Glencore Xstrata – the Birth of a Mining Monster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BHP Economic Contribution Report 2017 1 Chief Financial Officer’S Introduction

Economic Contribution Report 2017 We have a long-standing commitment to transparency. We are proud of the value we generate and how this contributes to building trust with the communities in which we operate. In this Report Chief Financial Officer’s Introduction 2 Tax and our 2017 Financial Statements 20 FY2017 Total economic contribution 3 Basis of Report preparation 21 Our contribution throughout the value chain 6 Glossary 22 Approach to transparency and tax 9 Independent auditor’s report to the Directors Our payments to governments 14 of BHP Billiton Plc and BHP Billiton Limited 23 Corporate Directory 24 BHP Billiton Limited. ABN 49 004 028 077. Registered in Australia. Registered office: 171 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia. BHP Billiton Plc. Registration number 3196209. Registered in England and Wales. Registered office: Nova South, 160 Victoria Street London SW1E 5LB United Kingdom. Each of BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc is a member of the Group, which has its headquarters in Australia. BHP is a Dual Listed Company structure comprising BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc. The two entities continue to exist as separate companies but operate as a combined Group known as BHP. The headquarters of BHP Billiton Limited and the global headquarters of the combined Group are located in Melbourne, Australia. The headquarters of BHP Billiton Plc are located in London, United Kingdom. Both companies have identical Boards of Directors and are run by a unified management team. Throughout this publication, the Boards are referred to collectively as the Board. Shareholders in each company have equivalent economic and voting rights in the Group as a whole. -

The Profitable and Untethered March to Global Resource Dominance!

Athens Journal of Business and Economics X Y GlencoreXstrata… The Profitable and Untethered March to Global Resource Dominance! By Nina Aversano Titos Ritsatos† Motivated by the economic causes and effects of their merger in 2013, we study the expansion strategy deployment of Glencore International plc. and Xstrata plc., before and after their merger. While both companies went through a series of international acquisitions during the last decade, their merger is strengthening effective vertical integration in critical resource and commodity markets, following Hymer’s theory of internationalization and Dunning’s theory of Eclectic Paradigm. Private existence of global dominant positioning in vital resource markets, posits economic sustainability and social fairness questions on an international scale. Glencore is alleged to have used unethical business tactics, increasing corruption, tax evasion and money laundering, while attracting the attention of human rights organizations. Since the announcement of their intended merger, the company’s market performance has been lower than its benchmark index. Glencore’s and Xstrata’s economic success came from operating effectively and efficiently in markets that scare off risk-averse companies. The new GlencoreXstrata is not the same company anymore. The Company’s new capital structure is characterized by controlling presence of institutional investors, creating adherence to corporate governance and increased monitoring and transparency. Furthermore, when multinational corporations like GlencoreXstrata increase in size attracting the attention of global regulation, they are forced by institutional monitoring to increase social consciousness. When ensuring full commitment to social consciousness acting with utmost concern with regard to their commitment by upholding rules and regulations of their home or host country, they have but to become “quasi-utilities” for the global industry. -

Empirical Inference of Related Trading Between Two Securities: Detecting Pairs Trading, Merger Arbitrage, and Strategy Rules*

Empirical inference of related trading between two securities: Detecting pairs trading, merger arbitrage, and strategy rules* Keith Godfrey The University of Western Australia Working paper: 5 September 2013 The traditional approach to studying pairs trading is to simulate profitability using ex-post historical prices. I study the actual trades reported anonymously in security pairs and build statistical inferences of related trading. The approach is based on the time differences between trades. It can distinguish intrinsically related securities from pseudo-random sets, find stocks involved in merger arbitrage in massive sets of paired index constituents, and infer dominant trading rules of mean reversion algorithms. Empirical inference of related trading can enable further studies into pairs trading, strategy rules, merger arbitrage, and insider trading. Keywords: Inferred trading, empirical inference, pairs trading, merger arbitrage. JEL Classification Codes: G00, G10, C10, C40, C60 The availability of intraday trading or “tick” data with time resolution of a millisecond or finer is opening many avenues of research into financial markets. Analysis of two or more streams of tick data concurrently is becoming increasingly important in the study of multiple-security trading including index tracking, pairs trading, merger arbitrage, and market-neutral strategies. One of the greatest challenges in empirical trading research is the anonymity of reported trades. Securities exchanges report the dates, times, prices, and volumes traded, without identifying the traders. In studies of a single security, this introduces uncertainty of whether each market order that caused a trade was the buy or sell order, and there are documented approaches of inference such as Lee and Ready (1991). -

BP and Rio Tinto Plan Clean Coal Project for Western Australia I P

BP and Rio Tinto Plan Clean Coal Project for Western Australia I p... http://www.bp.com/genericarticle.do?categoryId=2012968&content... Site Index | Contact us | Reports and publications | BP worldwide | Home Search: Go About BP Environment and society Products and services Investors Press Careers BP Global Press Press releases Press releases BP and Rio Tinto Plan Clean Coal Project for Western Speeches Australia Features and news Images and graphics Release date: 21 May 2007 Contact Information In this section BP and Rio Tinto today announced that they are beginning feasibility studies and work on plans for the potential BP Takes Delivery of development of a A$2 billion (US$1.5 billion) coal-fired World's Largest LNG Carrier power generation project at Kwinana in Western Australia What is RSS? BP and D1 Oils Form Joint that would be fully integrated with carbon capture and Venture to Develop Jatropha storage to reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases. This Biodiesel Feedstock will be the first new project for Hydrogen Energy, the new BP Announces Significant company launched by BP and Rio Tinto last week, subject North Sea Investment to Boost to regulatory approval. The planned project would be an UK Gas Supplies industrial-scale coal-fired power and carbon capture and storage project. It would generate enough electricity to BP, ABF and DuPont Unveil $400 Million Investment in UK meet 15 per cent of the demand of south west Western Biofuels Australia, while each year capturing and permanently storing about four million tonnes of carbon dioxide which BP and TNK-BP Plan otherwise would have been emitted to the atmosphere.The Strategic Alliance with project would gasify locally-produced coal from the Collie Gazprom as TNK-BP Sells its region to produce hydrogen and carbon dioxide. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2016 Introduction

ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2016 INTRODUCTION Antofagasta is a Chilean copper mining group with signifi cant by-product production and interests in transport. The Group creates value for its stakeholders through the discovery, development and operation of copper mining assets. The Group is committed to generating value in a safe and sustainable way throughout the commodity cycle. See page 2 for more information CONTENTS STRATEGIC REPORT GOVERNANCE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 01-05 66-119 120-187 OVERVIEW 2016 highlights 1 Leadership Independent auditors’ report 122 At a glance 2 Chairman’s Governance Q&A 68 Consolidated income statement 127 Letter from the Chairman 4 Senior Independent Director’s Q&A 70 Consolidated statement Governance overview 71 of comprehensive income 128 Board of Directors 72 Consolidated statement of Executive Committee 76 changes in equity 128 06-27 Effectiveness Consolidated balance sheet 129 STRATEGY Board activities 78 Consolidated cash flow statement 130 Professional development 80 Notes to the financial statements 131 Effectiveness reviews 82 Parent company financial statements 181 Statement from the CEO 8 Accountability Question and answer 9 Nomination and Governance Committee 85 Investment case 10 Audit and Risk Committee 88 Our new operating model 11 Sustainability and Stakeholder Our position in the market 14 188-204 Management Committee 92 Our strategy 16 OTHER INFORMATION Projects Committee 94 Key performance indicators 18 Remuneration Risk management 20 Five year summary 188 Committee Chairman’s Principal -

Preparing for Carbon Pricing: Case Studies from Company Experience

TECHNICAL NOTE 9 | JANUARY 2015 Preparing for Carbon Pricing Case Studies from Company Experience: Royal Dutch Shell, Rio Tinto, and Pacific Gas and Electric Company Acknowledgments and Methodology This Technical Note was prepared for the PMR Secretariat by Janet Peace, Tim Juliani, Anthony Mansell, and Jason Ye (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions—C2ES), with input and supervision from Pierre Guigon and Sarah Moyer (PMR Secretariat). The note comprises case studies with three companies: Royal Dutch Shell, Rio Tinto, and Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E). All three have operated in jurisdictions where carbon emissions are regulated. This note captures their experiences and lessons learned preparing for and operating under policies that price carbon emissions. The following information sources were used during the research for these case studies: 1. Interviews conducted between February and October 2014 with current and former employees who had first-hand knowledge of these companies’ activities related to preparing for and operating under carbon pricing regulation. 2. Publicly available resources, including corporate sustainability reports, annual reports, and Carbon Disclosure Project responses. 3. Internal company review of the draft case studies. 4. C2ES’s history of engagement with corporations on carbon pricing policies. Early insights from this research were presented at a business-government dialogue co-hosted by the PMR, the International Finance Corporation, and the Business-PMR of the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) in Cologne, Germany, in May 2014. Feedback from that event has also been incorporated into the final version. We would like to acknowledge experts at Royal Dutch Shell, Rio Tinto, and Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E)—among whom Laurel Green, David Hone, Sue Lacey and Neil Marshman—for their collaboration and for sharing insights during the preparation of the report. -

Itraxx Europe & Crossover Series 35 Final Membership List

iTraxx Europe & Crossover Series 35 Final Membership List March 2021 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd T180614 iTraxx Europe & Crossover Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Europe Series 35 Final Membership List......................................... 3 2 iTraxx Europe Series 35 Final vs. Series 34.............................................. 7 3 iTraxx Crossover Series 35 Final Membership List ................................... 8 4 iTraxx Crossover Series 35 Final vs. Series 34........................................11 5 Further information ...................................................................................12 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 2 T180614 iTraxx Europe & Crossover Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Europe Series 35 Final Membership List iTraxx Sector IHS Markit Ticker IHS Markit Long Name Autos & Industrials AIRBSE AIRBUS SE Autos & Industrials VLVY AKTIEBOLAGET VOLVO Autos & Industrials AKZO AKZO NOBEL N.V. Autos & Industrials ALSTOM ALSTOM Autos & Industrials AAUK ANGLO AMERICAN PLC Autos & Industrials AZN ASTRAZENECA PLC Autos & Industrials BAPLC BAE SYSTEMS PLC Autos & Industrials BASFSE BASF SE Autos & Industrials BYIF BAYER AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT Autos & Industrials BMW BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT Autos & Industrials BOUY BOUYGUES Autos & Industrials CNHIND CNH INDUSTRIAL N.V. Autos & Industrials STGOBN COMPAGNIE DE SAINT-GOBAIN Autos & Industrials COMPFIAG COMPAGNIE FINANCIERE MICHELIN SA Autos & Industrials CONTI CONTINENTAL AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT Autos & Industrials DAMLR DAIMLER -

Glencore's Shares Drop After Justice Department Subpoena

WL SEIS Exhibit 9 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/business/glencore-subpoena-mining-commodities.html Glencore’s Shares Drop After Justice Department Subpoena By Stanley Reed and Michael J. de la Merced July 3, 2018 LONDON — Glencore, a Switzerland‑based mining and commodities trading giant, said on Tuesday that it had received a subpoena from the United States Department of Justice requesting documents in a money‑laundering and corruption investigation. The subpoena is tied to Glencore’s dealings in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria and Venezuela since 2007, and it seeks material related to “compliance with the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act” and with United States money‑laundering rules, the company said in a statement. News that American investigators were looking into Glencore’s businesses spooked investors, sending the company’s share price down as much as 13 percent at one point on Tuesday. By late afternoon in London, its stock price had recovered somewhat, but was still 5 percent lower. Charles Watenphul, a Glencore spokesman, said, “We got this letter last night; we are going through it.” While Glencore has not been charged with any crime, the development is a blow to one of the most powerful commodities mining and trading empires around, one that employs 146,000 workers around the world. With headquarters in Baar, near Zurich, the company is among the biggest producers of copper and of cobalt, a crucial component of batteries for electric vehicles and electronic devices like smartphones. (Cobalt is so important that the Trump administration has deemed it critical for American national security.) Glencore is also a major player in coal, with 26 mines in countries such as Australia, Colombia and South Africa. -

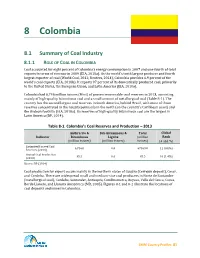

Chapter 8: Colombia

8 Colombia 8.1 Summary of Coal Industry 8.1.1 ROLE OF COAL IN COLOMBIA Coal accounted for eight percent of Colombia’s energy consumption in 2007 and one-fourth of total exports in terms of revenue in 2009 (EIA, 2010a). As the world’s tenth largest producer and fourth largest exporter of coal (World Coal, 2012; Reuters, 2014), Colombia provides 6.9 percent of the world’s coal exports (EIA, 2010b). It exports 97 percent of its domestically produced coal, primarily to the United States, the European Union, and Latin America (EIA, 2010a). Colombia had 6,746 million tonnes (Mmt) of proven recoverable coal reserves in 2013, consisting mainly of high-quality bituminous coal and a small amount of metallurgical coal (Table 8-1). The country has the second largest coal reserves in South America, behind Brazil, with most of those reserves concentrated in the Guajira peninsula in the north (on the country’s Caribbean coast) and the Andean foothills (EIA, 2010a). Its reserves of high-quality bituminous coal are the largest in Latin America (BP, 2014). Table 8-1. Colombia’s Coal Reserves and Production – 2013 Anthracite & Sub-bituminous & Total Global Indicator Bituminous Lignite (million Rank (million tonnes) (million tonnes) tonnes) (# and %) Estimated Proved Coal 6,746.0 0.0 67469.0 11 (0.8%) Reserves (2013) Annual Coal Production 85.5 0.0 85.5 10 (1.4%) (2013) Source: BP (2014) Coal production for export occurs mainly in the northern states of Guajira (Cerrejón deposit), Cesar, and Cordoba. There are widespread small and medium-size coal producers in Norte de Santander (metallurgical coal), Cordoba, Santander, Antioquia, Cundinamarca, Boyaca, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Borde Llanero, and Llanura Amazónica (MB, 2005). -

Annual Review and Summary Financial Statements 2010 Shareholder Information Continued

Centrica plc Registered office: Millstream, Maidenhead Road, Windsor, Berkshire SL4 5GD Company registered in England and Wales No. 3033654 www.centrica.com Annual Review and Summary Financial Statements 2010 Shareholder Information continued SHAREHOLDER SERVICES Centrica shareholder helpline To register for this service, please call the shareholder helpline on 0871 384 2985* to request Centrica’s shareholder register is maintained by Equiniti, a direct dividend payment form or download it from which is responsible for making dividend payments and www.centrica.com/shareholders. 01 10 updating the register. OVERVIEW SUMMARY OF OUR BUSINESS The Centrica FlexiShare service PERFORMANCE If you have any query relating to your Centrica shareholding, 01 Chairman’s Statement please contact our Registrar, Equiniti: FlexiShare is a ‘corporate nominee’, sponsored by Centrica and administered by Equiniti Financial Services Limited. It is 02 Our Performance 10 Operating Review Telephone: 0871 384 2985* a convenient way to manage your Centrica shares without 04 Chief Executive’s Review 22 Corporate Responsibility Review Textphone: 0871 384 2255* the need for a share certificate. Your share account details Write to: Equiniti, Aspect House, Spencer Road, Lancing, will be held on a separate register and you will receive an West Sussex BN99 6DA, United Kingdom annual confirmation statement. Email: [email protected] By transferring your shares into FlexiShare you will benefit from: A range of frequently asked shareholder questions is also available at www.centrica.com/shareholders. • low-cost share-dealing facilities provided by a panel of independent share dealing providers; Direct dividend payments • quicker settlement periods; Make your life easier by having your dividends paid directly into your designated bank or building society account on • no share certificates to lose; and the dividend payment date. -

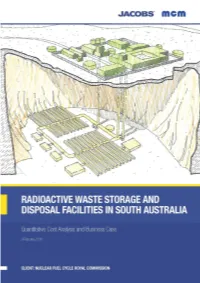

Jacobs MCM- Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Of

Radi oacti ve Waste S tor age and Dispos al F acilities in S out h A ustr alia – Quantit ati ve C ost A nal ysis and Business C as e Radioactive Waste Storage and Disposal Facilities in South Australia – Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Radioactive Waste Storage and Disposal Facilities in South Australia – Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Project no: IW104700 Document title: Radioactive Waste Storage and Disposal Facilities in South Australia – Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Revision: Draft Report V1 Date: 09 February 2016 Client name: South Australian Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission Client no: Jacobs Report (0.4) Project manager: Tim Johnson Authors: Darron Cook, Charles McCombie, Neil Chapman, Nigel Sullivan, Rohan Zauner, Tim Johnson File name: J:\IE\Projects\03_Southern\IW104700\21 Deliverables\Reformatted Docs for Client Release\09022016 Combined Papers V1.0.docx Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited ABN 37 001 024 095 Floor 11, 452 Flinders Street Melbourne VIC 3000 PO Box 312, Flinders Lane Melbourne VIC 8009 Australia T +61 3 8668 3000 F +61 3 8668 3001 www.jacobs.com COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Document history and status Revision Date Description By Review Approved V0 19 Jan 2016 For Client review Darron Darron Cook Darron Cook, team Cook V1 9 February For public consultation Tim Johnson Darron Cook Darron Cook IW104700 i Radioactive Waste Storage and Disposal Facilities in South Australia – Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. -

BHP Billiton Iron Ore Management Approach

BHP Billiton Iron Ore Orebody 32 East AWT – Environmental Referral Document BHP Billiton Iron Ore management approach 1.1 Environmental management overview BHP Billiton has developed a Company Charter and Sustainable Development Policy for its operations. The Company Charter and Sustainable Development Policy (BHP Billiton Iron Ore, 2013a) are guiding resources for maintaining an emphasis on health, safety, environment and community and clarifying a broader commitment to aspects of sustainability including biodiversity, human rights, ethical business practices and economic contributions at all BHP Billiton sites. To interpret and support the Company Charter and BHP Billiton Iron Ore’s Sustainable Development Policy, BHP Billiton Iron Ore has developed an Environmental Governance Hierarchy, an Environmental Management System and is currently developing a series of Regional Management Strategies. 1.2 Environment Governance Hierarchy BHP Billiton Iron Ore now operates under an Environmental Governance Hierarchy (Figure 1). The Environment Governance Hierarchy provides the processes and practices that enable BHP Billiton Iron Ore to achieve its environmental objectives, reduce its environmental impacts and increase its operating efficiency. It enables environmental legal compliance to be undertaken and audited and provides for continual improvement in environmental performance. Figure 1: BHP Billiton Iron Ore Environmental Governance Hierarchy As shown in Figure 1, BHP Billiton Iron Ore’s environment governance hierarchy is broadly comprised of three tiers, representative of BHP Billiton Iron Ore’s different levels of management – BHP Billiton (corporate level), BHP Billiton Iron Ore (Business Unit level) and site specific (operations level) – and reflective of BHP Billiton’s top-down approach to environmental management across the Group.