -

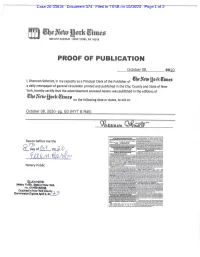

Case 20-33918 Document 374 Filed in TXSB on 10/08/20 Page 1 of 2

Case 20-33918 Document 374 Filed in TXSB on 10/08/20 Page 1 of 2 Case 20-33918 Document 374 Filed in TXSB on 10/08/20 Page 2 of 2 C M Y K Nxxx,2020-10-08,B,003,Bs-BW,E1 THE NEW YORK TIMES BUSINESS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 8, 2020 N B3 ENERGY | MEDIA | FINANCE Citing Safety, Agencies Concede Poor Planning in California Blackouts By IVAN PENN Outlet Pulls A report by California energy offi- cials on Tuesday placed blame for rolling blackouts that left millions White House without power in August on the impact of climate change and out- dated policies and practices that Reporter failed to adequately take into ac- By KATIE ROBERTSON count hotter weather. In the 121-page preliminary re- BuzzFeed News has pulled a polit- port to Gov. Gavin Newsom, the ical correspondent from the White state’s three central energy orga- House press pool, citing concerns nizations attributed the blackouts that the area has become a co- — the first in two decades — to a ronavirus hot zone after President heat wave that increased demand Trump, many of his top aides — in- for electricity while reducing the cluding the press secretary supply of power. Poor planning Kayleigh McEnany — and several compounded those problems, ac- journalists have tested positive cording to the report, which was for the virus. produced by the California Ener- A BuzzFeed News spokesman, gy Commission, the California Matt Mittenthal, confirmed that Public Utilities Commission and the company on Tuesday had the California Independent Sys- withdrawn the correspondent, tem Operator.