Towards a Scientific Conception of Free Will

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philosophy of A.J. Ayer, with Replies 55 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS FRONTISPIECE iv INTRODUCTION vii FOUNDER'S GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE LIBRARY OF LIVING PHILOSOPHERS ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xii PREFACE XVll PART ONE: INTELLECTUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A.J. AYER 1 Facsimile of Ayer's Handwriting 2 A.J. Ayer: My Mental Development 3 Still More of My Life 41 PART TWO: DESCRIPTIVE AND CRITICAL ESSAYS ON THE PHILOSOPHY OF A.J. AYER, WITH REPLIES 55 1. Evandro Agazzi: Varieties of Meaning and Truth 57 2. James Campbell: Ayer and Pragmatism 83 REPLY TO JAMES CAMPBELL 105 3. David S. Clarke, Jr.: On Judging Sufficiency of Evidence 109 REPLY TO DAVID S. CLARKE, JR. 125 4. Michael Dummett: The Metaphysics of Verificationism 128 REPLY TO MICHAEL DUMMETT 149 5. Elizabeth R. Eames: A.J. Ayer's Philosophical Method 157 REPLY TO ELIZABETH R. EAMES 175 6. John Foster: The Construction of the Physical World 179 REPLY TO JOHN FOSTER 198 xiv TABLE OF CONTENTS 7. Paul Gochet: On Sir Alfred Ayer's Theory of Truth 201 REPLY TO PAUL GOCHET 220 8. Martin Hollis: Man as a Subject for Social Science 225 REPLY TO MARTIN HOLLIS 237 9. Ted Honderich: Causation: One Thing Just Happens After Another 243 REPLY TO TED HONDERICH 271 lO. Tscha Hung: Ayer and the Vienna Circle 279 REPLY TO TSCHA HUNG 301 1l. Peter Kivy: Oh Boy! You Too!: Aesthetic Emotivism Reexamined 309 REPLY TO PETER KIVY 326 12. Arne Naess: Ayer on Metaphysics, a Critical Commentary by a Kind of Metaphysician 329 REPLY TO ARNE NAESS 341 13. D.J. O'Connor: Ayer on Free Will and Determinism 347 REPLY TO D.J. -

SAKAE KUBO Honderich, Ted. How Free Are You? the Determinism

BOOK REVIEWS 123 set forth his own view of the "center" without giving equal space to others. An article which sets forth differing views should not be written by a person who represents one of these views. Or if the author is a protagonist for one of the views under discussion, he or she should at least avoid setting forth hidher own view as unquestionably the best. In light of the editors' remarks in the preface, it is difficult to understand how P. W. Barnett could write his article on the "Opponents of Paul" without any reference to Sanders's view. Sanders is neither mentioned in the article nor listed in the bibliography. Whether Sanders is correct or not is not the issue. There is nothing wrong with Barnett's view that most of Paul's opponents were Judaizers, but at least he should state why he takes this position in light of Sanders's challenge to this view. The cross-referencing of all the articles is a welcome feature that considerably heightens the volume's usefulness. The work also includes a Pauline letter index, a subject index, and an article index. On format, it would have been much easier to locate the end of each article if the word BIBLIOGRAPHY had been laced in bold print with space between it and the cross references. A few typographical errors were noted. The word "human" is repeated (877, col. 2, para. I), and "Moreover" (673) and "condemns" (942) are misspelled. Especially because of the timeliness of the volume it will serve as a handy reference to check where evangelicals stand with regard to recent Pauline studies. -

Nkrumah and Hountondji on Ethno-Philosophy a Critical Appraisal

NKRUMAH AND HOUNTONDJI ON ETHNO-PHILOSOPHY A CRITICAL APPRAISAL Martin Odei Ajei (Ghana) 1. Introduction Today, ‘African philosophy’ is well understood as a culturally determined specifi cation of philosophy comprising both oral and written traditions of speculative and analytical thought1. Th is consensus on the nature and pos- sibility conditions of this type of philosophy was achieved by considerable debate in which the term ‘ethno-philosophy’ was a most contested notion. Th e term was introduced to philosophical vocabulary by Kwame Nkrumah in the title of an uncompleted2 thesis entitled Mind and Th ought in primi- tive Society: A Study in Ethno-philosophy, which was intended for partial fulfi llment of the award of a PhD degree3. Henceforth, this work will be rendered as ‘the thesis’. 1 Wiredu, K. 1995, “African Philosophy”, in Ted Honderich (ed.), Th e Oxford Companion to Philoso- phy, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 17-18. 2 Professor Hountondji, in an email correspondence with me dated 22 August 2010, expressed the opinion that the thesis is perhaps not well described as “uncompleted” because “it seems to be quite complete as it is”. Although this is a fair judgment of the state of the work, I maintain the description as uncompleted for this reason: as mentioned in the footnote above, Nkrumah confi rms going to England with the aim of completing his thesis in ethno-philosophy. He does not indicate elsewhere that the work was actually completed. Th erefore I consider it is safer to describe it as “uncompleted”. 3 Th e most probable period for the composition of this work is between 1943 and 1945, at the earliest. -

Alfred Jules Ayer (1910-1989) Ambition

A.J. Ayer (1910-1989) 83 ing, gave Richard Wollheim space on its front page to praise Ayer as a ehituarp philosopherand intellectual. After calling him "one ofthe foremost philos ophers ofhis day" he proceeded to describe the sort ofphilosopher he was: As significant as Ayer's philosophy was the kind of philosopher that he was. Fundamentally he believed that philosophy was a profound part of human culture. In this way he was an intellectual in the European sense. But he thought that the diffusion ofphilosophy did not require a diminution either in rigour or in Alfred Jules Ayer (1910-1989) ambition. No philosophical view, he always thought, was worth more than the by John G. Slater arguments that could be brought fOlWard in its favour. And no philosophical view could beofinterest unless it could be generalized into a principle. In his obituary in the same newspaper John Foster led off by saying that A.I. Ayer was the most important British philosopher ofhis generation. Indeed, I HAPPENED TO bein London on 27 June 1989 when A.J. Ayerdied, and among twentieth-century British philosophers, he ranks second only to Russell. I made a point of collecting the obituaries that were published in the newspapers.· As I expected, there was quite a splash of publicity: BBC That remark would have pleased Ayer, since he ended the first volume of Radio assembled a panel of his friends to discuss his life and work, and his autobiography, Part ofMy Life, which took him up to his thirty-fifth most of the serious newspapers announced his death on their front pages. -

The Oberlin Colloquium in Philosophy: Program History

The Oberlin Colloquium in Philosophy: Program History 1960 FIRST COLLOQUIUM Wilfrid Sellars, "On Looking at Something and Seeing it" Ronald Hepburn, "God and Ambiguity" Comments: Dennis O'Brien Kurt Baier, "Itching and Scratching" Comments: David Falk/Bruce Aune Annette Baier, "Motives" Comments: Jerome Schneewind 1961 SECOND COLLOQUIUM W.D. Falk, "Hegel, Hare and the Existential Malady" Richard Cartwright, "Propositions" Comments: Ruth Barcan Marcus D.A.T. Casking, "Avowals" Comments: Martin Lean Zeno Vendler, "Consequences, Effects and Results" Comments: William Dray/Sylvan Bromberger PUBLISHED: Analytical Philosophy, First Series, R.J. Butler (ed.), Oxford, Blackwell's, 1962. 1962 THIRD COLLOQUIUM C.J. Warnock, "Truth" Arthur Prior, "Some Exercises in Epistemic Logic" Newton Garver, "Criteria" Comments: Carl Ginet/Paul Ziff Hector-Neri Castenada, "The Private Language Argument" Comments: Vere Chappell/James Thomson John Searle, "Meaning and Speech Acts" Comments: Paul Benacerraf/Zeno Vendler PUBLISHED: Knowledge and Experience, C.D. Rollins (ed.), University of Pittsburgh Press, 1964. 1963 FOURTH COLLOQUIUM Michael Scriven, "Insanity" Frederick Will, "The Preferability of Probable Beliefs" Norman Malcolm, "Criteria" Comments: Peter Geach/George Pitcher Terrence Penelhum, "Pleasure and Falsity" Comments: William Kennick/Arnold Isenberg 1964 FIFTH COLLOQUIUM Stephen Korner, "Some Remarks on Deductivism" J.J.C. Smart, "Nonsense" Joel Feinberg, "Causing Voluntary Actions" Comments: Keith Donnellan/Keith Lehrer Nicholas Rescher, "Evaluative Metaphysics" Comments: Lewis W. Beck/Thomas E. Patton Herbert Hochberg, "Qualities" Comments: Richard Severens/J.M. Shorter PUBLISHED: Metaphysics and Explanation, W.H. Capitan and D.D. Merrill (eds.), University of Pittsburgh Press, 1966. 1965 SIXTH COLLOQUIUM Patrick Nowell-Smith, "Acts and Locutions" George Nakhnikian, "St. Anselm's Four Ontological Arguments" Hilary Putnam, "Psychological Predicates" Comments: Bruce Aune/U.T. -

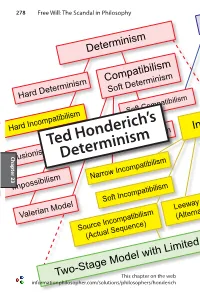

Ted Honderich's Determinism

278 Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy Determinism Indeterminism Hard Determinism Compatibilism Libertarianism Soft Determinism Hard Incompatibilism Soft Compatibilism Event-Causal Agent-Causal Chapter 23 Chapter Ted Honderich’s Illusionism DeterminismSemicompatibilism Incompatibilism SFA Non-Causal Impossibilism Narrow Incompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Causality Valerian Model Soft Incompatibilism Modest Libertarianism Soft Libertarianism Source Incompatibilism Leeway Incompatibilism Cogito Daring Soft Libertarianism (Actual Sequence) (Alternative Sequences) informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/honderichTwo-Stage Model with Limited Determinism and Limited Indeterminism This chapter on the web Ted Honderich 279 Indeterminism Ted Honderich’s Determinism DeterminismLibertarianism Ted Honderich is the principal spokesman for strict physical causality and “hard determinism.” Agent-Causal He has written more widely (with excursions into quantum Compatibilism mechanics,Event-Causal neuroscience, and consciousness), more deeply, and Soft Determinism certainly more extensively than most of his colleagues on the Hard Determinism problem of free will. Unlike most of his determinist colleagues specializingNon-Causal in free will, Honderich has notSFA succumbed to the easy path of Soft Compatibilism compatibilism by simply declaring that the free will we have (and should want, says Daniel Dennett) is completely consistent Hard Incompatibilism Incompatibilismwith determinism, namely a HumeanSoft “voluntarism” Causality or “freedom -

Ted Honderich

2 also published by OXFORD UNIVerSITY PreSS The Opacity of Mind An Integrative Theory of Self-Knowledge Peter Carruthers Explaining the Brain Mechanisms and the Mosaic Unity of Neuroscience What is it for you to be conscious? There is no agreement whatever in philosophy or science: Carl F. Craver it has remained a hard problem, a mystery. Is this partly or mainly owed to the existing honderich theories not even having the same subject, not answering the same question? In Actual TED HONDERICH, Grote Professor The Character of Consciousness Consciousness, Ted Honderich sets out to supersede dualisms, objective physicalisms, abstract Emeritus of the Philosophy of Mind and Logic David J. Chalmers functionalism, externalisms, and all other theories. He argues that the theory of Actualism, at University College London, past chairman of right or wrong, is unprecedented, in nine ways. (1) It begins from a gathered database and the Royal Institute of Philosophy, and visiting Subjective Consciousness proceeds to an adequate initial clarification of consciousness in the primary ordinary sense. professor at Yale and the CUNY Graduate A Self-Representational Theory This consciousness is summed up as something’s being actual. (2) Like basic science, Actualism Centre, came to England from Canada as a Uriah Kriegel proceeds from this metaphorical or figurative beginning to what is wholly literal and explicit— graduate student. He has lived in London for Actual Actual constructed answers to the questions of what is actual and what it is for it to be actual. (3) In most of his life, and lectured in much of Europe so doing, the theory respects the differences of consciousness within perception, consciousness and the East. -

Comment on Ted Honderich's 'Radical Externalism'

Comment on Ted Honderich’s ‘Radical Externalism’ Tim Crane Department of Philosophy, UCL Ted Honderich’s theory of consciousness as existence, which he here calls radical externalism, starts with a good phenomenological observation: that perceptual experience appears to involve external things being immediately present to us. As P.F. Strawson once observed, when asked to describe my current perceptual state, it is normally enough simply to describe the things around me (Strawson 1979: 97). But in my view that does not make the whole theory plausible. There are puzzling questions one can raise about the theory – for example: how can a conscious desire for X, or the imagination of X simply consist in the existence of X ‘in a way’? How can this model of consciousness be extended to bodily sensations? What has to exist ‘in a way’ for a sensation of nausea to exist? But in this brief note I will focus on what are to me three outstanding weaknesses in Honderich’s present paper: the formulation of his theory, his treatment of the most obvious problem for the theory, and his criticisms of opposing views. Radical externalism is ‘the general proposition that what it is to be perceptually conscious is for a world in a way to exist -- i.e. for things to be in space and time with certain properties’. So to be conscious of reading this page simply is for the page to exist ‘in a way’, or to ‘be there’. Call the state of affairs of the page existing, ‘S’. Is the idea that the existence of S suffices for you to be conscious of it? Honderich equivocates. -

After the Terror (Expanded and Revised Edition) by Ted Honderich, Edinburgh University Press, 2003, 188 Pp

After the Terror (Expanded and Revised Edition) by Ted Honderich, Edinburgh University Press, 2003, 188 pp. Jon Pike This book is by Ted Honderich, the former Grote Professor of Logic at University College, London. It comes with a history – and, in this edition, it comes revised and with an ‘unrueful postscript.’ This is a shame, because Honderich should be just a little rueful about this book. He should be rueful because the book ought to have done very serious damage to his reputation as one of Britain’s leading philosophers. Essentially, there are two parts to the argument of the book. The first part concerns world poverty. Honderich outlines a deep criticism of world poverty, and places a great deal of emphasis on the reach and significance of this criticism. Drawing on some obviously shocking figures concerning life expectancy, income and income distribution in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Sierra Leone, Honderich reports and condemns the half-lives and quarter-lives that stand in shocking contrast to those in the affluent West. His explanation for this lies largely with the omissions of those in the West. Honderich denies any moral relevance, when designating the rightness and wrongness of acts, to the distinction between acts and omissions – between what we actively do, and what we fail to do. He explains, ‘My not giving the $1200 to Oxfam, which is definitely something I do, and something bound up with giving it to the airline, has the effect of some lives being lost, the same effect as the possible action of ordering your armed forces to stop the food convoys getting through for a while’ (p. -

THE DETERMINISM and FREEDOM PHILOSOPHY WEBSITE Edited by Ted Honderich

620pixeltable Page 1 of 5 THE DETERMINISM AND FREEDOM PHILOSOPHY WEBSITE edited by Ted Honderich INTRODUCTION AND INDEX On offer here eventually will be a good selection of the most important pieces of writing on the various subjects in the philosophy of Determinism and Freedom. The name of this philosophy might have been Determinism and Free Will, since in this context 'free will' is often used generally to mean the same as 'freedom'. In fact there is such a philosophical custom. It is better, however, despite that disadvantage, to use the term 'free will' in a particular way, for a particular kind of freedom -- for one species included in the genus 'freedom'. This is what is also called origination. The subjects in the philosophy of Determinism and Freedom include the nature of causation, the different kind of freedom that is voluntariness rather than free will or orgination, and so on. For those who want a guide to the language of it all, some technical, try Determinism, Freedom and Free Will Philosophy -- The Terminology. Do you ask in what sense the selected and to a lesser extent the selected and the listed pieces are the 'most important'? You should. The answer is a pretty standard one, if not always made explicit. It is not easily given, and not easy to be brief about. Some things are included or listed because they are well-known or famous to philosophers generally and might be true -- true in the judgement of your guide. Some other writings, not many, are included because they might be true, necessarily again in the judgement of the guide -- without being well-known or famous. -

Utilitarianism.Pdf

Utilitarianism This is the first general overview in many years of the history and the present condition of utilitarian ethics. Unlike other introductions to the subject, which narrowly focus on the Enlightenment and Victorian eras, Utilitarianism takes a wider view. Geoffrey Scarre introduces the major utilitarian philosophers from the Chinese sage Mo Tzu in the fifth century BC through to Richard Hare in the twentieth. But Scarre not only surveys the history of the ‘doctrine of utility’; in later chapters he also enters the current debates on the viability of the theory. Utilitarianism today faces challenges on several fronts: its opponents argue that it lacks a credible theory of value, that it fails to protect the essential interests of individuals and that it denies them the space to pursue the personal concerns that give meaning to their lives. Geoffrey Scarre examines and discusses these charges, but he concludes that, despite the flaws of utilitarian theory, its positions are still relevant and significant today. Written especially with undergraduates in mind, this is an ideal course book for those studying and teaching moral philosophy. Geoffrey Scarre is Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Durham. He is the author of Logic and Reality in the Philosophy of John Stuart Mill and the editor of Children, Parents and Politics. The Problems of Philosophy Founding editor: Ted Honderich Editors: Tim Crane and Jonathan Wolff, University College London This series addresses the central problems of philosophy. Each book gives a fresh account of a particular philosophical theme by offering two perspectives on the subject: the historical context and the author’s own distinctive and original contribution. -

Language, Truth, and Logic and the Anglophone Reception of the Vienna Circle1

Language, Truth, and Logic and the Anglophone reception of the Vienna Circle1 Andreas Vrahimis (University of Cyprus) [Draft, forthcoming in Adam Tuboly (ed.), The Historical and Philosophical Significance of Ayer’s Language Truth and Logic, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.] Abstract: A. J. Ayer’s Language, Truth, and Logic had been responsible for introducing the Vienna Circle’s ideas, developed within a Germanophone framework, to an Anglophone readership. Inevitably, this migration from one context to another resulted in the alteration of some of the concepts being transmitted. Such alterations have served to facilitate a number of false impressions of Logical Empiricism from which recent scholarship still tries to recover. In this paper, I will attempt to point to the ways in which LTL has helped to foster the various mistaken stereotypes about Logical Empiricism which were combined into the received view. I will begin by examining Ayer’s all too brief presentation of an Anglocentric lineage for his ideas. This lineage, as we shall see, simply omits the major 19th century Germanophone influences on the rise of analytic philosophy. The Germanophone ideas he presents are selectively introduced into an Anglophone context, and directed towards various concerns that arose within that context. I will focus on the differences between Carnap’s version of the overcoming of metaphysics, and Ayer’s reconfiguration into what he calls the elimination of metaphysics. Having discussed the above, I will very briefly outline the consequences that Ayer’s radicalisation of the Vienna Circle’s doctrines had on the subsequent Anglophone reception of Logical Empiricism. 1. Introduction In the somewhat apologetic introduction to the second edition of Language, Truth, and Logic (LTL), published a decade after the first edition in 1946, A.