Pierrot's Silence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surviving Set Theory: a Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory

Surviving Set Theory: A Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Angela N. Ripley, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: David Clampitt, Advisor Anna Gawboy Johanna Devaney Copyright by Angela N. Ripley 2015 Abstract Undergraduate music students often experience a high learning curve when they first encounter pitch-class set theory, an analytical system very different from those they have studied previously. Students sometimes find the abstractions of integer notation and the mathematical orientation of set theory foreign or even frightening (Kleppinger 2010), and the dissonance of the atonal repertoire studied often engenders their resistance (Root 2010). Pedagogical games can help mitigate student resistance and trepidation. Table games like Bingo (Gillespie 2000) and Poker (Gingerich 1991) have been adapted to suit college-level classes in music theory. Familiar television shows provide another source of pedagogical games; for example, Berry (2008; 2015) adapts the show Survivor to frame a unit on theory fundamentals. However, none of these pedagogical games engage pitch- class set theory during a multi-week unit of study. In my dissertation, I adapt the show Survivor to frame a four-week unit on pitch- class set theory (introducing topics ranging from pitch-class sets to twelve-tone rows) during a sophomore-level theory course. As on the show, students of different achievement levels work together in small groups, or “tribes,” to complete worksheets called “challenges”; however, in an important modification to the structure of the show, no students are voted out of their tribes. -

Resistance Through 'Robber Talk'

Emily Zobel Marshall Leeds Beckett University [email protected] Resistance through ‘Robber Talk’: Storytelling Strategies and the Carnival Trickster The Midnight Robber is a quintessential Trinidadian carnival ‘badman.’ Dressed in a black sombrero adorned with skulls and coffin-shaped shoes, his long, eloquent speeches descend from the West African ‘griot’ (storyteller) tradition and detail the vengeance he will wreak on his oppressors. He exemplifies many of the practices that are central to Caribbean carnival culture - resistance to officialdom, linguistic innovation and the disruptive nature of play, parody and humour. Elements of the Midnight Robber’s dress and speech are directly descended from West African dress and oral traditions (Warner-Lewis, 1991, p.83). Like other tricksters of West African origin in the Americas, Anansi and Brer Rabbit, the Midnight Robber relies on his verbal agility to thwart officialdom and triumph over his adversaries. He is, as Rodger Abrahams identified, a Caribbean ‘Man of Words’, and deeply imbedded in Caribbean speech-making traditions (Abrahams, 1983). This article will examine the cultural trajectory of the Midnight Robber and then go on to explore his journey from oral to literary form in the twenty-first century, demonstrating how Jamaican author Nalo Hopkinson and Trinidadian Keith Jardim have drawn from his revolutionary energy to challenge authoritarian power through linguistic and literary skill. The parallels between the Midnight Robber and trickster figures Anansi and Brer Rabbit are numerous. Anansi is symbolic of the malleability and ambiguity of language and the roots of the tales can be traced back to the Asante of Ghana (Marshall, 2012). -

Circulation and Permanence of French Naturalist Literature in Brazil

Circulation and Permanence of French Naturalist Literature in Brazil Pedro Paulo GARCIA FERREIRA CATHARINA Federal University of Rio de Janeiro RÉSUMÉ Cet article se propose de retracer la présence de la littérature naturaliste française au Brésil à partir de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle jusqu’en 1914, en mettant en relief son importance et sa diversité dans le champ littéraire brésilien ainsi que sa permanence à travers l’association avec d’autres formes d’art, notamment le théâtre et le cinéma. À l’appui, il présente des données qui témoignent de la circulation dans le pays des œuvres des principaux écrivains naturalistes français le long de cette période et de l’existence d’un public varié de lecteurs. Enfin, il montre comment ces écrivains naturalistes devenus des célébrités ont pu exercer leur emprise au- delà de la sphère littéraire proprement dite, surtout sur la mode et les coutumes The reader, who on 10 January 1884 thumbed through a copy of the newspaper Gazeta de notícias from Rio de Janeiro, could find on page two an announcement about a curious fashion item – the literary bracelet. The object that was “to cause an uproar among wealthy women” comprised twelve gold coins inserted into two chains containing, on the back, the name of the owner’s favourite authors. The decorative item was a “kind of confession” of the wearer’s literary preferences: […] For example, the ladies who favour naturalist literature will carry the names of Zola, Goncourt, Maupassant, Eça de Queirós, Aluísio Azevedo, etc. The ladies who are more inclined to the romantic school will adopt on their bracelets the names of Rousseau, Byron, Musset, Garret, Macedo, etc. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY An Jingfu (1994) The Pain of a Half Taoist: Taoist Principles, Chinese Landscape Painting, and King of the Children . In Linda C. Ehrlich and David Desser (eds.). Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan . Austin: University of Texas Press, 117–25. Anderson, Marston (1990) The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period . Berkeley: University of California Press. Anon (1937) “Yueyu pian zhengming yundong” [“Jyutpin zingming wandung” or Cantonese fi lm rectifi cation movement]. Lingxing [ Ling Sing ] 7, no. 15 (June 27, 1937): no page. Appelo, Tim (2014) ‘Wong Kar Wai Says His 108-Minute “The Grandmaster” Is Not “A Watered-Down Version”’, The Hollywood Reporter (6 January), http:// www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wong-kar-wai-says-his-668633 . Aristotle (1996) Poetics , trans. Malcolm Heath (London: Penguin Books). Arroyo, José (2000) Introduction by José Arroyo (ed.) Action/Spectacle: A Sight and Sound Reader (London: BFI Publishing), vii-xv. Astruc, Alexandre (2009) ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo ’ in Peter Graham with Ginette Vincendeau (eds.) The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks (London: BFI and Palgrave Macmillan), 31–7. Bao, Weihong (2015) Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915–1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). Barthes, Roland (1968a) Elements of Semiology (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1968b) Writing Degree Zero (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1972) Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), New York: Hill and Wang. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 203 G. -

Pierrot Lunaire Translation

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) Pierrot Lunaire, Op.21 (1912) Poems in French by Albert Giraud (1860–1929) German text by Otto Erich Hartleben (1864-1905) English translation of the French by Brian Cohen Mondestrunken Ivresse de Lune Moondrunk Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder, A flots verts de la Lune coule, Flows nightly from the Moon in torrents, Und eine Springflut überschwemmt Et submerge comme une houle And as the tide overflows Den stillen Horizont. Les horizons silencieux. The quiet distant land. Gelüste schauerlich und süß, De doux conseils pernicieux In sweet and terrible words Durchschwimmen ohne Zahl die Fluten! Dans le philtre yagent en foule: This potent liquor floods: Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder. A flots verts de la Lune coule. Flows from the moon in raw torrents. Der Dichter, den die Andacht treibt, Le Poète religieux The poet, ecstatic, Berauscht sich an dem heilgen Tranke, De l'étrange absinthe se soûle, Reeling from this strange drink, Gen Himmel wendet er verzückt Aspirant, - jusqu'à ce qu'il roule, Lifts up his entranced, Das Haupt und taumelnd saugt und schlürit er Le geste fou, la tête aux cieux,— Head to the sky, and drains,— Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt. Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux! The wine we drink with our eyes! Columbine A Colombine Colombine Des Mondlichts bleiche Bluten, Les fleurs -

Mapping Prostitution: Sex, Space, Taxonomy in the Fin- De-Siècle French Novel

Mapping Prostitution: Sex, Space, Taxonomy in the Fin- de-Siècle French Novel The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Tanner, Jessica Leigh. 2013. Mapping Prostitution: Sex, Space, Taxonomy in the Fin-de-Siècle French Novel. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10947429 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, WARNING: This file should NOT have been available for downloading from Harvard University’s DASH repository. Mapping Prostitution: Sex, Space, Taxonomy in the Fin-de-siècle French Novel A dissertation presented by Jessica Leigh Tanner to The Department of Romance Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Romance Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2013 © 2013 – Jessica Leigh Tanner All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Janet Beizer Jessica Leigh Tanner Mapping Prostitution: Sex, Space, Taxonomy in the Fin-de-siècle French Novel Abstract This dissertation examines representations of prostitution in male-authored French novels from the later nineteenth century. It proposes that prostitution has a map, and that realist and naturalist authors appropriate this cartography in the Second Empire and early Third Republic to make sense of a shifting and overhauled Paris perceived to resist mimetic literary inscription. Though always significant in realist and naturalist narrative, space is uniquely complicit in the novel of prostitution due to the contemporary policy of reglementarism, whose primary instrument was the mise en carte: an official registration that subjected prostitutes to moral and hygienic surveillance, but also “put them on the map,” classifying them according to their space of practice (such as the brothel or the boulevard). -

Rhetorical Strategies in Edmond De Goncourt's Japonisme

Pamela J. Warner Compare and Contrast: Rhetorical Strategies in Edmond de Goncourt's Japonisme Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 1 (Spring 2009) Citation: Pamela J. Warner, “Compare and Contrast: Rhetorical Strategies in Edmond de Goncourt's Japonisme,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 1 (Spring 2009), http:// www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring09/61-compare-and-contrast-rhetorical-strategies-in- edmond-de-goncourts-japonisme. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2009 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Warner: Compare and Contrast: Rhetorical Strategies in Edmond de Goncourt‘s Japonisme Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 1 (Spring 2009) Compare and Contrast: Rhetorical Strategies in Edmond de Goncourt's Japonisme by Pamela J. Warner After the opening of economic and cultural trade between Japan and Europe and the United States in 1854, a predominant view of Japanese art and culture as fundamentally different from their European equivalents began to dominate nineteenth-century European commentaries. For example, in an 1867 article, Zacharie Astruc spoke of "this Orient, so different from us." Japan's difference was exactly what made it so exciting to Astruc, who was enthusiastic about the "new inspiration" that could be drawn from "this far away people."[1] In 1868, Jules Champfleury agreed on the essential difference of Japanese art, but he condemned the growing fascination with its "bizarre use of color," as he described the impact of James McNeil Whistler's enthusiasm for Japanese lacquer-ware and kimonos. -

A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Alfred University Clowning

A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Alfred University Clowning as an Act of Social Critique, Subversive and Cathartic Laughter, and Compassion in the Modern Age by Danny Gray In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Alfred University Honors Program May 9th, 2016 Under the Supervision of: Chair: Stephen Crosby Committee Members: M. Nazim Kourgli David Terry “Behind clowns, sources of empathy, masters of the absurd, of humor, they who draw me into an inexplicable space-time capsule, who make my tears flow for no reason. Behind clowns, I am surprised to sense over and over again humble people, insignificant we might even say, stubbornly incapable of explaining, outside the ring, the unique magic of their art.” - Leandre Ribera “The genius of clowning is transforming the little, everyday annoyances, not only overcoming, but actually transforming them into something strange and terrific. It is the power to extract mirth for millions out of nothing and less than nothing.” - Grock 1 Contents Introduction 3 I: Defining Clown 5 II: Clowning as a Social Institution 13 III: The Development of Clown in Western Culture 21 IV: Clowns in the New Millennium 30 Conclusion 39 References 41 2 The black and white fuzz billowed across the screen as my grandmother popped in a VHS tape: Saltimbanco, a long-running Cirque du Soleil show recorded in the mid-90’s. I think she wanted to distract me for an hour while she worked on a pot of gumbo, rather than stimulate an interest in circus life. Regardless, I was well and truly engrossed in the program. -

Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg's Pierrot

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Clown: Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire Mike Fabio Introduction In September of 1912, a 37-year-old Arnold Schoenberg sat in a Berlin concert hall awaiting the premier of his 21st opus, Pierrot Lunaire. A frail man, as rash in his temperament as he was docile when listening to his music, Schoenberg watched as the lights dimmed and a fully costumed Pierrot took to the stage, a spotlight illuminating him against a semitransparent black screen through which a small instrumental ensemble could be seen. But as Pierrot began singing, the audience quickly grew uneasy, noting that Pierrot was in fact a woman singing in the most awkward of styles against a backdrop of pointillist atonal brilliance. Certainly this was not Beethoven. In a review of the concert, music critic James Huneker wrote: The very ecstasy of the hideous!…Schoenberg is…the cruelest of all composers, for he mingles with his music sharp daggers at white heat, with which he pares away tiny slices of his victim’s flesh. Anon he twists the knife in the fresh wound and you receive another thrill…. There is no melodic or harmonic line, only a series of points, dots, dashes or phrases that sob and scream, despair, explode, exalt and blaspheme.1 Schoenberg was no stranger to criticism of this nature. He had grown increasingly contemptuous of critics, many of whom dismissed his music outright, even in his early years. When Schoenberg entered his atonal period after 1908, the criticism became far more outrageous, and audiences were noted to have rioted and left the theater in the middle of pieces. -

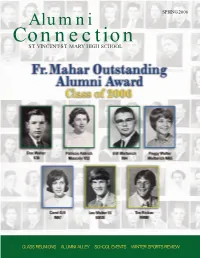

Alumni Connection Winter

Alumni SPRING 2006 Connection ST. VINCENT-ST. MARY HIGH SCHOOL CLASS REUNIONS ALUMNI ALLEY SCHOOL EVENTS WINTER SPORTS REVIEW IT’S HAPPENING HERE 5 IN THIS ISSUE MEMORIAL MASS: The Miller Family 3 WALL OF VISION The Wall of Vision is a tribute to the lead donors in the Share the Vision capital campaign. 18 MAHAR OUTSTANDING ALUMNI AWARD 2006 This award honors living graduates of St. Vincent, St. Mary and St. Vincent- St. Mary high schools. There are six recipients this year. 22 THROUGH THESE DOORS... Read about the wonderful work our faculty and staff is doing. 6 1FIRST WORD ALUMNI ALLEY: Jane McCormish Sparhawk V39 is a photogra- pher. Pictured above is an example of her work. Read more about Jane and other alumni in Alumni Alley. Russian Mural 8 IN CELEBRATION OF THEIR ADMIRATION OF THE RUSSIAN CULTURE and as a CLASS REUNIONS: V70 classmates (L-R) Sue Gerbasi lasting momento for years to come, student volunteers from Russian Bartlebaugh, Betty Delagrange Schnitzler, Mary Ellen Phillips Club painted a colorful mural. This mural is on a wall in the room shared MacDonald and Mike Metzler by Mr. Neary, Drama and Mr. O’Neil, Russian Language. The design is an impressionistic representation of St. Basil’s Cathedral. The idea, for- mulated by senior Mamie Williamson, came from a design on a T-shirt bought in Russia. The design was copied onto a transparency using a scanner and then projected onto the wall where it was outlined in chalk and painted. Also helping with the mural were two graduates and for- mer Russian students, Brett Wenneman and Betsy Mason. -

This Work Has Been Submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Conference or Workshop Item Title: The fears of a clown Creator: Mackley, J. S. Example citation: Mackley, J. S. (2016) The fears of a clown. PapeRr presented to: The Dark Fantastic: Sixth Annual Joint Fantasy Symposium, The University of Northampton, 02 December 2016. A Version: Presented version T http://nectar.Cnorthampton.ac.uk/9062/ NE The Fears of the Clown J.S. Mackley – University of Northampton “The clown may be the source of mirth, but - who shall make the clown laugh?” Angela Carter, Nights at the Circus Many of us read Stephen King’s IT before we were re-terrorised by Tim Curry’s portrayal of Pennywise the Clown and his psychotic mania in the 1990 mini-series. It is said that “Stephen King’s movie IT … did for clowns what Psycho did for showers and what Jaws did for swimming in the ocean.”1 But, many of us had already had our psyches attuned to the danger of clowns when we saw the scene in Steven Spielberg’s 1982 film Poltergeist when we looked at the maniacal grinning face of the Robbie’s clown sitting on the chair during a thunderstorm. The viewers all knew that clown would come to life – changing from the friendly-faced doll, to the demonic entity that drags Robbie under the bed … For many of us, these two depictions of clowns may be the root of Coulrophobia – a “persistent, abnormal, and irrational fear of clowns”. Clowns hover on the peripheries of our fears. -

Lolita Fashion, Like Other Japanese Subcultures, Developed As a Response a to Social Pressures and Anxieties Felt by Young Women and Men in the 1970S and 1980S

Lolita: Dreaming, Despairing, Defying Lolita: D, D, D J New York University a p As it exists in Japan, Lolita Fashion, like other Japanese subcultures, developed as a response a to social pressures and anxieties felt by young women and men in the 1970s and 1980s. Rather than dealing with the difficult reality of rapid commercialization, destabilization of society, n a rigid social system, and an increasingly body-focused fashion norm, a select group of youth chose to find comfort in the over-the-top imaginary world of lace, frills, bows, tulle, and ribbons that is Lolita Fashion. However, the more gothic elements of the style reflect that behind this cute façade lurks the dark, sinister knowledge that this ploy will inevitably end, the real world unchanged. Background: What is Lolita Fashion? in black boots tied with pink ribbon. Her brown If one enters the basement of street fashion hair has been curled into soft waves and a small hub Laforet in Harajuku, Tokyo, one will come pink rose adorns her left ear. across a curious fashion creature found almost exclusively in Japan: an adult woman, usually Although the women (and occasionally men) in in her late teens or early twenties, dressed like Laforet look slightly different, they all share the a doll. Indeed, the frst store one enters, Angelic same basic elements in their appearance: long, Pretty, looks very much like a little girl’s dream curled hair, frilly dresses, delicate head-dresses doll house. The walls and furniture are pink or elaborate bonnets, knee-socks, round-toed and decorated with tea-sets, cookies, and teddy Mary Janes, round-collared blouses and pouffy, bears.