The Reclassification of Asteroids from Planets to Non-Planets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions

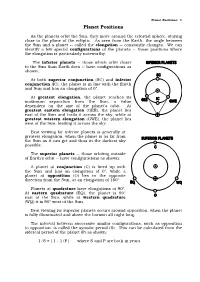

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions As the planets orbit the Sun, they move around the celestial sphere, staying close to the plane of the ecliptic. As seen from the Earth, the angle between the Sun and a planet -- called the elongation -- constantly changes. We can identify a few special configurations of the planets -- those positions where the elongation is particularly noteworthy. The inferior planets -- those which orbit closer INFERIOR PLANETS to the Sun than Earth does -- have configurations as shown: SC At both superior conjunction (SC) and inferior conjunction (IC), the planet is in line with the Earth and Sun and has an elongation of 0°. At greatest elongation, the planet reaches its IC maximum separation from the Sun, a value GEE GWE dependent on the size of the planet's orbit. At greatest eastern elongation (GEE), the planet lies east of the Sun and trails it across the sky, while at greatest western elongation (GWE), the planet lies west of the Sun, leading it across the sky. Best viewing for inferior planets is generally at greatest elongation, when the planet is as far from SUPERIOR PLANETS the Sun as it can get and thus in the darkest sky possible. C The superior planets -- those orbiting outside of Earth's orbit -- have configurations as shown: A planet at conjunction (C) is lined up with the Sun and has an elongation of 0°, while a planet at opposition (O) lies in the opposite direction from the Sun, at an elongation of 180°. EQ WQ Planets at quadrature have elongations of 90°. -

Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur

Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur To cite this version: Alex Soumbatov-Gur. Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution. [Research Report] Karpov institute of physical chemistry. 2019. hal-02147461 HAL Id: hal-02147461 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02147461 Submitted on 4 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur The moons are confirmed to be ejected parts of Mars’ crust. After explosive throwing out as cone-like rocks they plastically evolved with density decays and materials transformations. Their expansion evolutions were accompanied by global ruptures and small scale rock ejections with concurrent crater formations. The scenario reconciles orbital and physical parameters of the moons. It coherently explains dozens of their properties including spectra, appearances, size differences, crater locations, fracture symmetries, orbits, evolution trends, geologic activity, Phobos’ grooves, mechanism of their origin, etc. The ejective approach is also discussed in the context of observational data on near-Earth asteroids, main belt asteroids Steins, Vesta, and Mars. The approach incorporates known fission mechanism of formation of miniature asteroids, logically accounts for its outliers, and naturally explains formations of small celestial bodies of various sizes. -

Flower Constellation Optimization and Implementation

FLOWER CONSTELLATION OPTIMIZATION AND IMPLEMENTATION A Dissertation by CHRISTIAN BRUCCOLERI Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2007 Major Subject: Aerospace Engineering FLOWER CONSTELLATION OPTIMIZATION AND IMPLEMENTATION A Dissertation by CHRISTIAN BRUCCOLERI Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Daniele Mortari Committee Members, John L. Junkins Thomas C. Pollock J. Maurice Rojas Head of Department, Helen Reed December 2007 Major Subject: Aerospace Engineering iii ABSTRACT Flower Constellation Optimization and Implementation. (December 2007) Christian Bruccoleri, M.S., Universit´a di Roma - La Sapienza Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Daniele Mortari Satellite constellations provide the infrastructure to implement some of the most im- portant global services of our times both in civilian and military applications, ranging from telecommunications to global positioning, and to observation systems. Flower Constellations constitute a set of satellite constellations characterized by periodic dynamics. They have been introduced while trying to augment the existing design methodologies for satellite constellations. The dynamics of a Flower Constellation identify a set of implicit rotating reference frames on which the satellites follow the same closed-loop relative trajectory. In particular, when one of these rotating refer- ence frames is “Planet Centered, Planet Fixed”, then all the orbits become compatible (or resonant) with the planet; consequently, the projection of the relative path on the planet results in a repeating ground track. The satellite constellations design methodology currently most utilized is the Walker Delta Pattern or, more generally, Walker Constellations. -

Chapter 9: the Origin and Evolution of the Moon and Planets

Chapter 9 THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF THE MOON AND PLANETS 9.1 In the Beginning The age of the universe, as it is perceived at present, is perhaps as old as 20 aeons so that the formation of the solar system at about 4.5 aeons is a comparatively youthful event in this stupendous extent of time [I]. Thevisible portion of the universe consists principally of about 10" galaxies, which show local marked irregularities in distribution (e.g., Virgo cluster). The expansion rate (Hubble Constant) has values currently estimated to lie between 50 and 75 km/sec/MPC [2]. The reciprocal of the constant gives ages ranging between 13 and 20 aeons but there is uncertainty due to the local perturbing effects of the Virgo cluster of galaxies on our measurement of the Hubble parameter [I]. The age of the solar system (4.56 aeons), the ages of old star clusters (>10" years) and the production rates of elements all suggest ages for the galaxy and the observable universe well in excess of 10" years (10 aeons). The origin of the presently observable universe is usually ascribed, in current cosmologies, to a "big bang," and the 3OK background radiation is often accepted as proof of the correctness of the hypothesis. Nevertheless, there are some discrepancies. The observed ratio of hydrogen to helium which should be about 0.25 in a "big-bang" scenario may be too high. The distribution of galaxies shows much clumping, which would indicate an initial chaotic state [3], and there are variations in the spectrum of the 3OK radiation which are not predicted by the theory. -

Occultation Newsletter Volume 8, Number 4

Volume 12, Number 1 January 2005 $5.00 North Am./$6.25 Other International Occultation Timing Association, Inc. (IOTA) In this Issue Article Page The Largest Members Of Our Solar System – 2005 . 4 Resources Page What to Send to Whom . 3 Membership and Subscription Information . 3 IOTA Publications. 3 The Offices and Officers of IOTA . .11 IOTA European Section (IOTA/ES) . .11 IOTA on the World Wide Web. Back Cover ON THE COVER: Steve Preston posted a prediction for the occultation of a 10.8-magnitude star in Orion, about 3° from Betelgeuse, by the asteroid (238) Hypatia, which had an expected diameter of 148 km. The predicted path passed over the San Francisco Bay area, and that turned out to be quite accurate, with only a small shift towards the north, enough to leave Richard Nolthenius, observing visually from the coast northwest of Santa Cruz, to have a miss. But farther north, three other observers video recorded the occultation from their homes, and they were fortuitously located to define three well- spaced chords across the asteroid to accurately measure its shape and location relative to the star, as shown in the figure. The dashed lines show the axes of the fitted ellipse, produced by Dave Herald’s WinOccult program. This demonstrates the good results that can be obtained by a few dedicated observers with a relatively faint star; a bright star and/or many observers are not always necessary to obtain solid useful observations. – David Dunham Publication Date for this issue: July 2005 Please note: The date shown on the cover is for subscription purposes only and does not reflect the actual publication date. -

Origin and Evolution of Trojan Asteroids 725

Marzari et al.: Origin and Evolution of Trojan Asteroids 725 Origin and Evolution of Trojan Asteroids F. Marzari University of Padova, Italy H. Scholl Observatoire de Nice, France C. Murray University of London, England C. Lagerkvist Uppsala Astronomical Observatory, Sweden The regions around the L4 and L5 Lagrangian points of Jupiter are populated by two large swarms of asteroids called the Trojans. They may be as numerous as the main-belt asteroids and their dynamics is peculiar, involving a 1:1 resonance with Jupiter. Their origin probably dates back to the formation of Jupiter: the Trojan precursors were planetesimals orbiting close to the growing planet. Different mechanisms, including the mass growth of Jupiter, collisional diffusion, and gas drag friction, contributed to the capture of planetesimals in stable Trojan orbits before the final dispersal. The subsequent evolution of Trojan asteroids is the outcome of the joint action of different physical processes involving dynamical diffusion and excitation and collisional evolution. As a result, the present population is possibly different in both orbital and size distribution from the primordial one. No other significant population of Trojan aster- oids have been found so far around other planets, apart from six Trojans of Mars, whose origin and evolution are probably very different from the Trojans of Jupiter. 1. INTRODUCTION originate from the collisional disruption and subsequent reaccumulation of larger primordial bodies. As of May 2001, about 1000 asteroids had been classi- A basic understanding of why asteroids can cluster in fied as Jupiter Trojans (http://cfa-www.harvard.edu/cfa/ps/ the orbit of Jupiter was developed more than a century lists/JupiterTrojans.html), some of which had only been ob- before the first Trojan asteroid was discovered. -

Guide to the Extended Versions of MPC Data Files Based on the MPCORB Format

Guide to the Extended Versions of MPC Data Files Based on the MPCORB Format Last updated: 2016/04/19 by J.L. Galache Introduction The Minor Planet Center (MPC) has been providing the orbits of minor planets in the form of a file, MPCORB.DAT, since the mid '90s (1990s, not 1890s). Back then there were only a few thousand known asteroids, compared to the several hundred thousand of today, so a flat text file was the appropriate way to circulate these data. It was also a time when most orbit computations were programmed in Fortran, which ingested data no other way. MPCORB.DAT has therefore always been, and continues to be, a fixed-width file (see Table 1 for the current format description1). In fact, all original data files available on the MPC website are flat text files (even the orbits files provided for planetarium-type/sky simulation software packages are simply text files of varying format2). In the early years of the 2010s, possibly due to the rising popularity of the scripting language Python amongst astronomers, and an increased interest from developers wanting to write asteroid-themed tools, requests were received to provide data in other, easier to parse formats, e.g., JSON, CSV, SQL, etc. At the same time, astronomers and developers alike wanted more information than was currently been provided in MPCORB.DAT; information that did exist on the MPC website in other, often hard to find, files. Here was an opportunity to add some new data to existing files, while also making them available in other formats. -

1 Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects

Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects - a Review Renu Malhotra Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Email: [email protected] Abstract Our understanding of the history of the solar system has undergone a revolution in recent years, owing to new theoretical insights into the origin of Pluto and the discovery of the Kuiper belt and its rich dynamical structure. The emerging picture of dramatic orbital migration of the planets driven by interaction with the primordial Kuiper belt is thought to have produced the final solar system architecture that we live in today. This paper gives a brief summary of this new view of our solar system's history, and reviews the astronomical evidence in the resonant populations of the Kuiper belt. Introduction Lying at the edge of the visible solar system, observational confirmation of the existence of the Kuiper belt came approximately a quarter-century ago with the discovery of the distant minor planet (15760) Albion (formerly 1992 QB1, Jewitt & Luu 1993). With the clarity of hindsight, we now recognize that Pluto was the first discovered member of the Kuiper belt. The current census of the Kuiper belt includes more than 2000 minor planets at heliocentric distances between ~30 au and ~50 au. Their orbital distribution reveals a rich dynamical structure shaped by the gravitational perturbations of the giant planets, particularly Neptune. Theoretical analysis of these structures has revealed a remarkable dynamic history of the solar system. The story is as follows (see Fernandez & Ip 1984, Malhotra 1993, Malhotra 1995, Fernandez & Ip 1996, and many subsequent works). -

The Orbital Distribution of Near-Earth Objects Inside Earth’S Orbit

Icarus 217 (2012) 355–366 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus The orbital distribution of Near-Earth Objects inside Earth’s orbit ⇑ Sarah Greenstreet a, , Henry Ngo a,b, Brett Gladman a a Department of Physics & Astronomy, 6224 Agricultural Road, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada b Department of Physics, Engineering Physics, and Astronomy, 99 University Avenue, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada article info abstract Article history: Canada’s Near-Earth Object Surveillance Satellite (NEOSSat), set to launch in early 2012, will search for Received 17 August 2011 and track Near-Earth Objects (NEOs), tuning its search to best detect objects with a < 1.0 AU. In order Revised 8 November 2011 to construct an optimal pointing strategy for NEOSSat, we needed more detailed information in the Accepted 9 November 2011 a < 1.0 AU region than the best current model (Bottke, W.F., Morbidelli, A., Jedicke, R., Petit, J.M., Levison, Available online 28 November 2011 H.F., Michel, P., Metcalfe, T.S. [2002]. Icarus 156, 399–433) provides. We present here the NEOSSat-1.0 NEO orbital distribution model with larger statistics that permit finer resolution and less uncertainty, Keywords: especially in the a < 1.0 AU region. We find that Amors = 30.1 ± 0.8%, Apollos = 63.3 ± 0.4%, Atens = Near-Earth Objects 5.0 ± 0.3%, Atiras (0.718 < Q < 0.983 AU) = 1.38 ± 0.04%, and Vatiras (0.307 < Q < 0.718 AU) = 0.22 ± 0.03% Celestial mechanics Impact processes of the steady-state NEO population. -

The Minor Planets

The Minor Planets Swinburne Astronomy Online 3D PDF c SAO 2012 The Minor Planets c Swinburne Astronomy Online 2012 1 Description 1.1 Minor planets Our view of the Solar System has changed dramatically over the past 15 years with the discovery of new classes of small bodies. Mi- nor planets are another name for asteroids, or celestial bodies that orbit the Sun that are not otherwise classed as planets or comets. Generally, minor planets are relatively small rocky bodies, while comets are icy bodies that become active when their orbits carry them close to the Sun. (An \active" comet exhibits a large coma and a long tail.) The minor planets can be classified by their orbital characteristics. In this 3D PDF, we have included 5 classes of minor planets: (1) the Near Earth Asteroids (NEAs), (2) the main belt asteroids, (3) the Trojan asteroids of Jupiter, (4) the Centaurs, and (5) the Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs). The dataset used comes from the Minor Planets Centre. As of 19 November 2012, there were 9,346 NEAs (comprising 732 Atens, 4686 Apollos and 3928 Amors); 581,613 main belt asteroids; 5,407 jovian Trojans; 330 Centaurs; and 1,150 TNOs. (Note than in this 3D PDF, we have only included 11,678 main belt asteroids.) • The Near Earth Asteroids have perihelion distances of less than 1.3 AU, and include the following sub-classes: { Atens have aphelion distances greater than 0.983 AU, and semi-major axes less than 1 AU { Apollos have perihelion distances less than 1.017 AU, and semi-major axes greater than 1 AU { Amors have perihelion distances between 1.017 and 1.3 AU and semi-major axes greater than 1 AU • The main belt asteroids reside between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, with most of the asteroids orbiting between about 2.1 AU and 3.3 AU. -

Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: a Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 | Asifa

dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 1 Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: A Chronology ofDeep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 |Asif A.Siddiqi National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA SP-2002-4524 A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 Asif A. Siddiqi NASA SP-2002-4524 Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 2 Cover photo: A montage of planetary images taken by Mariner 10, the Mars Global Surveyor Orbiter, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2, all managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Included (from top to bottom) are images of Mercury, Venus, Earth (and Moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and its Moon, and Mars) and the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) are roughly to scale to each other. NASA SP-2002-4524 Deep Space Chronicle A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 ASIF A. SIDDIQI Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 June 2002 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations NASA History Office Washington, DC 20546-0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siddiqi, Asif A., 1966 Deep space chronicle: a chronology of deep space and planetary probes, 1958-2000 / by Asif A. Siddiqi. p.cm. – (Monographs in aerospace history; no. 24) (NASA SP; 2002-4524) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Space flight—History—20th century. I. Title. II. Series. III. NASA SP; 4524 TL 790.S53 2002 629.4’1’0904—dc21 2001044012 Table of Contents Foreword by Roger D. -

EJSM Origins White Document Recommendations by the Origins Working Group for EJSM Mission – JGO and JEO Spacecrafts

EJSM ORIGINS WORKING GROUP EJSM Origins White Document Recommendations by the Origins Working Group for EJSM Mission – JGO and JEO spacecrafts A. Coradini, D. Gautier, T. Guillot, G. Schubert, B. Moore, D. Turrini and H. J. Waite Document Type: Scientific Report Status: Final Version Revision: 4 Issued on: 1 April 2010 Edited by: Angioletta Coradini and Diego Turrini EJSM Origins White Document EJSM Origins White Document A. Coradini, D. Gautier, T. Guillot, B. Moore, G. Schubert, D. Turrini and H. Waite In the ESA Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 program the investigation of the conditions for planetary formation and that of the evolution of the Solar System were among the leading themes. These two themes, in fact, are strictly interlinked, since a clear vision of the origins of the Solar System cannot be achieved if we cannot discern those features which are due to the secular evolution from those which are primordial legacies of the formation time. In the context of the EJSM/Laplace proposal for a mission to Jupiter and the Jovian system, the Origins working group tried to identify the measurements to be performed in the Jovian system that could hold clues to unveil the formation histories of Jupiter and the Solar System. As we anticipated, part of the aspects to be investigated is entwined with the study of the evolution of the Solar and Jovian systems. The identified measures and their scientific domains can be divided into three categories, which will be described in the next sessions. Jupiter and the origins of giant planets As concerns the origin of Jupiter, the main interest of the EJSM mission lies in the investigation of Jupiter's composition and internal structure.