Native Amphibian Restoration and Monitoring in Bucks Lake Wilderness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

Public Law 98-425 An

PUBLIC LAW 98-425-SEPT. 28, 1984 98 STAT. 1619 Public Law 98-425 98th Congress An Act Sept. 28, 1984 Entitled the "California Wilderness Act of 1984". [H.R. 1437] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That this title may California Wilderness Act be cited as the "California Wilderness Act of 1984". of 1984. National TITLE I Wilderness Preservation System. DESIGNATION OF WILDERNESS National Forest System. SEC. 101. (a) In furtherance of the purposes of the Wilderness Act, National parks, the following lands, as generally depicted on maps, appropriately monuments, etc. referenced, dated July 1980 (except as otherwise dated) are hereby 16 USC 1131 designated as wilderness, and therefore, as components of the Na note. tional Wilderness Preservation System- (1)scertain lands in the Lassen National Forest, California,s which comprise approximately one thousand eight hundred acres, as generally depicted on a map entitled "Caribou Wilder ness Additions-Proposed", and which are hereby incorporated in, and which shall be deemed to be a part of the Caribou Wilderness as designated by Public Law 88-577; 16 USC 1131 (2)s certain lands in the Stanislaus and Toiyabe Nationals note. 16 USC 1132 Forests, California, which comprise approximately one hundred note. sixty thousand acres, as generally depicted on a map entitled "Carson-Iceberg Wilderness-Proposed", dated July 1984, and which shall be known as the Carson-Iceberg Wilderness: Pro vided, however, That the designation of the Carson-Iceberg Wil derness shall not preclude continued motorized access to those previously existing facilities which are directly related to per mitted livestock grazing activities in the Wolf Creek Drainage on the Toiyabe National Forest in the same manner and degree in which such access was occurring as of the date of enactment of this title; (3)scertain lands in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Cali 16 USC 1132 fornia, which comprise approximately seven thousand three note. -

Fen Restoration in the Bucks Lake Wilderness

SIERRA CASCADE PROVINCE ECOLOGY PROGRAM | USDA FOREST SERVICE REGION 5 Fen Restoration in the Bucks Lake Wilderness Fens are Restoring wetlands is never easy, but restoration in a remote wilderness area with- unique out the use of mechanized equipment is even more challenging! With the help of wetland numerous partners and volunteers, the Plumas National Forest restored several ecosystems fen wetlands in the Bucks Lake Wilderness during the summer of 2017. that support rare plants and animals, Key Findings sequester The Bucks Lake Wilderness on the Plumas National Forest supports numerous carbon, and fen wetlands, but some of them have been degraded as a result of cattle grazing, provide altered hydrology, and drought. insight into Restoration of these fen wetlands required planting thousands of sedges, filling past climates erosion gullies and channels, and installing fences to exclude livestock. and vegetation. Seeds were collected by Colorado State University students from fens in the Bucks Lake Wilder- ness and grown in a nursery. Many fen wetlands show signs of degradation, including exposed peat and altered hydrology. Temporary fencing was installed with assistance from the The Bucks Lake Wilderness supports a number of rare fen Feather River Land Trust to exclude livestock until fen vegeta- wetlands. tion can re-establish FOREST SERVICE CONTACT: KYLE MERRIAM, (530) 283-7777; [email protected] AUGUST 2017 USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender. SIERRA CASCADE PROVINCE ECOLOGY PROGRAM | USDA FOREST SERVICE REGION 5 Project Overview In order to comply with wilderness regulations, restoring fens in the Bucks Lake Wilderness had to be accomplished without vehicles or machinery of any kind. -

Bucks Lake Wilderness Plumas National Forest ,\N Mt

Bucks Lake Wilderness Plumas National Forest ,\N Mt. Hough Ranger District California Wilderness Act of 1984 The Bucks Lake Wilderness came into being with ,.n the passage of the California Wilderness Act in ' 1984. The Act allowed 23,578 acres of the Plumas ,,. National Forest to be set aside and protected as part of the National Forest Wilderness System. ,��f;ii, ! ;;..�·--� ; . ,c.-::- �_:._ / :{ Wilderness areas in the National Forest system are to be managed to preserve the natural Permits are not required to enter the Wilderness, processes, native vegetation and wildlife. but we do ask you to sign in at each trailhead you Wilderness is a place where people can visit, but are hiking. not remain. In the wilderness, preservation of the Wilderness trails are popular with equestrian riders land is the first priority, while human use is and provide miles of horse-friendly trails along with secondary. many opportunities for overnight camping. Please As part of the Wilderness Act, no motorized make sure to note which trails have been vehicles are allowed inside the wilderness area. recommended for horses. Mechanized equipment and wheeled vehicles are For more detailed information, a Bucks Lake NOT allowed either. Therefore, no jeeps, 4 Wilderness map can be purchased at any Forest wheelers, Razors, bicycles, wheelbarrows, carts or Service office on the Plumas National Forest, hang gliders are allowed to be used here. Hikers or contact the Mt. Hough Ranger District at are welcome as well as saddle and pack stock. (530) 283-0555 You may see cattle in the wilderness area from August 1 through September 30. -

Guidelines for Evaluating Air Pollution Impacts on Class I Wilderness Areas in California

United States Department of Agriculture Guidelines for Evaluating Air Forest Service Pollution Impacts on Class I Pacific Southwest Research Station General Technical Wilderness Areas in California Report PSW-GTR-136 David L. Peterson Daniel L. Schmoldt Joseph M. Eilers Richard W. Fisher Robert D. Doty Peterson, David L.; Schmoldt, Daniel L.; Eilers, Joseph M.: Fisher, Richard W.; Doty, Robert D. 1992. Guidelines for evaluating air pollution impacts on class I wilderness areas in California. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR- 136. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, US. Department of Agriculture; 34 p. The 1977 Clean Air Act legally mandated the prevention of significant deterioration (PSD) of air quality related values (AQRVs) on wilderness lands. Federal land managers are assigned the task of protecting these wilderness values. This report contains guidelines for determining the potential effects of incremental increases in air pollutants on natural resources in wilderness areas of the National Forests of California. These guidelines are based on current information about the effects of ozone, sulfur, and nitrogen on AQRVs. Knowledge-based methods were used to elicit these guidelines from scientists and resource managers in a workshop setting. Linkages were made between air pollutant deposition and level of deterioration of specific features (sensitive receptors) of AQRVs known to be sensitive to pollutants. Terrestrial AQRVs include a wide number of ecosystem types as well as geological and cultural values. Ozone is already high enough to injure conifers in large areas of California and is a major threat to terrestrial AQRVs. Aquatic AQRVs include lakes and streams, mostly in high elevation locations. -

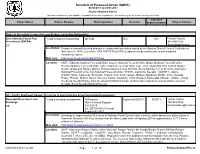

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2017 to 03/31/2017 Plumas National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2017 to 03/31/2017 Plumas National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) Sierra Nevada Forest Plan - Land management planning On Hold N/A N/A Donald Yasuda Amendment (SNFPA) 916-640-1168 EIS [email protected] Description: Prepare a narrowly focused analysis to comply with two orders issued by the Eastern District Court of California on November 4, 2009. Correct the 2004 SNFPA Final SEIS to address range of alternatives and analytical consistency issues. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/r5/snfpa/2010seis Location: UNIT - Eldorado National Forest All Units, Lassen National Forest All Units, Modoc National Forest All Units, Sequoia National Forest All Units, Tahoe National Forest All Units, Lake Tahoe Basin Mgt Unit, Carson Ranger District, Bridgeport Ranger District, Plumas National Forest All Units, Sierra National Forest All Units, Stanislaus National Forest All Units, Inyo National Forest All Units. STATE - California, Nevada. COUNTY - Alpine, Amador, Butte, Calaveras, El Dorado, Fresno, Inyo, Kern, Lassen, Madera, Mariposa, Modoc, Mono, Nevada, Placer, Plumas, Shasta, Sierra, Siskiyou, Tulare, Tuolumne, Yuba, Douglas, Esmeralda, Mineral. LEGAL - Along the Sierra Nevada Range, from the Oregon/California border south to Lake Isabella as well as lands in western Nevada. Sierra Nevada National Forests. R5 - Pacific Southwest Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Mammoth Base Area Land - Land ownership management In Progress: Expected:09/2018 09/2018 Janelle Walker Exchange NOI in Federal Register 760-924-5523 EIS 08/23/2016 [email protected] Est. -

Dixie Fire Incident Update

DIXIE FIRE INCIDENT UPDATE Date: 7/30/2021 Time: 7:00 p.m. @CALFIRE_ButteCo @CALFIREButteCo Information Line: (530) 538-7826 @USFSPlumas @USFSPlumas Media Line: (530) 588-0845 @LassenNF @LassenNF Incident Website: www.fire.ca.gov INCIDENT FACTS Incident Start Date: 7/13/2021 Incident Start Time: 5:15 p.m. Incident Type: Vegetation Cause: Under Investigation Incident Location: Feather River Canyon near Cresta Powerhouse CAL FIRE Unit: Butte Unified Command Agencies: CAL FIRE, United States Forest Service Size: 240,795 acres Containment: 24% Expected Full Containment: Unknown Civilian Injuries/Fatalities: 0 Firefighter Injuries/Fatalities: 0 Structures Destroyed: 43 Structures Damaged: 5 Structures Threatened: 10,657 Other Minor Structures: 22 Other Minor Structures: 4 CURRENT SITUATION Incident Update Dixie Fire West Zone - Dixie Fire West Zone – Potential exist for increased fire activity tonight. The fire continues to move inside control lines towards unburned interior islands as planned. Due to this interior fire production, pyrocumulus clouds have developed which can be visible from miles away. Firefighters will use optimal conditions at night to improve fire line, increase containment, assess, and protect structures and infrastructure. To date, 200,030 gallons of retardant have been applied to protect valuable structures and timber. Fire activity along Hwy 70 has diminished and transitioned to patrol status, felling for hazardous trees that threaten control lines, and extinguishing hot spots. Dixie Fire East Zone - On the East Zone, crews made good progress Friday, as thunderstorms did not develop until late afternoon. In the northwest section, crews were able to protect homes and structures along the Rush Creek Road, as the fire burned towards the former Chips Fire burn scar in the Red Hill area between State Route 70 and Muggins Creek. -

Wilderness Areas Along the Pacific Crest Trail

Vancouver C A N A B D R I T I A S H C O Wilderness Areas L U M B MT BAKER- 1 I A OKANO G SNOQ 2 AN- UALMIE along the WE N ATCHEE NATIONAL 3 LO YMPIC NATIONAL NATIONAL FOREST Pacific Crest Trail FOREST Seattle 4 FOREST 5 50 years of Wilderness on the PCT W A S H I N On Sept. 3, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law, recognizing 7 6 G T O placesN “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself 8 GIFFORD PINCH is a visitor who does not remain.” O NATIONALT 9 FOREST Countless people have passed and will continue to pass through America’s most treasured land- 10 scapes, including the 48 wilderness areas that include the Pacific Crest Trail. 11 Portland The Wilderness Act established the National Wilderness Preservation System and set aside an 12 initial 9.1 million acres of wild lands for the use and benefit of the American people. Over the past MT HOOD 13 50 years, Congress has added more than 100 million acres to this unique land preservation system. NATIONAL FOREST To learn more about the country’s wilderness areas, visit www.wilderness.net. SIUSL A W NATIONAL FOREST O 1 Pasayten Wilderness – Oct. 2, 1968 R 14 E G 15 O N 2 Stephen Mather Wilderness – Nov. 16, 1988 (Wash. Park Wilderness Act of 1988) WILLAMETTE 16 NATIONAL DESCHUTES 3 Glacier Peak Wilderness – Sept. 3, 1964 (Wilderness Act) FOREST NATIONAL 4 Henry M. -

Butte County Forest Advisory Committee

BUTTE COUNTY FOREST ADVISORY COMMITTEE January 23, 2017 - 5:00 P.M. Meeting ITEM NO. 1.00 Call to order – Butte County Public Works Facility, 44 Bellarmine Ct., Chico, CA 2.00 Pledge of allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America (if American flag is present) 2.01 Roll Call - Invited Guests: Cindi Dunsmoor (Butte County OEM), Randall Gould (Feather River District Ranger, Plumas NF), Kathleen Nelson (Almanor District Ranger, Lassen NF), Stacy Kroner (Lassen NF); Laura Page (Congressman La Malfa), Dave Derby (Cal Fire), Sarah Reynolds (BCRCD); Dennis Schmidt (Coordinating Committee), Tim Snellings (Coordinating Committee), Glenn Lunak (Forester) _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 3.00 Consent Agenda 3.01 Review and approve minutes of 12-19-16 4.00 Agenda 4.01 Self-Introduction of Forest Advisory Committee Members, Alternates, Guests and Public – 5 Min. 4.02 Confirmation of Board Appointments: Recreation-Motorized: Repanich as Member, Severin as Alternate Economic Tourism: Walker as Member, Shary as Alternate 4.03 Election of Officers: Chair and Vice-Chair 4.04 OHV Grant Meetings with Plumas NF Debrief – Severin/Repanich 4.05 BLM Letter (due 2-03-17) to be considered by Board at meeting of 1-24-17, derived from January 2 FAC Workshop. Debrief of BLM Public Outreach meeting of January 9 and 18 from FAC attendees. 15 Min. 4.06 General Plan (GP2030) amendments – develop ideas for incorporation in to the GP2030 (l hour) 4.07 SOPA Review – Current Quarter: Discussion & required FAC action for projects affecting Butte County listed in 2017 SOPA Reports for Lassen and Plumas NF’s. -

Gold Lake (Bucks Lake Wilderness)

State of California Memorandum Date: 4/18/2018 To: Sarah Mussulman From: Isaac Chellman Senior Environmental Scientist Environmental Scientist Sierra District Supervisor High Mountain Lakes North Central Region Fisheries North Central Region Fisheries Ec: CDFW Document Library Cc: Region 2 Fish Files Subject: Native amphibian restoration and monitoring in Bucks Lake Wilderness. GOLD LAKE FISH REMOVAL AND ROCK LAKE RANA SIERRAE MONITORING. Brook trout removal activities are complete in the Gold Lake drainage (Figure 1); California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) staff removed 254 brook trout to benefit Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs (Rana sierrae, SNYLF). Amphibian monitoring data from 2012 through 2017 suggest a very small but stable SNYLF population; because of its size, this population remains extremely vulnerable to extirpation. CDFW will continue amphibian monitoring the in area to document SNYLF response to fish removal. Figure 1: Bucks Lake Wilderness, Plumas County, CA. Green dots showing Rana sierrae (SNYLF) sites include positive detections by CDFW staff during visual encounter surveys (VES) between 2004 and 2017. ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING Bucks Lake Wilderness is located in western Plumas County, south of Interstate 70 and north of Bucks Lake Reservoir, and consists of 9,695 hectares. The Pacific Crest Trail bisects the wilderness from north to south, and local elevations range from around 2,400 feet (730 meters [m]) above mean sea level near the northern border along the Feather River, to 7,067 feet (2,154 m) at the summit of Mount Pleasant. CDFW crews observed two SNYLF populations in Bucks Lake Wilderness while conducting baseline surveys in 2003 and 2004. -

Northwest California Wilderness, Recreation, and Working Forests Act

116TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 116–389 NORTHWEST CALIFORNIA WILDERNESS, RECREATION, AND WORKING FORESTS ACT FEBRUARY 4, 2020.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. GRIJALVA, from the Committee on Natural Resources, submitted the following R E P O R T together with DISSENTING VIEWS [To accompany H.R. 2250] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Natural Resources, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. 2250) to provide for restoration, economic development, recreation, and conservation on Federal lands in Northern Cali- fornia, and for other purposes, having considered the same, report favorably thereon with an amendment and recommend that the bill as amended do pass. The amendment is as follows: Strike all after the enacting clause and insert the following: SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Northwest California Wilderness, Recreation, and Working Forests Act’’. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. Definitions. TITLE I—RESTORATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Sec. 101. South Fork Trinity-Mad River Restoration Area. Sec. 102. Redwood National and State Parks restoration. Sec. 103. California Public Lands Remediation Partnership. Sec. 104. Trinity Lake visitor center. Sec. 105. Del Norte County visitor center. Sec. 106. Management plans. Sec. 107. Study; partnerships related to overnight accommodations. TITLE II—RECREATION Sec. 201. Horse Mountain Special Management Area. 99–006 VerDate Sep 11 2014 08:14 Feb 07, 2020 Jkt 099006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6659 Sfmt 6631 E:\HR\OC\HR389.XXX HR389 2 Sec. -

The Wilderness Act of 1964

The Wilderness Act of 1964 Source: US House of Representatives Office of the Law This is the 1964 act that started it all Revision Counsel website at and created the first designated http://uscode.house.gov/download/ascii.shtml wilderness in the US and Nevada. This version, updated January 2, 2006, includes a list of all wilderness designated before that date. The list does not mention designations made by the December 2006 White Pine County bill. -CITE- 16 USC CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM 01/02/2006 -EXPCITE- TITLE 16 - CONSERVATION CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -HEAD- CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -MISC1- Sec. 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of policy; wilderness areas; administration for public use and enjoyment, protection, preservation, and gathering and dissemination of information; provisions for designation as wilderness areas. (b) Management of area included in System; appropriations. (c) "Wilderness" defined. 1132. Extent of System. (a) Designation of wilderness areas; filing of maps and descriptions with Congressional committees; correction of errors; public records; availability of records in regional offices. (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classifications as primitive areas; Presidential recommendations to Congress; approval of Congress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Eagles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado. (c) Review by Secretary of the Interior of roadless areas of national park system and national wildlife refuges and game ranges and suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; authority of Secretary of the Interior to maintain roadless areas in national park system unaffected. (d) Conditions precedent to administrative recommendations of suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; publication in Federal Register; public hearings; views of State, county, and Federal officials; submission of views to Congress.