Anglo-Saxon Hampshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oakley Farmhouse

Oakley Farmhouse Oakley Lane • Mottisfont • Hampshire • SO51 0DR Oakley Farmhouse Oakley Lane • Mottisfont • Hampshire • SO51 0DR A Georgian farmhouse with stunning riverside gardens on the famous River Test Accommodation Reception hall • Drawing room • Dining room • Family room • Kitchen/breakfast room • Cellar • Utility room Rear hall/boot room • Master bedroom and bathroom • 5 further bedrooms • 2 further bathrooms Excellent outbuildings including large brick built barn with slate roof and adjoining machinery sheds • Separate 4-bay barn built of brick with slate roof Hard tennis court • Croquet lawn • Formal and informal gardens • Wild fl ower meadows • Approximately 270 metres frontage to River Test Leasehold 99 years new National Trust lease In all about 5.56 acres Romsey 4 miles • Stockbridge 6.5 miles • Winchester 13 miles (Waterloo 57 minutes) • Salisbury 16 miles (all mileages are approximate) SaviIls Winchester 1 Jewry Street, Winchester, SO23 8RZ [email protected] 01962 841 842 Situation There is good access to the A303, A34, M3 and M27 and fly-fishing, FM Halford. His thatched fishing hut, a listed building Mottisfont is a quiet rural Test valley village famous for its Abbey there are main line railway stations in Salisbury, Winchester and in its own right, lies upstream of the house, directly opposite the and its Norman church. Mottisfont Abbey, founded in the 12th Grateley with services to London Waterloo. Sporting facilities in Farmhouse meadow. century and now owned by the National Trust, is home to the the area are first class, including chalk stream fishing on the River celebrated National Rose collection. Oakley Farmhouse is a Test and its tributaries, and the River Itchen to the east. -

Why Grateley? Reflections on Anglo-Saxon Kingship in a Hampshire Landscape

WHY GRATELEY? REFLECTIONS ON ANGLO-SAXON KINGSHIP IN A HAMPSHIRE LANDSCAPE RYAN LAVELLE Faculty of Social Sciences (History), University of Winchester, Winchester, Hants. SO22 4NR, UK; +44 (0)1962 827137 [email protected]; http://www.winchester.ac.uk/?page=7557 PLEASE NOTE: The definitive version of this paper can be found in Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society 60 (2005), 154-69. This version of the paper has been paginated for convenience only; citation of this paper should use the definitive (printed) version. This electronic version is has been made available by kind permission of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society http://www.fieldclub.hants.org.uk/ ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the context of the promulgation of the first ‘national’ lawcode of King Athelstan at Grateley (c.925x30; probably 926x7). A localised context allows a consideration of the arrangements of the royal resources which supplied the Anglo-Saxon ‘national’ assembly, the witangemot. In so doing, the paper looks at royal estate organisation in Andover hundred in north- western Hampshire, making a case for the significance of Andover itself. Finally, the role of the landscape in the political ritual of lawmaking is discussed. INTRODUCTION article may not concur with Wood’s tentative designation of Andover and Grateley as separate This paper addresses the exercise of Anglo- territories, each focused on hillforts, it is intended Saxon kingship, manifested in land organisation to build on his proposition, addressing the in the hundred of Andover. For the most part, the question of the royal territory—arguably an early area under discussion is an undulating chalk royal territory—in the expression of authority on downland landscape to which some distinctive a ‘national’ scale. -

Hampshire and the Company of White Paper Makers

HAMPSHIRE AND THE COMPANY OF WHITE PAPER MAKERS By J. H. THOMAS, B.A. HAMPSHIRE has long been associated with the manufacturing of writing materials, parchment being made at Andover, in the north of the county, as early as the 13th century.1 Not until some four centuries later, however, did Hampshire embark upon the making of paper, with Sir Thomas Neale (1565-1620/1) financing the construction of the one-vat mill at Warnford, in the Meon Valley, about the year 1618. As far as natural requirements were concerned, Hampshire was well-endowed for the making of paper. Clear, swift chalk-based streams ensured a steady supply of water, for use both as motive power and in the actual process of production. Rags, old ropes and sails provided the raw materials for conversion into paper, while labour was to be found in the predominantly rural population. The amount of capital required varied depend ing on the size of the mill concerned, and whether it was a conversion of existing plant, as happened at Bramshott during the years 1640-90, or whether the mill was an entirely new construction as was the case at Warnford and, so far as is known, the case with Frog Mill at nearby Curdridge. Nevertheless Hampshire, like other paper-making counties, was subject to certain restraining factors. A very harsh winter, freezing the water supply, would lead to a cut-back in production. A shortage of materials and the occurrence of Holy days would have a similar result, so that in 1700 contemporaries reckoned on an average working year of roughly 200 days.2 Serious outbreaks of plague would also hamper production, the paper-makers of Suffolk falling on hard times for this reason in 1638.3 Though Hampshire had only one paper mill in 1620, she possessed a total of ten by 1700,4 and with one exception all were engaged in the making of brown paper. -

Planning Services

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 47 Week Ending: 23rd November 2018 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 18/03025/TREEN Fell Fir Tree encroaching on Pollyanna, Little Ann Road, Mr Patrick Roberts Mr Rory Gogan YES 19.11.2018 Cherry tree; T1 Ash and T2 Little Ann, Andover Hampshire 21.12.2018 ABBOTTS ANN Ash both showing signs of SP11 7SN desease and some dieback (see full description on form) 18/03018/FULLN Change of use from Telford Gate, Unit 1 , Mr Ricky Sumner, RSV Mr Luke Benjamin 19.11.2018 factory/warehouse to general Hopkinson Way, Portway Services 12.12.2018 ANDOVER TOWN industrial to include vehicle Business Park, Andover SP10 (HARROWAY) repairs and servicing and 3SF MOT testing 18/03067/CLEN -

Unclassified Fourteenth- Century Purbeck Marble Incised Slabs

Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No. 60 EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS This book is published with the generous assistance of The Francis Coales Charitable Trust. EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS Sally Badham and Malcolm Norris The Society of Antiquaries of London First published 1999 Dedication by In memory of Frank Allen Greenhill MA, FSA, The Society of Antiquaries of London FSA (Scot) (1896 to 1983) Burlington House Piccadilly In carrying out our study of the incised slabs and London WlV OHS related brasses from the thirteenth- and fourteenth- century London marblers' workshops, we have © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1999 drawn very heavily on Greenhill's records. His rubbings of incised slabs, mostly made in the 1920s All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, and 1930s, often show them better preserved than no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval they are now and his unpublished notes provide system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, much invaluable background information. Without transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, access to his material, our study would have been less without the prior permission of the copyright owner. complete. For this reason, we wish to dedicate this volume to Greenhill's memory. ISBN 0 854312722 ISSN 0953-7163 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the -

Flood Risks in the Littleton and Harestock Area

Flood Risks in the Littleton & Harestock Area (Ver 1.0 dated 9 Jan 2020) FLOOD RISKS IN THE LITTLETON AND HARESTOCK AREA Purpose of presentation This purpose of this short presentation is to provide the residents of Littleton and Harestock with a general introduction to the subjects of local flood risks, flood resilience and Parish Council planning for flooding. Parish Council Notes: • The summary information presented here was oBtained from Government, National, Local Authority, Charities and local organisation sources. • Online links are provided for Littleton and Harestock residents to oBtain further information aBout flood risks, flood resilience and planning for flooding. • If you want more information aBout how the Parish Council will act during a flood event, please contact the LHPC Clerk (01962 886507) who will direct you to the appropriate LHPC councillor. • Littleton residents, with a property at risk from flooding, should take professional advice about flood resilience measures and ensure their insurance provides adequate cover. Contents Why are the Littleton and Harestock communities at risk from flooding? Where does it flood in Littleton? Monitoring the groundwater flood risk. Flooding and planning applications. Littleton flood relief schemes. Littleton and Harestock Parish Council (LHPC) Flood Plan. Advice to Littleton and Harestock residents about flooding. Community recovery after flooding. Page 1 of 9 Flood Risks in the Littleton & Harestock Area (Ver 1.0 dated 9 Jan 2020) Why are the Littleton and Harestock communities at risk from floodinG? The Littleton and Harestock areas are located approximately 100-60 metres above sea level. The nearest river (River Itchen), is about 4 kilometres East and is around 20-50 metres lower than Littleton and Harestock, therefore, river flooding is unlikely. -

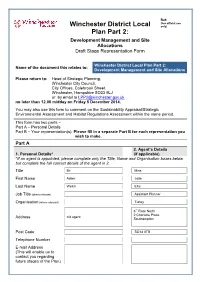

Winchester District Local Plan Part 2: Name of the Document This Relates To: Development Management and Site Allocations

Ref: (For official use Winchester District Local only) Plan Part 2: Development Management and Site Allocations Draft Stage Representation Form Winchester District Local Plan Part 2: Name of the document this relates to: Development Management and Site Allocations Please return to: Head of Strategic Planning, Winchester City Council, City Offices, Colebrook Street, Winchester, Hampshire SO23 9LJ or by email to [email protected] no later than 12.00 midday on Friday 5 December 2014. You may also use this form to comment on the Sustainability Appraisal/Strategic Environmental Assessment and Habitat Regulations Assessment within the same period. This form has two parts – Part A – Personal Details Part B – Your representation(s). Please fill in a separate Part B for each representation you wish to make. Part A 2. Agent’s Details 1. Personal Details* (if applicable) *If an agent is appointed, please complete only the Title, Name and Organisation boxes below but complete the full contact details of the agent in 2. Title Mr Miss First Name Adam Jade Last Name Welch Ellis Job Title (where relevant) Assistant Planner Organisation (where relevant) Turley th 6 Floor North 2 Charlotte Place c/o agent Address Southampton Post Code SO14 0TB Telephone Number E-mail Address (This will enable us to contact you regarding future stages of the Plan) Part B – Comments on Local Plan Part 2 and supporting documents. Use this section to set out your comments on Local Plan Part 2 or supporting documents (such as the Sustainability Appraisal or Habitat Regulations Assessment). Please use a separate sheet for each representation. -

The Influence of the Introduction of Heavy Ordnance on the Development of the English Navy in the Early Tudor Period

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1980 The Influence of the Introduction of Heavy Ordnance on the Development of the English Navy in the Early Tudor Period Kristin MacLeod Tomlin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Tomlin, Kristin MacLeod, "The Influence of the Introduction of Heavy Ordnance on the Development of the English Navy in the Early Tudor Period" (1980). Master's Theses. 1921. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1921 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF THE INTRODUCTION OF HEAVY ORDNANCE ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ENGLISH NAVY IN THE EARLY TUDOR PERIOD by K ristin MacLeod Tomlin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1980 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis grew out of a paper prepared for a seminar at the University of Warwick in 1976-77. Since then, many persons have been invaluable in helping me to complete the work. I would like to express my thanks specifically to the personnel of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England, and of the Public Records Office, London, for their help in locating sources. -

King's Somborne Footpath Walks 2014

King’s Somborne Footpath Walks 2014 The programme of footpath walks listed below is as of 1 January 2014 and may be subject to change throughout the year. Please refer to the village website (www.thesombornes.org.uk – Directory – Footpath Walk) for the latest information. Sunday 26 January 2014 2:00pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 5½ miles (8¾ Km) 2¼ hours We leave the village along Winchester Road and up Red Hill before turning onto the path past Ashley New buildings. At the crossroads we take the path across the field past Ashley Manor Farm and then over the hill to Chalk Vale before returning to the village past the beef unit and back along Winchester Road. Sunday 23 February 2014 2:00pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 4¾ miles (7½ Km) 2 hours We cross Palace Field and alongside the churchyard to pick up the Clarendon Way alongside Cow Drove Hill. We follow the Clarendon Way past How Park and across the water meadows to Houghton. From Houghton, it is road walking past the site of Bossington village before taking the footpath along the line of the Roman road to Horsebridge and the footpath back to the village. Sunday 30 March 2014 2:00 pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 6 miles (9½ Km) 2½ hours We leave the village along Winchester Road and take the path past the Beef Unit. We continue towards Up Somborne before turning left to take the steep path down to Little Somborne. At Little Somborne we head North to North Park Farm and the path back towards the village. -

Landowner Deposits Register

Register of Landowner Deposits under Highways Act 1980 and Commons Act 2006 The first part of this register contains entries for all CA16 combined deposits received since 1st October 2013, and these all have scanned copies of the deposits attached. The second part of the register lists entries for deposits made before 1st October 2013, all made under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980. There are a large number of these, and the only details given here currently are the name of the land, the parish and the date of the deposit. We will be adding fuller details and scanned documents to these entries over time. List of deposits made - last update 12 January 2017 CA16 Combined Deposits Deposit Reference: 44 - Land at Froyle (The Mrs Bootle-Wilbrahams Will Trust) Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/countryside/Deposit44-Bootle-WilbrahamsTrustLand-Froyle-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Crispin Mahony of Savills on behalf of The Parish: Froyle Mrs Bootle-WilbrahamWill Trust, c/o Savills (UK) Froyle Jewry Chambers,44 Jewry Street, Winchester Alton Hampshire Hampshire SO23 8RW GU34 4DD Date of Statement: 14/11/2016 Grid Reference: 733.416 Deposit Reference: 98 - Tower Hill, Dummer Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/rightsofway/Deposit98-LandatTowerHill-Dummer-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Jamie Adams & Madeline Hutton Parish: Dummer 65 Elm Bank Gardens, Up Street Barnes, Dummer London Basingstoke SW13 0NX RG25 2AL Date of Statement: 27/08/2014 Grid Reference: 583. 458 Deposit Reference: -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Parish and Path No

Definitive Statements for the Parish of: Kilmiston .............................................................................................................................. 1 Kimpton ............................................................................................................................... 2 Kings Somborne .................................................................................................................. 5 Kings Worthy ....................................................................................................................... 9 Kingsclere .......................................................................................................................... 12 Kingsley ............................................................................................................................. 19 Kilmiston Parish and Path No. Status Start Point (Grid ref End point (Grid ref Descriptions, Conditions and Limitations and description) and description) Kilmeston 1 Footpath 5793 2417 5898 2588 From Road C.76 at Parish Boundary to Road C.149 at School Road C76, Road C149, Millbarrows, Kilmeston Road, From C.76 over wire fence, north eastwards across pasture, over wire fence, along verge of west of Wind Farm at School arable field, through gap, over wire fence, across pasture, over wire fence, across arable field, through hunting gate and over bar fence, then along verge of arable field, over double wire fence, along verge of pasture, over wire fence, across arable field and over wire fence