Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Legacy Regained: Niko and the Russian Avant-Garde

A LEGACY REGAINED: NIKO AND THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE PALACE EDITIONS Contents 8 Foreword Evgeniia Petrova 9 Preface Job de Ruiter 10 Acknowledgements and Notes to the Reader John E. Bowlt and Mark Konecny 13 Introduction John E. Bowlt and Mark Konecny Part I. Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Russian Avant Garde Remembering Nikolai Khardzhiev 21 Nikolai Khardzhiev RudolfDuganov 24 The Future is Now! lra Vrubel-Golubkina 36 Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Suprematists Nina Suetina 43 Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Maiakovsky Museum, Moscow Gennadii Aigi 50 My Memoir of Nikolai Khardzhiev Vyacheslav Ivanov 53 Nikolai Khardzhiev and My Family Zoya Ender-Masetti 57 My Meetings with Nikolai Khardzhiev Galina Demosfenova 59 Nikolai Khardzhiev, Knight of the Avant-garde Jean-C1aude Marcade 63 A Sole Encounter Szymon Bojko 65 The Guardian of the Temple Andrei Nakov 69 A Prophet in the Wilderness John E. Bowlt 71 The Great Commentator, or Notes About the Mole of History Vasilii Rakitin Writings by Nikolai Khardzhiev Essays 75 Autobiography 76 Poetry and Painting:The Early Maiakovsky 81 Cubo-Futurism 83 Maiakovsky as Partisan 92 Painting and Poetry Profiles ofArtists and Writers 99 Elena Guro 101 Boris Ender 103 In Memory of Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov 109 Vladimir Maiakovsky 122 Velimir Khlebnikov 131 Alexei Kruchenykh 135 VladimirTatlin 137 Alexander Rodchenko 139 EI Lissitzky Contents Texts Edited and Annotated by Nikolai Khardzhiev 147 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introductions to Kazimir Malevich's Autobiography (Parts 1 and 2) 157 Kazimir Malevieh Autobiography 172 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Mikhail Matiushin's The Russian Cubo-Futurists 173 Mikhail Matiushin The Russian Cubo-Futurists 183 Alexei Morgunov A Memoir 186 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Khlebnikov Is Everywhere! 187 Khlebnikov is Everywhere! Memoirs by Oavid Burliuk, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Amfian Reshetov, and on Osip Mandelshtam 190 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Lev Zhegin's Remembering Vasilii Chekrygin 192 Lev Zhegin Remembering Vasilii Chekrygin Part 11. -

Politics and History of 20Th Century Europe Shifted Radically, Swinging Like a Pendulum in a Dramatic Cause and Effect Relationship

Politics and history of 20th Century Europe shifted radically, swinging like a pendulum in a dramatic cause and effect relationship. I explored the correlation between art movements and revolutions, focusing specifically on Russian Constructivism and the Russian Revolution in the 1920s, as well as the Punk movement in East Germany that instigated the Fall of the Berlin Wall. I am fascinated by the structural similarities of these movements, and their shared desire of egalitarianism, which progressed with the support of opposing political ideologies. I chose fashion design because it was at the forefront of both Constructivism and Punk, and because it is what I hope to pursue as a career. After designing a full collection in 2D, I wanted to challenge myself by bringing one of my garments to life. The top is a plaster cast cut in half and shaped with epoxy and a lace up mechanism so that it can be worn. A paste made of plaster and paper pulp serves to attach the pieces of metal and create a rough texture that produces the illusion of a concrete wall. For the skirt, I created 11 spheres of various sizes by layering and stitching together different shades of white, cream, off-white, grey, and beige colored fabrics, with barbed wire and hardware cloth, that I then stuffed with Polyfil. The piece is wearable, and meant to constrict one’s freedom of movement - just like the German Democratic Party constricted freedom of speech in East Germany. The bottom portion is meant to suffocate the body in a different approach, with huge, outlandish, forms like the ones admired by the Constructivists. -

Read Book Kazimir Malevich

KAZIMIR MALEVICH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Achim Borchardt-Hume | 264 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849761468 | English | London, United Kingdom Kazimir Malevich PDF Book From the beginning of the s, modern art was falling out of favor with the new government of Joseph Stalin. Red Cavalry Riding. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The movement did have a handful of supporters amongst the Russian avant garde but it was dwarfed by its sibling constructivism whose manifesto harmonized better with the ideological sentiments of the revolutionary communist government during the early days of Soviet Union. What's more, as the writers and abstract pundits were occupied with what constituted writing, Malevich came to be interested by the quest for workmanship's barest basics. Black Square. Woman Torso. The painting's quality has degraded considerably since it was drawn. Guggenheim —an early and passionate collector of the Russian avant-garde—was inspired by the same aesthetic ideals and spiritual quest that exemplified Malevich's art. Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Use dmy dates from May All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from June Lyubov Popova - You might like Left Right. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: "In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception Retrieved 6 July A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. It was one of the most radical improvements in dynamic workmanship. Landscape with a White House. -

Vkhutemas Training Anna Bokov Vkhutemas Training Pavilion of the Russian Federation at the 14Th International Architecture Exhibition La Biennale Di Venezia

Pavilion of the Russian Federation at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition la Biennale di Venezia VKhUTEMAS Training Anna Bokov VKhUTEMAS Training Pavilion of the Russian Federation at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition la Biennale di Venezia Curated by Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design Anton Kalgaev Brendan McGetrick Daria Paramonova Comissioner Semyon Mikhailovsky Text and Design Anna Bokov With Special Thanks to Sofia & Andrey Bokov Katerina Clark Jean-Louis Cohen Kurt W. Forster Kenneth Frampton Harvard Graduate School of Design Selim O. Khan-Magomedov Moscow Architectural Institute MARCHI Diploma Studios Moscow Schusev Museum of Architecture Eeva-Liisa Pelknonen Alexander G. Rappaport Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design Larisa I. Veen Yury P. Volchok Yale School of Architecture VKhUTEMAS Training VKhUTEMAS, an acronym for Vysshie Khudozhestvenno Tekhnicheskie Masterskie, translated as Higher Artistic and Technical Studios, was conceived explicitly as “a specialized educational institution for ad- vanced artistic and technical training, created to produce highly quali- fied artist-practitioners for modern industry, as well as instructors and directors of professional and technical education” (Vladimir Lenin, 1920). VKhUTEMAS was a synthetic interdisciplinary school consisting of both art and industrial facilities. The school was comprised of eight art and production departments - Architecture, Painting, Sculpture, Graphics, Textiles, Ceramics, Wood-, and Metalworking. The exchange -

Études Photographiques, 23 | Mai 2009 When a Photograph of Trees Is Almost Like a Crime 2

Études photographiques 23 | mai 2009 Politique des images / Illustration photographique When a Photograph of Trees Is Almost like a Crime Rodchenko, Vertov, Kalatozov Bernd Stiegler Translator: James Gussen Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/3422 ISSN: 1777-5302 Publisher Société française de photographie Printed version Date of publication: 1 May 2009 ISBN: 9782911961236 ISSN: 1270-9050 Electronic reference Bernd Stiegler, « When a Photograph of Trees Is Almost like a Crime », Études photographiques [Online], 23 | mai 2009, Online since 12 February 2014, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/3422 This text was automatically generated on 30 April 2019. Propriété intellectuelle When a Photograph of Trees Is Almost like a Crime 1 When a Photograph of Trees Is Almost like a Crime Rodchenko, Vertov, Kalatozov Bernd Stiegler Translation : James Gussen ‘Think before taking the photograph, while taking the photograph, and after taking the photograph!’1 1 In 1927, the Russian artist and photographer Alexander Rodchenko spent several days at Vladiir Mayakovsky’s dacha,2 taking, what were for him, rare trips into the countryside, and then noted in his journal: ‘In Pushkino, at the dacha, I walk around and look at nature: there’s a bush, there’s a tree, here’s a ravine, stinging nettle ... Everything’s accidental and unorganized, there’s nothing to photograph, it’s not interesting. Now the pines aren’t too bad, long, bare, almost telegraph poles.’3 2 To the city dweller Rodchenko, nature seemed to be a disorganized chaos with no artistic appeal, an informal and unstructured accumulation of thicket and undergrowth. -

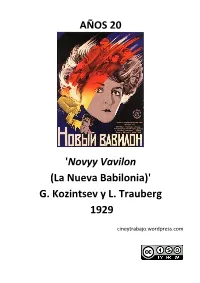

Novyy Vavilon (La Nueva Babilonia)' G

AÑOS 20 'Novyy Vavilon (La Nueva Babilonia)' G. Kozintsev y L. Trauberg 1929 cineytrabajo.wordpress.com Título original: Новый Вавилон/Novyy Vavilon; URSS, 1929; Productora: Sovkino; Director: Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg. Fotografía: Andrei Moskvin (Blanco y negro); Guión: Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg; Reparto: David Gutman, Yelena Kuzmina, Andrei Kostrichkin, Sofiya Magarill, A. Arnold, Sergei Gerasimov, Yevgeni Chervyakov, Pyotr Sobolevsky, Yanina Zhejmo, Oleg Zhakov, Vsevolod Pudovkin; Duración: 120′ “*...+¡La Comuna, exclaman, pretende abolir la propiedad, base de toda civilización! Sí, caballeros, la Comuna pretendía abolir esa propiedad de clase que convierte el trabajo de muchos en la riqueza de unos pocos. La Comuna aspiraba a la expropiación de los expropiadores.*...+” ¹ (Karl Marx) Sinopsis Ambientada en el París de 1870-1871, ‘La nueva Babilonia’ nos cuenta la historia de la instauración de la Comuna de París por parte de un grupo de hombres y mujeres que no quieren aceptar la capitulación del Gobierno de París ante Prusia en el marco de la guerra franco-prusiana. Louise, dependienta de los almacenes “La nueva Babilonia”, va a ser una de las más apasionadas defensoras de la Comuna hasta su derrocamiento en mayo de 1871. Comentario En 1929, Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg, dos de los creadores y difusores de la Fábrica del Actor Excéntrico (FEKS), escribieron y dirigieron la que se considera su obra conjunta de madurez: ‘Novyy Vavilon (La nueva Babilonia)’. Como muchas otras obras soviéticas se sirven de un hecho histórico real para exaltar la Revolución, pero la peculiaridad de la película de Trauberg y Kozintsev reside en que no sólo se remontan muchos años atrás en el tiempo, sino que además cambian de ubicación, situando la acción en la época de la guerra franco-prusiana de 1870 y la instauración de la Comuna de París al año siguiente. -

The Russian Cinematic Culture

Russian Culture Center for Democratic Culture 2012 The Russian Cinematic Culture Oksana Bulgakova Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Repository Citation Bulgakova, O. (2012). The Russian Cinematic Culture. In Dmitri N. Shalin, 1-37. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture/22 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Article in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Culture by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Russian Cinematic Culture Oksana Bulgakova The cinema has always been subject to keen scrutiny by Russia's rulers. As early as the beginning of this century Russia's last czar, Nikolai Romanov, attempted to nationalize this new and, in his view, threatening medium: "I have always insisted that these cinema-booths are dangerous institutions. Any number of bandits could commit God knows what crimes there, yet they say the people go in droves to watch all kinds of rubbish; I don't know what to do about these places." [1] The plan for a government monopoly over cinema, which would ensure control of production and consumption and thereby protect the Russian people from moral ruin, was passed along to the Duma not long before the February revolution of 1917. -

Factography Evolution from the Avant-Garde to the Absurd and Camp Prose Igor Chubarov Tyumen State University, Russia

ISPS Convention 2017 Convention 2017 “Modernization and Multiple Modernities” Volume 2018 Conference Paper Evidence and Violence: Factography Evolution from the Avant-garde to the Absurd and Camp Prose Igor Chubarov Tyumen State University, Russia Abstract This article focuses on the Russian literary avant-garde and its development in prison camp prose and documentary writing. These texts reflected an anthropological experience and response to oppression and violence in human society. In this context, it is possible to see how literature and art in general are able to change ourselves and our reality, rather than just to entertain, console and bring subjective satisfaction. Corresponding Author: The experience of alienated labor, interpreted as the experience of violence, was Igor Chubarov [email protected] expressed by avant-gardists in exaggerated imagery in their works. Therefore, I Received: 26 April 2018 propose to study the avant-garde in the context of the extreme experience of Accepted: 25 May 2018 violence, in which the political and the poetic are sometimes entwined. Published: 7 June 2018 Publishing services provided by Keywords: avant-garde, camp prose, media-aesthetic, Soviet literature, violence Knowledge E Igor Chubarov. This article is distributed under the terms of Artistic depiction of events is the author’s trial of the world around him. the Creative Commons Attribution License, which The author is omnipotent – the dead rise from their graves and live. permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the Varlam Shalamov original author and source are credited. Selection and Peer-review 1. under the responsibility of the ISPS Convention 2017 I infer the idea of Russian avant-garde based on the failure of the October Socialist Conference Committee. -

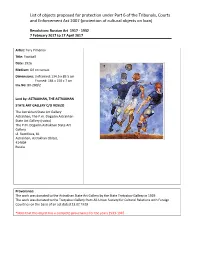

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Yury Pimenov Title: Football Date: 1926 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 134.5 x 89.5 cm Framed: 184 x 150 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/2 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery ul. Sverdlova, 81 Astrakhan, Astrakhan Oblast, 414004 Russia Provenance: The work was donated to the Astrakhan State Art Gallery by the State Tretyakov Gallery in 1929. The work was donated to the Tretyakov Gallery from All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries on the basis of an act dated 23.02.1929 *Note that this object has a complete provenance for the years 1933-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Ekaterina Zernova Title: Tomato Paste Factory Date: 1929 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 141 x 110 cm Framed: 150 x 120 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/1 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. -

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

The Cinematic Imaginary and the Photographic Fact: Media As Models for 20Th Century Art

No 29|2018 € 18,00 PhotoResearcher ESHPh European Society for the History of Photography Photography & Film Guest Editor: Martin Reinhart 7 Noam M. Elcott The Cinematic Imaginary and the Photographic Face: Media as Models for 20th Century Art 24 Katja Müller-Helle Black Box Photography 34 Roland Fischer-Briand Under A Certain Influence 48 Brian Pritchard Sensitive Strips 62 Lydia Nsiah Photofilmic Time Machines 74 Barnaby Dicker Stroboscopic Revelations in Blade Runner The Cinematic Imaginary and the Photographic Fact: Media as Models for 20th Century Art Noam M. Elcott I. Dominant Art Forms, Artistic Confusion Laocoön was in the air (fig. ).1 Irving Babbitt had revisited Lessing’s 1766 text and introduced a New Laocoön in an eponymous book published 1910.1 Not satisfied with Babbitt’s history, the critic Clement Greenberg endeavored to advance toward a newer Laocoön in a landmark essay published in 1940. He was unaware, it seems, that two years prior Rudolf Arnheim had published his own “New Laocoön” on “Artistic Composites and the Talking Film.”2 Whatever their difference—and they are by no means inconsequential—Lessing, Babbitt, Arnheim, and Greenberg were animated by a common animus: the hatred of confusion. Babbitt’s book was subtitled “An Essay on the Confusion of the Arts.” And Greenberg, famously, championed Modernism as a purification of painting from the redoubled confusion of illusionism and literature. He boasted: “The arts, then, have been hunted back to their mediums, and there Figure 1 3 William Henry Fox Talbot, Statuette of they have been isolated, concentrated and defined.” Nearly eighty years on, we can declare ‘Laocoön and his Sons’, 1845, salted-paper with confidence that the hunt is over and the prey are not only isolated, concentrated and print and calotype negative, 8.9x9.5 cm. -

Soviet Jews in World War II Fighting, Witnessing, Remembering Borderlines: Russian and East-European Studies

SOVIET JEWS IN WORLD WAR II Fighting, Witnessing, RemembeRing Borderlines: Russian and East-European Studies Series Editor – Maxim Shrayer (Boston College) SOVIET JEWS IN WORLD WAR II Fighting, Witnessing, RemembeRing Edited by haRRiet muRav and gennady estRaikh Boston 2014 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2014 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-313-9 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-61811-314-6 (electronic) ISBN 978-1-61811-391-7 (paperback) Cover design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2014 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www. academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Table of Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................