Professional Tennis's Constellational Response to COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

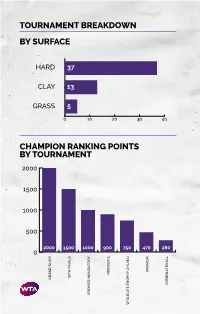

Tournament Breakdown by Surface Champion Ranking Points By

TOURNAMENT BREAKDOWN BY SURFACE HAR 37 CLAY 13 GRASS 5 0 10 20 30 40 CHAMPION RANKING POINTS BY TOURNAMENT 2000 1500 1000 500 2000 1500 1000 900 750 470 280 0 PREMIER PREMIER TA FINALS TA GRAN SLAM INTERNATIONAL PREMIER MANATORY TA ELITE TROPHY HUHAI TROPHY ELITE TA 55 WTA TOURNAMENTS BY REGION BY COUNTRY 8 CHINA 2 SPAIN 1 MOROCCO UNITED STATES 2 SWITZERLAND 7 OF AMERICA 1 NETHERLANDS 3 AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRIA 1 NEW ZEALAND 3 GREAT BRITAIN 1 COLOMBIA 1 QATAR 3 RUSSIA 1 CZECH REPUBLIC 1 ROMANIA 2 CANADA 1 FRANCE 1 THAILAND 2 GERMANY 1 HONG KONG 1 TURKEY UNITED ARAB 2 ITALY 1 HUNGARY 1 EMIRATES 2 JAPAN 1 SOUTH KOREA 1 UZBEKISTAN 2 MEXICO 1 LUXEMBOURG TOURNAMENTS TOURNAMENTS International Tennis Federation As the world governing body of tennis, the Davis Cup by BNP Paribas and women’s Fed Cup by International Tennis Federation (ITF) is responsible for BNP Paribas are the largest annual international team every level of the sport including the regulation of competitions in sport and most prized in the ITF’s rules and the future development of the game. Based event portfolio. Both have a rich history and have in London, the ITF currently has 210 member nations consistently attracted the best players from each and six regional associations, which administer the passing generation. Further information is available at game in their respective areas, in close consultation www.daviscup.com and www.fedcup.com. with the ITF. The Olympic and Paralympic Tennis Events are also an The ITF is committed to promoting tennis around the important part of the ITF’s responsibilities, with the world and encouraging as many people as possible to 2020 events being held in Tokyo. -

Hubert Hurkacz of Poland and Ashleigh Barty of Australia Wins

Price 1999 -> 20% off -> 1599 Daily Current Affairs @8AM Live News Time Daily Current Affairs @8AM Live International News ➢ Forbes’ annual world’s billionaires :35th edition Forbes World’s Billionaires list was released on April 06, 2021, comprising a record-breaking 2,755 billionaires. ▪ The Amazon.com Inc founder Jeff Bezos has topped the Forbes’ annual world’s billionaires list for the fourth consecutive year. ▪ India’s richest billionaire Mukesh Ambani ranked at 10th position with total net worth of USD 84.5 billion. ▪ The list is prepared based on the wealth using stock prices and exchange rates from March 5, 2021. Daily Current Affairs @8AM Live International News ➢ Forbes’ annual world’s billionaires Net Worth in USD Rank Name Company ($) 1 Jeff Bezos Amazon 177 billion 2 Elon Musk Tesla, SpaceX 151 billion 3 Bernard Arnault LVMH 150 billion 4 Bill Gates Microsoft 124 billion 5 Mark Zuckerberg Facebook 97 billion 10 Mukesh Ambani Reliance Industries 84.5 billion Daily Current Affairs @8AM Live Banking News ▪ The senior-most deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India, Shri BP Kanungo has retired upon completion of his one-year extension on April 02, 2021. ▪ भारतीय रर焼र् व बकℂ के र्ररष्ठतम डिप्टी गर्र्रव श्री बीपी कार्ूर्गो 02 अप्रैल, 2021 को अपर्ा एक साल का कायकव ाल पूरा करर्े के बाद सेर्ानर्र्त्तृ हो गए। ▪ During his four-year term as deputy governor, Kanungo was in charge of currency management, external investments, operations, payment, and settlement system, among others. ▪ Other deputy governors are Rajeshwar Rao, M.K. -

Peace Negotiators Continue Discussions on Work Plans for Union Peace Conference Next Month

SO THIS IS A MUST. PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL MoHS officials inspect broadcast media, MoALI organizes 98th International Day sample film shooting to enforce healthcare of Cooperatives in Nay Pyi Taw guidelines PAGE-2 PAGE-3 Vol. VII, No. 80, 1st Waning of First Waso 1382 ME www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Sunday, 5 July 2020 Peace negotiators continue discussions on work INSIDE TODAY plans for Union Peace Conference next month NATIONAL Asia-Pacific YMCA Executive Committee holds meeting online PAGE-3 NATIONAL Phakant landslide investigation body gives assistance to victims PAGE-4 NATIONAL 41 Myanmar migrant workers enter into facility quarantine in Kawthoung Peace negotiators discuss fourth session of Union Peace Conference scheduled for second week of August after the sixth coordination meeting in PAGE-4 last week of July. PHOTO: PHOE HTAUNG EPRESENTATIVES Road in Yangon yesterday. U Pyone Cho (a) U Htay Win ordinator U Myo Win, and mem- LOCAL NEWS of the government and Present on the govern- Aung, members of the Peace bers of negotiation team U Hla Fake Thanaka from RNCA-S EAOs continued ment’s side at the meeting were Commission Advisory Board U Htay, Saw Mya Yar Zar Lin, Dr neighbouring country discussions on the work plans the NRPC Vice-Chairman and Hla Maung Shwe, U Moe Zaw Salai Lian Hmon Sakhong, Salai impacts local genuine for holding the fourth session Attorney-General of the Union Oo and Director-General of the Htarlar Hay, Saw Sein Win, Pado Thanaka growers of Union Peace Conference-21st U Tun Tun Oo, Lt-Gen Yar Pyae Office of the State Counsellor U Saw Tar Do Hmu, Pado Saw L Century Panglong scheduled for of the Office of the Command- Zaw Htay. -

Project Report Porsche Tennis Grand Prix

06/15 Project report Porsche Tennis Grand Prix www.conica.com PROJECT CHALLENGE THE PORSCHE TENNIS WTA INDOOR TENNIS GRAND PRIX ON CLAY COURTS Eight days, total concentration and the best female tennis In 2009, the Porsche Tennis Grand Prix kicked off a new players in the world on the court. The Porsche Tennis Grand era. With an annual indoor tournament on clay courts, Prix, held in the famous Porsche Arena in Stuttgart, is one of the event offered the best female professional tennis the top events in the world of professional tennis. In 1977, a players in the world the perfect opportunity to prepare gala with four professional players was held at indoor courts for the clay season. in Filderstadt-Plattenhardt. This idea led to the first tourna- ment in 1978, which later evolved to become the WTA tourna- The challenge: creating a clay court system that can ment in Filderstadt. Today, the Porsche Tennis Grand Prix is adapt to the technical and environmental conditions of one of the longest-running tournaments on the Women’s Tour an indoor facility and is also easy to install before the and features some of the best players in the world of tennis, tournament and remove afterwards. Furthermore, the making it a premier event on the WTA tour. The Porsche Tennis system must offer ideal clay court conditions – from Grand Prix represents precision, athleticism, competitive spirit the first to the last rally. and excellent technique on a perfect court. FACTS 2015 FEATURES 8 PLAYERS FROM THE TOP 10 AND 13 PLAYERS FROM THE TOP 20 HIGHEST WTA TOURNAMENT CATEGORY AFTER THE FOUR GRAND SLAM TOURNAMENTS SELECTED NUMEROUS TIMES BY THE PLAYERS AS THEIR FAVOURITE WTA TOURNAMENT TOTAL PRIZE MONEY: 731 000 US DOLLARS 37 200 SPECTATORS SOLUTION RESULT CONIPUR® PRO CLAY PERFECT CONDITIONS, FROM CONICA THRILLING TENNIS CONIPUR® PRO CLAY is a clay court system for indoor and The Porsche Tennis Grand Prix 2015 offered the spectators outdoor tennis. -

How the Court Surface Is Affecting the Serve-And-Volley Tristan Barnett

How the court surface is affecting the serve-and-volley Tristan Barnett Strategic Games www.strategicgames.com.au 1. Introduction The modern version of the game (official name of Lawn Tennis) as we recognize it today was designed and patented by Major Walter Clopton Wingfield in 1873. Two years later in 1875, the official rules of the game were drawn up by Marylebone Cricket Club, and two years later in 1877, Wimbledon began on a grass surface as the first official championships. All four grand slam events have been played on a grass surface. Wimbledon is the only grand slam event played on a grass court today and has always been played on a grass court surface. The French Open began in 1891 on a grass surface and remained on grass until 1928 when the surface was changed to clay. The US Open began in 1881 on a grass surface; until it was changed to clay from 1975-1977 and from 1978 has been played on a hard court surface. Finally, the Australian Open began in 1905 on a grass surface and remained on grass until 1988 when the surface was changed to a hard court. There has been a change in the proportion of tournaments played on different court surfaces from 1877 to 2010. Firstly, for the first 14 years of the game, all tournaments (grand slam and non grand slam) were played on grass. Secondly, for the first 101 years of the game all tournaments were played on the natural surfaces of grass and clay. Thirdly, according to the ITF, until the early 1970’s, the majority of tournaments were played on grass including three out of the four grand slams. -

Player Perceptions and Biomechanical Responses to Tennis Court Surfaces: the Implications to Technique and Injury Risk

PLAYER PERCEPTIONS AND BIOMECHANICAL RESPONSES TO TENNIS COURT SURFACES: THE IMPLICATIONS TO TECHNIQUE AND INJURY RISK Submitted by Chelsea Starbuck, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sport and Health Sciences September 2014 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract Elite tennis players are required to perform on a variety of tennis court surfaces which differ in mechanical characteristics, such as friction and hardness, influencing their performance and risk of injury. To understand the influence of surfaces on performance and injury risk, three studies were conducted to investigate tennis players’ perceptions and biomechanical responses during tennis-specific movements on different court surfaces. In study 1, tennis players perceptions of acrylic and clay courts were identified following a thematic inductive analysis of semi-structured interviews (n = 7) to develop of a series of visual analogue scales (VAS) to quantify perceptions during studies 2 and 3. Perceptions of predictability of the surface and players’ ability to slide and change direction emerged, in addition to anticipated perceptions of grip and hardness. Study 2 aimed to examine the influence of court surfaces and prior clay court experience on perceptions and biomechanical characteristics of tennis-specific skills. -

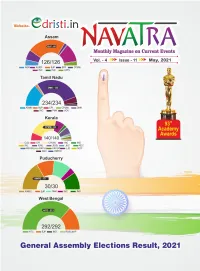

Edristi-Navatra-April-2021.Pdf

Preface Dear readers, we have started edristi English edition as well since August, 2015. We are hopeful that it will help us to connect to the broader audience and amplify our personal bonding with each other. While presenting Day-to-day current affairs, we are very cautious on choosing the right topics to make sure only those get the place which are useful for competitive exams perspective, not to increase unnecessary burden on the readers by putting useless materials. Secondly, we have also provided the reference links to ensure its credibility which is our foremost priority. You can always refer the links to validate its authenticity. We will try to present the current affairs topics as quickly as possible but its authenticity is given higher priority over its turnaround time. Therefore it could happen that we publish the incident one or two days later in the website. Our plan will be to publish our monthly PDF on very first day of every month with making appropriate modifications of day-to-day events. In general, the events happened till 29th day will be given place in the PDFs. The necessity of this is to ensure the contents factual authenticity. Reader’s satisfaction is our utmost priority so requesting you to provide your valuable feedback to us. We will warmly welcome your appreciation/criticism given to us. It will surely show us the right direction to improve the content quality. Hopefully the current affairs PDF (from 1st March to 31st March) will benefit our beloved readers. Current affairs data will be useless if it couldn’t originate any competitive exam questions. -

Florida Women's Tennis

2013-14 Gators (back row, left-to-right): Head Coach Roland Thornqvist, Brianna Morgan, Kourtney Keegan, Stefani Stojic, Belinda Woolcock and Associate Head Coach Dave Balogh; (front row) Program Coordinator Kate Harte, Olivia Janowicz, Sofie Oyen, Alexandra Cercone and Graduate Assistant Athletic Trainer Kelly Needs FLORIDA WOMEN’S TENNIS 2013-14 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT FLORIDA WOMEN’S TENNIS 2013-14 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT CONTENTS / QUICK FACTS 2013-14 SEASON PREVIEW 2013-14 Gator Roster ......................................................3 FLORIDA TENNIS QUICK FACTS (as of Jan. 1, 2014) 2013-14 Gator Schedule ..................................................2 Perry Indoor Facility ........................................................93 G eneral Information SEC Academic Honor Roll (5): .... Alexandra Cercone, Lauren Embree, Caroline Hitimana, Olivia Janowicz, Sofie Oyen Ring Tennis Complex ......................................................91 Location: ......................... Gainesville, Florida UF Quick Facts ................................................................1 SEC Freshman Academic Honor Roll (1): .....Brianna Morgan Est. Population: .............................124,491 ITA Scholar-Athlete (min. 3.5 GPA): ...... Alexandra Cercone MEDIA INFORMATION Founded: ....................................1853 ITA All-Academic Team (minimum 3.2 team GPA): .......yes! Communications Directory, UF ..........................................4 Enrollment: ................................49,785 Directions to Tennis Complex ............................................6 -

Characterisation of Ball Degradation Events in Professional Tennis

Sports Eng DOI 10.1007/s12283-017-0228-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Characterisation of ball degradation events in professional tennis 1,2,3 1 3 1 Ben Lane • Paul Sherratt • Xiao Hu • Andy Harland Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Tennis balls are acknowledged to degrade with appears to influence the distribution of ball speed on impact use and are replaced at regular intervals during professional with the surface or racket, suggesting a surface-specific matches to maintain consistency and uniformity in per- degradation test may be beneficial. As a result of these formance, such that the game is not adversely affected. findings a new test protocol has been proposed, utilising the Balls are subject to the international tennis federation’s in-play data, to define the frequency of impacts and impact (ITF) ball approval process, which includes a degradation conditions to equate to nine games of professional tennis test to ensure a minimum standard of performance. The across the different surfaces. aim of this investigation was to establish if the ITF degradation test can assess ball longevity and rate of Keywords Tennis Á Ball Á Impact Á Hawk-Eye Á Surface Á degradation and determine if there is a need for a new Speed Á Angle Á Degradation degradation test that is more representative of in-play conditions. Ball tracking data from four different profes- sional events, spanning the three major court surfaces, 1 Introduction including both men’s and women’s matches were analysed. The frequency of first serves, second serves, racket impacts Approximately 360 million tennis balls are manufactured and surface impacts were assessed and the corresponding each year [1], with wholesale sales figures in the region of distribution of ball speed and (for surface impacts) impact $92 million in the United States alone in 2015 [2]. -

Two Virus Cases Raise Questions Over Djokovic Tournament

NBA | Page 4 RUGBY | Page 5 Hawks recognise How Mandela improvement inspired Pienaar, on defense so Boks to conquer ‘crucial’ the world Tuesday, June 23, 2020 FOOTBALL Dhul-Qa’da 2, 1441 AH Mourinho hits back GULF TIMES at Merson’s criticism of playing style SPORT Page 3 TENNIS Two virus cases raise questions over Djokovic tournament Croatia’s Coric too tests positive for Covid-19; Zverev and Cilic test negative Murray says priority is to play at AFP US Open and French Open Paris, France Reuters “I don’t mind what the situation New York, United States is, providing it is safe. If I was orna Coric said yester- told I could take one person day he had become the with me... you can make that second player to test ormer world number work. I’d probably go with a positive for coronavirus, one Andy Murray says physio and some coaching B he is looking forward to could be done remotely.” prompting growing questions F about an exhibition tournament competing at the US Open and The ATP and WTA Tours are set in the Balkans featuring world French Open later this year but to resume in August but the number one Novak Djokovic. only if it is safe enough amid spotlight is on the sport after “Hi everyone, I wanted to in- the Covid-19 pandemic that Grigor Dimitrov and Borna form you all that I tested posi- shut down the sport in March. Coric tested positive following tive for Covid-19,” the Croatian, The US Open will be staged their participation in Djokovic’s ranked 33rd in the world, posted without fans as scheduled from Adria Tour exhibition tourna- on Twitter. -

2020 Women’S Tennis Association Media Guide

2020 Women’s Tennis Association Media Guide © Copyright WTA 2020 All Rights Reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced - electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopying- without the written permission of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA). Compiled by the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Communications Department WTA CEO: Steve Simon Editor-in-Chief: Kevin Fischer Assistant Editors: Chase Altieri, Amy Binder, Jessica Culbreath, Ellie Emerson, Katie Gardner, Estelle LaPorte, Adam Lincoln, Alex Prior, Teyva Sammet, Catherine Sneddon, Bryan Shapiro, Chris Whitmore, Yanyan Xu Cover Design: Henrique Ruiz, Tim Smith, Michael Taylor, Allison Biggs Graphic Design: Provations Group, Nicholasville, KY, USA Contributors: Mike Anders, Danny Champagne, Evan Charles, Crystal Christian, Grace Dowling, Sophia Eden, Ellie Emerson,Kelly Frey, Anne Hartman, Jill Hausler, Pete Holtermann, Ashley Keber, Peachy Kellmeyer, Christopher Kronk, Courtney McBride, Courtney Nguyen, Joan Pennello, Neil Robinson, Kathleen Stroia Photography: Getty Images (AFP, Bongarts), Action Images, GEPA Pictures, Ron Angle, Michael Baz, Matt May, Pascal Ratthe, Art Seitz, Chris Smith, Red Photographic, adidas, WTA WTA Corporate Headquarters 100 Second Avenue South Suite 1100-S St. Petersburg, FL 33701 +1.727.895.5000 2 Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Women’s Tennis Association Story . 4-5 WTA Organizational Structure . 6 Steve Simon - WTA CEO & Chairman . 7 WTA Executive Team & Senior Management . 8 WTA Media Information . 9 WTA Personnel . 10-11 WTA Player Development . 12-13 WTA Coach Initiatives . 14 CALENDAR & TOURNAMENTS 2020 WTA Calendar . 16-17 WTA Premier Mandatory Profiles . 18 WTA Premier 5 Profiles . 19 WTA Finals & WTA Elite Trophy . 20 WTA Premier Events . 22-23 WTA International Events . -

Countrywide Classic USTA Men's Challenger and the Home Depot

Countrywide Classic USTA Men’s Challenger and The Home Depot Center USTA Women’s Challenger Pro Circuit Tournament Features Tennis’ Rising Stars The Home Depot Center to Host $50,000 Purse Tournament May 28 – June 3 CARSON, Calif., May 7, 2007 – The United States Tennis Association (USTA) today announced that The Home Depot Center in Carson, Calif., will host the Countrywide Classic USTA Men’s $50,000 Challenger and The Home Depot Center USTA Women’s $50,000 Challenger Monday, May 28 through Sunday, June 3. This is one of four combined tournaments on the USTA Pro Circuit scheduled for 2007. This year’s event marks the second time Carson has hosted a men’s challenger and is the inaugural event for the women. The Challenger tournament offers an opportunity for players to gain professional ranking points needed to compete on major tours. Players ranked as high as No. 50 in the world typically compete in challenger-level events. In 2005, Justin Gimelstob, a winner of nine professional titles, won the inaugural men’s event. Gimelstob has captured 13 ATP Tour doubles championships. Both fields will feature 32 singles players and 16 doubles teams, drawing from the Top 200 tennis world rankings. Men’s singles qualifying will take place on Saturday, May 26, while the women’s is slated for Sunday, May 27. The event is free to the public Monday, May 28 – Saturday, June 2. On Sunday, June 3, tickets to the finals are $5.00. For more information, please visit www.usta.com/carsonchallenger. The event will also offer a free Kids Day on Saturday, June 2 at The Home Depot Center from 9:00 a.m.