Norfolk Coast AONB Climate Change Adaptation Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Significance of the Landscape

Norfolk Coast AONB Management Plan 2014-19 Supporting Information The significance of the Norfolk Coast landscape Summarised from 'The Norfolk Coast Landscape: An assessment of the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty' (Countryside Commission, CCP 486, 1995). This document is now out of print and not available in digital format, but a copy is available at the Norfolk Coast Partnership office if you wish to read it in full. AONB designation Judging the importance of a particular area of landscape is no easy matter. The importance and value attached to the Norfolk Coast landscape has already been reflected by its designation, in 1968, as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) as well as by the separate definition in 1975 of a more limited part of the area as a Heritage Coast. It is helpful to consider the area's special qualities under four main headings: ● the value of the landscape as part of the national and regional landscape resource , by virtue of its rarity or representativeness, and including comparison with other areas of similar landscape character and with the surrounding landscape; ● the scenic qualities of the landscape, including the particular combination of landscape elements, aesthetic qualities, local distinctiveness and 'sense of place'; ● evidence about how the landscape is perceived and valued by the general public and by writers and others who may have been inspired by it; ● other special values attached to the landscape including historical and cultural associations and special conservation interests, relating to features of outstanding nature conservation or archaeological interest. Summarised below are the ways in which the Norfolk Coast demonstrates these qualities to an extent that makes the area a truly outstanding landscape. -

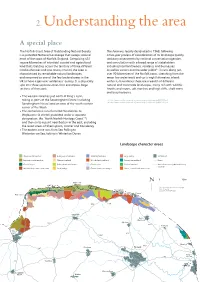

Understanding the Area

2. Understanding the area A special place The Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty The Area was legally designated in 1968, following is a protected National Landscape that sweeps around a five-year process of consideration of its landscape quality, most of the coast of Norfolk, England. Comprising 451 statutory assessments by national conservation agencies, square kilometres of intertidal, coastal and agricultural and consultation with a broad range of stakeholders, land that stretches across the territory of three different including local landowners, residents and businesses, local authorities and one county council, the Area is as well as visitors and the wider public14. It runs along just characterised by remarkable natural landscapes, over 90 kilometres of the Norfolk coast, stretching from the and renowned as one of the few lowland areas in the mean low water mark and up to eight kilometres inland; UK to have a genuine ‘wilderness’ quality. It is physically within its boundaries there are a wealth of different split into three separate zones that encompass large natural and manmade landscapes, many rich with wildlife: sections of the coast: heaths and moors, salt marshes and high cliffs, chalk rivers and busy harbours. • The western zone lies just north of King’s Lynn, taking in parts of the Sandringham Estate (including 13. http://www.norfolkcoastaonb.org.uk/mediaps/pdfuploads/pd003377.pdf Sandringham House) and an area of the south-eastern 14. http://www.norfolkcoastaonb.org.uk/mediaps/pdfuploads/pd001161.pdf corner -

Sheringham – Pf/21/0405

SHERINGHAM – PF/21/0405 - Use of land for siting of shipping container to store water sports equipment for a limited period from beginning of April until end of September (2021 and 2022), with removal of container outside those dates Land on The Promenade, Sheringham, Norfolk Minor Development Target Date: 20.04.2021 Extension of Time: 14.05.2021 Case Officer: Russell Stock Full Planning Permission RELEVANT SITE CONSTRAINTS Adjacent to the Undeveloped Coast England Coast Path Coastal Margin Within an ‘Open Land Area’ Within an area of ‘Public Realm’ Within the Settlement Boundary of Sheringham Sheringham Shore County Geodiversity Site Setting of North Norfolk Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Setting of Sheringham Conservation Area RELEVANT PLANNING HISTORY None. THE APPLICATION Site description: The application site consists of a section of the West Sheringham Promenade which juts out in front of an area of covered and uncovered seating and public toilets. The Marble Arch, which is found in this location is one of the key access/egress routes from the town onto the promenade and beach. The Lees gardens, play areas and the car parking along The Esplanade are located further to the south. Access to the beach in this location is provided via metal steps on either side of the section of promenade which juts out seaward. The promenade is of concrete construction with metal safety railings on the seaward edge. Proposal: This application seeks permission for the use of the land for the siting of a shipping container to store water sports equipment during the summer season (April – September). -

Natural Capital Evidence Compendium for Norfolk and Suffolk October 2020

Introduction Regional Context Asset Inventory Risk Review Implications References Natural Capital Evidence Compendium for Norfolk and Suffolk October 2020 Asset Inventory Land Soil & Sub-Surface Habitats & Species Freshwater Coast & Marine Atmosphere : 30oct20_FINAL Photos: Trudie Dockerty UEA unless otherwise stated. Introduction Regional Context Asset Inventory Risk Review Implications References About this compendium The counties of Norfolk and Suffolk have stewardship of a wealth of natural assets. The purpose of this Evidence Compendium is to present information about these assets and the potential risks to them, to provide an element of the preparatory work that will feed into a Norfolk & Suffolk 25 Year Environment Plan. Where possible, data is provided by county and also for five important natural areas within them: the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and Suffolk Coasts & Heaths AONB, plus The Broads National Park, The Brecks and the Dedham Vale AONB. (These are termed ‘key natural areas’ throughout this compendium). The Introduction section outlines the scope of the work and the approach taken. This is followed with background information regarding the environmental and socio-economic setting of the two counties to provide some Regional Context. A key part of the work is a Natural Asset Inventory for Norfolk and Suffolk which is presented in six sections - Land Soil & Sub-Surface Habitats & Species Freshwater Coast & Marine Atmosphere This is followed by an examination of the current and future risks to these assets, presented in a Risk Review, with a synthesis of the Implications and outline of Priorities and next steps for the proposed Norfolk & Suffolk 25 Year Environment Plan. -

A Gis Based Spatial Decision Support System for Landscape Character Assessment

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2012 A GIS BASED SPATIAL DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM FOR LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT Davey, Faye Elanor http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1168 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. A GIS BASED SPATIAL DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM FOR LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT By FAYE ELANOR DAVEY A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Marine Science and Engineering Faculty of Science In collaboration with the Tamar Valley AONB Partnership August 2012 Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. i Abstract A GIS BASED SPATIAL DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM FOR LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT Faye Elanor Davey Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) provides a structured approach to identifying the character and distinctiveness about the landscape. It is a tool used to identify what makes a location unique, a set of techniques and procedures used to map differences between landscapes based on their physical, cultural and historical characteristics. -

SURREY HILLS AGLV REVIEW By

SURREY HILLS AGLV REVIEW by Chris Burnett Associates 26 06 07 for SPOA Final report Chris Burnett Associates 2007 Chris Burnett Associates, Landscape Architects, White House Farm , Shocklach, Malpas, Cheshire SY14 7BN Tel : 01829 250646 Fax 01829 250527 [email protected] www.chris-burnett-associates.co.uk Surrey AGLV Review : Final report Chris Burnett Associates 26 06 07 CONTENTS: Executive Summary Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: Historic Development of the Surrey AGLV Chapter 3: Current Planning Policies and Consultation Chapter 4: A review of the national context for Local landscape Designations Chapter 5: Approach and Methodology Chapter 6: Findings Chapter 7: Recommendations 2 Surrey AGLV Review : Final report Chris Burnett Associates 26 06 07 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7KHLVVXHRIWKHVWDWXVRI/RFDO/DQGVFDSH'HVLJQDWLRQV //'·V KDVEHHQKLJKOLJKWHGE\WKHUHFHQW advice issued by the government and embodied in PPS 7. This states that a landscape character assessment linked to criteria based policy approach should provide sufficient protection for these areas provided such designations are based on a formal and robust assessment of the qualities of the landscape concerned. Against this background, Chris Burnett Associates (CBA) were commissioned to undertake a review of the Surrey AGLV by the Surrey Planning Officers Association. (SPOA) The study commenced with a review of historic background. It established that the Surrey Hills AONB is closely linked with the designation of the AGLV. The first County Plan approved in 1958 showed the first AGLV area, which was a smaller area incorporating the North Downs escarpment and the area of Greensand Hills surrounding Leith Hill. The AONB designated in the same year incorporated the original AGLV area but was much larger including the Greensand Valleys, the whole of the Frensham / Devils Punch Bowl plateau and parts of the Wooded Weald. -

Morston, Blakeney and Cley Classic North Norfolk

Directions... The bus ride From the Bittern Line rail station When you arrive in Morston At the National Trail finger post At Blakeney, walk along the Take a trip to see the seals at Follow the sea bank and the After crossing the River The bus ride Leaving Blakeney the bus climbs This walk of approximately 4 miles, taking at Sheringham walk across the alight from the Coasthopper turn right along the top of the quay to opposite the toilets. Blakeney Point, watch bait acorn out and round to Cley. Glaven descend the steps The Coasthopper bus provides up and over the Blakeney esker. road and into Station Approach and walk past The Anchor sea defence bank. You are now Here you will see another diggers on the mud flats or terns If you find steps difficult you into Cley village. a great platform to get a good A great view point from where around two hours to complete, takes you to the to the Coasthopper stop outside pub and take the next right on the Norfolk Coast Path National Trail finger post on the windswept shingle. will need to leave the path at view of the Norfolk coastline. you fleetingly get good views edge of the land and the sea. A special place. Explore the village of Cley, a the tourist information centre. signed Morston Quay. Keep National Trail, which runs from pointing out along the sea Cley where it reaches the main across Morston to Wells. Find out more about Blakeney mecca for birdwatchers with a Look out for views of the coast, Catch the bus to Morston. -

SURREY HILLS AGLV REVIEW By

SURREY HILLS AGLV REVIEW by Chris Burnett Associates 26 06 07 for SPOA Final report Chris Burnett Associates 2007 Chris Burnett Associates, Landscape Architects, White House Farm , Shocklach, Malpas, Cheshire SY14 7BN Tel : 01829 250646 Fax 01829 250527 [email protected] www.chris-burnett-associates.co.uk Surrey AGLV Review : Final report Chris Burnett Associates 26 06 07 CONTENTS: Executive Summary Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: Historic Development of the Surrey AGLV Chapter 3: Current Planning Policies and Consultation Chapter 4: A review of the national context for Local landscape Designations Chapter 5: Approach and Methodology Chapter 6: Findings Chapter 7: Recommendations 2 Surrey AGLV Review : Final report Chris Burnett Associates 26 06 07 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The issue of the status of Local Landscape Designations (LLD’s) has been highlighted by the recent advice issued by the government and embodied in PPS 7. This states that a landscape character assessment linked to criteria based policy approach should provide sufficient protection for these areas provided such designations are based on a formal and robust assessment of the qualities of the landscape concerned. Against this background, Chris Burnett Associates (CBA) were commissioned to undertake a review of the Surrey AGLV by the Surrey Planning Officers Association. (SPOA) The study commenced with a review of historic background. It established that the Surrey Hills AONB is closely linked with the designation of the AGLV. The first County Plan approved in 1958 showed the first AGLV area, which was a smaller area incorporating the North Downs escarpment and the area of Greensand Hills surrounding Leith Hill. -

NAAONB Annual General Meeting Business Meeting Agenda Thursday 19Th November 2020 10.30-11.30 A.M

NAAONB Annual General Meeting Business Meeting Agenda Thursday 19th November 2020 10.30-11.30 a.m. Meeting to be held by videoconference 01584 892112 (Clare Elbourne) Item 1 Apologies Item 2 Introduction of current NAAONB Board members (verbal) for information Item 3 AGM November 28th, 2019 - Minutes and matters arising for agreement Item 4 Art in the Landscape National Strategy (Kate Wood, Activate) for information Item 5 Chairman’s Annual Report 2019-20 for information. Item 6 Financial Report 2019-20 for agreement Item 7 CEO’s Report of work completed for NAAONB Business Plan Oct 2019 - Oct 2020 for information. Item 8 Review of Memorandum and Articles of Association for agreement Item 9 Membership Rates for Individual Lifetime Membership for agreement Item 10 Election of Trustees and appointment of auditors for agreement Item 11 AOB The National Association for Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Belmont House, Shrewsbury Business Park Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6LG 01584 892112 [email protected] Twitter @NAAONB A company limited by guarantee no: 4729800 1 Charity Number: 1158871 Registered office as above Item 3 - AGM November 28th 2019 - Minutes and matters arising Report to The Annual General Meeting of the National Association for AONBs Subject AGM November 28th 2019 - Minutes and matters arising Date 19th November 2020 Purpose For agreement MINUTES OF THE NAAONB ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 2019 Thursday 28th November 2019 3.15 - 5.00pm Broadway House, Tothill Street, London, SW1H 9NQ Attendees Blackdown Hills -

Blakeney Freshes, Norfolk Coast AONB

Protected landscapes walk… 3 miles t THE NATIONAL TRUST Blakeney Freshes, Norfolk Coast AONB It’s not hard to see why this area is part of an AONB… it’s fantastic for The area of freshwater marsh spotting wildlife, especially birds, and the views as you stroll around and reedbed, known as Blakeney Point and harbour are excellent. Discover its beauty on this walk Blakeney Freshes, falls within through the enchanting village of Blakeney and around Blakeney Freshes. the Norfolk Coast AONB, which was founded in 1968, Start and Blakeney National Nature Bus stop, Blakeney Church (TG032436). Maps: Landranger 133/Explorer 251 Reserve. It’s a great spot to Getting here experience Norfolk’s open, By foot: Norfolk Coast Path runs 45 miles from Hunstanton to Cromer, remote and wild landscape. passing Blakeney By bike: Norfolk Coast Cycleway (National Cycle Route 30) runs along quiet © NTPL / Joe Cornish lanes from King’s Lynn to Cromer, it is an easy 1 mile detour to Blakeney The Norfolk Coast AONB is By bus: Norfolk Coasthopper, Sheringham-Hunstanton. Go to well known for its birdlife. In www.norfolkgreen.co.uk for details of bus times winter, look out for large By road: A149 Sheringham to King’s Lynn coast road swirling flocks of Golden plover move between the Local facilities harbour and the marshes, WCs at Blakeney & Morston Quay (not NT), refreshments, pubs & car parks while ducks and geese, like at Blakeney, Morston & Stiffkey. Dogs welcome on Coasthopper bus and Wigeon, and the black and ferries to Blakeney Point white Brent Geese (pictured) graze in the fields. -

STIFFKEY – PF/20/1202: Conversion of Former Army Training Buildings

STIFFKEY – PF/20/1202: Conversion of former army training buildings into four holiday lets suitable for disabled persons: Former Army Buildings, Greenway, Stiffkey for L G Harrison & Son Target Date: 10 December 2020 Case Officer: Jayne Owen Full application CONSTRAINTS LDF Tourism Asset Zone SFRA - Areas Susceptible to Groundwater Flooding Public Right of Way EA Risk of Flooding from Surface Water 1 in 1000 Landscape Character Area Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty LDF - Countryside Undeveloped Coast A Road Development within 60m of Class A road RELEVANT PLANNING HISTORY PF/19/2122 Former Army Buildings, Greenway, Stiffkey Conversion and alterations of former army training building to four holiday lets - Refused 4 March 2020 on the following grounds: 1. The site lies within an area designated as Undeveloped Coast where it is considered that the proposed development does not require a coastal location and would be detrimental to the distinctive open coastal character of the designated Undeveloped Coast, contrary to Policy EN 3 of the adopted Core Strategy and Paragraph 170 of the NPPF. 2. The development site is isolated from the main settlement of Stiffkey and from the campsite and surrounding buildings on Greenway. The development and access would be visible on the rise of land from the coast path and the domestication of the site through the conversion of the buildings to holiday accommodation and thereby introducing domestic features into the landscape such as cars, people and light will have an adverse impact on the special qualities of the AONB, namely that of tranquillity, sense of remoteness and wildness and the strong and distinctive links between land and sea and will have significant impacts with respect to light pollution. -

Transactions 1926

TRANSACTIONS OF THE B info lit anti Borlniclj NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY Presented to Members for 1926-27 VOL. XII.— Part hi NORWICH Printed by A. E. Soman & Co. December, 1927 Prick 10 - ) Burfolk ant> BinjUmij Baf«rali»t»’ Snctefg Patron H.M. the king Vice-Patron H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES, K.G. ™ OFFICERS FOR 1927—28 President H. J. HOWARD, F.L.S. Ex-President E. H. HANKIN, M.A.. Sc.D. Vice-Presidents HER GRACE THE DUCHESS OF BEDFORD, F.Z.S., F.L.S., Hon.M.B.O.U. THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL OF LEICESTER, G.C.V.O., C.M.G. THE RIGHT HON. VISCOUNT GREY OF FALLODON, P.C., K.G. MICHAEL BEVERLEY, M.D. SIR SIDNEY F. HARMER, K.B.E., F.R.S. SIR EUSTACE GURNEY, M.A., F.Z.S. PROF. F. W. OLIVER, D.Sc., F.R.S. Hon. Treasurer ROBERT GURNEY, D.Sc. Ingham Old Hall Norwich Hon. Secretary SYDNEY H. LONG, M.D., F.Z.S. 31, Surrey Street, Norwich Hon. Secretary, Junior Branch MISS B. WATERFIELD Attlebridge Hon. Librarian F. C. HINDE Hon. Editor ROBERT GURNEY Hon. Auditor W. A. NICHOLSON Committee H. BACK H. J. HOWARD D. PAYLER D. CARRUTHERS H. H. HALLS H. J. THOULESS L. MISS WATERFIELD R. J. COLMAN CAPT. LLOYD Wild Birds' Protection Committee Chairman R. J. COLMAN ( S. H. LONG (Hon. Secretary) Q. E. GURNEY H. H. HALLS R. GURNEY B. B. RIVIERE LORD WILLIAM PERCY — TRANSACTIONS OK THE NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY The1. Committee beg to direct the attention of authors of communications to the Society to the following Regulations 2.