Report of the National Task Force on Privacy, Technology, And…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

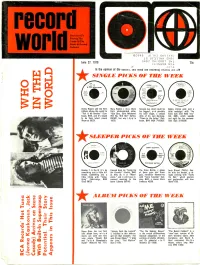

Record World

record tWODedicated To Serving The Needs Of The Music & Record Industry x09664I1Y3 ONv iS Of 311VA ZPAS 3NO2 ONI 01;01 3H1 June 21, 1970 113N8V9 NOti 75c - In the opinion of the eUILIRS,la's wee% Tne itmuwmg diCtie SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK EPIC ND ARMS CAN EVER HOLD YOU CORBYVINTON Kenny Rogers and the First Mary Hopkin sings Doris Nilsson has what could be Bobby Vinton gets justa Edition advise the world to Day'sphilosophicaloldie, his biggest, a n dpossibly littlenostalgicwith"No "TellItAll Brother" (Sun- "Que Sera, Sera (Whatever hisbest single,a unique Arms Can Ever Hold You" beam, BMI), and it's bound WillBe, WillBe)" (Artist, dittyofhis own devising, (Gil, BMI),whichsounds tobe theirlatestsmash ASCAP), her way (A p p le "Down to the Valley" (Sun- just right for the summer- (Reprise 0923). 1823). beam, BM!) (RCA 74-0362). time (Epic 5-10629). SLEEPER PICKS OF THE WEEK SORRY SUZANNE (Jan-1111 Auto uary, Embassy BMI) 4526 THE GLASS BOTTLE Booker T. & the M. G.'s do Canned Heat do "Going Up The Glass Bottle,a group JerryBlavat,Philly'sGea something just alittledif- the Country" (Metric, BMI) ofthreeguysandthree for with the Heater,isal- ferent,somethingjust a astheydo itin"Wood- gals, introduce themselves ready clicking with "Tasty littleliltingwith"Some- stock," and it will have in- with "Sorry Suzanne" (Jan- (To Me),"whichgeators thing" (Harrisongs, BMI) creasedmeaningto the uary, BMI), a rouser (Avco andgeatoretteswilllove (Stax 0073). teens (Liberty 56180). Embassy 4526). (Bond 105). ALBUM PICKS OF THE WEEK DianaRosshasherfirst "Johnny Cash the Legend" "The Me Nobody Knows" "The Naked Carmen" isa solo album here, which is tributed in this two -rec- isthe smash off-Broadway "now"-ized versionofBi- startsoutwithherfirst ord set that includes' Fol- musical adaptation of the zet's timeless opera. -

“NO MORE” Ending Sex Trafficking in Canada

“NO MORE” Ending Sex-Trafficking In Canada Report of the National Task Force on Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada commissioned by the Canadian Women’s Foundation Fall 2014 2 Report of the National Task Force on Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada “ True equality for women and girls will not be achieved until all forms of violence, including sexual exploitation and sex trafficking, are eradicated. This will require a broad perspective and action taken in all sectors and in a wide range of policy areas. The results will reflect a stronger nation whose political, social and economic inequalities are minimized and where human rights and the possibility for everyone to succeed to their greatest potential is achieved.” The Task Force on Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada Report of the National Task Force 3 on Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada This report summarizes the findings and recommendations of the Task Force on Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada. The Task Force was created and funded by the Canadian Women’s Foundation to investigate the nature and extent of sex trafficking in Canada, and to recommend a national anti-trafficking strategy to inform the work of the Canadian Women’s Foundation. The findings and recommendations contained in this report were developed to assist the Canadian Women’s Foundation in creating its own five-year national anti-trafficking strategy. It is also hoped the recommendations will inform and offer guidance to other stakeholders working in this area. The Canadian Women’s Foundation strategy to end sex trafficking is available at www.canadianwomen.org/trafficking The Canadian Women’s Foundation’s work on sex trafficking in Canada was made possible by a generous donation from the Estate of Ann Southam, a celebrated music composer and member of the Order of Canada, to support its work with women and girls in Canada. -

Joint Interagency Task Force–South: the Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success by Evan Munsing and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 5 Joint Interagency Task Force–South: The Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success by Evan Munsing and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Complex Operations, and Center for Strategic Conferencing. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by performing research and analysis, publication, conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands, to support the national strategic components of the academic programs at NDU, and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and to the broader national security community. Cover: Joint Interagency Task Force–South headquarters at Naval Air Station Key West, Florida. Photo by Linda Crippen Inset: Crossed-out snowflakes and marijuana leaves represent drug seizures. USCG (PA2 Donnie Brzuska) Joint Interagency Task Force–South: The Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success Joint Interagency Task Force–South: The Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success By Evan Munsing and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 5 Series Editor: Phillip C. Saunders National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2011 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Churches, Will Conduct I an Au Night Huddle Which Re Moscow, Aug

ij n o D A T ; A p o w r w . 19491 ' I r O U R T tE !? - i9Ianr(;>Bter lEttgttteg Ij^ralh Tba Waaibie;--i.^= Averafs Dally Nat Praaa Ron | Fanaaet «4 C. 8. WaalBl For me Moom of Soly Ittt The Pe(ll*h Women’s Amanc*, Building Inspector David Cham » - ■ Mrs. Nettla Fenton of Detroit, Group NO. 246, will hold Its bers Issued today to Contractor M r amt m Mich.. Is ^^siUng her sister. Miss monthly meeting Satur^y eve- Ray Skopek a p e ^ t for the erec 9,339 eoat tooIgM; About Town Bemioe Juul of 99 East Center ninfir at eight o’clock in the tion of a five-room, one-story, sin street. ment of the Polish-Ameripan club gle family dwrelUng for Elmer E. e « ma AalH teSayi Movii-ard W. Kwmah, «on » t Mr. on Clinton street. All members Kllbv on Lyndale street at an es A son. their first child, w m are urged to attend. timated cost of 18,000. Manehe*ter— A Ciiy of Village Charm t;.., Mrs. VV.-I. J. KwMh of 95 born yesterday In Hartford hospi- p.^jaell rflroot, Mancherter, Conn., U1 to Mr. and Mrs. Ernest Kiss- rrcently wa§ graduated from the man of 73 Curtiss street. Hart AivirtMag Oa Page X) MANCHESTER, CONN, SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, .1948 (TEN PAGES) PRICE FOUR CBNUl Mechaiuca and Maintenance coni'se ford. Prior to her marriage Mrs. VOL. LXVIL, NO. 859 of the Academy of Aeronautics. Klssman was the former Dorothy LaOuardla Airport, New York. -

On the Record: Report of the Library of Congress Working Group on The

OOnn tthhee RReeccoorrdd __________________________________________________________________________ Report of The Library of Congress Working Group on the Future of Bibliographic Control January 9, 2008 WORKING GROUP ON THE FUTURE OF BIBLIOGRAPHIC CONTROL Richard Amelung John Latham Associate Director Director, Information Center Omer Poos Law Library Special Libraries Association Saint Louis University Clifford Lynch Diane Boehr Executive Director Head, Cataloging Section Coalition for Networked Information Technical Services Division Olivia M. A. Madison (Co-Chair) National Library of Medicine Dean of the Library Diane Dates Casey Iowa State University Dean of Library Services and Judith Nadler Academic Computing Director and University Librarian Governors State University University of Chicago Library Daniel Clancy Brian E. C. Schottlaender (Co-Editor) Engineering Director The Audrey Geisel University Librarian Google University of California, San Diego Christopher Cole Sally Smith Associate Director, Technical Services Manager of Cataloging and Processing National Agricultural Library King County Library System Lorcan Dempsey Seattle, WA Vice President, Programs and Research, Robert Wolven and Chief Strategist Associate University Librarian for OCLC, Inc. Bibliographic Services and Jay Girotto Collection Development Windows Live Search Columbia University Group Program Manager Microsoft Corporation Project Consultants José-Marie Griffiths (Co-Chair) Karen Coyle Dean and Professor Library Consultant School of Information and Library -

International Literacy Year 1990: Building the Momentum. Report Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 301 690 CE 051 454 AUTHOR Marshall, Judith TITLE International Literacy Year 1990: Building the Momentum. Report of the Meeting of the International Task Force on Literacy (2nd, West Berlin, Federal Republic of Germany, June 5-10, 1988). INSTITUTION International Council for Adult Education, Toronto (Ontario). PUB DATE 88 NOTE 33p. AVAILABLE FROM International Task Force on Literacy Coordinating Office, 720 Bathurst Street, Suite 500, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2R4 ($5.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021) -- Reports Descriptive (141) EARS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; Developed Nations; Developing Nations; Foreign Countries; *Illiteracy; International Cooperation; *International Programs; Literacy; *Literacy Education; *Publicity; Public Support IDENTIFIERS International Literacy Year 1990 ABSTRACT This report prov-des materials from the second meeting of the International Task Force on Literacy (ITFL), which focused on specific goals and targets for nongovernmental organization (NGO) mobilization for 1990, International Literacy Year (ILY). Section 2 discusses issues that emerged as central to workin literacy, including literacy, democracy, and empowerment; images of literacy and the illiterate; technical/pedagogical goals versus political/ideological goals; role of teachers in literacy, illiteracy in industrialized countries; women's experiences of literacy; Unesco's vital role in literacy; how high a priority literacy really is; literacy actions by NG0s; and a research agenda for literacy. Section 3 summarizes these reports to the Task Force: International Council for Adult Education Needs Assessment Survey of Member Associations, a project proposal for a video-based resource package linking the theme of peace to literacy; a proposal to create a special book for ILY written by literacy learner and proposals to educate and mobilize world public opinion about -.Lteracy through the arts. -

National Report from Sweden in the Third Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review

National report from Sweden in the third cycle of the Universal Periodic Review Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................... 3 1.1 Method and consultation process ................................................................... 4 2. Protecting human rights .................................................................. 4 2.1 National human rights strategy ....................................................................... 4 2.2 International human rights conventions ........................................................ 5 2.2.1 Incorporation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child into Swedish law ................................................................................................. 5 2.2.2 Ratification of the Third Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on a communications procedure ............................. 5 2.2.3 Ratification of ILO Convention No. 169 on indigenous and tribal peoples ................................................................................................................. 6 2.2.4 Ratification of ILO Convention No. 189 on decent work for domestic workers ................................................................................................ 6 2.2.5 Ratification of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families .......... 6 2.3 Establishment of an independent national human rights institution and human rights in -

Prostitution Policy in Sweden – Targeting Demand Contents

THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE PROSTITUTION POLICY IN SWEDEN – TARGETING DEMAND CONTENTS The Swedish Institute (SI) is a public agency PAGES 4–15 PROSTITUTION POLICY IN SWEDEN that promotes interest and confidence – TARGETING DEMAND in Sweden around the world. SI seeks to establish co-operation and lasting relations 5 – Other countries’ policy models with other countries through strategic 6 – The inherent power imbalance of sex trade communication and exchange in the fields – Effects of the law – current situation of culture, education, science and business. 6 9 – Findings from 2014 COPYRIGHT 9 – Why Sweden? Anthony Jay and the Swedish Institute 11 – A nation dedicated to gender equality AUTHOR 13 – Children’s rights Anthony Jay Olsson 14 – The issue of consent and agency EDITOR 15 – The link between prostitution and trafficking Rikard Lagerberg, Lagerberg Media FACT-CHECKING PAGES 16–21 TIMELINE Per-Anders Sunesson Ambassador at Large for Combating Trafficking in Persons, PAGES 22–25 INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS Ministry for Foreign Affairs 23 – The United Nations Thomas Ahlstrand 23 – The Council of Europe Senior prosecutor, Swedish Prosecution Authority 24 – The European Union Petra Tammert Seidefors Senior officer | THB team, PAGES 26–34 STATISTICS Swedish Gender Equality Agency Endrit Mujaj 27 – Europe, Victims of trafficking Adviser, Council of the Baltic Sea 28 – Europe, Number of victims States – Task Force against Trafficking 30 – Sweden, Crime statistics in Human Beings Olga Persson 32 – Sweden, Human trafficking Secretary General, Unizon 34 – Sweden, Crime statistics 1999–2017 GRAPHIC DESIGN BankerWessel PAGE 35 LINKS, #, CAMPAIGNS AND FURTHER RESOURCE MATERIALS ISBN Prostitution policy in Sweden – targeting demand: 978-91-86995-88-1 2019 Front cover photo by Mitchell Griest 4 PROSTITUTION POLICY IN SWEDEN TARGETING DEMAND 5 THIS NEW LAW clearly changed the perception and focus away from the person involved in prostitution and towards the buyer PROSTITUTION of sexual services and hence the person responsible for prosti- tution. -

National Referral Mechanism

National Referral Mechanism Protecting and supporting victims of Trafficking in Human Beings in Sweden Report 2016:29 NMT consists of governmental authorities working against prostitution and human trafficking and functions as a strategic resource for developing and increasing the efficiency of cooperation in the work against human trafficking. The cooperation focuses particularly on supporting municipalities and regions which have limited experience with the work against prostitution and human trafficking. NMT offers operational method support to municipalities, governmental authorities and NGOs in human trafficking cases through its Helpline: 020-390 000 and through their website www.nmtsverige.se. Project leader: Endrit Mujaj Year of publication: 2016 Report: 2016:29 ISBN: 978-91-7281-711-1 For further information contact Social Development unit. County Administrative Board of Stockholm Phone: 010-223 10 00 You can find all our reports here: www.lansstyrelsen.se/stockholm/publikationer Foreword Trafficking in Human Beings, regardless of the form of the exploitation, is a great challenge for the society and can only be countered through multidisciplinary and international cooperation. A long-term effort against human trafficking requires that victims are offered support, protection, reflection period and are given opportunities and alternatives in order to rebuild their lives. Therefore, it is highly important that professionals who identify presumed victims act. A single suspicion can be enough. Since the Spring of 2014, the County Administrative Board in Stockholm, in its function as the National Coordinator against prostitution and human trafficking, has worked to develop a National Referral Mechanism-manual (NRM). The manual is based on existing legislation and operative experiences. -

Symptoms of a Broken System: the Gender Gaps in COVID-19 Decision- Making

Commentary BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003549 on 1 October 2020. Downloaded from Symptoms of a broken system: the gender gaps in COVID-19 decision- making 1,2 3 2 Kim Robin van Daalen , Csongor Bajnoczki, Maisoon Chowdhury, Sara Dada,2,4 Parnian Khorsand,2 Anna Socha,3 Arush Lal,2 Laura Jung,2,5 6 7 8,9 Lujain Alqodmani, Irene Torres , Samiratou Ouedraogo, 10,11 2 12 3 Amina Jama Mahmud, Roopa Dhatt, Alexandra Phelan, Dheepa Rajan To cite: van Daalen KR, A growing chorus of voices are questioning Summary box Bajnoczki C, Chowdhury M, the glaring lack of women in COVID-19 et al. Symptoms of a broken system: the gender gaps decision- making bodies. Men dominating ► Despite numerous global and national commit- in COVID-19 decision- leadership positions in global health has long ments to gender- inclusive global health governance, making. BMJ Global Health been the default mode of governing. This is COVID-19 followed the usual modus operandi –ex- 2020;5:e003549. doi:10.1136/ a symptom of a broken system where gover- cluding women’s voices. A mere 3.5% of 115 iden- bmjgh-2020-003549 nance is not inclusive of any type of diversity, tified COVID-19 decision- making and expert task be it gender, geography, sexual orientation, forces have gender parity in their membership while Handling editor Seye Abimbola race, socio-economic status or disciplines 85.2% are majority men. within and beyond health – excluding those ► With 87 countries included in this analysis, informa- Received 27 July 2020 tion regarding task force composition and member- Revised 22 August 2020 who offer unique perspectives, expertise and ship criteria was not easily publicly accessible for Accepted 24 August 2020 lived realities. -

No Time for Losers

Dietrich Helms, Thomas Phleps (Hg.) No Time for Losers 2008-08-05 10-26-05 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0291185826883360|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 983.p 185826883368 Beiträge zur Popularmusikforschung 36 Herausgegeben von Dietrich Helms und Thomas Phleps Editorial Board: Dr. Martin Cloonan (Glasgow) | Prof. Dr. Ekkehard Jost (Gießen) Prof. Dr. Rajko Mursˇicˇ (Ljubljana) | Prof. Dr. Winfried Pape (Gießen) Prof. Dr. Helmut Rösing (Hamburg) | Prof. Dr. Mechthild von Schoenebeck (Dortmund) | Prof. Dr. Alfred Smudits (Wien) 2008-08-05 10-26-05 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0291185826883360|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 983.p 185826883376 Dietrich Helms, Thomas Phleps (Hg.) No Time for Losers. Charts, Listen und andere Kanonisierungen in der populären Musik 2008-08-05 10-26-05 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0291185826883360|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 983.p 185826883392 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Umschlaggestaltung: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Umschlagabbildung: Sandra Wendeborn: »GlamGLowGLitter«, © Photocase 2008 Lektorat: Ralf von Appen und André Doehring Satz: Ralf von Appen Druck: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-983-1 Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier mit chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff. Besuchen Sie uns im Internet: http://www.transcript-verlag.de Bitte fordern Sie unser Gesamtverzeichnis und andere Broschüren an unter: [email protected] 2008-08-05 10-26-06 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0291185826883360|(S. -

2012 CTTSO Review Book (Pdf)

Preface New ways to wage war – and to wage terror – promise both small and large changes in established Therefore, just as water assumptions. But “ whether that technique is a new explosive retains no constant shape, mixture, a computer virus, or a disinformation so in warfare, there are campaign, it always goes back to the same no constant conditions. assumptions. The ” attacker is always trying Sun Tzu, to get by the defender, The Art of War and the defender is trying to deploy the right countermove. New threats require new strategies. Innovation enables the United States to increase our own defenses, identify weaknesses in those who attack us and our allies, and change the rules in our favor. Innovation has many forms. It ranges from basic research – technology that will not be available for decades but that promises to truly alter how we understand and interact with the world – to small, but key, innovations, to current equipment with delivery schedules measured in days, weeks, or months. All are essential, and all must work in concert. In a time when innovation often comes from new and emerging companies, it is interesting to look at an organization that has been involved with innovation for more than 25 years. The Combating Terrorism Technical Support Office (CTTSO) doesn’t just pursue innovation for the sake of innovation – it pursues innovation to meet the needs of its diverse user base. A new way to build blast- resistant buildings is one thing, but it only becomes powerful when directly meeting the needs of the people who live and work in those buildings.