Delhi City Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Base Map of Assembly Constituency

BASE MAP OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY - 38 / DELHI CANTT E E izfrcaf/kr dsoy foHkkxh; Á;®x gsrq RESTRICTED FOR DEPARTMENTAL USE ONLY fu;kZr ds fy, ugha NOT FOR EXPORT =(: µ M A H A T M (: A = G A N D H I M A K R G R I N G R O . A D K INDEX MAP MCD WARD NO- CANT_1, DELHI CANTT CHARGE 1 SH ANKA R LAL GALI DR-17 K TODAPUR 1 7 K 2 5 Kendriya 4 70 6 13 69 Vidyalaya 14 No.3 68 RESTRICTED 8 3 CA 9 18 66 MP 10 12 67 BE 17 63 LL AREA R 15 16 OA 65 64 D 11 62 19 20 61 26 25 24 23 22 60 27 59 31 29 21 MCD WARD NO- CANT_2, 39 KIRBY 28 58 PLACE 32 30 56 DELHI CANTONMENT DELHI CANTT 40 41 57 RAILWAY STATION 33 I2 37 55 CHARGE 2 35 38 38 0 BRAR 42 SQUARE 44 6 -1 34 51 R 43 D 4 50 - Cantonment 36 R 54 CA D Board Sr. RIA PP Sec. School K A M 45 52 AR 48 G S TA TI ON 53 RO 49 AD CHANDAN 47 HOS ROAD PITAL AL SINGH PARK RO SPIT AD HO HO SP ITA NANGAL L R OAD RING ROAD P S AD AN ER RO K -19 V COLONY 46 A HA DR IC KH R 20 E AN OA DR- LA P D NE DIPLOMATIC D P A Cantonment AN ENCLAVE K CHANDAN O G K P HA R Board Sec. -

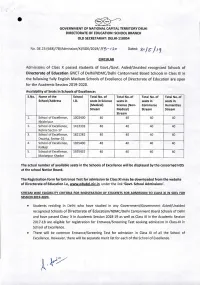

Registration of Students for Admission to Class XI in Schools Of

• GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY DELHI DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION: SCHOOL BRANCH OLD SECRETARIAT: DELHI-110054 No. DE.23 (648)/78/Admission/Xl/S0E/2019/ f 15-- .2o Dated: 30)6"--) / CIRCULAR Admissions of Class X passed students of Govt./Govt. Aided/Unaided recognized Schools of Directorate of Education GNCT of Delhi/NDMC/Delhi Cantonment Board Schools in Class XI in the following fully English Medium Schools of Excellence of Directorate of Education are open for the Academic Session 2019-2020. Availability of Seats in Schools of Excellence: S.No. Name of the School Total No. of Total No. of Total No. of Total No. of School/Address I.D. seats in Science seats in seats in seats in (Medical) Science (Non- Commerce Humanities Stream Medical) Stream Stream Stream 1. School of Excellence, 1002400 40 40 40 40 Khichripur 2. School of Excellence, 1413333 40 40 40 40 Rohini Sector-17 3. School of Excellence, 1821282 40 40 40 40 Dwarka, Sector-22 4. School of Excellence, 1925430 40 40 40 40 Kalkaji 5. School of Excellence, 1925432 40 40 40 40 Madanpur Khadar The actual number of available seats in the Schools of Excellence will be displayed by the concerned HOS at the school Notice Board. The Registration form for Entrance Test for admission to Class XI may be downloaded from the website of Directorate of Education i.e, www.edudel.nic.in under the link 'Govt. School Admissions'. STREAM WISE ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR REGISTRATION OF STUDENTS FOR ADMISSION TO CLASS XI IN SOEs FOR SESSION 2019-2020. • Students residing in Delhi who have studied in any Government/Government Aided/Unaided recognized Schools of Directorate of Education/NDMC/Delhi Cantonment Board Schools of Delhi and have passed Class- X in Academic Session 2018-19 as well as Class IX in the Academic Session 2017-18 are eligible for registration for Entrance/Screening Test seeking admission in Class-XI in School of Excellence. -

List of Containment Zone in Delhi (16-07-2020)

List of containment zone in Delhi (16-07-2020) S.NO District Containment Zone 1 South District 1.) Hauzrani 2 South District 2) Safdarjung Enclave 3 South District 3) Chirag Delhi 4 South District 4) SAVITRI NAGAR 5 South District 5) HAUZRANI EXTENDED 6 South District 6)Khirki Extension , shop no. J-4/49,khirki village 7 South District 7) Dakshinpuri H. No. F-306 to F-379 8 South District 8) Zamroodpur, Main road to 64c, from 90 c to 64 C 9 South District 9) House no. 268/D, 28, Ward No. 2, Mehrauli 10 South District 10) Maa Durga Apartments Ward No. 3 Mehrauli 11 South District 11) Affected area around H.no- B-258,B-822, C-98, H1-51 and H-16 JJ COLONY TIGRI 12 South District 12) H.NO-C-1658, C 1659, A-310 JJ COLONY TIGRI 13 South District L, L-1 and L-2 Sangam Vihar 14 South District Affected area around H.no. A86, B99, B22 226, D276, Ambedkar Colony, behind Chattarpur Mandir 15 South District H. N0. F713, Lado Sarai, New Delhi 16 South District Gali no 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12, G block Sangam Vihar 17 South District Khidki Extention : J-3/40 UPTO J-4/80 C 18 South District Malviya Nagar: M46B upto M56B 19 South District Shivalik : A-30 UPTO A-50 20 South District Dakshinpuri: H.no. 17/1 to 17/30 21 South District Dakshinpuri: H.no. 15/80 to 15/100 22 South District Madangir: H 1st full lane covering houses 200 to 250 23 South District Gali no 3,4,5 B Block SangamVihar 24 South District Affected area around H.No. -

Government Cvcs for Covid Vaccination for 18 Years+ Population

S.No. District Name CVC Name 1 Central Delhi Anglo Arabic SeniorAjmeri Gate 2 Central Delhi Aruna Asaf Ali Hospital DH 3 Central Delhi Balak Ram Hospital 4 Central Delhi Burari Hospital 5 Central Delhi CGHS CG Road PHC 6 Central Delhi CGHS Dev Nagar PHC 7 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Minto Road PHC 8 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Subzi Mandi 9 Central Delhi CGHS Paharganj PHC 10 Central Delhi CGHS Pusa Road PHC 11 Central Delhi Dr. N.C. Joshi Hospital 12 Central Delhi ESI Chuna Mandi Paharganj PHC 13 Central Delhi ESI Dispensary Shastri Nagar 14 Central Delhi G.B.Pant Hospital DH 15 Central Delhi GBSSS KAMLA MARKET 16 Central Delhi GBSSS Ramjas Lane Karol Bagh 17 Central Delhi GBSSS SHAKTI NAGAR 18 Central Delhi GGSS DEPUTY GANJ 19 Central Delhi Girdhari Lal 20 Central Delhi GSBV BURARI 21 Central Delhi Hindu Rao Hosl DH 22 Central Delhi Kasturba Hospital DH 23 Central Delhi Lady Reading Health School PHC 24 Central Delhi Lala Duli Chand Polyclinic 25 Central Delhi LNJP Hospital DH 26 Central Delhi MAIDS 27 Central Delhi MAMC 28 Central Delhi MCD PRI. SCHOOl TRUKMAAN GATE 29 Central Delhi MCD SCHOOL ARUNA NAGAR 30 Central Delhi MCW Bagh Kare Khan PHC 31 Central Delhi MCW Burari PHC 32 Central Delhi MCW Ghanta Ghar PHC 33 Central Delhi MCW Kanchan Puri PHC 34 Central Delhi MCW Nabi Karim PHC 35 Central Delhi MCW Old Rajinder Nagar PHC 36 Central Delhi MH Kamla Nehru CHC 37 Central Delhi MH Shakti Nagar CHC 38 Central Delhi NIGAM PRATIBHA V KAMLA NAGAR 39 Central Delhi Polyclinic Timarpur PHC 40 Central Delhi S.S Jain KP Chandani Chowk 41 Central Delhi S.S.V Burari Polyclinic 42 Central Delhi SalwanSr Sec Sch. -

School Schedule

DELHI COMMISSION FOR PROTECTION OF CHILD RIGHTS Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi 5th Floor, ISBT Building, Kashmiri Gate, Delhi-110006 Helpline No. -9205893636/9205893603 Email- [email protected] / [email protected] C/RTE/DCPCR/17-18/85 Dated: 08.04.2019 Under Section 31(1) of the Right of Children to Fr ee and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009 Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights is empowered to monitor the implementation of the Right to Education Act in schools (Government, aided and unaided). Therefore, subsequent to the responsibility cas t upon this Commission, the Commission is undertaking a comprehensive school evaluation exercise for all school (Directorate of Education, South Delhi Municipal Corporation, North Delhi Municipal Corporation, East Delhi Municipal Corporation and New Delhi Municipal Council) in Delhi called as School Development Index (SDI). The School Development Index will assist your school and our government collectively in improving schools so that we can ensure quality education for our children. A necessary precursor to this is a detailed data collection for which a team of assessors is being sent to your school. The team of assessors will collect information about school through different methods. Therefore following schools are to be visited from 10th April to 26th April, 2019 Note: The following list and dates are tentative and the actual dates may vary. List of Aided Schools to be visited from 10th April to 26th April, 2019 School ID School Name District 1001144 Jain Sec. School, Shahadara, Gali Jain Mandir, Delhi East 1001145 Sanatan Dharam Sr. Sec. School, Shahadara, Delhi East 1001146 Lalita PD Girls Sr. -

LIST of ORDINARY MEMBERS S.No

LIST OF ORDINARY MEMBERS S.No. MemNo MName Address City_Location State PIN PhoneMob F - 42 , PREET VIHAR 1 A000010 VISHWA NATH AGGARWAL VIKAS MARG DELHI 110092 98100117950 2 A000032 AKASH LAL 1196, Sector-A, Pocket-B, VASANT KUNJ NEW DELHI 110070 9350872150 3 A000063 SATYA PARKASH ARORA 43, SIDDHARTA ENCLAVE MAHARANI BAGH NEW DELHI 110014 9810805137 4 A000066 AKHTIARI LAL S-435 FIRST FLOOR G K-II NEW DELHI 110048 9811046862 5 A000082 P.N. ARORA W-71 GREATER KAILASH-II NEW DELHI 110048 9810045651 6 A000088 RAMESH C. ANAND ANAND BHAWAN 5/20 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI 110008 9811031076 7 A000098 PRAMOD ARORA A-12/2, 2ND FLOOR, RANA PRATAP BAGH DELHI 110007 9810015876 8 A000101 AMRIK SINGH A-99, BEHIND LAXMI BAI COLLEGE ASHOK VIHAR-III NEW DELHI 110052 9811066073 9 A000102 DHAN RAJ ARORA M/S D.R. ARORA & C0, 19-A ANSARI ROAD NEW DELHI 110002 9313592494 10 A000108 TARLOK SINGH ANAND C-21, SOUTH EXTENSION, PART II NEW DELHI 110049 9811093380 11 A000112 NARINDERJIT SINGH ANAND WZ-111 A, IInd FLOOR,GALI NO. 5 SHIV NAGAR NEW DELHI 110058 9899829719 12 A000118 VIJAY KUMAR AGGARWAL 2, CHURCH ROAD DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 13 A000122 ARUN KUMAR C-49, SECTOR-41 GAUTAM BUDH NAGAR NOIDA 201301 9873097311 14 A000123 RAMESH CHAND AGGARWAL B-306, NEW FRIENDS COLONY NEW DELHI 110025 989178293 15 A000126 ARVIND KISHORE 86 GOLF LINKS NEW DELHI 110003 9810418755 16 A000127 BHARAT KUMR AHLUWALIA B-136 SWASTHYA VIHAR, VIKAS MARG DELHI 110092 9818830138 17 A000132 MONA AGGARWAL 2 - CHURCH ROAD, DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 18 A000133 SUSHIL KUMAR AJMANI F-76 KIRTI NAGAR NEW DELHI 110015 9810128527 19 A000140 PRADIP KUMAR AGGARWAL DISCO COMPOUND, G.T. -

776 785 Dt 05022015A.Pdf

Reminder - 1 GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION: WELFARE BRANCH PATRACHAR VIDYALYA, TIMARPUR: NEW DELHI CIRCULAR Sub s- List of School Teachers in rIo Financial Assistance (NFTWIfor the academic year 2011-12 received from MHRD, GOI. It is informed that Financial Assistance under the Scheme of 'Support for Professional Education of Children of School Teachers' for the academic year 2011-12 has been received from Ministry of Human Resource Development (Department of School Education & Literacy), Govt. of India. (List available on the website at www.edude1.nic.in on public circular). Some teachers still have not collect their cheque, It is once again requested to collect their cheque personally from Welfare Branch (Room No.7, Patrachar Building, 'Timarpur, Delhi), Directorate of Education, Govt. of NCT of Delhi, Timarpur, Delhi w.e.f. 09.02.2015 to 27.02.2015 between 11.30 a.m, to 3.30 p.m, (lunch hours 1.30 p.m. to 2.00 p.m.] on all working days. They should collect cheque before or after duty hours. They are requested to bring their Identity Card and specimen signature duly attested by HOS along with one rupee revenue stamp for collection of cheque. rvJ~'l-'\-: "'" ,,,", (KAMLESH BAINS) DDE (WELFARE) Encl. As above. Copy to :- No.F.DE.23 (432)/NFI'W /Wel./2011-12/7 76-7 es: Dated: os/0:2./1 ) 1. PS to Pr. Secretary Education, Directorate of Education, Old Sectt. 2. PS to Director Education, Directorate of Education, Old Sectt. 3. PS to Director Education,South M.C.D, Civic Centre, Minto Road, N.Delhi. -

Problems and Status of Muslim Graveyards in Delhi

PROBLEMS AND STATUS OF MUSLIM GRAVEYARDS IN DELHI A REPORT DELHI MINORITIES COMMISSION Government of NCT of Delhi C- Block, First Floor, Vikas Bhawan, I.P. Estate New Delhi 110002 Cover photo: A scene from Batla House graveyard Study conducted for Delhi Minorities Commission By HUMAN DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY 27-O, Pocket 2, MIG Complex, Mayur Vihar, Phase 3, Delhi- 110096 Telephone: 011-22621867, 09971222966 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.hdsindia.org FOREWORD Delhi Minorities Commission is pleased to publish this study on Muslim graveyards in the NCT of Delhi. This study was commissioned by the previous Commission headed by Shri Qamar Ahmad but could not be finalised and published during its tenure. The new Commission, which took over on 20 July, 2017, found this study among the pending work. We took it up with due diligence and urgency. After going through the draft, we called a meeting with Human Development Society’s director and researcher. Now it is being published with some changes and addition of some information and data. This study is an eye-opener. It tells us that a majority of Muslim graveyards registered with Delhi Waqf Board (DWB) and other agencies has practically disappeared over the years. Both public and government agencies have occupied or encroached upon graveyards, while new land is not being earmarked for new qabristans in town-planning schemes. The study has found that the remaining space in the existing qarbristans is hardly enough for two more years. DMC will approach Govt. of NCT of Delhi and its agencies, especially Delhi Waqf Board and Delhi Development Authority, to quickly solve this grave problem before it is too late. -

Efficacy of Public Toilets in Delhi Cantonment: a Study of Their Maintenance

EFFICACY OF PUBLIC TOILETS IN DELHI CANTONMENT: A STUDY OF THEIR MAINTENANCE A Dissertation submitted to Panjab University, Chandigarh for award of Master of Philosophy in Social Sciences, in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Advanced Professional Programme in Public Administration (APPPA) By Air Commodore Siruvuri Sridhar VM RollNo : 4540 Under the Guidance of Dr. Saket Bihari 45thAdvanced Professional Programme In Public Administration (APPPA) INDIANINSTITUTE OFPUBLICADMINISTRATION NEWDELHI 2019-20 CERTIFICATE I have the pleasure to certify that the dissertation titled“Efficacy of Public Toilets in Delhi Cantonment: A Study of their Maintenance” is a bonafide research work carried out by Air Commodore Siruvuri Sridhar VM under my guidance and supervision. The dissertation is a result of his own research and to the best of my knowledge no part of it has earlier comprised in other monograph, dissertation or book. This is being submitted to the Panjab University, Chandigarh, for the award of Master of Philosophy in Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Advanced Professional Programme in Public Administration (APPPA) of the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA), New Delhi. I recommend that the dissertation of Air Commodore Siruvuri Sridhar VM is worthy of consideration for the award of M. Phil degree of the Panjab University, Chandigarh. (Dr Saket Bihari) Associate Professor Indian Institute of Public Administration I.P Estate, NewDelhi - 1100012 Place: New Delhi Date: i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Saket Bihari, Associate Professor in Development Studies, Indian Institute of Public Administration, for his guidance in writing of this dissertation. -

Sdissfinal 4

Abstract CHATTERJEE, SUDESHNA. Children’s Friendship with Place: An Exploration of Environmental Child Friendliness of Children’s Environments in Cities. (Under the direction of Prof. Robin C. Moore.) The Child Friendly Cities is a concept for making cities friendly for all children especially in UN member countries that have ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (i.e., all except the United States) through municipal action. This idea is particularly important for improving the quality of life of poor urban children who are most affected by sweeping changes brought about by globalization and rapid urbanization in the developing nations of the global South. However, there is no theoretical understanding of a construct such as environmental child friendliness that could guide planning and design of child friendly environments in cities. Resulting from an integrative review of a large body of interdisciplinary literature, a new six- dimensional construct based on children’s friendship needs, called children’s place friendship, is proposed as underpinning environmental child friendliness from an environment-behavior perspective. The study disaggregates the idea of the child friendly city into numerous interlocking child friendly places that children themselves consider friendly based on their own experiences. These child friendly places support the six dimensions of place friendship in different ways: care and respect for places, meaningful exchange with places, learning and competence through place experience, creating and controlling territories, having secret places, and freedom of expression in places. An in-depth analytic ethnography was conducted in a low-income, high-density, mixed-use neighborhood in New Delhi, India, with children in their middle-childhood to validate and elaborate this conceptual framework. -

Delhi Cantonment Board

DELHI CANTONMENT BOARD Proceedings of Ordinary Cantonment Board Meeting held on 13.10.2020 at 1100 hours in the Conference Room of the Cantonment Board Office, Delhi Cantonment. MEMBERS PRESENT 1. Brig. R.K. Chaudhary President 2. Smt. Kadiyan Rachna Vice-President 3. Sh. S.V.R. Chandra Sekhar, CEO Member–Secretary 4. Brig. S.S. Jaiswal, SEMO Ex-officio Member 5. Lt. Col. Sandeep Singh Nominated Member 6. Col. Parshant Kandpal, CO (DAPU) Nominated Member 7. Col. Brajesh Kumar, SO(Cantt) Nominated Member 8. Maj. Amit Bhardwaj, GE (Central) Ex-officio Member 9. Smt. Jain Kavita Elected Member 10. Sh. Jagat Singh Elected Member 11. Sh. Beniwal Nand Kishore Elected Member 12. Col. Narender Chaudhary (Retd) Elected Member 13. Sh. Vimal Chowdhary Elected Member 14. Smt. Chaudhary Priyanka Elected Member MEMBERS ABSENT 1. Sh. D. Karthikeyan, ADM Nominated Member 2. Sh. Tanwar Sandeep Elected Member SPECIAL INVITEE PRESENT 1. Sh. Virender Singh Kadian, Hon’ble MLA SPECIAL INVITEE ABSENT 1. Smt. Meenakashi Lekhi, Hon’ble MP National Anthem was played before proceeding with the meeting. Before start of the proceedings, Board Members stood in silence for two minutes to pay condolences to Brig. B.K. Rattanpal, Ex- President, Cantt Board Delhi who had expired recently due to illness. 1. OATH Oath of the Member-Secretary, Delhi Cantonment Board under section 17 of the Cantonments Act, 2006. Page 1 of 210 1. Sh. S.V.R. Chandra Sekhar, CEO, Delhi Cantonment Board took oath of the allegiance to the Constitution of India as provided in Section 17 of the Cantonments Act, 2006. -

Conservation & Heritage Management

Chapter – 7 : Conservation & Heritage Management IL&FS ECOSMART Chapter – 7 Conservation & Heritage Management CHAPTER - 7 CONSERVATION & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT 7.1 INTRODUCTION Heritage Resource Conservation and Management imperatives for Delhi The distinctive historical pattern of development of Delhi, with sixteen identified capital cities1 located in different parts of the triangular area between the Aravalli ridge and the Yamuna river, has resulted in the distribution of a large number of highly significant heritage resources, mainly dating from the 13th century onwards, as an integral component within the contemporary city environment. (Map-1) In addition, as many of these heritage resources (Ashokan rock edict, two World Heritage Sites, most ASI protected monuments) are closely associated with the ridge, existing water systems, forests and open space networks, they exemplify the traditional link between natural and cultural resources which needs to be enhanced and strengthened in order to improve Delhi’s environment. (Map -2) 7.1.1 Heritage Typologies – Location and Significance These heritage resources continue to be of great significance and relevance to any sustainable development planning vision for Delhi, encompassing a vast range of heritage typologies2, including: 1. Archaeological sites, 2. Fortifications, citadels, different types of palace buildings and administrative complexes, 3. Religious structures and complexes, including Dargah complexes 4. Memorials, funerary structures, tombs 5. Historic gardens, 6. Traditional networks associated with systems of water harvesting and management 1 Indraprastha ( c. 1st millennium BCE), Dilli, Surajpal’s Surajkund, Anangpal’s Lal Kot, Prithviraj Chauhan’s Qila Rai Pithora, Kaiquabad’s Khilokhri, Alauddin Khilji’s Siri, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq’s Tughlaqabad, Muhammad Bin Tughlaq’s Jahanpanah, Firoz Shah Tughlaq’s Firozabad, Khizr Khan’s Khizrabad, Mubarak Shah’s Mubarakabad, Humayun’s Dinpanah, Sher Shah Suri’s Dilli Sher Shahi, Shah Jehan’s Shahjehanabad, and Lutyen’s New Delhi.