Biotech's Roots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RANDY SCHEKMAN Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, USA

GENES AND PROTEINS THAT CONTROL THE SECRETORY PATHWAY Nobel Lecture, 7 December 2013 by RANDY SCHEKMAN Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, USA. Introduction George Palade shared the 1974 Nobel Prize with Albert Claude and Christian de Duve for their pioneering work in the characterization of organelles interrelated by the process of secretion in mammalian cells and tissues. These three scholars established the modern field of cell biology and the tools of cell fractionation and thin section transmission electron microscopy. It was Palade’s genius in particular that revealed the organization of the secretory pathway. He discovered the ribosome and showed that it was poised on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where it engaged in the vectorial translocation of newly synthesized secretory polypeptides (1). And in a most elegant and technically challenging investigation, his group employed radioactive amino acids in a pulse-chase regimen to show by autoradiograpic exposure of thin sections on a photographic emulsion that secretory proteins progress in sequence from the ER through the Golgi apparatus into secretory granules, which then discharge their cargo by membrane fusion at the cell surface (1). He documented the role of vesicles as carriers of cargo between compartments and he formulated the hypothesis that membranes template their own production rather than form by a process of de novo biogenesis (1). As a university student I was ignorant of the important developments in cell biology; however, I learned of Palade’s work during my first year of graduate school in the Stanford biochemistry department. -

Moderna Appoints Oncology Leader Dr. Stephen Kelsey As President of Onkaido

Moderna Appoints Oncology Leader Dr. Stephen Kelsey as President of Onkaido Former Genentech executive to lead Moderna’s first venture company, focused exclusively in novel biology for oncology drug development CAMBRIDGE, Mass., July 1, 2014— Moderna Therapeutics, the pioneer in developing messenger RNA (mRNA) TherapeuticsTM, a revolutionary treatment modality to enable the in vivo production of therapeutic proteins, announced today that Stephen Kelsey, M.D., will become president of Onkaido Therapeutics, Moderna’s oncology drug development company, effective July 21. Launched in January of this year, Onkaido is Moderna’s first venture company, focused exclusively on developing and commercializing mRNA-based oncology treatments. “As we continue to grow Moderna and perfect our mRNA Therapeutics platform, we are also focused on building a transformational oncology company that will benefit patients and society. This requires hiring the best oncology talent to lead Onkaido,” said Stéphane Bancel, president and founding chief executive officer, Moderna. “Steve brings a wealth of experience in oncology drug development to his new role. His knowledge and leadership, combined with the team of Onkaido scientists and Moderna’s innovative mRNA technology, will help speed a new class of cancer drugs to patients around the world.” Dr. Kelsey has extensive pharmaceutical industry experience in oncology. After 16 years as an academic clinician, he started his industry career at Sugen, and later was vice president of hematology/oncology at Genentech. While at Genentech, Dr. Kelsey played a significant role in the development of key products Perjeta®, Kadcyla® and Erivedge®, as well as other molecules in the company’s oncology portfolio. He left Genentech in 2009 to run Geron’s oncology division, where he served for four years as executive vice president, research and development, and chief medical officer helping to develop therapeutics and vaccines to fight cancer. -

Print Layout 1

TECHNICAL PROGRAM Monday, March 19 5:00 – 8:00 pm Welcome Reception Tuesday, March 20 8:00 – 10:00 Session 1: Setting the Conference Context and Drivers Chair: Geoff Slaff (Amgen) Roger Perlmutter (Amgen) Conquering the Innovation Deficit in Drug Discovery Helen Winkle (CDER, FDA) Regulatory Modernization 10:00 – 10:30 Break Vendor and poster review 10:30 – 12:30 Session 2: Rapid Cell Line Development and Improved Expression System Development Chairs: Timothy Charlebois (Wyeth) and John Joly (Genentech) Amy Shen (Genentech) Stable Antibody Production Cell-Line Development with an Improved Selection Process and Accelerated Timeline Mark Leonard (Wyeth) High-Performing Cell-Line Development within a Rapid and Integrated Platform Process Control Pranhitha Reddy (Amgen) Applying Quality-by-Design to Cell Line Development Lin Zhang (Pfizer) Development of a Fully-Integrated Automated System for High-Throughput Screening and Selection of Single Cells Expressing Monoclonal Antibodies 12:30 – 2:00 Lunch Vendor and poster review 2:00 – 4:30 Session 3: High-Throughput Bulk Process Development Chairs: Brian Kelley (Wyeth) and Jorg Thommes (Biogen Idec) Colette Ranucci (Merck) Development of a Multi-Well Plate System for High-Throughput Process Development Min Zhang (SAFC Biosciences) CHO Media Library – an Efficient Platform for Rapid Development and Optimization of Cell Culture Media Supporting High Production of Pharmaceutical Proteins in Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells Nigel Titchener-Hooker The Use of Ultra-Scale-Down Approaches to Enable Rapid Investigation -

Genentech Tocilizumab Letter of Authority June 24 2021

June 24, 2021 Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd. C/O Genentech, Inc. Attention: Dhushy Thambipillai Regulatory Project Management 1 DNA Way, Bldg 45-1 South San Francisco, CA 94080 RE: Emergency Use Authorization 099 Dear Ms. Thambipillai: This letter is in response to Genentech, Inc.’s (Genentech) request that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issue an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the emergency use of Actemra1 (tocilizumab) for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in certain hospitalized patients, as described in the Scope of Authorization (Section II) of this letter, pursuant to Section 564 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the Act) (21 U.S.C. §360bbb-3). On February 4, 2020, pursuant to Section 564(b)(1)(C) of the Act, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) determined that there is a public health emergency that has a significant potential to affect national security or the health and security of United States citizens living abroad, and that involves the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).2 On the basis of such determination, the Secretary of HHS on March 27, 2020, declared that circumstances exist justifying the authorization of emergency use of drugs and biological products during the COVID-19 pandemic, pursuant to Section 564 of the Act (21 3 U.S.C. 360bbb-3), subject to terms of any authorization issued under that section. Actemra is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to both soluble and membrane-bound human IL-6 receptors (sIL-6R and mIL-6R) and subsequently inhibits IL- 6-mediated signaling through these receptors. -

A Short History of DNA Technology 1865 - Gregor Mendel the Father of Genetics

A Short History of DNA Technology 1865 - Gregor Mendel The Father of Genetics The Augustinian monastery in old Brno, Moravia 1865 - Gregor Mendel • Law of Segregation • Law of Independent Assortment • Law of Dominance 1865 1915 - T.H. Morgan Genetics of Drosophila • Short generation time • Easy to maintain • Only 4 pairs of chromosomes 1865 1915 - T.H. Morgan •Genes located on chromosomes •Sex-linked inheritance wild type mutant •Gene linkage 0 •Recombination long aristae short aristae •Genetic mapping gray black body 48.5 body (cross-over maps) 57.5 red eyes cinnabar eyes 67.0 normal wings vestigial wings 104.5 red eyes brown eyes 1865 1928 - Frederick Griffith “Rough” colonies “Smooth” colonies Transformation of Streptococcus pneumoniae Living Living Heat killed Heat killed S cells mixed S cells R cells S cells with living R cells capsule Living S cells in blood Bacterial sample from dead mouse Strain Injection Results 1865 Beadle & Tatum - 1941 One Gene - One Enzyme Hypothesis Neurospora crassa Ascus Ascospores placed X-rays Fruiting on complete body medium All grow Minimal + amino acids No growth Minimal Minimal + vitamins in mutants Fragments placed on minimal medium Minimal plus: Mutant deficient in enzyme that synthesizes arginine Cys Glu Arg Lys His 1865 Beadle & Tatum - 1941 Gene A Gene B Gene C Minimal Medium + Citruline + Arginine + Ornithine Wild type PrecursorEnz A OrnithineEnz B CitrulineEnz C Arginine Metabolic block Class I Precursor OrnithineEnz B CitrulineEnz C Arginine Mutants Class II Mutants PrecursorEnz A Ornithine -

Companies in Attendance

COMPANIES IN ATTENDANCE Abbott Diabetes Care Archbow Consulting LLC Business One Technologies Abbott Laboratories ARKRAY USA BusinessOneTech AbbVie Armory Hill Advocates, LLC CastiaRX ACADIA Artia Solutions Catalyst Acaria Health Asembia Celgene Accredo Assertio Therapeutics Celltrion Acer Therapeutics AssistRx Center for Creative Leadership Acorda Therapeutics Astellas Pharma US Inc. Cigna Actelion AstraZeneca Cigna Specialty Pharmacy AdhereTech Athenex Oncology Circassia Advantage Point Solutions Avanir Coeus Consulting Group Aerie Pharmaceuticals Avella Coherus Biosciences AGIOS AveXis Collaborative Associates LLC Aimmune Theraputics Bank of America Collegium Akcea Therapeutics Bausch Health Corsica Life Sciences Akebia Therapeutics Bayer U.S. CoverMyMeds Alder BioPharmaceuticals Becton Dickinson Creehan & Company, Inc., an Inovalon Company Alexion Biofrontera CSL Behring Alkermes Biogen Curant Health Allergan Biohaven CVS Health Almirall BioMarin D2 Consulting Alnylam BioMatrix Specialty Pharmacy Daiichi Sankyo Amarin BioPlus Specialty Pharmacy DBV Technologies Amber Pharmacy Bioventus Deloitte Consulting LLP AmerisourceBergen Blue Cross Blue Shield Association Dendreon Amgen Blue Fin Group Dermira Amicus Therapeutics bluebird bio Dexcom Amneal Boehringer Ingelheim Diplomat Pharmacy Anthem Boston Biomedical Dova Applied Policy Bowler and Company Decision Resources Group Aquestive Therapeutics Braeburn Eisai Arbor Pharmaceuticals Bristol-Myers Squibb 1 electroCore Indivior Merz Pharmaceuticals EMD Serono Inside Rx Milliman Encore Dermatology, -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE Media: Nikki Levy (650) 225-1729 Investor: Susan Morris (650) 225-6523 Biogen Idec Contacts: Media: Amy Brockelman (617) 914-6524 Investor: Eric Hoffman (617) 679-2812 GENENTECH AND BIOGEN IDEC ANNOUNCE POSITIVE RESULTS FROM A PHASE II TRIAL OF RITUXAN IN RELAPSING-REMITTING MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS SOUTH SAN FRANCISCO, Calif. and CAMBRIDGE, Mass. – August 28, 2006 – Genentech, Inc. (NYSE: DNA) and Biogen Idec, Inc. (Nasdaq: BIIB) announced today that a Phase II study of Rituxan® (Rituximab) for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) met its primary endpoint. The study of 104 patients showed a statistically significant reduction in the total number of gadolinium enhancing T1 lesions observed on serial MRI scans of the brain at weeks 12, 16, 20 and 24 in the Rituxan-treated group compared to placebo. Genentech and Biogen Idec will continue to analyze the study results and will submit the data for presentation at an upcoming medical meeting. “These initial results exceeded our expectations,” said Hal Barron, M.D., Genentech senior vice president, development and chief medical officer. “Showing a significant benefit at 24 weeks in this small Phase II trial supports our hypothesis that selective B-cell targeted therapy may play an important role in the treatment of MS.” - more - - 2 - “Biogen Idec is committed to offering multiple options for people living with MS, a devastating disease. We are very encouraged by these data and look forward to learning more about the potential of Rituxan as a therapy to treat MS,” said Alfred Sandrock, M.D., Ph.D., senior vice president, neurology research and development, Biogen Idec. -

Humankind 2.0: the Technologies of the Future 6. Biotech

Humankind 2.0: The Technologies of the Future 6. Biotech Piero Scaruffi, 2017 See http://www.scaruffi.com/singular/human20.html for the full text of this discussion A brief History of Biotech 1953: Discovery of the structure of the DNA 2 A brief History of Biotech 1969: Jon Beckwith isolates a gene 1973: Stanley Cohen and Herbert Boyer create the first recombinant DNA organism 1974: Waclaw Szybalski coins the term "synthetic biology” 1975: Paul Berg organizes the Asilomar conference on recombinant DNA 3 A brief History of Biotech 1976: Genentech is founded 1977: Fred Sanger invents a method for rapid DNA sequencing and publishes the first full DNA genome of a living being Janet Rossant creates a chimera combining two mice species 1980: Genentech’s IPO, first biotech IPO 4 A brief History of Biotech 1982: The first biotech drug, Humulin, is approved for sale (Eli Lilly + Genentech) 1983: Kary Mullis invents the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for copying genes 1986: Leroy Hood invents a way to automate gene sequencing 1986: Mario Capecchi performs gene editing on a mouse 1990: William French Anderson’s gene therapy 1990: First baby born via PGD (Alan Handyside’s lab) 5 A brief History of Biotech 1994: FlavrSavr Tomato 1994: Maria Jasin’s homing endonucleases for genome editing 1996: Srinivasan Chandrasegaran’s ZFN method for genome editing 1996: Ian Wilmut clones the first mammal, the sheep Dolly 1997: Dennis Lo detects fetal DNA in the mother’s blood 2000: George Davey Smith introduces Mendelian randomization 6 A brief History of Biotech -

Guide to Biotechnology 2008

guide to biotechnology 2008 research & development health bioethics innovate industrial & environmental food & agriculture biodefense Biotechnology Industry Organization 1201 Maryland Avenue, SW imagine Suite 900 Washington, DC 20024 intellectual property 202.962.9200 (phone) 202.488.6301 (fax) bio.org inform bio.org The Guide to Biotechnology is compiled by the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) Editors Roxanna Guilford-Blake Debbie Strickland Contributors BIO Staff table of Contents Biotechnology: A Collection of Technologies 1 Regenerative Medicine ................................................. 36 What Is Biotechnology? .................................................. 1 Vaccines ....................................................................... 37 Cells and Biological Molecules ........................................ 1 Plant-Made Pharmaceuticals ........................................ 37 Therapeutic Development Overview .............................. 38 Biotechnology Industry Facts 2 Market Capitalization, 1994–2006 .................................. 3 Agricultural Production Applications 41 U.S. Biotech Industry Statistics: 1995–2006 ................... 3 Crop Biotechnology ...................................................... 41 U.S. Public Companies by Region, 2006 ........................ 4 Forest Biotechnology .................................................... 44 Total Financing, 1998–2007 (in billions of U.S. dollars) .... 4 Animal Biotechnology ................................................... 45 Biotech -

Documenting the Biotechnology Industry in the San Francisco Bay Area

Documenting the Biotechnology Industry In the San Francisco Bay Area Robin L. Chandler Head, Archives and Special Collections UCSF Library and Center for Knowledge Management 1997 1 Table of Contents Project Goals……………………………………………………………………….p. 3 Participants Interviewed………………………………………………………….p. 4 I. Documenting Biotechnology in the San Francisco Bay Area……………..p. 5 The Emergence of An Industry Developments at the University of California since the mid-1970s Developments in Biotech Companies since mid-1970s Collaborations between Universities and Biotech Companies University Training Programs Preparing Students for Careers in the Biotechnology Industry II. Appraisal Guidelines for Records Generated by Scientists in the University and the Biotechnology Industry………………………. p. 33 Why Preserve the Records of Biotechnology? Research Records to Preserve Records Management at the University of California Records Keeping at Biotech Companies III. Collecting and Preserving Records in Biotechnology…………………….p. 48 Potential Users of Biotechnology Archives Approaches to Documenting the Field of Biotechnology Project Recommendations 2 Project Goals The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Library & Center for Knowledge Management and the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) are collaborating in a year-long project beginning in December 1996 to document the impact of biotechnology in the Bay Area. The collaborative effort is focused upon the development of an archival collecting model for the field of biotechnology to acquire original papers, manuscripts and records from selected individuals, organizations and corporations as well as coordinating with the effort to capture oral history interviews with many biotechnology pioneers. This project combines the strengths of the existing UCSF Biotechnology Archives and the UCB Program in the History of the Biological Sciences and Biotechnology and will contribute to an overall picture of the growth and impact of biotechnology in the Bay Area. -

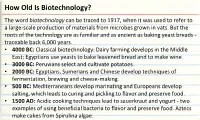

How Old Is Biotechnology? the Word Biotechnology Can Be Traced to 1917, When It Was Used to Refer to a Large-Scale Production of Materials from Microbes Grown in Vats

How Old Is Biotechnology? The word biotechnology can be traced to 1917, when it was used to refer to a large-scale production of materials from microbes grown in vats. But the roots of the technology are as familiar and as ancient as baking yeast breads - traceable back 6,000 years. • 4000 BC: Classical biotechnology: Dairy farming develops in the Middle East; Egyptians use yeasts to bake leavened bread and to make wine. • 3000 BC: Peruvians select and cultivate potatoes. • 2000 BC: Egyptians, Sumerians and Chinese develop techniques of fermentation, brewing and cheese-making. • 500 BC: Mediterraneans develop marinating and Europeans develop salting, which leads to curing and pickling to flavor and preserve food. • 1500 AD: Acidic cooking techniques lead to sauerkraut and yogurt - two examples of using beneficial bacteria to flavor and preserve food. Aztecs make cakes from Spirulina algae. How Old Is Biotechnology? (continued) • 1859: On the Origin of Species - English naturalist Charles Darwin's theory of evolution - is published in London. • 1861: French chemist Louis Pasteur develops pasteurization - preserving food by heating it to destroy harmful microbes. • 1865: Austrian botanist and monk Gregor Mendel describes his experiments in heredity, founding the field of genetics. • 1879: William James Beal develops the first experimental hybrid corn • 1910: American biologist Thomas Hunt Morgan discovers that genes are located on chromosomes. • 1928: F. Griffith discovers genetic transformation - genes can transfer from one strain of bacteria to another. • 1941: Danish microbiologist A. Jost coins the term genetic engineering in a lecture on sexual reproduction in yeast. How Old Is Biotechnology? (continued) • 1943: Oswald Avery, Colin MacLead and Maclyn McCarty use bacteria to show that DNA carries the cell's genetic information. -

SHALOM NWODO CHINEDU from Evolution to Revolution

Covenant University Km. 10 Idiroko Road, Canaan Land, P.M.B 1023, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria Website: www.covenantuniversity.edu.ng TH INAUGURAL 18 LECTURE From Evolution to Revolution: Biochemical Disruptions and Emerging Pathways for Securing Africa's Future SHALOM NWODO CHINEDU INAUGURAL LECTURE SERIES Vol. 9, No. 1, March, 2019 Covenant University 18th Inaugural Lecture From Evolution to Revolution: Biochemical Disruptions and Emerging Pathways for Securing Africa's Future Shalom Nwodo Chinedu, Ph.D Professor of Biochemistry (Enzymology & Molecular Genetics) Department of Biochemistry Covenant University, Ota Media & Corporate Affairs Covenant University, Km. 10 Idiroko Road, Canaan Land, P.M.B 1023, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria Tel: +234-8115762473, 08171613173, 07066553463. www.covenantuniversity.edu.ng Covenant University Press, Km. 10 Idiroko Road, Canaan Land, P.M.B 1023, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria ISSN: 2006-0327 Public Lecture Series. Vol. 9, No.1, March, 2019 Shalom Nwodo Chinedu, Ph.D Professor of Biochemistry (Enzymology & Molecular Genetics) Department of Biochemistry Covenant University, Ota From Evolution To Revolution: Biochemical Disruptions and Emerging Pathways for Securing Africa's Future THE FOUNDATION 1. PROTOCOL The Chancellor and Chairman, Board of Regents of Covenant University, Dr David O. Oyedepo; the Vice-President (Education), Living Faith Church World-Wide (LFCWW), Pastor (Mrs) Faith A. Oyedepo; esteemed members of the Board of Regents; the Vice- Chancellor, Professor AAA. Atayero; the Deputy Vice-Chancellor; the