Mucopolysaccharidosis VII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epidemiology of Mucopolysaccharidoses Update

diagnostics Review Epidemiology of Mucopolysaccharidoses Update Betul Celik 1,2 , Saori C. Tomatsu 2 , Shunji Tomatsu 1 and Shaukat A. Khan 1,* 1 Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, DE 19803, USA; [email protected] (B.C.); [email protected] (S.T.) 2 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +302-298-7335; Fax: +302-651-6888 Abstract: Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) are a group of lysosomal storage disorders caused by a lysosomal enzyme deficiency or malfunction, which leads to the accumulation of glycosaminoglycans in tissues and organs. If not treated at an early stage, patients have various health problems, affecting their quality of life and life-span. Two therapeutic options for MPS are widely used in practice: enzyme replacement therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, early diagnosis of MPS is crucial, as treatment may be too late to reverse or ameliorate the disease progress. It has been noted that the prevalence of MPS and each subtype varies based on geographic regions and/or ethnic background. Each type of MPS is caused by a wide range of the mutational spectrum, mainly missense mutations. Some mutations were derived from the common founder effect. In the previous study, Khan et al. 2018 have reported the epidemiology of MPS from 22 countries and 16 regions. In this study, we aimed to update the prevalence of MPS across the world. We have collected and investigated 189 publications related to the prevalence of MPS via PubMed as of December 2020. In total, data from 33 countries and 23 regions were compiled and analyzed. -

Open CR-Thesis-Final-Final.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School IDENTIFICATION OF GENETIC FACTORS THAT AFFECT NEURONAL PATTERNING, FUNCTION, AND DISEASE IN DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER A Dissertation in Biochemistry, Microbiology, and Molecular Biology by Claire Elizabeth Reynolds Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 The dissertation of Claire Elizabeth Reynolds was reviewed and approved* by the following: Scott B Selleck Professor of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Dissertation Co-Advisor Chair of Committee Santhosh Girirajan Assistant Professor of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Assistant Professor of Anthropology Dissertation Co-Advisor Joseph Reese Professor of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Marylyn Ritchie Director, Center for Systems Genomics Director, Biomedical & Translational Informatics Program of Geisinger Research Professor of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Richard Ordway Professor of Molecular Neuroscience and Genetics Wendy Hanna-Rose Associate Professor of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Interim Head of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans (HSPGs) are required for normal synaptic development at the Drosophila melanogaster larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ). When enzymes required for biosynthesis of HSPGs are inhibited through mutations of RNA interference, a variety of morphological and electrophysiological defects are observed at the NMJ. These defects included changes in the post-synaptic specialization of the muscle (the SSR), loss of mitochondria from the sub-synaptic cytosol, and abnormal mitochondrial morphology. Identification of autophagic regulation as the mechanism by which HSPGs influenced synaptic properties was the foundation of this dissertation. The present work more fully characterizes the influence of HSPG function on autophagic markers in muscle tissue. -

Pathophysiology of Mucopolysaccharidosis

Pathophysiology of Mucopolysaccharidosis Dr. Christina Lampe, MD The Center for Rare Diseases, Clinics for Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine Helios Dr. Horst Schmidt Kliniken, Wiesbaden, Germany Inborn Errors of Metabolism today - more than 500 diseases (~10 % of the known genetic diseases) 5000 genetic diseases - all areas of metabolism involved - vast majority are recessive conditions 500 metabolic disorders - individually rare or very rare - overall frequency around 1:800 50 LSD (similar to Down syndrome) LSDs: 1: 5.000 live births MPS: 1: 25.000 live births 7 MPS understanding of pathophysiology and early diagnosis leading to successful therapy for several conditions The Lysosomal Diseases (LSD) TAY SACHS DIS. 4% WOLMAN DIS. ASPARTYLGLUCOSAMINURIA SIALIC ACID DIS. SIALIDOSIS CYSTINOSIS 4% SANDHOFF DIS. 2% FABRY DIS. 7% POMPE 5% NIEMANN PICK C 4% GAUCHER DIS. 14% Mucopolysaccharidosis NIEMANN PICK A-B 3% MULTIPLE SULPH. DEF. Mucolipidosis MUCOLIPIDOSIS I-II 2% Sphingolipidosis MPSVII Oligosaccharidosis GM1 GANGLIOSIDOSIS 2% MPSVI Neuronale Ceroid Lipofuszinois KRABBE DIS. 5% MPSIVA others MPSIII D A-MANNOSIDOSIS MPSIII C MPSIIIB METACHROMATIC LEUKOD. 8% MPS 34% MPSIIIA MPSI MPSII Initial Description of MPS Charles Hunter, 1917: “A Rare Disease in Two Brothers” brothers: 10 and 8 years hearing loss dwarfism macrocephaly cardiomegaly umbilical hernia joint contractures skeletal dysplasia death at the age of 11 and 16 years Description of the MPS Types... M. Hunter - MPS II (1917) M. Hurler - MPS I (1919) M. Morquio - MPS IV (1929) M. Sanfilippo - MPS III (1963) M. Maroteaux-Lamy - MPS IV (1963) M. Sly - MPS VII (1969) M. Scheie - MPS I (MPS V) (1968) M. Natowicz - MPS IX (1996) The Lysosome Lysosomes are.. -

Enzyme-Replacement Therapy in Mucopolysaccharidoses with A

Enzyme-replacement Therapy in Mucopolysaccharidoses with a Specific Focus on MPS VI Enzym vervangende therapie in de mucopolysaccharidosen met specifieke aandacht voor MPS VI proefschrift.indb 1 27-8-2013 16:01:52 Financial support for this project was obtained from ZonMw (the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development), the Dutch TI Pharma initiative “Sustainable Orphan Drug Development through Registries and Monitoring”, European Union, 7th Framework programme EUCLYD – European Consortium for Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Printing of this thesis was financially supported by: BioMarin Pharmaceutical Shire International Licensing BV ISBN: 978-90-6464-700-0 Lay-out: Chris Bor Medical Photography and Illustration, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Cover design: Anne Bonthuis Druk: GVO | Ponsen & Looijen, Ede © Marion Brands, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or means without permission of the author, or, when appropriate, of the publishers of the publications. proefschrift.indb 2 27-8-2013 16:01:53 Enzyme-replacement Therapy in Mucopolysaccharidoses with a Specific Focus on MPS VI Enzym vervangende therapie in de mucopolysaccharidosen met specifieke aandacht voor MPS VI Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.G. Schmidt en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op dinsdag 15 oktober 2013 om 15:30 uur. Marion Maria Mathilde Geertruida Brands geboren te Heerlen proefschrift.indb 3 27-8-2013 16:01:53 Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof.dr. A.T. -

Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly

277 Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly KellenD.Winden,MD,PhD1 Christopher J. Yuskaitis, MD, PhD1 Annapurna Poduri, MD, MPH2 1 Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Address for correspondence Annapurna Poduri, Epilepsy Genetics Massachusetts Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2 Epilepsy Genetics Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Department of Neurology, Fegan 9, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Electrophysiology, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (e-mail: [email protected]). Semin Neurol 2015;35:277–287. Abstract Megalencephaly is a developmental disorder characterized by brain overgrowth secondary to increased size and/or numbers of neurons and glia. These disorders can be divided into metabolic and developmental categories based on their molecular etiologies. Metabolic megalencephalies are mostly caused by genetic defects in cellular metabolism, whereas developmental megalencephalies have recently been shown to be caused by alterations in signaling pathways that regulate neuronal replication, growth, and migration. These disorders often lead to epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and Keywords behavioral problems; specific disorders have associations with overgrowth or abnor- ► megalencephaly malities in other tissues. The molecular underpinnings of many of these disorders are ► hemimegalencephaly now understood, providing insight into how dysregulation of critical pathways leads to ► -

Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases Collection

Marche des Maladies Rares – Alliance Maladies Rares Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases collection DecemberOctober 2013 2009 List of rare diseases and synonyms Listed in alphabetical order www.orpha.net 20102206 Rare diseases listed in alphabetical order ORPHA ORPHA ORPHA Disease name Disease name Disease name Number Number Number 289157 1-alpha-hydroxylase deficiency 309127 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase 228384 5q14.3 microdeletion syndrome deficiency 293948 1p21.3 microdeletion syndrome 314655 5q31.3 microdeletion syndrome 939 3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria 1606 1p36 deletion syndrome 228415 5q35 microduplication syndrome 2616 3M syndrome 250989 1q21.1 microdeletion syndrome 96125 6p subtelomeric deletion syndrome 2616 3-M syndrome 250994 1q21.1 microduplication syndrome 251046 6p22 microdeletion syndrome 293843 3MC syndrome 250999 1q41q42 microdeletion syndrome 96125 6p25 microdeletion syndrome 6 3-methylcrotonylglycinuria 250999 1q41-q42 microdeletion syndrome 99135 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase 67046 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 1 deficiency 238769 1q44 microdeletion syndrome 111 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 2 13 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase 976 2,8 dihydroxyadenine urolithiasis deficiency 67047 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 3 869 2A syndrome 75857 6q terminal deletion 67048 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 4 79154 2-aminoadipic 2-oxoadipic aciduria 171829 6q16 deletion syndrome 66634 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 5 19 2-hydroxyglutaric acidemia 251056 6q25 microdeletion syndrome 352328 3-methylglutaconic -

![Hurler Syndrome (Mucopolysaccharidosis Type 1) in a Young Female Patient [Version 1; Peer Review: 3 Approved with Reservations]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5921/hurler-syndrome-mucopolysaccharidosis-type-1-in-a-young-female-patient-version-1-peer-review-3-approved-with-reservations-825921.webp)

Hurler Syndrome (Mucopolysaccharidosis Type 1) in a Young Female Patient [Version 1; Peer Review: 3 Approved with Reservations]

F1000Research 2020, 9:367 Last updated: 06 AUG 2021 CASE REPORT Case Report: Hurler syndrome (Mucopolysaccharidosis Type 1) in a young female patient [version 1; peer review: 3 approved with reservations] Sadaf Saleem Sheikh1, Dipak Kumar Yadav 2, Ayesha Saeed3 1Punjab Medical College, Faisalabad, Pakistan 2Nobel Medical College Teaching Hospital, Biratnagar, Nepal 3The Children’s Hospital, Institute of Child Health, Faisalabad, Pakistan v1 First published: 15 May 2020, 9:367 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.23532.1 Latest published: 15 May 2020, 9:367 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.23532.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract Hurler syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of 1 2 3 mucopolysaccharide metabolism. Here, we present the case of a young female patient who presented with features of respiratory version 1 distress. In addition, the patient had gingival hypertrophy, spaced 15 May 2020 report report report dentition, misaligned eruptive permanent dentition, microdontia, coarse facial features, low set ears, depressed nasal bridge, distended 1. Sanghamitra Satpathi , Hi-Tech Medical abdomen, pectus carinatum, umbilical hernia and J-shaped Sella Turcica on an X-ray of the skull. A diagnosis of Hurler syndrome College and Hospital, Rourkela, India (Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I) was made. The patient was kept on ventilator support from the third day; however, she died on the fifth 2. Alla N. Semyachkina , Research and day of admission. Enzyme replacement modality of treatment can Clinical Institute for Pediatrics of the Pirogov increase a patient's survival rate if an early diagnosis can be made. To Russian National Research Medical the best of our knowledge, only a few cases of Hurler syndrome have been reported in Pakistan. -

Medical Genetics and Genomic Medicine in the United States of America

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by George Washington University: Health Sciences Research Commons (HSRC) Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University Health Sciences Research Commons Pediatrics Faculty Publications Pediatrics 7-1-2017 Medical genetics and genomic medicine in the United States of America. Part 1: history, demographics, legislation, and burden of disease. Carlos R Ferreira George Washington University Debra S Regier George Washington University Donald W Hadley P Suzanne Hart Maximilian Muenke Follow this and additional works at: https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/smhs_peds_facpubs Part of the Genetics and Genomics Commons APA Citation Ferreira, C., Regier, D., Hadley, D., Hart, P., & Muenke, M. (2017). Medical genetics and genomic medicine in the United States of America. Part 1: history, demographics, legislation, and burden of disease.. Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine, 5 (4). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.318 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pediatrics at Health Sciences Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pediatrics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Health Sciences Research Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENETICS AND GENOMIC MEDICINE AROUND THE WORLD Medical genetics and genomic medicine in the United States of America. Part 1: history, demographics, legislation, and burden of disease Carlos R. Ferreira1,2 , Debra S. Regier2, Donald W. Hadley1, P. Suzanne Hart1 & Maximilian Muenke1 1National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 2Rare Disease Institute, Children’s National Health System, Washington, District of Columbia Correspondence Carlos R. -

18 the Mucopolysaccharidoses J

18 The Mucopolysaccharidoses J. Edward Wraith, Joe T.R. Clarke 18.1 Introduction The disorders described in this chapter are associated with a progressive ac- cumulation of glycosaminoglycans (GAG) within the cells of various organs, ultimately compromising their function. The major sites of disease differ de- pending on the specific enzyme deficiency, and therefore the clinical presenta- tion and approach to therapy is different for the various disease subtypes. Patients with the severe form of mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS I; Hurler dis- ease, MPS IH), MPS II (Hunter disease), and MPS VI (Maroteaux-Lamy disease) generally present with facial dysmorphism and persistent respiratory disease in the early years of life. Many patients will have undergone surgical procedures for recurrent otitis media and hernia repair before the diagnosis is established. Infants with MPS III (Sanfilippo A, B, C, or D disease) present with learning difficulties and then develop a profound behavioral disturbance. The behavior disorder is characteristic and often leads to the diagnosis. Somatic features are mild in these patients. Children with MPS IVA (Morquio disease, type A) have normal cognitive functions, but are affected by severe spondoepiphyseal dysplasia, which in most patients leads to extreme short stature, deformity of the chest, marked shortening and instability of the neck, and joint laxity. MPS IVB(Morquiodisease,typeB)ismuchmorevariableinitseffects.Ithassome features of the skeletal dysplasia of MPS IVA; however, most patients also have learning difficulties. MPS VII (Sly disease) often presents as nonimmune hy- drops fetalis. Those patients who survive or who present later resemble patients with MPS IH with respect to clinical phenotype and supportive management. -

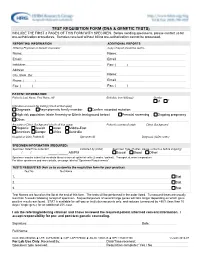

Test Requisition Form (Dna & Genetic Tests)

TEST REQUISITION FORM (DNA & GENETIC TESTS) INCLUDE THE FIRST 3 PAGES OF THIS FORM WITH SPECIMEN. Before sending specimens, please contact us for pre-authorization procedures. Samples received without billing pre-authorization cannot be processed. REPORTING INFORMATION ADDITIONAL REPORTS Ordering Physician or Genetic Counselor Copy of report should be sent to Name: Name: Email: Email: Institution: Fax: ( ) Address: City, State, Zip: Name: Phone: ( ) Email: Fax: ( ) Fax: ( ) PATIENT INFORMATION Patient's Last Name, First Name, MI Birthdate (mm/dd/yyyy) Gender M F Indication or reason for testing (check all that apply) Diagnosis Asymptomatic family member Confirm recorded mutation: High risk population (state Ancestry or Ethnic background below) Prenatal screening Ongoing pregnancy Other: Ancestry or Ethnic Background (check all that apply) Patient's country of origin Ethnic Background Hispanic Jewish Asian Middle-East Americas Europe Africa Australia Hospital or Clinic Patient ID Specimen ID Diagnosis (ICD9 codes) SPECIMEN INFORMATION (REQUIRED) Specimen Date/Time Collected Collected by (initial) Specimen Type (If other, please contact us before shipping) / / _____:_____ AM/PM Buccal Blood Other: Specimen may be submitted as whole blood or buccal epithelial cells (2 swabs / patient). Transport at room temperature. For other specimens and more details, see page labeled "Specimen Requirements". TESTS REQUESTED (Ask us to customize the requisition form for your practice) Test No. Test Name 1. Stat 2. Stat 3. Stat Test Names are found on the list at the end of this form. The tests will be performed in the order listed. Turnaround times are usually less than 5 weeks following receipt of specimen. Sequential panels of several large genes will take longer depending on which gene positive results are found. -

Anesthetic Considerations and Clinical Manifestations 243

MUCOPOLYSACCHARIDOSES: ANESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS 243 MUCOPOLYSACCHARIDOSES: ANESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS * ** *** JERMALE A. SAM , AMIR R. BALUCH , RASHID S. NIAZ , *** **** LINDSEY LONADIER AND ALAN D. KAYE Abstract Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) is a group of genetic disorders that presents challenges during anesthetic care and in particular difficulty with airway management. Patients should be managed by experienced anesthesiologists at centers that are familiar with these types of conditions. Rarely encountered disease states have been identified as important topics in the continuing education of clinical anesthesiologists. This review will define MPS, describe the pathophysiology of MPS, describe how patients with this rare lysosomal storage disorders have dysfunction of tissues, cite the incidence of MPS, list the clinical manifestations and specific problems associated with the administration of anesthesia to patients with MPS, present treatment options for patients with MPS, define appropriate preoperative evaluation and perioperative management of these patients, including, to anticipate potential postoperative airway problems. Introduction Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) are a group of rare genetic lysosomal storage disorders characterized by the deficiency in or complete lack of necessary lysosomal enzymes required for the stepwise breakdown of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs, also known as mucopolysaccharidoses)1-5. Consequently, fragments of GAGs accumulate intracellularly in the lysosome resulting in cellular enlargement causing disruption/dysfunction of structure and function of tissues. This process leads to numerous clinical abnormalities. Incidence of all types of MPS is reported to be between 1in 10,000 to 1 in 30,000 live births and are transmitted autosomal recessive except for MPS II which is X-linked1,4,5. Pathophysiology Glycosaminoglycans are long-chain complex carbohydrates consisting of repeating sulfated acidic and amino sugar disaccharide units. -

Long-Term Follow-Up Posthematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in a Japanese Patient with Type-VII Mucopolysaccharidosis

diagnostics Case Report Long-Term Follow-up Posthematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in a Japanese Patient with Type-VII Mucopolysaccharidosis Kenji Orii 1,*, Yasuyuki Suzuki 2 , Shunji Tomatsu 1,3,4, Tadao Orii 1 and Toshiyuki Fukao 1 1 Department of Pediatrics, Gifu University Graduate School of Medicine, Yanagido 1-1, Gifu 501-1194, Japan; [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (T.O.); [email protected] (T.F.) 2 Medical Education Development Center, Gifu University, Yanagido 1-1, Gifu 501-1194, Japan; [email protected] 3 Nemours/Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, 1600 Rockland Rd., Wilmington, DE 19803, USA 4 Department of Pediatrics, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19144, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-58-230-6386 Received: 15 January 2020; Accepted: 13 February 2020; Published: 16 February 2020 Abstract: The effectiveness of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for type-VII mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS VII, Sly syndrome) remains controversial, although recent studies have shown that it has a clinical impact. In 1998, Yamada et al. reported the first patient with MPS VII, who underwent HSCT at 12 years of age. Here, we report the results of a 22-year follow-up of that patient post-HSCT, who harbored the p.Ala619Val mutation associated with an attenuated phenotype. The purpose of this study was to evaluate changes in physical symptoms, the activity of daily living (ADL), and the intellectual status in the 34-year-old female MPS VII patient post-HSCT, and to prove the long-term effects of HSCT in MPS VII.