MHI-06 Evolution of Social Structures in India Through the Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application No First Name Last Name Dob Domicile

ONLINE DOMICILE_ HSE_PE ONLINE HSE_50 GEND _ASS_5 MERIT_ APPLICATION_NO FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME DOB DISTRICT_ CASTE RCENTA _ASS_S _WEIGH ER 0_WEIG MARKS NAME GE CORE TAGE HTAGE 030412054771 AMIT TRIPATHI 31/07/1979 Jabalpur UR M 78.22 83 39.11 41.5 80.61 030412090866 NEERAJ KURARIYA 10/11/1988 Jabalpur UR M 84.22 76 42.11 38 80.11 030412050851 AMIT KURARIA 18/07/1979 Jabalpur UR M 73.78 85 36.89 42.5 79.39 030412033902 NITESH YADAV 20/04/1990 Jabalpur OBC M 75.78 79 37.89 39.5 77.39 030412003591 PIYUSH KANT VISHWAKARMA 17/06/1987 Jabalpur OBC M 85.11 67 42.56 33.5 76.06 030412017892 SHALINI SONI 21/07/1989 Jabalpur OBC F 79.78 72 39.89 36 75.89 030412067488 RUCHI KOSHTA 25/05/1988 Jabalpur OBC F 87.78 62 43.89 31 74.89 030412004013 PRABHAT PAROHA 01/08/1987 Jabalpur UR M 83.33 66 41.67 33 74.67 030412042225 SUDHANSU KUMAR 17/06/1989 Jabalpur UR M 77.11 72 38.56 36 74.56 030412077856 AARTI AGRAWAL 21/10/1989 Jabalpur UR F 90.67 58 45.34 29 74.34 030412074769 AJEET SINGH RAGHUWANSHI 01/07/1989 Jabalpur UR M 82.67 65 41.34 32.5 73.84 030412104573 POOJA AHUJA 09/05/1988 Jabalpur UR F 80.67 66 40.34 33 73.34 030412060585 UPENDRA MISHRA 10/03/1987 Jabalpur UR M 78.44 68 39.22 34 73.22 030412073393 ASHUTOSH MOGHE 28/10/1979 Jabalpur UR M 78.22 68 39.11 34 73.11 030412060496 SWATI AGRAHARI 06/08/1989 Jabalpur UR F 86 60 43 30 73 030412064398 MANISH KUMAR RAI 20/10/1986 Jabalpur OBC M 78.89 67 39.45 33.5 72.95 030412082906 ASHISH KUMAR JAIN 12/03/1986 Jabalpur UR M 86.67 59 43.34 29.5 72.84 030412084151 RATAN CHAKRAWARTI 28/04/1988 Jabalpur OBC M -

The World of Labour in Mughal India (C.1500–1750)

IRSH 56 (2011), Special Issue, pp. 245–261 doi:10.1017/S0020859011000526 r 2011 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis The World of Labour in Mughal India (c.1500–1750) S HIREEN M OOSVI Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: This article addresses two separate but interlinked questions relating to India in Mughal times (sixteenth to early eighteenth century). First, the terms on which labour was rendered, taking perfect market conditions as standard; and, second, the perceptions of labour held by the higher classes and the labourers themselves. As to forms of labour, one may well describe conditions as those of an imperfect market. Slave labour was restricted largely to domestic service. Rural wage rates were depressed owing to the caste system and the ‘‘village community’’ mechanism. In the city, the monopoly of resources by the ruling class necessarily depressed wages through the market mechanism itself. While theories of hierarchy were dominant, there are indications sometimes of a tolerant attitude towards manual labour and the labouring poor among the dominant classes. What seems most striking is the defiant assertion of their status in relation to God and society made on behalf of peasants and workers in northern India in certain religious cults in the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries. The study of the labour history of pre-colonial India is still in its infancy. This is due partly to the fact that in many respects the evidence is scanty when compared with what is available for Europe and China in the same period. -

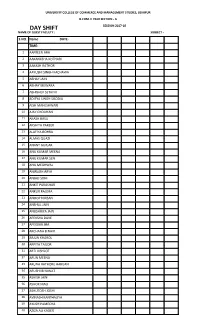

Day Shift Session 2017-18 Name of Guest Faculty : Subject - S.No

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. II YEAR SECTION - A DAY SHIFT SESSION 2017-18 NAME OF GUEST FACULTY : SUBJECT - S.NO. Name DATE- TIME- 1 AAFREEN ARA 2 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI 3 AAKASH RATHOR 4 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA 5 ABHAY JAIN 6 ABHAY MEWARA 7 ABHISHEK SETHIYA 8 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA 9 AISH MAHESHWARI 10 AJAY CHOUHAN 11 AKASH BASU 12 AKSHITA PAREEK 13 ALAFIYA BOHRA 14 ALMAS QUAZI 15 ANANT GURJAR 16 ANIL KUMAR MEENA 17 ANIL KUMAR SEN 18 ANIL MEGHWAL 19 ANIRUDH ARYA 20 ANJALI SONI 21 ANKIT PARASHAR 22 ANKUR RAJORA 23 ANOOP NIRBAN 24 ANSHUL JAIN 25 ANUSHRIYA JAIN 26 APEKSHA DAVE 27 APEKSHA JHA 28 ARCHANA B NAIR 29 ARJUN KHAROL 30 ARPITA TAILOR 31 ARTI VISHLOT 32 ARUN MEENA 33 ARUNA RATHORE HARIJAN 34 ARUSHI BIYAWAT 35 ASHISH JAIN 36 ASHOK MALI 37 ASHUTOSH JOSHI 38 AVINASH KANTHALIYA 39 AYUSH PAMECHA 40 AZIZA ALI KADER 41 BATUL 42 BHARAT LOHAR 43 BHARAT MEENA 44 BHARAT PURI GOSWAMI 45 BHAVIN JAIN 46 BHAWANA SOLANKI 47 BHUMIKA JAIN 48 BHUMIKA PALIYA 49 BHUMIT SEVAK 50 BHUPENDRA JAIN 51 BINISH KHAN 52 BURHANUDDIN MOOMIN 53 CHANCHAL SOLANKI 54 CHETAN KOTIA 55 DAKSH VYAS 56 DANISH KHAN 57 DARSHIT DOSHI 58 DEEPAK NAGDA 59 DEEPAK SHRIMALI 60 DEEPIKA SAHU 61 DEEPIKA SINGH KHARWAR 62 DEEPIKA YADAV 63 DEEPTI KUMAWAT 64 DHRUVIT KUMAWAT 65 DIKSHANT VAIRAGI 66 DINESH KUMAR MEENA 67 DINESH NAGDA 68 DINESH RAJPUROHIT 69 DIPESH JAIN 70 DIVYA GUPTA 71 DIVYA JAIN 72 DIVYA MALI 73 DIVYA NAKWAL 74 DIVYA SONI 75 DURGA BHATT 76 DURGA SHANKAR MALI 77 FATEMA BOHRA 78 FIRDOSH MANSURI 79 GAJENDRA MENARIA 80 GAJENDRA PUSHKARNA Signature of Guest Faculty DEAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. -

A/HRC/10/12/Add.1 4 March 2009

ADVANCE UNEDITED VERSION Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/10/12/Add.1 4 March 2009 ENGLISH/FRENCH/SPANISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Tenth session Agenda item 3 Report submitted by the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Margaret Sekaggya Addendum ∗ Summary of cases transmitted to Governments and replies received ∗ The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only, as it greatly exceeds the word limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. A/HRC/10/12/Add.1 Page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction............................................................. 1-3 4 Afghanistan............................................................. 4-7 4 Algeria..................................................................... 8-33 5 Angola..................................................................... 34-44 10 Argentina................................................................. 45-107 13 Armenia................................................................... 108-122 24 Azerbaijan............................................................... 123-140 27 Bahamas.................................................................. 141-148 30 Bahrain.................................................................... 149- 224 32 Belarus .................................................................... 225-265 49 Bolivia..................................................................... 266-269 57 Bosnia and Herzegovina ......................................... 270-280 -

University College of Commerce & Management

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE & MANAGEMENT STUDIES MOHANLAL SUKHADIA UNIVERSITY, UDAIPUR. ELECTORAL LIST- 2016-17 B.COM. FIRST YEAR S. No. Name of Applicant Father Name ADDRESS 1 AAFREEN ARA ASHFAQ AHMED 113 nag marg outside chandpol 2 AAFREEN SHEIKH SHAFIQ AHMED SHEIKH 51 RAJA NAGAR SEC 12 SAVINA 3 AAISHA SIDDIKA MR.ABDUL HAMEED NAYA BAJAR KANORE THE-VALLABHNAGER DIS-UDAIPUR 4 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI PRAVEEN KUMAR KOTHARI 5, KANJI KA HATTA, GALI NO.1, OPP. SH DIG JAIN SCHOOL 5 AAKASH RATHOR ROSHAN LAL RATHOR 17 RAMDAWARA CHOWK BHUPALWARI UDAIPUR 6 AANCHAL ASHOK JAIN 61, A - BLOCK, HIRAN MAGRI SEC-14, UDAIPUR 7 AASHISH PATIDAR KAILASH PATIDAR VILL- DABOK 8 AASHRI KHATOD ANIL KHATOD 340,BASANT VIHAR,HIRAN MAGRI,SEC-5 9 AAYUSHI BANSAL UMESH BANSAL 4/543 RHB COLONY GOVERDHAN VILAS SEC. 14 UDAIPUR 10 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA SHAKTI SINGH KACHAWA 1935/07 NEW RAMPURA COLONY SISARMA ROAD 11 ABHAY JAIN PRADEEP JAIN 18, GANESH GHATI, 12 ABHAY MEWARA SUBHASH CHANDRA MEWARA 874, MANDAKINIMARG BIJOLIYA 13 ABHISHEK DHABAI HEMANT DHABAI 209 OPP D E O SECOND GOVERDHAN VILLAS UDAIPUR 14 ABHISHEK JAIN PADAM JAIN HOUSE NO 632 SINGLE STORIE SEC 9 SAVINA 15 ABHISHEK KUMAR SINGH KHOOB SINGH 1/26 R.H.B. colony,Goverdhan Vilas,Udaipur(Raj.) 16 ABHISHEK PALIWAL KISHOR KALALI MOHALLA, CHHOTI SADRI 17 ABHISHEK SANADHYA DHAREMENDRA SANADHYA 47 ANAND VIHAR ROAD NO 2 TEKRI 18 ABHISHEK SETHIYA GOPAL LAL SETHIYA SADAR BAZAR RAILMAGRA 19 ABHISHEK SINGH RAO NARSINGH RAO 32-VIJAY SINGH PATHIK NAGAR SAVINA Page 1 of 186 20 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA BHARAT SINGH SISODIA 39, CHINTA MANI -

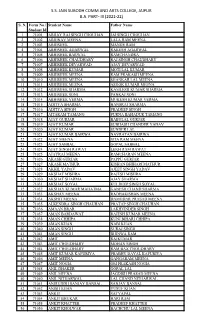

Ss Jain Subodh Comm and Arts College, Jaipur Ba Part

S.S. JAIN SUBODH COMM AND ARTS COLLEGE, JAIPUR B.A. PART- III (2021-22) S. N. Form No./ Student Name Father Name Student Id 1 71001 ABHAY RAJ SINGH CHOUHAN JAI SINGH CHOUHAN 2 71002 ABHINAV MEENA LALA RAM MEENA 3 71003 ABHISHEK MANGE RAM 4 71004 ABHISHEK AGARWAL RAKESH AGARWAL 5 71005 ABHISHEK BARWAL RAMCHANDRA 6 71006 ABHISHEK CHAUDHARY RAJ SINGH CHAUDHARY 7 71007 ABHISHEK DEVARWAD AJAY DEVARWAD 8 71008 ABHISHEK KUMAR MOTI LAL KUMAR 9 71009 ABHISHEK MEENA RAM PRAKASH MEENA 10 71010 ABHISHEK MEENA SHANKAR LAL MEENA 11 71011 ABHISHEK MEENA ASHOK KUMAR MEENA 12 71012 ABHISHEK SHARMA KAMLESH KUMAR SHARMA 13 71013 ABHISHEK SONI PANKAJ SONI 14 71014 ABHISHEK VERMA MUKESH KUMAR VERMA 15 71015 ADITYA SHARMA HANSRAJ SHARMA 16 71016 ADITYA SINGH PRADEEP SINGH 17 71017 AITARAM TAMANG PURNA BAHADUR TAMANG 18 71018 AJAY GURJAR BABULAL GURJAR 19 71019 AJAY KUMAR SUBHASH CHANDER YADAV 20 71020 AJAY KUMAR SUNDER LAL 21 71021 AJAY KUMAR BAIRWA NAVRATAN BAIRWA 22 71022 AJAY MEENA SITA RAM MEENA 23 71023 AJAY SABBAL GOPAL SABBAL 24 71024 AJAY SINGH RAWAT LEKH RAM RAWAT 25 71025 AJAYRAJ MEENA RAMCHARAN MEENA 26 71026 AKASH GURJAR PAPPU GURJAR 27 71027 AKASH MATHUR KISHAN BHIHARI MATHUR 28 71028 AKHIL YADAV AJEET SINGH YADAV 29 71029 AKSHAT MISHRA RAJESH MISHRA 30 71030 AKSHAT SHARMA AJAY SHARMA 31 71031 AKSHAT SOYAL KULDEEP SINGH SOYAL 32 71032 AKSHAY KUMAR MAHATMA GANESH CHAND SHARMA 33 71033 AKSHAY MEENA RADHAKISHAN MEENA 34 71034 AKSHIT MEENA DAMODAR PRASAD MEENA 35 71035 ALKENDRA SINGH CHAUHAN PRATAP SINGH CHAUHAN 36 71036 AMAAN BRAR LAKHVINDER SINGH -

Sun Worship in Himalaya Region: with Special Reference to Katarmal and Martand

Artistic Narration: A Peer Reviewed Journal of Visual & Performing Art ISSN (P): 0976-7444 Vol. IV., 2013 Sun Worship in Himalaya Region: with Special Reference to Katarmal and Martand Dr. Virendra Bangroo Assistant Professor IGNCA, New Delhi. & Dr. Richan Kamboj Assistant Professor & HOD, Department of Drawing & Painting M.K.P.(P.G.) College Dehra Dun. The Sun, the source of light and solar energy, is the sources of all life and finds mention in all the sacred texts like the Rig Veda, the Vishnu Purana, the Mahabharta, the Bhavisya Purana, the Chandogya Upanishad, the Markandaya Purana, the Taittiriya Upansihad, the Nilarudra Upanishad and the Varaha purana. The Sun or Surya is also known by other names, each name highlights the grandeur, brilliance, quality and power of the Sun,viz:- 1. Aditya- Son of the primordial vastness ss 2. Aja-ekapad – one legged goat 3. Pavaka – Purifier 4. Jivana- the source of life 5. Jayanta-Victorious 6. Ravi - Divider 7. Martanda- born from life less egg 8. Savitr -Nourisher 9. Aharpati-Lord of the day 10. Jagat chaksu-Eye of the world 11 - Karma Sanskasin -Witness of deeds 12. Graha Rajan-King of Planets 13. Sahasra-Kirana-Having Thousand beams 14. Saptashwa-Having seven horses 15. Dyumani-Gem of the sky 1 Artistic Narration: A Peer Reviewed Journal of Visual & Performing Art ISSN (P): 0976-7444 Vol. IV., 2013 16. Graha pati-Lord of the Planets 17. Heli-Pervader 18. Khaga-Wanderer of space 19. Padma-bandhu-Friend of the lotus 20. Padma Pani-Lotus in hand 21. Himarati- Enemy of snow 22. -

A/HRC/WGEID/118/1 Advance Edited Version

A/HRC/WGEID/118/1 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 30 July 2019 Original: English Human Rights Council Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances Communications transmitted, cases examined, observations made and other activities conducted by the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances* 118th session (13–22 May 2019) I. Communications 1. Between its 117th and 118th sessions, the Working Group transmitted 50 cases under its urgent action procedure, to: Bangladesh (3), Burundi (3), Egypt (19), India (1), Libya (1), Pakistan (11), Russian Federation (1), Saudi Arabia (1), Sudan (1), Syrian Arab Republic (2), Turkey (6) and Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) (1). 2. At its 118th session, the Working Group decided to transmit 172 newly reported cases of enforced disappearance to 19 States: Algeria (5), Burundi (31), Cameroon (1), China (20), Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (14), Egypt (2), Eritrea (1), India (17), Iran (Islamic Republic of) (4), Libya (2), Mexico (2), Pakistan (12), Republic of Korea (1), Saudi Arabia (2), Sri Lanka (45), Syrian Arab Republic (10), Tunisia (1) United Arab Emirates (1) and Yemen (1). 3. The Working Group clarified 62 cases, in: Azerbaijan (1), Bangladesh (2), China (1), Egypt (39), Morocco (4), Nigeria (2), Pakistan (3), Saudi Arabia (3), Syrian Arab Republic (1), Thailand (1) Turkey (4) and Ukraine (1). A total of 50 cases were clarified on the basis of information provided by the Governments and 12 on the basis of information provided by sources. 4. Between its 117th -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

1 Do Not Reproduce This Article in Part Or Full Without Written Permission of Author How the British Divided Punjab Into Hindu

How the British divided Punjab into Hindu and Sikh By Sanjeev Nayyar December 2016 This is chapter 2 from the E book on Khalistan Movement published by www.swarajyamag.com During a 2012 visit to Naina Devi Temple in Himachal Pradesh, about an hour's drive from Anandpur Sahib, I wondered why so many Sikhs come to the temple for darshan. The answer lies in the events of 1699. In the Chandi Charitra, the tenth Guru says that in the past god had deputed Goddess Durga to destroy evil doers. That duty was now assigned to him hence he wanted her blessings. So he invited Pandit Kesho from Kashi to conduct the ceremony at the hill of Naina Devi. The ceremony started on Durga Ashtami day, in the autumn of October 1698, and lasted for six months. At the end of this period, the sacred spring Navratras began on 21 March 1699. Then, “When all the ghee and incense had been burnt and the goddess had yet not appeared, the Guru came forward with a naked sword and, flashing it before the assembly declared: ‘This is the goddess of power!” This took place on 28 March 1699, the Durga Ashtami day. The congregation was then asked to move to Anandpur, where on New Year Day of 1st Baisakh, 1699, the Guru would create a new nation.” 3 On 30 March 1699, at Anandpur, Govind Singhji gave a stirring speech to the assembly about the need to protect their spiritual and temporal rights. He then asked if anyone would offer his head in the services of God, Truth and Religion. -

Baroda, Imperial Tables, Part II, Vol-XVI-A

CENSUS OF INDIA, 19II. VOLUME XVI-A. ... - BARODA STATE. 1.' PART II. THE IMPERIAL TABLES BY OOVIN 0 BHAI H. DESAI, B.A., LL. B., SUPE~INTBNDENT OF CENSUS OPE~TIONS, BARODA STATE. PRINTED AT THE TIMES PRESS. 191 J. Price-Indian, Os. 3; Ellglish, 'Is. TABLE OF CON'rENTS. PAGlI. TABLE I-AREA, Hou8ES AND POI'ULA'l'IO"" • ••• 1 VABIA'l.'IO~ IN POPULA'l'ION ~~E ~ iii: ......- .. .,' _ " Il- 1872 ". .... 3 III-ToWNS AND VILJ.AGES GI,AS.. rfED BY POPULATION -:: .... r~~ ••• 7 " •••• 40 0 ' . of , .. IV-ToWNIi OLASSI!i'IED NY PnI'UI'A'tiq~, #iTH' .vAW7'iON, surOB 1872 ••• 9 " o 'Ii.... •. I· ....... V-TowNs ABRANGFJD TgnmTORIALLY ;;ifir FOPu1.iATi:~ BY RBLIOION ••• 13 " VI-RELIGION " 00. 17 VII-A(m, SEX AND OIVII. ()ONDITION- " Part A-Provincial Smumllry 20 .. l1-Details for Districts 24 C-Detail,; for the City of Baroda 38 " VllI-EDUCATION BY HELIGION AND AGE- Part ... I-Provincial Summary 38 ., B-Detnils for Districts .. ... ... 39 C-Details for tlw City of Bnroda 42 " IX-EDUCA'l'ION BY SElEOTED C:As'rES, TRIBES OR RAOE!! 43 " X-LANGUAGE 47 " ... XI-BIRT1{~PLACE 53 " ... XII-h~'IR)IITmS- " Part I-Di~h'ihntion by Age ... 64 ,. II-Distrihution by District~ 64: " XIIA-bFIllMI'rIES BY f;ELJoJGTED CASTES, TRlBES on RAOES 65 " XIII-CAS'I'E, TRIBE, RAOE OR ~ATlONAMTY- Pl.ut A-Hindu:;, ,Jains, Animists and Arya Samajists 70 ' " B-}!u~hnan~ 00. -80 XIV-CIVIL CONDITION BY Am;: FOR KELEO'l'ED CASTES 83 " XV-OCOUPATION OR }!EAXS OF IJIVIiLIHoon !n " Part A-Heneml Tahle 92 " B-Hl1bsidillry Occupations of' Agricultul'ists- Actnal Workers only (1) Hent Receivers . -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita