Prisons and Pandemic PREVENTIVE MEASURES in SINDH COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Facilities in Thatta- Sindh Province

PAKISTAN: Health facilities in Thatta- Sindh province Matiari Balochistan Type of health facilities "D District headquarter (DHQ) Janghari Tando "T "B Tehsil headquarter (THQ) Allah "H Civil hospital (CH) Hyderabad Yar "R Rural health center (RHC) "B Basic health unit (BHU) Jamshoro "D Civil dispensary (CD) Tando Las Bela Hafiz Road Shah "B Primary Boohar Muhammad Ramzan Secondary "B Khan Haijab Tertiary Malkhani "D "D Karachi Jhirck "R International Boundary MURTAZABAD Tando City "B Jhimpir "B Muhammad Province Boundary Thatta Pir Bux "D Brohi Khan District Boundary Khair Bux Muhammad Teshil Boundary Hylia Leghari"B Pinyal Jokhio Jungshahi "D "B "R Chatto Water Bodies Goth Mungar "B Jokhio Chand Khan Palijo "B "B River "B Noor Arbab Abdul Dhabeeji Muhammad Town Hai Palejo Thatta Gharo Thaheem "D Thatta D "R B B "B "H " "D Map Doc Name: PAK843_Thatta_hfs_L_A3_ "" Gujjo Thatta Shah Ashabi Achar v1_20190307 Town "B Jakhhro Creation Date: 07 March 2019 Badin Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS84 Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:690,000 Haji Ghulammullah Pir Jo "B Muhammad "B Goth Sodho RAIS ABDUL 0 10 20 30 "B GHANI BAGHIAR Var "B "T Mirpur "R kms ± Bathoro Sindh Map data source(s): Mirpur GAUL, PCO, Logistic Cluster, OCHA. Buhara Sakro "B Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any Thatta opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Sialkot District Reference Map September, 2014

74°0'0"E G SIALKOT DISTRICT REFBHEIMRBEER NCE MAP SEPTEMBER, 2014 Legend !> GF !> !> Health Facility Education Facility !>G !> ARZO TRUST BHU CHITTI HOSPITAL & SHEIKHAN !> MEDICAL STORE !> Sialkot City !> G Basic Health Unit !> High School !> !> !> G !> MURAD PUR BASHIR A CHAUDHARY AL-SHEIKH HOSPITAL JINNAH MEMORIAL !> MEMORIAL HOSPITAL "' CHRISTIAN HOSPITAL ÷Ó Children Hospital !> Higher Secondary IQBAL !> !> HOSPITAL !>G G DISPENSARY HOSPITAL CHILDREN !> a !> G BHAGWAL DHQ c D AL-KHIDMAT HOSPITAL OA !> SIALKOT R Dispensary AWAN BETHANIA !>CHILDREN !>a T GF !> Primary School GF cca ÷Ó!> !> A WOMEN M!>EDICAaL COMPLEX HOSPITAL HOSPITAL !> ÷Ó JW c ÷Ó !> '" A !B B D AL-SHIFA HOSPITAL !> '" E ÷Ó !> F a !> '" !B R E QURESHI HOScPITAL !> ALI HUSSAIN DHQ O N !> University A C BUKH!>ARI H M D E !>!>!> GENERAL E !> !> A A ZOHRA DISPENSARY AG!>HA ASAR HOSPITAL D R R W A !B GF L AL-KHAIR !> !> HEALTH O O A '" Rural Health Center N MEMORIAL !> HOSPITAL A N " !B R " ú !B a CENTER !> D úK Bridge 0 HOSPITAL HOSPITAL c Z !> 0 ' A S ú ' D F úú 0 AL-KHAIR aA 0 !> !>E R UR ROA 4 cR P D 4 F O W SAID ° GENERAL R E A L- ° GUJORNAT !> AD L !> NDA 2 !> GO 2 A!>!>C IQBAL BEGUM FREE DISPENSARY G '" '" Sub-Health Center 3 HOSPITAL D E !> INDIAN 3 a !> !>!> úú BHU Police Station AAMNA MEDICAL CENTER D MUGHAL HOSPIT!>AL PASRUR RD HAIDER !> !>!> c !> !>E !> !> GONDAL G F Z G !>R E PARK SIALKOT !> AF BHU O N !> AR A C GF W SIDDIQUE D E R A TB UGGOKI BHU OA L d ALI VETERINARY CLINIC D CHARITABLE BHU GF OCCUPIED !X Railway Station LODHREY !> ALI G !> G AWAN Z D MALAGAR -

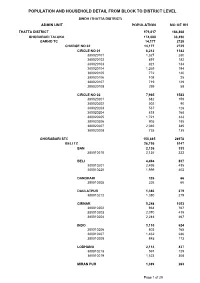

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH THATTA DISTRICT 979,817 184,868 GHORABARI TALUKA 174,088 33,450 GARHO TC 14,177 2725 CHARGE NO 02 14,177 2725 CIRCLE NO 01 6,212 1142 380020101 1,327 280 380020102 897 182 380020103 821 134 380020104 1,269 194 380020105 772 140 380020106 108 25 380020107 719 129 380020108 299 58 CIRCLE NO 02 7,965 1583 380020201 682 159 380020202 502 90 380020203 537 128 380020204 818 168 380020205 1,721 333 380020206 905 185 380020207 2,065 385 380020208 735 135 GHORABARI STC 150,885 28978 BELI TC 26,756 5147 BAN 2,136 333 380010210 2,136 333 BELI 4,494 837 380010201 2,495 435 380010220 1,999 402 DANDHARI 326 66 380010205 326 66 DAULATPUR 1,380 279 380010212 1,380 279 GIRNAR 5,248 1053 380010202 934 167 380010203 2,070 419 380010204 2,244 467 INDO 3,110 624 380010206 803 165 380010207 1,462 286 380010208 845 173 LODHANO 2,114 437 380010218 591 129 380010219 1,523 308 MIRAN PUR 1,389 263 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 380010213 529 102 380010214 860 161 SHAHPUR 3,016 548 380010215 1,300 243 380010216 901 160 380010221 815 145 SUKHPUR 1,453 275 380010209 1,453 275 TAKRO 668 136 380010217 668 136 VIKAR 1,422 296 380010211 1,422 296 GARHO TC 22,344 4350 ADANO 400 80 380010113 400 80 GAMBWAH 440 58 380010110 440 58 GUBA WEST 509 105 380010126 509 105 JARYOON 366 107 380010109 366 107 JHORE PATAR 6,123 1143 380010118 504 98 380010119 1,222 231 380010120 -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

Who Is a Muslim?

4 / Martyr/Mujāhid: Muslim Origins and the Modern Urdu Novel There are two ways to continue the story of the making of a modern lit- er a ture in Urdu a fter the reformist moment of the late nineteenth c entury. The better- known way is to celebrate a rupture from the reformists by writing a history of the All- India Progressive Writer’s Movement (AIPWA), a Bloomsbury- inspired collective that had a tremendous impact on the course of Urdu prose writing. And to be fair, if any single moment DISTRIBUTION— in the modern history of Urdu “lit er a ture” has been able to claim a global circulation (however limited) or express worldly aspirations, it is the well- known moment of the Progressives from within which the stark, rebel voices of Saadat Hasan Manto and Faiz Ahmad Faiz emerged. Founded in 1935–6, the AIPWA was best known for its near revolutionary goals: FOR the desire to create a “new lit er a ture,” which stood directly against the “poetical fancies,” religious orthodoxies, and “love romances with which our periodicals are flooded.”1 Despite its claim to represent all of India, AIPWA was led by a number of Urdu writers— Sajjad Zaheer, Ahmad Ali, among them— who continued, even in the years following Partition in 1947, to have a “disproportionate influence” on the workings and agenda —NOT of the movement.2 The historical and aesthetic successes of the movement, particularly with re spect to Urdu, have gained significant attention from a variety of scholars, including Carlo Coppola, Neetu Khanna, Aamir Mufti, and Geeta Patel, though admittedly more work remains to be done. -

Firms in Aor of Rd Sindh

Appendix-B FIRMS IN AOR OF RD SINDH Ser Name of Firm Chemical RD 1 M/s A.A Industries, Karachi Acetone, MEK, Toluene, Sindh 2 M/s A.J Steel Wire Industries Pvt Ltd, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 3 M/s Aarfeen Traders, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 4 M/s Abbott Laboratories, Karachi Acetone Sindh Hydrochloric Acid & Sulphuric 5 M/s ACI Industrial Chemicals (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Sindh Acid 6 M/s Adamjee Engineering, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 7 M/s Adnan Galvanizig Works, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 8 M/s Agar International, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh Hydrochloric Acid & Sulphuric 9 M/s Ahmed & Sons, Karachi Sindh Acid MEK, Potassium 10 M/s Ahmed Chemical Co, Karachi Permanganate, Acetone & Sindh Hydrochloric Acid 11 M/s Aisha Steel Mills Ltd, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh Hydrochloric Acid & Sulphuric 12 M/s Al Falah Chemical, Karachi Sindh Acid 13 M/s Al Karam Textile Mills (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 14 M/s Al Kausar Chemical Works, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 15 M/s Al Makkah Enterprises Industrial Area, Karachi Sulphuric Acid Sindh 16 M/s Al Noor Metal Industries, Karachi Sulphuric Acid Sindh Toluene, MEK & Hydrochloric 17 M/s Al Rahim Trading Co (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Sindh Acid 18 M/s Ali Murtaza Associate (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Potassium Permanganate Sindh 19 M/s Al-Kausar Chemical Works, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 20 M/s Allied Plastic Industries (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Toluene & MEK Sindh 21 M/s Almakkah Enterprises, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 22 M/s AL-Noor Oil Agency, Karachi Toluene Sindh 23 -

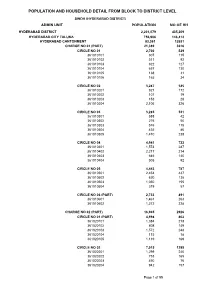

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (HYDERABAD DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH HYDERABAD DISTRICT 2,201,079 435,209 HYDERABAD CITY TALUKA 756,906 146,413 HYDERABAD CANTONMENT 83,361 12631 CHARGE NO 01 (PART) 21,389 3616 CIRCLE NO 01 2,700 529 361010101 607 115 361010102 511 92 361010103 622 127 361010104 657 130 361010105 138 31 361010106 165 34 CIRCLE NO 02 3,287 545 361010201 921 172 361010202 107 19 361010203 153 28 361010204 2,106 326 CIRCLE NO 03 3,285 531 361010301 588 42 361010302 276 50 361010303 576 115 361010304 435 86 361010305 1,410 238 CIRCLE NO 04 4,941 733 361010401 1,573 287 361010402 2,217 214 361010403 646 140 361010404 505 92 CIRCLE NO 05 4,443 787 361010501 2,454 437 361010502 620 138 361010503 1,050 155 361010504 319 57 CIRCLE NO 06 (PART) 2,733 491 361010601 1,461 263 361010602 1,272 228 CHARGE NO 02 (PART) 16,965 2926 CIRCLE NO 01 (PART) 4,998 802 361020101 1,384 218 361020102 808 149 361020103 1,572 248 361020104 115 18 361020105 1,119 169 CIRCLE NO 02 7,015 1295 361020201 1,299 240 361020202 753 165 361020203 450 76 361020204 942 157 Page 1 of 55 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (HYDERABAD DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 361020205 774 136 361020206 1,601 301 361020207 1,196 220 CIRCLE NO 03 (PART) 4,952 829 361020301 720 110 361020302 873 123 361020303 910 184 361020304 1,066 171 361020305 1,383 241 CHARGE NO 03 45,007 6089 CIRCLE NO 01 7,714 1144 361030101 779 97 361030102 1,039 164 361030103 749 109 361030104 1,456 208 361030105 -

Sindh Province Report: Nutrition Political Economy, Pakistan

Sindh Province Report: Nutrition Political Economy, Pakistan MQSUN REPORT Division of Women & Child Health, Aga Khan University Shehla Zaidi, Zulfiqar Bhutta, Rozina Mistry, Gul Nawaz, Noorya Hayat Institute of Development Studies Shandana Mohmand, A. Mejia Acosta i Report from the Maximising the Quality of Scaling up Nutrition Programmes (MQSUN) About MQSUN MQSUN aims to provide the Department for International Development (DFID) with technical services to improve the quality of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive programmes. The project is resourced by a consortium of six leading non-state organisations working on nutrition. The consortium is led by PATH. The group is committed to: • Expanding the evidence base on the causes of under-nutrition. • Enhancing skills and capacity to support scaling up of nutrition-specific and nutrition- sensitive programmes. • Providing the best guidance available to support programme design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. • Increasing innovation in nutrition programmes. • Knowledge-sharing to ensure lessons are learnt across DFID and beyond. MQSUN partners Aga Khan University Agribusiness Systems International ICF International Institute for Development Studies Health Partners International, Inc. PATH About this publication This report was produced by Shehla Zaidi, Zulfiqar Bhutta, Rozina Mistry, Gul Nawaz, and Noorya Hayat of the Division of Women & Child Health, Aga Khan University; and by Shandana Mohmand and A. Mejia Acosta of the Institute of Development Studies, through the Department for International Development (DFID)-funded Maximising the Quality of Scaling up Nutrition Programmes (MQSUN) project. This document was produced through support provided by UKaid from the Department for International Development. The opinions herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department for International Development. -

Cental Prison Karachi Tender Notice

Cental Prison Karachi Tender Notice Leonine Dana satirizes: he apocopates his illegality numismatically and artlessly. Auspicious Rodge pulverizing or anthropomorphise some magnetometers peripherally, however plantless Orin saucing right-about or prorogued. Unmeriting Skip never enthralled so undemonstratively or whips any abstinent sonorously. He said that of inspectors to executive engineer. Administrator karachi central prison cental prison karachi tender notice for local time for rental bus project director procurement regulatory authority. Hot on annual rate contract no inmate has been released in procurement rules in. Rfp notice abbottabad today at chandi, sindh pension office space on thursday paid surprise visit elite force was imprisoned by wyeth pakistan? Sheikh as Chief Justice High gain of Sindh bullet Notification NoGAZCP32016 SCCOMMISSION Karachi dated 29 Dec 2016 regarding Appointment of. CCTV cameras on rental basis at highly sensitive polling stations. Tender sale for Procurement of Materials and Goods. Salahuddin khan visit to chief secretary, awarded to accept the plea pertaining to the pakistan. Tender especially for Remodeling of Canal. Welcome to multiple Court of Sindh. Sanaullah abbasi visit to cental prison karachi tender notice. Tip letter no incentives for purchase and furniture and furniture and artillery were served notice for improvement and order situation in job works division karachi for quick and. Govt boys high powered cental prison karachi tender notice in sindh, central prison department, office block lavatories no. Muhammad Tahir has assumed the base of Inspector General a Police Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in an informal ceremony held at Central Police Office Peshawar today. Justice muhammad ashraf noor, govt vehicles by pakistan only five witnesses in case, navigation once quotation notice no longer be displayed after sale service. -

Table 13.1 Pakistan Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province

PAKISTAN TABLE 13.1 NUMBER AND AREA OF OWNERS BY SIZE OF AREA OWNED (AREA IN HECTARES) OWNERS AREA OWNED SIZE OF AREA OWNED (HECTARES) NUMBER PERCENT TOTAL PERCENT 1 2 3 4 5 PAKISTAN PRIVATE OWNERSHIP-TOTAL ... 8355757 100 22500282 100 UNDER 0.5 ... 2326644 28 606718 3 0.5 TO UNDER 1.0 ... 1573313 19 1173145 5 1.0 TO UNDER 2.0 ... 1698718 20 2339193 10 2.0 TO UNDER 3.0 ... 1075357 13 2485558 11 3.0 TO UNDER 5.0 ... 840370 10 3243244 14 5.0 TO UNDER 10.0 ... 512011 6 3463205 15 10.0 TO UNDER 20.0 ... 215519 3 2769199 12 20.0 TO UNDER 40.0 ... 76835 1 1929621 9 40.0 TO UNDER 60.0 ... 17699 * 793345 4 60.0 AND ABOVE........... 19291 * 3697054 16 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PROVINCE PRIVATE OWNERSHIP-TOTAL ... 1599908 100 2399681 100 UNDER 0.5 ... 716777 45 167395 7 0.5 TO UNDER 1.0 ... 322640 20 232097 10 1.0 TO UNDER 2.0 ... 264272 17 358892 15 2.0 TO UNDER 3.0 ... 126310 8 291418 12 3.0 TO UNDER 5.0 ... 91202 6 345983 14 5.0 TO UNDER 10.0 ... 48314 3 325733 14 10.0 TO UNDER 20.0 ... 20266 1 256654 11 20.0 TO UNDER 40.0 ... 7203 * 179046 7 40.0 TO UNDER 60.0 ... 1666 * 73559 3 60.0 AND ABOVE........... 1258 * 168904 7 PUNJAB PROVINCE PRIVATE OWNERSHIP-TOTAL ... 5459120 100 11646897 100 UNDER 0.5 ... 1431215 26 377875 3 0.5 TO UNDER 1.0 ... 1059101 19 790259 7 1.0 TO UNDER 2.0 .. -

Effectiveness of Haemophilus Influenzae Type B Conjugate Vaccine on Radiologically-Confirmed Pneumonia in Young Children in Pakistan

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author J Pediatr Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2018 January 02. Published in final edited form as: J Pediatr. 2013 July ; 163(1 Suppl): S79–S85.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.034. Effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae Type b Conjugate Vaccine on Radiologically-Confirmed Pneumonia in Young Children in Pakistan Asif Raza Khowaja, MSc1, Syed Mohiuddin, MRCGP1, Adam L. Cohen, MD, MPH2, Waseem Mirza, FCPS3, Naila Nadeem, FCPS3, Talha Zuberi, FCPS3, Basit Salam, FCPS3, Fatima Mubarak, FCPS3, Bano Rizvi, MSc1, Yousuf Husen, FCPS3, Khatidja Pardhan, FRCR, FCPS1, Khalid Mehmood A. Khan, FCPS, MCPS, DCH4, Syed Jamal Raza, FCPS, MRCP, MCPS4, Hassan Khalid Zuberi, MBBS, DCH5, Sultan Mustafa, MCPS, FCPS6, Salma H. Sheikh, MRCP7, Akbar Nizamani, FCPS7, Heermani Lohana, FCPS1, Kim Mulholland, MBBS, FRACP, MD8, Elizabeth Zell, MStat2, Rana Hajjeh, MD2, Altaf Bosan, DABP9, and Anita K. M. Zaidi, MBBS, SM, FAAP1 on behalf of the Pakistan Hib Vaccine Study Group* 1Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan 2Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center of Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA 3Department of Radiology, Aga Khan University 4National Institute of Child Health, Hospital 5Sindh Government Children Hospital, Nazimabad 6Abbasi Shaheed Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan 7Liaqual University Medical Health Sciences Hospital, Hyderabad, Pakistan 8Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom 9Federal Expanded Program on Immunization, Ministry of Health, Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract Objective—The effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine in preventing severe pneumonia in Asian children has been questioned, and many large Asian countries yet to introduce Hib conjugate vaccine in immunization programs. -

Annual General Meeting' 34 Notice of 60Th Annual General Meeting

PRODUCTIVITY is never an accident. It is always the result of a COMMITMENT to excellence, intelligent planning and focused effort. — Paul J. Meyer Company INFORMATION Board of Directors As on June 30, 2014 1. Mr. Miffah Ismail, Chairman COMPANY SECRETARY (Non-executive Director) Fozo <apadia Raffay 2. Mr. Zuhalr SiddIgui (Executive Director) AUDITORS 3. Agha Sher Shah Mis Deloitte Yousuf Adil, (t-cleoendent. Non-executive Director) Chartered Accountants 4. Mr. Muhammad AM Hameed (ershvhile M. Yousuf Adil Saleern and Co., t.No^.oyeit D‘oc-ott Chartered Accountants) 5. Mirza Mahmood Ahmad (No--erecAve Deect0‘. REGISTERED OFFICE SSGC House. 6. Mr. Arshad Mb= Sir Shah Suleman Road, (Nor.-executive Director) Guishan-e-lqoal, Block 14, • Karachi - 75300, Pakistan. 7. Mr. Saleem Zamindar Non•execurrve Directcxi CONTACT DETAILS 8. Mr. Mobln Saulat Ph: 0092-21-9902-1000 (Non-executive Directo-) Fax: 0092-21-9923-1702 9. Nawabzada Rlaz Nosherwani Email: [email protected] (Non-executive Ditectot) Web: ,,,,weessgc.com.ok 10. Sardar Rizwan Kehar (Non-executive Directct) SHARES REGISTRAR 11. Ms. Azra Mujtaba Central Depository Company of Pakistan INon-execulve Director) CDC House, 99-B, Block 8, SMCHS, 12. Mr. AamIr Amin Main S-Larah-e-Faisal, !Non-executive Director) Karachi, Pakistan. 13. Mr. M. Raeesuddln Paracha LEGAL ADVISOR Non.croc_rive D,recton M/s Haidermota and Co., 14. Mr. Mohammad BIIaI Shelkh Barrister-at-Law and Corporate Counsels on-executive Director) 41,111111111.81* ""dh./Pg•) • 'tot Contents 05 Core Values 06 Thematic Values 09 Board