Articulating Desire Leonie Watson University of Wollongong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equipo Crónica

Equipo Crónica Tomàs Llorens 1 This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao © Equipo Crónica (Manuel Valdés), VEGAP, Bilbao, 2015 Photography credits © Archivo Fotográfico Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Alicante, MACA: fig. 9 © Archivo Fotográfico Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía: figs. 11, 12 © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa-Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 15, 20 © Colección Arango: fig. 18 © Colección Guillermo Caballero de Luján: figs. 4, 7, 10, 16 © Fundación “la Caixa”. Gasull fotografía: fig. 8 © Patrimonio histórico-artístico del Senado: fig. 19 © Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast - ARTOTHEK: fig. 14 Original text published in the catalogue Equipo Crónica held at the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (10 February to 18 May 2015). Sponsored by: 2 1 Estampa Popular de Valencia and the beginnings of Equipo Crónica Founded in 1964, Equipo Crónica and Estampa Popular de Valencia presented themselves to the public as two branches of a single project. Essentially, however, they were two different, independent ones and either could have appeared and evolved without the other. -

Spanish Art (From the Baroque to the Present Day)

Centro de Lenguas Modernas – Universidad de Granada - Syllabus Hispanic Studies Course SPANISH ART (FROM THE BAROQUE TO THE PRESENT DAY) General description The course is a synthesis to consider only the essential aspects of Spanish art from the Baroque to the present-day. The classes will feature the necessary means of audiovisual aids, slides, videos, etc so that the student will identify the works of art and their environment. Granada, a city of great artistic wealth, enables the students also to visit monuments for first-hand knowledge of works of art which are fundamental to the evolution of Spanish art. The artistic preparation of the students can be enriched and completed with trips to nearby Andalusian cities: Seville, Córdoba, which are also outstanding in the wealth of their artistic heritage. Furthermore, students are recommended to visit other cities –farther away – however, especially significant because of their artistic value or the importance of their museums; Madrid, Barcelona, Toledo, Ávila, Salamanca or Santiago de Compostela, amongst others. Syllabus content 1.- Concept and meaning of Baroque. 2.- Fundamental aspects of Baroque architecture: 2.1. From the origins to the affirmation of the style. 2.2. Ornamental Baroque architecture. 2.3. Borbonic Baroque architecture. 3.- Great masters of Spanish Baroque sculpture: 3.1. Castillian school: Gregorio Fernández. 3.2. Andalusian school: Sevilla: Juan Martínez Montañés, Juan Mesa, Pedro Roldán. Granada: Alonso Cano, Pedro de Mena, José de Mora. 3.3. Levantine school: Francisco Salcillo. 4.- Spanish Baroque painting: 4.1. The great master: Velásquez. Juventud en Sevilla y triunfo en la corte de Felipe IV. -

The Symbolism of Blood in Two Masterpieces of the Early Italian Baroque Art

The Symbolism of blood in two masterpieces of the early Italian Baroque art Angelo Lo Conte Throughout history, blood has been associated with countless meanings, encompassing life and death, power and pride, love and hate, fear and sacrifice. In the early Baroque, thanks to the realistic mi of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, blood was transformed into a new medium, whose powerful symbolism demolished the conformed traditions of Mannerism, leading art into a new expressive era. Bearer of macabre premonitions, blood is the exclamation mark in two of the most outstanding masterpieces of the early Italian Seicento: Caravaggio's Beheading a/the Baptist (1608)' (fig. 1) and Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Halo/ernes (1611-12)2 (fig. 2), in which two emblematic events of the Christian tradition are interpreted as a representation of personal memories and fears, generating a powerful spiral of emotions which constantly swirls between fiction and reality. Through this paper I propose that both Caravaggio and Aliemisia adopted blood as a symbolic representation of their own life-stories, understanding it as a vehicle to express intense emotions of fear and revenge. Seen under this perspective, the red fluid results as a powerful and dramatic weapon used to shock the viewer and, at the same time, express an intimate and anguished condition of pain. This so-called Caravaggio, The Beheading of the Baptist, 1608, Co-Cathedral of Saint John, Oratory of Saint John, Valletta, Malta. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Halafernes, 1612-13, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. llO Angelo La Conte 'terrible naturalism'3 symbolically demarks the transition from late Mannerism to early Baroque, introducing art to a new era in which emotions and illusion prevail on rigid and controlled representation. -

Ribera's Drunken Silenusand Saint Jerome

99 NAPLES IN FLESH AND BONES: RIBERA’S DRUNKEN SILENUS AND SAINT JEROME Edward Payne Abstract Jusepe de Ribera did not begin to sign his paintings consistently until 1626, the year in which he executed two monumental works: the Drunken Silenus and Saint Jerome and the Angel of Judgement (Museo di Capodimonte, Naples). Both paintings include elaborate Latin inscriptions stating that they were executed in Naples, the city in which the artist had resided for the past decade and where he ultimately remained for the rest of his life. Taking each in turn, this essay explores the nature and implications of these inscriptions, and offers new interpretations of the paintings. I argue that these complex representations of mythological and religious subjects – that were destined, respectively, for a private collection and a Neapolitan church – may be read as incarnations of the city of Naples. Naming the paintings’ place of production and the artist’s city of residence in the signature formulae was thus not coincidental or marginal, but rather indicative of Ribera inscribing himself textually, pictorially and corporeally in the fabric of the city. Keywords: allegory, inscription, Naples, realism, Jusepe de Ribera, Saint Jerome, satire, senses, Silenus Full text: http://openartsjournal.org/issue-6/article-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5456/issn.2050-3679/2018w05 Biographical note Edward Payne is Head Curator of Spanish Art at The Auckland Project and an Honorary Fellow at Durham University. He previously served as the inaugural Meadows/Mellon/Prado Curatorial Fellow at the Meadows Museum (2014–16) and as the Moore Curatorial Fellow in Drawings and Prints at the Morgan Library & Museum (2012–14). -

Winter Dialogue-Final-2

Docent Council Dialogue Winter 2013 Published by the Docent Council Volume XLIIl No 2 From Ethereal to Earthy The Legacy of Caravaggio 1 Inside the Dialogue Reflections on a Snowy Morning.......................Diane Macris, President, Docent Council Page 3 Winter Message..................................................Charlene Shang Miller, Docent and Tour Programs Manager Page 3 A Docent’s Appreciation of Alona Wilson........................................................JoAn Hagan, Docent Page 4 An Idea whose Time had Come................................Sandy Voice Page 5 Presentations:Works of Art from Burst of Light ......Docent Contributors Pages 7-20 The Transformative Genius of Caravaggio...............JoAn Hagan Page10 Flicks: The Dialogue Goes to the Cinema....................................................Sandy Voice Page 10 A Docent’s Guide to the Saints..................................Beth Malley Page 11 From the Sublime to the Ridiculous and Back..........Hope Vath Page 13 The Bookshelf: A Book Review.................................BethMalley Page 15 A Passion for Stickley ...............................................Laura Harris Page 20 From the Collection of Stephen Gray Docent Council Dialogue The Dialogue is created by and for docents and provides a forum for touring ideas and techniques, publishing information that is vital to docent interests such as museum changes, and recording docent activities and events. The newsletter is published in Fall, Winter, and Spring editions. Editorial Staff Sandy Voice Co-Editor -

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI E Il Suo Tempo

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI e il suo tempo Attraverso un arco temporale che va dal 1593 al 1653, questo volume svela gli aspetti più autentici di Artemisia Gentileschi, pittrice di raro talento e straordinaria personalità artistica. Trenta opere autografe – tra cui magnifici capolavori come l’Autoritratto come suonatrice di liuto del Wadsworth Atheneum di Hartford, la Giuditta decapita Oloferne del Museo di Capodimonte e l’Ester e As- suero del Metropolitan Museum di New York – offrono un’indagine sulla sua carriera e sulla sua progressiva ascesa che la vide affermarsi a Firenze (dal 1613 al 1620), Roma (dal 1620 al 1626), Venezia (dalla fine del 1626 al 1630) e, infine, a Napoli, dove visse fino alla morte. Per capire il ruolo di Artemisia Gentileschi nel panorama del Seicento, le sue opere sono messe a confronto con quelle di altri grandi protagonisti della sua epoca, come Cristofano Allori, Simon Vouet, Giovanni Baglione, Antiveduto Gramatica e Jusepe de Ribera. e il suo tempo Skira € 38,00 Artemisia Gentileschi e il suo tempo Roma, Palazzo Braschi 30 novembre 2016 - 7 maggio 2017 In copertina Artemisia Gentileschi, Giuditta che decapita Oloferne, 1620-1621 circa Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi, inv. 1597 Virginia Raggi Direzione Musei, Presidente e Capo Ufficio Stampa Albino Ruberti (cat. 28) Sindaca Ville e Parchi storici Amministratore Adele Della Sala Amministratore Delegato Claudio Parisi Presicce, Iole Siena Luca Bergamo Ufficio Stampa Roberta Biglino Art Director Direttore Marcello Francone Assessore alla Crescita -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

Caravaggio's Narcissus at the Source (Accompanied with Flash Video)

Caravaggio's Narcissus at the Source (accompanied with flash video) Ovid, Metamorphoses, c. 8 C.E. translation from Latin by Sir Samuel Garth, John Dryden, et.al. There stands a fountain in a darksom wood, Nor stain'd with falling leaves nor rising mud; Untroubled by the breath of winds it rests, Unsully'd by the touch of men or beasts; High bow'rs of shady trees above it grow, And rising grass and chearful greens below. Pleas'd with the form and coolness of the place, And over-heated by the morning chace, Narcissus on the grassie verdure lyes: But whilst within the chrystal fount he tries To quench his heat, he feels new heats arise. For as his own bright image he survey'd, He fell in love with the fantastick shade; And o'er the fair resemblance hung unmov'd, Nor knew, fond youth! it was himself he lov'd. The well-turn'd neck and shoulders he descries, The spacious forehead, and the sparkling eyes; The hands that Bacchus might not scorn to show, And hair that round Apollo's head might flow; With all the purple youthfulness of face, That gently blushes in the wat'ry glass. By his own flames consum'd the lover lyes, And gives himself the wound by which he dies. To the cold water oft he joins his lips, Oft catching at the beauteous shade he dips His arms, as often from himself he slips. Nor knows he who it is his arms pursue With eager clasps, but loves he knows not who. -

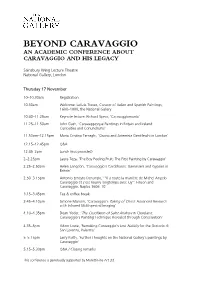

Programme for Beyond Caravaggio

BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre National Gallery, London Thursday 17 November 10–10.30am Registration 10.30am Welcome: Letizia Treves, Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings, 1600–1800, the National Gallery 10.40–11.25am Keynote lecture: Richard Spear, ‘Caravaggiomania’ 11.25–11.50am John Gash, ‘Caravaggesque Paintings in Britain and Ireland: Curiosities and Conundrums’ 11.50am–12.15pm Maria Cristina Terzaghi, ‘Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in London’ 12.15–12.45pm Q&A 12.45–2pm Lunch (not provided) 2–2.25pm Laura Teza, ‘The Boy Peeling Fruit: The First Painting by Caravaggio’ 2.25–2.50pm Helen Langdon, ‘Caravaggio's Cardsharps: Gamesters and Gypsies in Britain’ 2.50–3.15pm Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, ‘“Il a toute la manière de Michel Angelo Caravaggio et s'est nourry longtemps avec luy”: Finson and Caravaggio, Naples 1606–10’ 3.15–3.45pm Tea & coffee break 3.45–4.10pm Simone Mancini, ‘Caravaggio's Taking of Christ: Advanced Research with Infrared Multispectral Imaging’ 4.10–4.35pm Dean Yoder, ‘The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in Cleveland: Caravaggio’s Painting Technique Revealed through Conservation’ 4.35–5pm Adam Lowe, ‘Remaking Caravaggio’s Lost Nativity for the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, Palermo’ 5–5.15pm Larry Keith, ‘Further Thoughts on the National Gallery’s paintings by Caravaggio’ 5.15–5.30pm Q&A / Closing remarks This conference is generously supported by Moretti Fine Art Ltd. BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury -

Artemisia Gentileschi : the Heart of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-13-2010 Artemisia Gentileschi : The eH art of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar Deborah Anderson Silvers University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Silvers, Deborah Anderson, "Artemisia Gentileschi : The eH art of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3588 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Artemisia Gentileschi : The Heart of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar by Deborah Anderson Silvers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Naomi Yavneh, Ph.D. Annette Cozzi, Ph.D. Giovanna Benadusi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 13, 2010 Keywords: Baroque, Susanna and the Elders, self referential Copyright © 2010, Deborah Anderson Silvers DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to my husband, Fon Silvers. Nearly seven years ago, on my birthday, he told me to fulfill my long held dream of going back to school to complete a graduate degree. He promised to support me in every way that he possibly could, and to be my biggest cheerleader along the way. -

Mediterraneo in Chiaroscuro. Ribera, Stomer E Mattia Preti Da Malta a Roma Mostra a Cura Di Sandro Debono E Alessandro Cosma

Mediterraneo in chiaroscuro. Ribera, Stomer e Mattia Preti da Malta a Roma mostra a cura di Sandro Debono e Alessandro Cosma Roma, Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma - Palazzo Barberini 12 gennaio 2017 - 21 maggio 2017 COMUNICATO STAMPA Le Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma presentano dal 12 gennaio a 21 maggio 2017 nella sede di Palazzo Barberini Mediterraneo in chiaroscuro. Ribera, Stomer e Mattia Preti da Malta a Roma, a cura di Sandro Debono e Alessandro Cosma. La mostra raccoglie alcuni capolavori della collezione del MUŻA – Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti (Heritage Malta) de La Valletta di Malta messi a confronto per la prima volta con celebri opere della collezione romana. La mostra è il primo traguardo di una serie di collaborazioni che le Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma hanno avviato con i più importanti musei internazionali per valorizzare le rispettive collezioni e promuoverne la conoscenza e lo studio. In particolare l’attuale periodo di chiusura del museo maltese, per la realizzazione del nuovo ed innovativo progetto MUŻA (Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Museo Nazionale delle Arti), ha permesso di avviare un fruttuoso scambio che ha portato a Roma le opere in mostra, mentre approderanno sull’isola altrettanti dipinti provenienti dalle Gallerie Nazionali in occasione di una grande esposizione nell’ambito delle iniziative relative a Malta, capitale europea della cultura nel 2018. In mostra diciotto dipinti riprendono l’intensa relazione storica e artistica intercorsa tra l’Italia e Malta a partire dal Seicento, quando prima Caravaggio e poi Mattia Preti si trasferirono sull’isola come cavalieri dell’ordine di San Giovanni (Caravaggio dal 1606 al 1608, Preti per lunghissimi periodi dal 1661 e vi morì nel 1699), favorendo la progressiva apertura di Malta allo stile e alle novità del Barocco romano. -

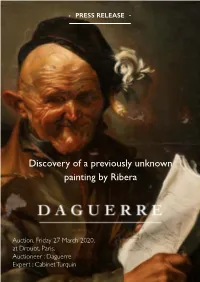

Discovery of a Previously Unknown Painting by Ribera

PRESS RELEASE Discovery of a previously unknown painting by Ribera Auction, Friday 27 March 2020, at Drouot, Paris. Auctioneer : Daguerre Expert : Cabinet Turquin Discovery of a previously unknown pain- ting by Ribera, a major 17th century artist Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) was only 20 years old when he painted this work, « The Mathematician ». The Spanish born artist was yet to achieve his renown as the great painter of Naples, the city considered to be one of the most important artistic centers of the 17th century. It is in Rome, before this Neapolitan period, in around 1610, that Ribera paints this sin- gular and striking allegory of Knowledge. The painting is unrecorded and was unknown to Ribera specialists. Now authenticated by Stéphane Pinta from the Cabinet Turquin, the work is to be sold at auction at Drouot on 27 March 2020 by the auction house Daguerre with an estimate of 200,000 to 300,000 Euros. 4 key facts to understand the painting 1. This discovery sheds new light on the artist’s early period that today lies at the heart of research being done on his oeuvre. 2. The painting portrays one of the artist’s favorite models, one that he placed in six other works from his Roman period. 3. In this painting, Ribera gives us one of his most surprising and colorful figures; revealing a sense of humor that was quite original for the time. 4. His experimenting with light and his choosing of a coarse and unfortunate sort of character to represent a savant echo both the chiaroscuro and the provocative art of Caravaggio.