NOT TOO RICH, NOT TOO POOR Britain's Mrs. Miniver As The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the New York Stock Exchange Really Works David Kramer

How the New York Stock Exchange Really Works David Kramer Object 1 Object 2 Object 3 Richard Ney on the Role of the Specialist by Michael Templain “The story is told that after he had been deported to Italy, Lucky Luciano granted an interview in which he described a visit to the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. When the operations of floor specialists had been explained to him, he said, ‘A terrible thing happened. I realized I’d joined the wrong mob’” (1Ney, 8). It was with these words that Richard Ney began his first of three books on the nature of the New York Stock Exchange. Ney wrote over 20 years ago, a time when a 750 Dow was high and today’s volumes were beyond imagining. Some of his material is dated, and must be read in the light in which it was written. But the main premise of his books is still true: that the specialist exists not to ensure the free and orderly trade of stock in a particular company, but to fatten upon the innocence and ignorance of the small investor. The New York Stock Exchange is not an auction market (2Ney, 86), though many investors still hold onto that image. It is a rigged market. Volume is an effect of price. Prices are controlled absolutely by the specialists, the ‘market makers’ in individual stocks. It was this discovery that led Mr. Ney to eventually give us small investors a priceless gift: enlightenment. “Studying the transactions in each stock, I became immediately conscious that, on too many occasion to be a coincidence, a stock would advance from its morning low and then, often during the afternoon, would show an up-tick of a half-point or more on a large block of anywhere from 1,500 to 5,000 or more shares. -

Obituary All of Which Coiild Lead to Lavints

■ • ►V/ • -' 1. “ V.*', v - ' r." -■ V . ' /■• .■"V - ' t 1 .■ < . PAGE FOURTEEN FBIDAT, JULY «7» IM i: • Average Dopy Net Prcee R n The Weather ' For the Week EaiM xMattrlffHter^lEtrrttfctg 1|fralh ■at e< U. B. Wsathar El June 90, ISCI ■fa — ■ ■; a n d 'lfr A Russell K arker o T Oaiv- other propoh>d\ Unprovemeats ect. Ikiginetr Fusa^ ia M . wlX Frances Hbfron Coi&icll, Pythi Rec Bo^rd Adkg OUMDOl ir c » VA£Uk«MHr r, mOder tsaigh^ lA # A b o u t I W n an Sunshine Girls, will leave Mon 3 from Town ^ entry, is a graduate of ICanchbeter which UwilMd the tutaU ation o f be invited Aug. 13,601 day at B:Sbl a.in. fo r an oiiUng' at High S^ooL' two bUbUera to aerate the water, JULY M THRU AUO. U Wider Pool Apixm the regrading of a nearby slope MKIMliKBiS, M inlnr eC the AadH Ocean Beach, New London. Girls Bneaa ef Obeidattea'' Andernon SheH A uxiliary. V F ^ , are reminded to bring a' lunch'. ipid the conatriictkm of A drain NORTH HAVH»r (APT—Drum BERUBE’S) Tk FBWRITEB Bryant Grads m ers ^Ihd M en y tro m throughout UmdlmUir~^A CUy win hold a card party tonight at Those who need transportation may Idle,Cl 8 Dip The Advisory Park and Rec age ditch. The. entire bottom dt SERVICE : . y t at the port home. ' ■ call Mrs, Howard Smith, 300 N. the pool wlU be lined with aoil Connecticut v M gather here Aug. 479 E ast MOddls Tpksw Three h^chester area studenta reation Committee haf suggested cement. -

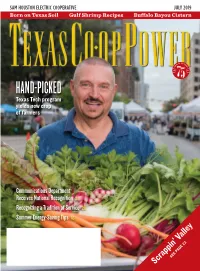

HAND-PICKED Texas Tech Program Yields New Crop of Farmers

1907_local covers custom.qxp 6/12/19 6:49 PM Page 8 SAM HOUSTON ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE JULY 2019 Born on Texas Soil Gulf Shrimp Recipes Buffalo Bayou Cistern HAND-PICKED Texas Tech program yields new crop of farmers Communications Department Receives National Recognition 21 Recognizing a Tradition of Service 20 Summer Energy-Saving Tips 18 SEE PAGE 22 Scrappin’ Valley Since 1944 July 2019 FAVORITES 5 Letters 6 Currents 18 Local Co-op News Get the latest information plus energy and safety tips from your cooperative. 29 Texas History Geronimo in San Antonio By Cyndy Irvine 31 Retro Recipes Gulf Shrimp 35 Focus on Texas Photo Contest: Trucks 36 Around Texas List of Local Events 38 Hit the Road What Lies Beneath By Chet Garner A class in a Texas Tech vineyard weighs ONLINE pruned clippings. TexasCoopPower.com Find these stories online if they don’t FEATURES appear in your edition of the magazine. Observations Native Soil How a simple bag of Texas dirt connects The First Hamburger 8 distant newborns to a beloved land. By Clay Coppedge By John Schwartz Texas USA Hands On Grown Locally Texas Tech program puts students By Joey Held 10 on a path to farm-to-table careers. Story by Sheryl Smith-Rodgers | Photos by Wyatt McSpadden NEXT MONTH SPECIAL Reliable as Electricity This ANNIVERSARY magazine, a trusted voice for ISSUE Texas co-ops, turns 75. 31 38 29 35 STUDENTS: WYATT MCSPADDEN. TCP ANNIVERSARY: DAVID VOGIN ON THE COVER Richard Ney, owner of Texas Food Ranch in Fredonia, at a farmers market in downtown Austin. -

Uhm Phd 9629825 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type ofcomputer printer. The quality ofthis reproduction is dependent upon the quality ofthe copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313n61-4700 800/521-0600 WALL STREET: SYMBOL OF AMERICAN CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 1996 By Michael Peter Gagne Dissertation Committee: Floyd Matson, Chair David Bertelson Paul Hooper Seymour Lutzky Richard Rapson UKI Number: 9629825 Copyright 1996 by Gagne, Michael Peter All rights reserved. -

Investing in Health Meet Mei-Lee Ney, the Trailblazer Behind the School’S Transformative $20 Million Gift

USC LEONARD DAVIS SCHOOL OF GERONTOLOGY VOL. 08 A Magazine for All Ages FALL FALL 2018 14 Investing in Health Meet Mei-Lee Ney, the trailblazer behind the school’s transformative $20 million gift FALL 2018 | 2 DEAN’S MESSAGE The USC Leonard Davis School of Geronotology is abuzz. Literally. Construction crews are hard at work bracing, bolting, drilling and ducting as we reconfigure spaces, including the first major update of our lobby since our building doors opened nearly half a century ago. Soon, students, faculty, staff and visitors will be welcomed to a renovated entryway, along with new second-floor office suites and basement labs, all evidence of the exciting changes in our school — changes precipitated by the growing size and importance of our field. We’re bursting with people, ideas, results. Energy. The redesign of our spaces reflects the importance of building a better future for all ages. In this issue, you will read about our work in home modification, including our collaboration with The Hartford Center for Mature Market Excellence, our annual Morton Kesten Universal Design Competition and the way we’ve updated our HomeMods.org website to help people age safely at home for as long as possible. You will also read about George Shannon, a suc- “We’re bursting cessful Hollywood actor who took on the new role of gerontology professor in his 60s. with people, On the research front, we’ve doubled our National Institutes of Health funding over the ideas, results. last six years. You will read about results from one of these projects: Professor Energy. -

Bert Lytell and Betty Compson in to Have and to Hold (C

Bert Lytell and Betty Compson in To Have and To Hold (c. 1923); see page 26. 22 ARLINGTON HISTORJCAL MAGAZINE A Century of Jamestown in the Cinema BY STEPHEN PATRICK For exactly one hundred years, filmed accounts and derivatives of the Jamestown story illustrated and romanticized this history onto the silver screen. And for this past century, Arlingtonians have enjoyed those narratives in a changing spectrum of cinematic venues. Arlington County citizens marked the fourth century of the founding of Jamestown in 2007 through celebrations, performances, exhibits, book clubs, tree plantings, and on and on. Repeatedly, an innocent question was asked about the relationship between far ago Stuart England's colonization of far away Jamestown with the northern Virginia county of Arlington. True, Captain John Smith, leader of the colony, explored the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries in 1608, and sailed up the Potomac to the spot that now is the Arlington shoreline, but seemingly any direct connections rest there. But Arlingtonians have a far deeper and more personal connection to early Jamestown, and that history is one hundred years old this year. 1 The Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition centered on the 1907 World's Fair; a sprawling celebration near Norfolk with exhibition buildings, states' showcase houses, reenactment tableaux for the audiences, and an exuberant presentation of the American past seen through the lens of the Progressive Era historians who portrayed the American story as a steady theme focused on the rights of man and the pursuit of happiness. Perhaps some people from Arlington were fortunate to travel by train or overnight steamship from Washington to Norfolk to see the Exhibition, but many more saw it in film. -

Carolina Coast MOREHEAD CITY, N.C

U.S. NAVAL BASE GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA Ginger Buffets Carolina Coast MOREHEAD CITY, N.C. (AP)--Hurricane Ginger slammed into the North Caro- lina coast this morning with winds reported up to 90 miles per hour. Ear- heading lier, Ginger was reported 30 miles southeast of Morehead City, northwest at about 15 mph. At that time thousands of people along the North Carolina coast had taken refuge inland where emergency disaster relief crews had been set up in strategic positions. Hurricane warnings were posted from northeast of Wilmington, N.C. to Vir- the ginia Beach, Va. And gale warnings were in effect elsewhere along North Carolina coast and northward from Virginia Beach to Rehobeth Beach, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 1971 Del., including the southern half of Chesapeake Bay. Winds and tides in the vicinity of Morehead City are ex- pected to cause heavy damage. Tides of up to seven feet are Thien's Foes Set Peopl e's Congress possible. Elsewhere in North Caro- and high winds SAIGON (AP)--Political foes of Sou th Vietnamese President Nguyen Van lina, heavy rains of the Thieu said they will hold a "people' s congress" tomorrow to unify opposi- are anticipated over most state. Rains of tion against Sunday's one-man presid ential election. eastern part of the inches will spread over The so-called Committee Against Dictatorship says the meeting will be up to four North Carolina and Virginia today held at Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky 's guest house. Some 2,000 delegates have been throughout the country are expected. and tonight. -

Title Catalog Link Section Call # Summary Starring 28 Days Later

Randall Library Horror Films -- October 2009 Check catalog link for availability Title Catalog link Section Call # Summary Starring 28 days later http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. DVD PN1995.9. An infirmary patient wakes up from a coma to Cillian Murphy, Naomie Harris, edu/record=b1917831 Horror H6 A124 an empty room ... in a vacant hospital ... in a Christopher Eccleston, Megan Burns, 2003 deserted city. A powerful virus, which locks Brendan Gleeson victims into a permanent state of murderous rage, has transformed the world around him into a seemingly desolate wasteland. Now a handful of survivors must fight to stay alive, 30 days of night http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. DVD PN1995.9. An isolated Alaskan town is plunged into Josh Hartnett, Melissa George, Danny edu/record=b2058882 Horror H6 A126 darkness for a month each year when the sun Huston, Ben Foster, Mark Boone, Jr., 2008 sinks below the horizon. As the last rays of Mark Rendall, Amber Sainsbury, Manu light fade, the town is attacked by a Bennett bloodthirsty gang of vampires bent on an uninterrupted orgy of destruction. Only the town's husband-and-wife Sheriff team stand 976-EVIL http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. VHS PN1995.9. A contemporary gothic tale of high-tech horror. Stephen Geoffreys, Sandy Dennis, edu/record=b1868584 Horror H6 N552 High school underdog Hoax Wilmoth fills up Lezlie Deane 1989 the idle hours in his seedy hometown fending off the local leather-jacketed thugs, avoiding his overbearing, religious fanatic mother and dreaming of a date with trailer park tempress Suzie. But his quietly desperate life takes a Alfred Hitchcock's http://uncclc.coast.uncwil. -

U. S. Ready To

J ' ^m iD AY, OCTOBER 1968 PAG«TWE!»Tt T/w^e Daily Net Press Ron For the Week Ended The Westlier Oot tZ, 1960 FoveeMt efC . ■. W m O m B m w # 13,250 Fwtly dandy, eeoler tMUgliib Member of-Ow Andlt Ixtw near '46. Snadny moeflir 4Ur, s Uttle orilden High i».6 «. JBurenn of Cnrenlntten. \ City o/ Village Charm • ' ' --I- r --1 ■ 1-1-11 —I n—^ 'Hi VOL. LXiX, 25 (TWELVE PAGES—TV SECTION) MANCHESTER,'C01W„ SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29. 1960 (ClauUled AdTerttalng on i ) PRICE FIVE CBNIB m m „ m^ m ill 4, all cash 3 in Union Raises GOP Hopes State News Convicted Ike Launclies Drive un i L ! .LAST 81/4 SALE HOURS AT O f Bribery For Nixon Triumph Lodge May Tour Indianapolis, Oct. 29 (A*)— State Once More Three top officials of the Car . Philadelphia, Oct. 29 (4>)— fhe wt9 act first and act fast. Hartford, Oct, 29 </P)— Re penters Union were convicted A free-swinging assault by America needs a man who will thinK first, and the act wisely.” i U. S. Ready to last night of bribing an Indi President Eisenhower on publican National Chairmap -Pennsylvania GOP leaders— once Thniston Morton flays Henty ana highway official in quicK- what he called Democratic confident of Keeping their state’s Cabot Lodge, the‘ Republican profit right-of-way deals, cli "irresponsibility” raised Re 32 importaiit electoral votes In the maxing a Jiighway scandal Republican column but recently vice presidential candidate, I ■., publican hopes . today ' for case that dated bacK nearly homestretch vigor in the final concqrned at signs of rising Ken may malte another campaigrn nedy strength. -

THIS WEEK in WALL STREET REFORM April 5 - 11, 2014

THIS WEEK IN WALL STREET REFORM April 5 - 11, 2014 We encourage you to forward this weekly compilation to friends and colleagues. To subscribe, email [email protected], with “This Week” in the sublet line. HIGH-FREQUENCY TRADING & DARK POOLS ‘Flash Boys’ Fuels More Calls for a Tax on Trading Nelson Schwartz, New York Times, 4/7/14 “It’s not every day that you find a fan club for new taxes, especially among economists and legal experts. But a burst of outrage in recent days generated by Michael Lewis’s new book about the adverse consequences of high-frequency trading on Wall Street has revived support in some quarters for a tax on financial transactions, with backers arguing that a tiny surcharge on trades would have many benefits. “’It kills three birds with one stone,’ said Lynn A. Stout, a professor at Cornell Law School, who has long followed issues of corporate governance and securities regulation. ‘From a public policy perspective, it’s a no-brainer.’” Will Flash Trades Now Lead to a Financial Transaction Tax? Peter Schroeder, The Hill, 4/6/14 “Renowned author Michael Lewis’s charge that the stock market is rigged against regular investors is making waves in Washington. Liberal lawmakers in particular believe Lewis is bringing critical attention to an issue that could boost their efforts to assign a tax on all financial transactions. “Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn.) joined with civil rights advocates Friday to hold a rally pushing his financial transaction tax bill. At the event, he mentioned Lewis’s book Flash Boys and blasted high-frequency traders as ‘predatory’ and ‘parasitic.’” The Michael Lewis Factor Zachary Warmbrodt and Dave Clarke, Politico, 4/5/14 Slow Cop, Fast Beat: SEC Takes Its Time on High-Frequency Trading Rules Dave Michaels, Matthew Philips & Silla Brush, Bloomberg, 4/10/14 “Yet White is in no rush. -

The Wall Street Specialist: King of the Jungle

Washington Law Review Volume 46 Number 4 7-1-1971 The Wall Street Specialist: King of the Jungle Donald Shelby Chisum University of Washington School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr Recommended Citation Donald S. Chisum, Reviews, The Wall Street Specialist: King of the Jungle, 46 Wash. L. Rev. 847 (1971). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol46/iss4/11 This Reviews is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Law Review by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEWS THE WALL STREET SPECIALIST: KING OF THE JUNGLE Donald Shelby Chisum* THE WALL STREET JUNGLE. By Richard Ney. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1970. Pp. 348. $7.50. The tone of The Wall Street Jungle is set in its preface: "[T] here is more sheer larceny per square foot on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange than any place else in the world."' The indicted principals are the specialists on the floor of the Exchange.2 Accessories include the whole Exchange establishment, insiders of the corporations whose stocks are listed on the Exchange, the Securities and Exchange Com- mission (SEC), the Federal Reserve Board, and members of Congress, all of whom are accused of acquiescing or even sharing in the special- ists' plunder. A close examination of Mr. Ney's bill of particulars reveals, however, that he exposes little about the persistent problem of the specialist and his function in the securities exchange auction mar- ket that has not already been debated in professional circles.3 In fact, as a piece of scholarship, the Jungle is a jungle itself, suffering from a lack of coherent organization. -

Amicus Curiae, December 16, 1965

George Washington University Law School Scholarly Commons Amicus Curiae, 1965 Amicus Curiae, 1960s 12-16-1965 Amicus Curiae, December 16, 1965 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/amicus_curiae_1965 Recommended Citation George Washington University Law School, 15 Amicus Curiae 3 (1965) This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Amicus Curiae, 1960s at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Amicus Curiae, 1965 by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. penl'oJ & Ogget vJ. a.u.: & Ctal't Van Vleck Finals 1\miru!i Tomorrow Night The final round of the Van Vleck Case Club arguments will be held tomorrow night, December 17, at 8 :00 p.m, in Tile Law .School, The case to be argued is William Shelton Winslow v. City of Van Vleck. The appellant-defendant will be represented by the team of Richard Blackburn and Robert Clark. Qtufiur The government will be represented by the team of James Penrod and Steve Ogge!. Both teams were un- defeated in the preliminary rounds. 'I'here will be a reception in Bacon Hall following the argument. All guests are invited to attend. The Case Club is honored to have as judges for this occasion three distinguished judges from the United pat{s![qnd States 'Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. by the <Student Bar and--------------------------George Washington in 1958. Association Judge Bastian was also an in- Law Review structor at the National Univer- sity Law Schoo!.