An Auteur Analysis of Films Directed by Adrian Lyne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Suggested Texts for Teaching Film to A-Level Language Students

School of Languages, Cultures and Societies (2015) Suggested texts for teaching film to A-Level language students Each of the academics representing an area of language/culture study in the videos has also offered some general notes and advice surrounding texts which could help support the teaching of each relevant area. French (Diana Holmes) Films Truffaut Les 400 Coups (1959) – iconic New Wave film, interesting formally, but also about childhood, schooldays, relations with adults. Intensely moving as well as wonderful cinema – and introduces an important director. Louis Malle’s Au Revoir les enfants (1987). Relevant for any study of Occupation years, but also a good film and important director. Malle’s Lacombe Lucien (1974) is possibly even better. (Fairly) recent commercial successes such as Jeunet’s Amélie (2001) or Les Intouchables (Toledano and Nakache, 2011) – or Tout ce qui brille by Géraldine Nakache (2010) would be interesting to do, looking in part at the reasons for their popularity. This year’s Bande de filles (Céline Sciamma – a very interesting director). There is the unavoidable La Haine – very predictable choice, but it always goes down well and it is brilliant. Books For film ‘language’ see: Warren Buckland: (Teach yourself) Film Studies (Hodder & Stoughton, 1998) H-Paul Chevrier: Le Langage du cinéma narratif (Les 400 coups, 2005) School of Languages, Cultures and Societies (2015) For history/analysis of French cinema see: Guy Austin: Contemporary French Cinema (Manchester University Press, 1996; Second edition – updated -

Locations of Motherhood in Shakespeare on Film

Volume 2 (2), 2009 ISSN 1756-8226 Locations of Motherhood in Shakespeare on Film LAURA GALLAGHER Queens University Belfast Adelman’s Suffocating Mothers (1992) appropriates feminist psychoanalysis to illustrate how the suppression of the female is represented in selected Shakespearean play-texts (chronologically from Hamlet to The Tempest ) in the attempted expulsion of the mother in order to recover the masculine sense of identity. She argues that Hamlet operates as a watershed in Shakespeare’s canon, marking the prominent return of the problematic maternal presence: “selfhood grounded in paternal absence and in the fantasy of overwhelming contamination at the site of origin – becomes the tragic burden of Hamlet and the men who come after him” (1992, p.10). The maternal body is thus constructed as the site of contamination, of simultaneous attraction and disgust, of fantasies that she cannot hold: she is the slippage between boundaries – the abject. Julia Kristeva’s theory of the abject (1982) ostensibly provides a hypothesis for analysis of women in the horror film, yet the theory also provides a critical means of situating the maternal figure, the “monstrous- feminine” in film versions of Shakespeare (Creed, 1993, 1996). Therefore the choice to focus on the selected Hamlet , Macbeth , Titus Andronicus and Richard III film versions reflects the centrality of the mother figure in these play-texts, and the chosen adaptations most powerfully illuminate this article’s thesis. Crucially, in contrast to Adelman’s identification of the attempted suppression of the “suffocating mother” figures 1, in adapting the text to film the absent maternal figure is forced into (an extended) presence on screen. -

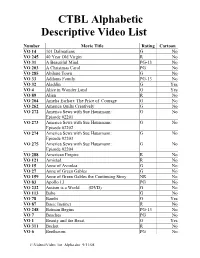

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List Number Movie Title Rating Cartoon VO 14 101 Dalmatians G No VO 245 40 Year Old Virgin R No VO 31 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 No VO 203 A Christmas Carol PG No VO 285 Abilene Town G No VO 33 Addams Family PG-13 No VO 32 Aladdin G Yes VO 4 Alice in Wonder Land G Yes VO 89 Alien R No VO 204 Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage G No VO 262 America Quilts Creatively G No VO 272 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2201 VO 273 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2202 VO 274 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2203 VO 275 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2204 VO 288 American Empire R No VO 121 Amistad R No VO 15 Anne of Avonlea G No VO 27 Anne of Green Gables G No VO 159 Anne of Green Gables the Continuing Story NR No VO 83 Apollo 13 PG No VO 232 Autism is a World (DVD) G No VO 113 Babe G No VO 78 Bambi G Yes VO 87 Basic Instinct R No VO 248 Batman Begins PG-13 No VO 7 Beaches PG No VO 1 Beauty and the Beast G Yes VO 311 Becket R No VO 6 Beethoven PG No J:\Videos\Video_list_Alpha.doc 9/11/08 VO 160 Bells of St. Mary’s NR No VO 20 Beverly Hills Cop R No VO 79 Big PG No VO 163 Big Bear NR No VO 289 Blackbeard, The Pirate R No VO 118 Blue Hawaii NR No VO 290 Border Cop R No VO 63 Breakfast at Tiffany's NR No VO 180 Bridget Jones’ Diary R No VO 183 Broadcast News R No VO 254 Brokeback Mountain R No VO 199 Bruce Almighty Pg-13 No VO 77 Butch Cassidy and the Sun Dance Kid PG No VO 158 Bye Bye Blues PG No VO 164 Call of the Wild PG No VO 291 Captain Kidd R No VO 94 Casablanca -

Jodie Foster Une Certaine Idée De La Femme Sylvie Gendron

Document generated on 09/30/2021 10:09 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Jodie Foster Une certaine idée de la femme Sylvie Gendron L’ONF : U.$. qu’on s’en va? Number 176, January–February 1995 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/49736ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Gendron, S. (1995). Jodie Foster : une certaine idée de la femme. Séquences, (176), 30–33. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 1994 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Gros plan Jodie Une certaine idée Dire de Jodie Foster qu'elle est une actrice remarquable à tous points de vue est à la fois une réalité et une observation d'une banalité sans nom. Il n'y a qu'à voir ses films pour constater son talent. Ne retenons que ceux qui sont dignes d'intérêt et ils sont assez nombreux. The Silence of the Lambs 1 serait bien vain et surtout redondant de chercher fance; ce pouvait aussi être un rêve de pédophile. Je — dans le vrai sens du terme — prétendant être des à chanter sur tous les tons les louanges de la belle reste convaincue que les publicitaires de l'époque adultes. -

Abel Ferrara

A FILM BY Abel Ferrara Ray Ruby's Paradise, a classy go go cabaret in downtown Manhattan, is a dream palace run by charismatic impresario Ray Ruby, with expert assistance from a bunch of long-time cronies, sidekicks and colourful hangers on, and featuring the most beautiful and talented girls imaginable. But all is not well in Paradise. Ray's facing imminent foreclosure. His dancers are threatening a strip-strike. Even his brother and financier wants to pull the plug. But the dreamer in Ray will never give in. He's bought a foolproof system to win the Lottery. One magic night he hits the jackpot. And loses the ticket... A classic screwball comedy in the madcap tradition of Frank Capra, Billy Wilder and Preston Sturges, from maverick auteur Ferrara. DIRECTOR’S NOTE “A long time ago, when 9 and 11 were just 2 odd numbers, I lived above a fire house on 18th and Broadway. Between the yin and yang of the great Barnes and Noble book store and the ultimate sports emporium, Paragon, around the corner from Warhol’s last studio, 3 floors above, overlooking Union Square. Our local bar was a gothic church made over into a rock and roll nightmare called The Limelite. The club was run by a gang of modern day pirates with Nicky D its patron saint. For whatever reason, the neighborhood became a haven for topless clubs. The names changed with the seasons but the core crews didn't. Decked out in tuxes and razor haircuts, they manned the velvet ropes that separated the outside from the in, 100%. -

INTRODUCTION Fatal Attraction and Scarface

1 introduction Fatal Attraction and Scarface How We Think about Movies People respond to movies in different ways, and there are many reasons for this. We have all stood in the lobby of a theater and heard conflicting opin- ions from people who have just seen the same film. Some loved it, some were annoyed by it, some found it just OK. Perhaps we’ve thought, “Well, what do they know? Maybe they just didn’t get it.” So we go to the reviewers whose business it is to “get it.” But often they do not agree. One reviewer will love it, the next will tell us to save our money. What thrills one person may bore or even offend another. Disagreements and controversies, however, can reveal a great deal about the assumptions underlying these varying responses. If we explore these assumptions, we can ask questions about how sound they are. Questioning our assumptions and those of others is a good way to start think- ing about movies. We will soon see that there are many productive ways of thinking about movies and many approaches that we can use to analyze them. In Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1992), the actor playing Bruce Lee sits in an American movie theater (figure 1.1) and watches a scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) in which Audrey Hepburn’s glamorous character awakens her upstairs neighbor, Mr Yunioshi. Half awake, he jumps up, bangs his head on a low-hanging, “Oriental”-style lamp, and stumbles around his apart- ment crashing into things. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries. -

Female Authorship in the Slumber Party Massacre Trilogy

FEMALE AUTHORSHIP IN THE SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE TRILOGY By LYNDSEY BROYLES Bachelor of Arts in English University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 2016 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2019 FEMALE AUTHORSHIP IN THE SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE TRILOGY Thesis Approved: Jeff Menne Thesis Adviser Graig Uhlin Lynn Lewis ii Name: LYNDSEY BROYLES Date of Degree: MAY, 2019 Title of Study: FEMALE AUTHORSHIP IN THE SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE TRILOGY Major Field: ENGLISH Abstract: The Slumber Party Massacre series is the only horror franchise exclusively written and directed by women. In a genre so closely associated with gender representation, especially misogynistic sexual violence against women, this franchise serves as a case study in an alternative female gaze applied to a notoriously problematic form of media. The series arose as a satire of the genre from an explicitly feminist lesbian source only to be mediated through the exploitation horror production model, which emphasized female nudity and violence. The resulting films both implicitly and explicitly address feminist themes such as lesbianism, trauma, sexuality, and abuse while adhering to misogynistic genre requirements. Each film offers a unique perspective on horror from a distinctly female viewpoint, alternately upholding and subverting the complex gender politics of women in horror films. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................1