Fragility and State-Society Relations in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minister's Letter

LGreenbank Parish e Church a f l e t Braidburn Terrace, EH10 6ES Minister’s Letter No 619 September 2012 Pulpit Diary Dear Friends Aug 31 Friday Yesterday saw the closing cer- for him. And they did. Just emony of the London 2012 days before the Olympics 7.30pm Pre-communion Service Olympic Games. Over the last began the International 16 days many names previ- Olympic Committee agreed ously unknown have become that he could run as an inde- Sept 2 household icons. There is pendent athlete under their 9.00am Communion however one name that is per- flag. The US and British -au 10.30am Communion haps not so well known. That thorities processed the nec- is the name of Guor Marial. essary papers in record time. Springboard and Spectrum meet Marial did not power his way The IOC paid his ticket to as usual to gold in the swimming pool, London. 3.00pm Communion (Braid Room) nor did he ride to victory at An Olympic medal for Mari- Greenwich. He did not mount al was probably never a real- the podium in the athletics istic prospect. He had none Sept 9 stadium. Nor did he receive of the advantages of his com- 10.30am Morning Worship the acclaim of the velodrome. petitors. He works nights in In fact Marial came 47th in the a home for mentally disabled one event which he entered – the men’s mara- adults. Most of his training is along roads and Sept 16 thon. Yet his story can and should inspire and trails. -

January 2015 Track and Field Writers of America in This Issue

January 2015 Track and Field Writers of America In this issue: (Founded June 7, 1973) PRESIDENT Jack Pfeifer, 6129 N. Lovely St., Portland, OR 97203. Office/home: 917- 579-5392. Email: P. 2 President’s Message [email protected] P. 3 TAFWA/Armory Foundation Book Award Finalists VICE PRESIDENT Doug Binder. Email: P.4 TAFWA/Bud Greenspan Documentary Award Finalists [email protected]. P. 5 Cheryl Treworgy Update @ garycohenrunning.com Phone: 503-913-4191. P. 8 Qatar Fills the Stands with Paid Fans TREASURER Tom Casacky, P.O. Box P. 10 Kristi Anderson, Masters Runner, Bewildered Over 4288, Napa, CA 94558. Phone: 818-321-3234. Drug Suspension Email: [email protected] P. 12 Update on Liz McColgan-Nuttall SECRETARY/ P. 14 USC Crowd Funds for Zamperini Scholarship AWARDS CHAIR Don Kopriva, 5327 New- P. 15 Catching Up With Amy Yoder Begley port Drive, Lisle IL 60532. Home: 630-960-3049. P. 20 Jeff Mason, Boulder Marathon Director, Sued Cell: 630-712-2710. P. 21 Drummond Gets 8 Year Doping Suspension Email: donkopriva777@ aol.com P. 23 Bob Gourley Receives the National Throws Coach Award NEWSLETTER EDITOR P. 24 FAST Compilation by Rey O’Neal: NCAA Division I Kim Spir, University of Portland, 5000 N. Finalists Top Eight - Organization of Eastern Willamette Blvd., Caribbean States Portland, OR 97203. Work: 503-943-7314. P. 26 Elfriede Prefontaine Dies at Age 88 Email: kim.spir@gmail. com P. 29 Guor Marial Suspended by South Sudan P. 30 Coach Brooks Johnson Speaks Out FAST Dave Johnson. Email: P. 33 Excerpt from “A Ride for Robert” by Mark Cullen [email protected] Phone: 215-898-6145. -

US Routs Argentina 105-78, Moves Into MEN's Semis

Sports FRIDAY, AUGUST 19, 2016 Former slave to run for S Sudan in marathon ATHLETICS LONDON: South Sudanese Olympic athlete Guor Marial may not be a hot medal tip for Sunday’s marathon, but the former slave’s road to Rio is one of the most astonishing stories of the games. As a teenager Marial was forced to run for his life during Sudan’s long civil war in which he lost 28 members of his family, was kidnapped twice and end- ed up in servitude. When he fled Sudan he never wanted to run again because of the traumatic memories, but after arriving in the United States as a refugee his talent was quickly spotted by his teachers. RIO DE JANEIRO: United States’ Carmelo Anthony (15) shoots in front of Argentina’s Andres Nocioni, right, during a quarterfinal round This month Marial made history when basketball game at the 2016 Summer Olympics. — AP he became the flag-bearer for South Sudan’s first ever Olympic team, leading his compatriots Margret Hassan and Santino Kenyi into Rio’s Maracana stadium during US routs Argentina 105-78, the opening ceremony. Rio is Marial’s sec- ond Olympics, but it is the first in which he can wear his national colors. In London four years ago he had to compete as an inde- moves into men’s semis pendent under the Olympic flag because South Sudan - which had only gained inde- pendence the year before - was unable to tional competition after the game, 12 years after 2008 final and 107-100 four years ago in London. -

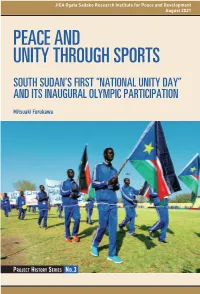

Peace and Unity Through Sports South Sudan’S First “National Unity Day” and Its Inaugural Olympic Participation

JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development August 2021 PEACE AND UNITY THROUGH SPORTS SOUTH SUDAN’S FIRST “NATIONAL UNITY DAY” AND ITS INAUGURAL OLYMPIC PARTICIPATION Mitsuaki Furukawa PROJECT HISTORY SERIES No.3 Peace and Unity through Sports South Sudan’s First “National Unity Day” and its Inaugural Olympic Participation Mitsuaki Furukawa 2021 JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development Cover: March at South Sudan’s First national sports event “National Unity Day” (Photograph courtesy of Ayako Oi) The author would like to thank Drs. Robert D. Eldridge and Graham B. Leonard for their translation of this work. The views and opinions expressed in the articles contained in this volume do not necessarily represent the official view or positions of the organizations the authors work for or are affiliated with. JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development https://www.jica.go.jp/jica-ri/index.html 10-5 Ichigaya Honmura-cho, Shinjuku-ku Tokyo 162-8433, JAPAN Tel: +81-3-3269-2357 Fax +81-3-3269-2054 Copyright@2020 JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development. ISBN: 978-4-86357-088-7 Foreword This book is about the efforts to promote “Peace and Unity” through sports in the Republic of South Sudan following its independence in 2011. The author, Mitsuaki Furukawa, was involved throughout this process as the Chief Representative, JICA South Sudan Office. The book records the struggle of one Japanese person, along with a great many South Sudanese people, who held out the hope of realizing Peace and Unity in a country that had seen more than 50 years of conflict, both before and after its independence. -

Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers Receive Ramon

JICA USA Newsletter – July/August 2016 The JICA USA Newsletter is a bi-monthly publication which provides information on JICA’s activities in Washington, DC and around the world. If you are interested in receiving this electronic newsletter, please contact [email protected] to be added to our mailing list. In this issue: Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers receive Ramon Magsaysay Award JDR Infectious Diseases Response Team dispatched for Yellow Fever Outbreak JICA provides financial support for South Sudan’s participation in Olympics Vocational training in Paraguay and Angola: Japan-Brazil collaboration __________________ Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers receive Ramon Magsaysay Award On July 27, the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation announced the Japanese Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV) as one of the six recipients of the 2016 Ramon Magsaysay Award. This award, which was established in 1957 in memory of the third Philippine President, is considered Asia’s equivalent to the Nobel Peace Prize and is one of Asia’s premier prizes and highest honors. This year, the Ramon Magsaysay Award recognizes JOCVs for their integrity in public service and pragmatic idealism toward advancing the lives of developing communities. The experiences and purpose of the JOCVs well align with the mission of the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation which seeks to honor organizations and individuals who exemplify “selfless leadership and manifest greatness of spirit in service to the people of Asia.” The Japanese government established the JOCV Program in Ramon Magsaysay Award Emblem 1965 in order to give back to the international community after Japan’s aggressions in World War II. Administered under the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the JOCVs mission is to use grassroots diplomacy and community engagement to help facilitate the economic and social development of international countries in need. -

Cyclone Olympians

CYCLONE OLYMPIANS 1928 - AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS 1992 - BARCELONA, SPAIN Ray Conger (United States) 1,500-Meter Run (10th) Maria Akraka (Sweden) 1,500-Meter Run (SF) Yobes Ondieki (Kenya) 5,000-Meter Run (Fifth) 1976 - MONTREAL, CANADA Clive Sands (Bahamas) 100-Meter Dash (R1) 1996 - ATLANTA, UNITED STATES 200-Meter Dash (R1) Jon Brown (Great Britain) 10,000-Meter Run (10th) 4x100-Meter Relay (Semifinals) John Nuttall (Great Britain) 5,000-Meter Run (SF) Suzanne Youngberg (Great Britain) Marathon (58th) 1980 - MOSCOW, U.S.S.R *David Korir (Kenya) 800-Meter Run 2000 - SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA *James Moi (Kenya) Long Jump Jon Brown (Great Britain) Marathon (Fourth) Triple Jump Sunday Uti (Nigeria) 4x400-Meter Relay (Fifth) 2004 - ATHENS, GREECE Jon Brown (Great Britain) Marathon (Fourth) *Indicates athletes who qualified, but did not compete due Aurelia Trywianska (Poland) 100-Meter Hurdles (R1) to boycott. 2008 - BEIJING, CHINA 1984 - LOS ANGELES, UNITED STATES Aurelia Trywianska-Kollash (Poland) 100-Meter Hurdles (SF) Nawal El Moutawakel (Morocco) 400-Meter Hurdles (Gold) Danny Harris (USA) 400-Meter Hurdles (Silver) 2012 - LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM Henrik Jorgensen (Denmark) Marathon (19th) Lisa Uhl (USA) 10,000-Meter Run (13th) Moses Kiyai (Kenya) Long Jump (16th) Guar Marial (Independent) Marathon (47th) Triple Jump (20th) Dorthe Rasmussen (Denmark) Marathon (13th) 2016 - RIO DE JANIERO, BRAZIL Sunday Uti (Nigeria) 400-Meter Dash (Sixth) Hillary Bor (USA) 3,000-Meter Steeplechase (Eighth) 4x400-Meter Relay (Bronze) Mohamed Hrezi (Libya) Marathon -

IOC NEWSLETTER Permanent Observer Office to the United Nations

NEWSLETTER 05 SEPTEMBER 2012 OLYMPIC.ORG IOC NEWSLETTER Permanent Observer Office to the United Nations UN appeals for Olympic Truce during London 2012 Games UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and President of the 66th UN General Assembly, Nassir Abdulaziz Al-Nasser, called on all UN Member States to observe the traditional Olympic Truce, from the start of the Games of the XXX Olympiad on 27 July until the close of the XIV Paralympic Games on 9 September in London. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon meets IOC President Jacques Rogge in London after participating in the Olympic Torch Relay through the centre of the British capital. See p2. In his message, the UN Secretary-General recalled that “today, sports and events Features such as the Olympic and Paralympic Games break down barriers by bringing together people from all over the world and all walks of life. The participants may carry the flags of many nations, but they come together under the shared banner of equality and fair play, understanding and mutual respect.” The UN General Assembly President, Mr Al-Nasser, noted that “the Olympic Movement aspires to contribute to a peaceful future for all humankind through the educational value of PAGE 2 sport. The Games will bring together athletes Torch Relay’s from all parts of the world in the greatest of Moment To Shine international sports events as a means to promote peace, mutual understanding and goodwill among nations and peoples – goals that are also part of the founding values of the United Nations.” Full text of UN Secretary-General’s message PAGE 3 Full text of UN GA President’s Sustainability is a message key legacy for every Olympic Games The UN Olympic Truce Resolution for the 2012 Games was presented by the Chair of the London Olympic Games Organising Committee, Sebastian Coe, on behalf of the UK government and made history by Athletes and officials showed their support for becoming the first-ever UN resolution to be the Truce by signing the Olympic Truce Wall in the Olympic Village co-sponsored by all 193 UN Member States. -

MEDIA MONITORING REPORT United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS)

Media & Spokesperson Unit, Communication & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) WEDNESDAY, 20 MARCH 2013 SOUTH SUDAN • Attack in Jonglei leaves 80 wounded: ICRC (Gurtong.net) • Jonglei security has normalized: Governor (Gurtong.net) • Security stable in Pibor after rebels clash with army (Catholic Radio Network) • Wau protester detainees on hunger strike to demand trial (Voice of Radio) • Unity state recovers over 100 cattle from Misseriya youth (Sudantribune.com) • Minister urges parliamentarians to be watchful of contracts (Gurtong.net) • Convoy takes South Sudanese home from Khartoum (Agence France Presse (AFP) • Health Ministry, partners renew fight against Malaria (Sudantribune.com) • The fight against drought should be intensified, says minister (Gurtong.net) • German firm ready to invest in urban development (Radio Bakhita) • Campaign launched to fund documentary on South Sudan’s first Olympian (Sudantriubne.com) • Education minister announces reforms for the year 2013-2014 (Gurtong.net) • Kapoeta South County Community resource center nears completion (Gurtong.net) • SPLA completes 60 percent borders withdrawal (Catholic Radio Network) SOUTH SUDAN, SUDAN • Sudan and S. Sudan agree to form committee on rebels’ issue (Sudantribune.com) • Four civilians killed by SLA-MM rebels in South Darfur (Sudantribune.com) OTHER HIGHLIGHTS • Former Sudan Airway officials may face criminal charges over Heathrow case (Sudantriune.com) • Sudan’s Bashir confirms he will stand down by 2015 -

Trouble Tomorrow by Terry Whitebeach and Sarafino Enadio

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers’ Notes by Joy Lawn Trouble Tomorrow by Terry Whitebeach and Sarafino Enadio ISBN 9781760291464 Recommended for ages 13-18 yrs These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ............................................ 2 Topics and themes .......................... 2 Plot summary ................................. 2 Curriculum alignment ............................... 3 Activities for the English classroom ............ 3 Orientation to Sudan ....................... 3 Literature and context ..................... 5 Writing .......................................... 9 Story ........................................... 10 Sudanese people in Australia .......... 10 Resources and Further Reading ............... 11 About the writers .................................. 13 The collaborative writing process ............. 14 Blackline masters .................................. 15 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION Trouble Tomorrow is a young adult novel, based on a true story, and is suitable for study in Years 7-10. It follows the life of 16-year old Sudanese boy Obulejo, whose life is turned upside down by civil war. Forced to flee rebel soldiers, he must make his way to a refugee camp over the border, losing all contact with his family and friends along the way. In the camp, he is safer but has no future – until he joins a pioneering peace education program and begins to find ways to create a more hopeful life for himself and others. This book is a useful educational resource, not only addressing topics around war and peace but also giving insights into life within refugee camps, and the resourcefulness and resilience needed by the people who live there. -

Independence Parties in Subnational Island Jurisdictions

Edinburgh Research Explorer Introduction Citation for published version: Baldacchino, G & Hepburn, E 2012, 'Introduction', Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 395-402. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2012.729725 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/14662043.2012.729725 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Commonwealth and Comparative Politics Publisher Rights Statement: © Baldacchino, G., & Hepburn, E. (2012). Introduction. Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, 50(4), 395- 402doi: 10.1080/14662043.2012.729725 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 © Baldacchino, G., & Hepburn, E. (2012). Introduction. Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, 50(4), 395- 402doi: 10.1080/14662043.2012.729725 Independence Parties in Subnational Island Jurisdictions Godfrey Baldacchino and Eve Hepburn (editors) Abstract: Keywords: independence, islands, nationalism, sovereignty, political parties, subnational jurisdiction Editorial With the independence of South Sudan in 2011, the United Nations (UN) now has 193 members; but the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has 204 ‘National Olympic Committees’ (NOCs) within its membership. -

Iowa State Daily (July 26, 2012) Iowa State Daily

Iowa State Daily, July 2012 Iowa State Daily, 2012 7-26-2012 Iowa State Daily (July 26, 2012) Iowa State Daily Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastatedaily_2012-07 Recommended Citation Iowa State Daily, "Iowa State Daily (July 26, 2012)" (2012). Iowa State Daily, July 2012. 4. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastatedaily_2012-07/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State Daily, 2012 at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Iowa State Daily, July 2012 by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cardinal and Olympic THU JUL 26, 2012 Gold London Photo: Katelynn McCollough/Iowa State Daily, Athletes: File photos: Iowa State Daily Athletes: File photos: Iowa State Daily, Photo: Katelynn McCollough/Iowa London Volume 207 | Number 162 | 40 cents | An independent student newspaper serving Iowa State since 1890. | www.iowastatedaily.com • 2 games for $8 + free shoe rental THURSDAY PARTY ON THE PATIO • 2fer domestic draws $1 Miller Lite Draws (7-10pm) • 2fer 8’’ & 16’’ pizzas 1320 Dickinson Ave $2 Draws of Summer Shandy (7-10pm) • Games 1/2 price (6pm-Midnight) 515-598-BOWL (2695) $1 Hamburgers and Hotdogs (7-10pm Patio only) • Buy 2 get 1 free laser tag perfectgamesinc.com Bags on the Patio 2 | TABLE OF CONTENTS | Iowa State Daily | Thursday, July 26, 2012 Table of contents 3.....Poll: Will you watch the Olympics? 12 ...Hill remembers his Olympic glory 4.....One-on-one: Lisa Uhl 18...Calendar: Daily by the day 8.....Editorial: Catch the spirit of Team USA 24...Classifieds 10 ...Danny Harris’ second chance 26...Games Ames, ISU Police Daily scoop Police blotter Departments The team also received awards for best me- The information in the log comes from the ISU and City of Ames police departments’ records. -

Olympism in Action Sport Serving Humankind

June 2013 Olympism in Action Sport Serving Humankind Department of International Cooperation and Development Olympism in Action – Sport Serving Humankind Cover Photo Credit: IOC International Olympic Committee, June 2013 1 Olympism in Action – Sport Serving Humankind Olympism in Action Sport Serving Humankind Contents Message By Jacques Rogge, President of the International Olympic Committee .................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 By T. A. Ganda Sithole, Director of the Department of International Cooperation and Development. ................... 7 1.1 The IOC and the UN ............................................................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Relations with UN family ...................................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Development through sport................................................................................................................................... 8 1.4 Sport for peace ...................................................................................................................................................... 8 1.5 Humanitarian actions ........................................................................................................................................