Black Studies in the Digital Crawlspace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swinging Along the Border: Charles Mingus' Album 'Tijuana Moods' Finds New Resonance

♫ Donate LOADING... On the Air Music News Listen & Connect Calendars & Events Support About Search Swinging Along the Border: Charles Mingus' Album 'Tijuana Moods' Finds New Resonance By DAVID R. ADLER • JAN 18, 2018 ! Twitter " Facebook # Google+ $ Email “All the music in this album was written during a very blue period in my life,” the bassist Charles Mingus observed in the liner notes to Tijuana Moods. Recorded a little over 60 years ago, on July 18 and August 6, 1957, it’s an album that remains unique not only in the Mingus discography but also in jazz as a whole. Less an expression of Mexican musical influence than a personal evocation of a place, the album belongs to a vibrant category of border art. At a moment of heated political debate around immigration, it strikes a deep and vital chord. And in the coming week, thanks to some resourceful programming on the west coast, Tijuana Moods is returning home. Mingus Dynasty, one of three legacy bands run by the bassist’s widow, Sue Mingus, will perform the album for the first time in Tijuana, Mexico on Sunday, in a free concert at the CECUT Cultural Center. Organizers of the concert will also present a panel discussion on Saturday at the San Diego Public Library. And the band is performing the album on a regional tour with stops in Tucson (Friday), Phoenix (Saturday), La Jolla, California (Monday) and Portland, Oregon. (Tuesday). The current Mingus Dynasty features tenor saxophonist Wayne Escoffery, alto saxophonist Brandon Wright, trumpeter Alex Sipiagin, trombonist Ku-umba Frank Lacy, pianist Theo Hill, bassist Boris Kozlov and drummer Adam Cruz. -

Jazz Music and Social Protest

Vol. 5(1), pp. 1-5, March, 2015 DOI: 10.5897/JMD2014.0030 Article Number: 5AEAC5251488 ISSN 2360-8579 Journal of Music and Dance Copyright © 2015 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JMD Full Length Research Paper Playing out loud: Jazz music and social protest Ricardo Nuno Futre Pinheiro Universidade Lusíada de Lisboa, Portugal. Received 4 September, 2014; Accepted 9 March, 2015 This article addresses the historical relationship between jazz music and political commentary. Departing from the analysis of historical recordings and bibliography, this work will examine the circumstances in which jazz musicians assumed attitudes of political and social protest through music. These attitudes resulted in the establishment of a close bond between some jazz musicians and the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s; the conceptual framing of the free jazz movement that emerged in the late 1950s and early 60s; the use on non-western musical influences by musicians such as John Coltrane; the rejection of the “entertainer” stereotype in the bebop era in the 1940s; and the ideas behind representing through music the African-American experience in the period of the Harlem Renaissance, in the 1920’s. Key words: Politics, jazz, protest, freedom, activism. INTRODUCTION Music incorporates multiple meanings 1 shaped by the supremacy that prevailed in the United States and the principles that regulate musical concepts, processes and colonial world3. products. Over the years, jazz music has carried numerous “messages” containing many attitudes and principles, playing a crucial role as an instrument of Civil rights and political messages dissemination of political viewpoints. -

Top 10 Albums Rhythm Section Players Should Listen to 1

Top 10 Albums Rhythm Section Players Should Listen To 1. Money Jungle by Duke Ellington Duke Ellington-Piano Charles Mingus-Bass Max Roach-Drums RELEASED IN 1963 Favorite Track: Caravan 2. Monk Plays Duke by Thelonious Monk Thelonious Monk- Piano Oscar Pettiford-Bass Kenny Clarke-Drums RELEASED IN 1956 Favorite Track: I Let A Song Out of My Heart 3. We Get Request by Oscar Peterson Trio Oscar Peterson-Piano Ray Brown-Bass Ed Thigpen-Drums RELEASED IN 1964 Favorite Track: Girl from Ipanema 4. Now He Sings, Now He Sobs by Chick Corea Chick Corea-Piano Miroslav Vitous-Bass Roy Haynes-Drums RELEASED IN 1968 Favorite Track: Matrix 5. We Three by Roy Haynes Phineas Newborn-Piano Paul Chambers-Bass Roy Haynes-Drums RELEASED IN 1958 Favorite Track(s): Sugar Ray & Reflections 6. Soul Station by Hank Mobley Hank Mobley-Tenor Sax Wynton Kelly-Piano Paul Chambers-Bass Art Blakey-Drums RELEASED IN 1960 Favorite Track: THE ENTIRE ALBUM! 7. Free for All by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Freddie Hubbard-Trumpet Curtis Fuller-Trombone Wayne Shorter-Tenor Saxophone Cedar Walton-Piano Reggie Workman-Bass Art Blakey-Drums RELEASED IN 1964 Favorite Track: THE ENTIRE ALBUM 8. Live at the IT Club by Thelonious Monk Charlie Rouse-Alto Saxophone Thelonious Monk-Piano Larry Gales-Bass Ben Riley-Drums RECORDED IN 1964; RELEASED IN 1988 Favorite Track: THE ENTIRE ALBUM 9. Clifford Brown & Max Roach by Clifford Brown & Max Roach Clifford Brown-Trumpet Harold Land-Tenor Saxophone Richie Powell-Piano George Morrow-Bass Max Roach-Drums RELEASED IN 1954 Favorite Track(s): Jordu, Daahoud, and Joy Spring 10. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Jazz at the Crossroads)

MUSIC 127A: 1959 (Jazz at the Crossroads) Professor Anthony Davis Rather than present a chronological account of the development of Jazz, this course will focus on the year 1959 in Jazz, a year of profound change in the music and in our society. In 1959, Jazz is at a crossroads with musicians searching for new directions after the innovations of the late 1940s’ Bebop. Musical figures such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane begin to forge a new direction in music building on their previous success earlier in the fifties. The recording Kind of Blue debuts in 1959 documenting the work of Miles Davis’ legendary sextet with John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb and reflects a new direction in the music with the introduction of a modal approach to composition and improvisation. John Coltrane records Giant Steps the culmination of the harmonic intricacies of Bebop and at the same time the beginning of something new. Ornette Coleman arrives in New York and records The Shape of Jazz to Come, an LP that presents a radical departure from the orthodoxies of Be-Bop. Dave Brubeck records Time Out, a record featuring a new approach to rhythmic structure in the music. Charles Mingus records Mingus Ah Um, establishing Mingus as a pre-eminent composer in Jazz. Bill Evans forms his trio with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian transforming the interaction and function of the rhythm section. The quiet revolution in music reflects a world that is profoundly changed. The movement for Civil Rights has begun. The Birmingham boycott and the Supreme Court decision Brown vs. -

Eddie Preston: Texas Trumpeter Fallen Through the Cracks Dave Oliphant

Eddie Preston: Texas Trumpeter Fallen Through the Cracks Dave Oliphant 8 Photo of Eddie Preston from the album Charles Mingus in Paris. Courtesy Christian Rose and Sunnyside Communications. Identifying a jazz musician’s place of birth has interested me ever since my parents gave me a copy of Leonard Feather’s 1962 The New Edition of The Encyclopedia of Jazz. Some thirty years later it became essential for me to know which musicians hailed from my home state of Texas, once I had taken on the task of writing about Texans in jazz history. As a result of this quest for knowledge, I discovered, among other things, that guitarist, trombonist, and 9 composer-arranger Eddie Durham was born and raised in San Marcos, home to Texas State University. Although I never worked my way systematically through the Feather encyclopedia or any subsequent volumes devoted to the identification of musicians’ places and dates of birth, I mistakenly felt confident that I had checked every musician on any album I had acquired over the years to see if he or she was a native Texan. Following the 1996 publication of Texan Jazz, my survey of Texas jazz musicians, I discovered a few Texans and their recordings that I had not been aware of previously. When the opportunity arose, I included them in other publications, such as my 2002 study The Early Swing Era, 1930 to 1941, and my essay “Texan Jazz, 1920- 1950,” included in The Roots of Texas Music. Despite my best efforts to trace the origins of the many jazz musicians I chronicled, it took years before I realized that Eddie Preston (a trumpeter who was born in Dallas in 1925 and died in Palm Coast, Florida, in 2009) was a native of the Lone Star State. -

Charles Mingus, Jazz and Modernism

Charles Mingus, Jazz and Modernism by: Philippe Latour Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal December 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology. © Philippe Latour 2012 Table of Content Abstracts ----------------------------------------------------------- ii Acknowledgements ----------------------------------------------------------- iv Chapter 1 ----------------------------------------------------------- 1 Introduction Chapter 2 ----------------------------------------------------------- 15 Jazz Modernism Chapter 3 ----------------------------------------------------------- 45 Mingus‟ Conception of Jazz Conclusion ----------------------------------------------------------- 63 Bibliography ----------------------------------------------------------- 66 Appendices ----------------------------------------------------------- 71 i Abstracts The purpose of this thesis is to explore the diverse discourses of modernism in jazz at mid-century in relation to the work of Charles Mingus. What was meant by modern jazz in Mingus‟ time? How was his music, as well as his life as a jazz musician and composer, affected by discourses of modernism? Modernism was used in the jazz field as a discourse to elevate jazz from its role as entertainment music into a legitimate art form. In its transfer from European art music to African-American jazz, the concept of aesthetic modernism retained most of its signification: it was associated with the notions of progress, of avant-gardism, and, eventually, of political militancy; and all these notions can be found in multiple forms in Mingus‟ work. This thesis defines the concept of modern jazz as it was used in the jazz press in the 1950s and 1960s in relation to the critical discourse around Afro-modernism as well as in relation with Mingus‟ conception of himself as a composer. L’objectif de ce mémoire est d’explorer les différents discours sur le modernisme et le jazz des années 1950 et 1960 en relation avec l’œuvre de Charles Mingus. -

Downbeat Magazine

DownBeat Magazine downbeat.com/def ault.asp Jazz Titans Lead International Jazz Day Celebration Herbie Hancock, sitting in the middle of a distinguished panel that included Marcus Miller, Robert Glasper, Al Jarreau, Terence Blanchard, T.S. Monk, John Beasley, Wayne Shorter, Lee Ritenour and John McLaughlin, stated the mission for International Jazz Day. [To use] jazz as an instrument to promote peace, encourage freedom of expression, strengthen global respect for dignity and human rights, help advance and develop a dialogue between disparate cultures, and through music education, reinforce the role of young people and their future contributions to social change, said the legendary pianist, composer and UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) Goodwill Ambassador. He reiterated those points by saying: Using jazz as a tool, I have faith that either playing an instrument, learning about its rich cultural history or listening to the millions of recordings during the past century will demonstrate that barriers can be broken. Hancock made his remarks the day before the extravagant Sunset Concert at Istanbuls Hagia Irene, a magnificent former Eastern Orthodox church- turned- museum located in the Turkish citys historic Seraglio Point. For the second annual International Jazz Day (April 30), UNESCO and its partner, the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, chose Istanbul as its host city. The transcontinental metropolis, renowned for its multifaceted cultures, religions, population and geographical location in both -

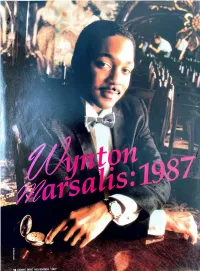

1987 DOWN BEAT 17 Melodic, Blues-Based Invention of Ornette Coleman, Or the Doing, They Weren't Interested in His Enthusiasm

By Stanley Crouch Editor's note: We last interviewed Wynton Marsalis in 1984. Since tha.t time his popularity and notoriety have, if anything, grown and, as can be seen in the following interview, he views his position with the utmost responsibility and seriousness. It is interesting to note that despite-or perhaps because of-his popularity, the trumpeter has become the focal point in a critical controversy waged over questions of innovation vs. imitation. In addressing these questions, and those concerning his success, the importance of knowledge and technical preparation for a career in music, and the role of jazz education, he brings the same carefully considered articulation which identifies his musical creativity. • • • STANLEY CROUCH: Do you hove anything to soy before we humility to one day add to the already noble tradition that first begin, on opening statement? took wing in the Crescent City. It still befuddles me that all the drums Jeff Watts is playing has been overlooked. He's isolating WYNTON MARSALIS: Yes. I want to make clear some things I aspects of time in fluctuating but cohesive parts, each of which think have been misunderstood. Were I playing the level of horn I swings, and his skill at thematic development through his aspire to, I don't think I would be giving interviews; I would be instrument within the form is nasty. But then he is The Tainish making all my statements from the bandstand. But at this point, One. Marcus Roberts is so superior in true country soul to any words allow me more precision and clarity. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Reflection of Jazz Music in American Racial Past

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Mária Takáčová Reflection of Jazz Music in American Racial Past and Present Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2016 Acknowledgement: I would like to thank my supervisor, Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A., for his kind guidance and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my family and friends for their endless support. I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. - 5 - 2. Historical Legacy ..................................................................................................... - 8 - Cry for Freedom ....................................................................................................... - 8 - Roar for Freedom ................................................................................................... - 12 - Max Roach: Freedom day .................................................................................. - 13 - Nina Simone: Mississippi Goddam ................................................................... - 14 - John Coltrane: Alabama ..................................................................................... - 18 - Charles Mingus: Fables of Faubus .................................................................... -

Charles Mingus Mingus Mp3, Flac, Wma

Charles Mingus Mingus mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Mingus Country: US Released: 1972 Style: Hard Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1812 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1486 mb WMA version RAR size: 1350 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 371 Other Formats: XM ADX MP4 MMF AHX DTS MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits MDM A1 19:52 Composed By – Mingus* Stormy Weather B1 13:25 Written-By – Arlen*, Koehler* Lock 'Em Up B2 6:35 Composed By – Mingus* Companies, etc. Recorded At – Nola Recording Studios Phonographic Copyright (p) – Phonoco Copyright (c) – Phonoco Credits Alto Saxophone – Charlie McPherson* (tracks: A, B2), Eric Dolphy Bass Clarinet – Eric Dolphy (tracks: A) Design, Photography – Frank Gauna Double Bass – Charles Mingus Drums – Dannie Richmond Engineer – Bob D'Orleans Liner Notes, Supervised By – Nat Hentoff Piano – Nico Bunick* (tracks: A), Paul Bley (tracks: B2) Tenor Saxophone – Booker Ervin (tracks: A, B2) Trombone – Britt Woodman (tracks: A), Jimmy Knepper (tracks: A) Trumpet – Lonnie Hillyer (tracks: A1, B2), Ted Curson Notes All tracks were recorded at Nola Penthouse Sound Studios, New York, on October 20, 1960 (tracks A, B1) and on November 11, 1960 (track B2). This reissue © ℗ Phonoco 1985. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Charles Candid, 9021, CS 9021 Mingus (LP, Album) 9021, CS 9021 US 1960 Mingus Candid Charles Mingus (LP, RE, DOL920H DOL DOL920H Europe 2017 Mingus 180) Charles JAZ-5002 Mingus (LP, RE) Jazz Man JAZ-5002 US 1980 Mingus Charles Mingus (CD, KICJ 8372 Candid KICJ 8372 -

Blue Notes and Brown Skin: Five African-American Jazzmen and the Music They Produced in Regard to the American Civil Rights Movement

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2005 Blue Notes and Brown Skin: Five African-American Jazzmen and the Music They Produced in Regard to the American Civil Rights Movement Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, History Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Blue Notes and Brown Skin: Five African-American Jazzmen and the Music They Produced in Regard to the American Civil Rights Movement" (2005). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626478. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-9ab3-4z88 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLUE NOTES AND BROWN SKIN Five African-American Jazzmen and the Music they Produced in Regard to the American Civil Rights Movement. A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Benjamin Park Anderson 2005 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts imin Park Anderson Approved by the Committee, May 2005 Dr. Arthur Knight, Chair Ids McGovern . Lewis Porter, Rutgers University, outside reader ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements iv List of Illustrations V List of Musical Examples vi Abstract vii Introduction 2 Chapter I.