JBA Consulting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISFC Annual Report 1999

1999 Salmon, Sea Trout . 3 Location Map for Awards Presentation in Doyle Burlington Brown Trout (Lake) . 4 Brown Trout (River) . 5 Bream . 6 Pike (Lake), Pike (River) . 8 Carp . 10 Eel, Roach/Bream Hybrid . 11 Rudd/Bream Hybrid, Perch . .12 Tench . 13 Bass . 14 Coalfish, Cod, Conger Eel, Dab, Greater Spotted Dogfish . 15 Lesser Spotted Dogfish, Spur Dogfish . 16 Flounder, Garfish, Grey Gurnard . 17 Red Gurnard, Tub Gurnard, Ling . 18 Mackerel . 19 Grey Mullet, Plaice . 20 ONTENTS Pollack, Pouting . 21 Blonde Ray, Homelyn Ray, Painted Ray . 22 Sting Ray, Three Bearded Rockling, Twaite Shad . 24 C Blue Shark . 25 Tope, Torsk, Ballan Wrasse, Cuckoo Wrasse . 26 New Records, Ten Species Award, Ten Pin Awards, Special Award for Juveniles, The Minister’s Award, . .27 Revised Specimen Weight/New Class, Special Notice, Limitation on Number of Claims, Exclusion from Specimen Status, Weighing of Fish, Metrification . 28 Common Skate, Captors Addresses, Distribution of Specimen Awards . .29 Acknowledgements, Presentation of Awards 1998, Fund Raising . 30 Accounts, Donations . 31 Use of the information contained in this report for press articles Balance Sheet . 32 and publicity is encouraged. It may be quoted without charge, Irish Record Fish Listing . 33 provided the source is acknowledged. Schedule of Specimen Weights (Revised) . 35 The report is copyright and prior permission to reproduce the Rules . 37 data for any other purpose other than reasonable review or Weighing Scale Certification – List of Centres . .40 analysis must be obtained in writing from the Irish Specimen Fish “Read it Carefully” by Des Brennan . 42 Committee. “Maybe we’ll stay at home this year!” by Derek Evans . -

Julianstown Road Upgrades, R132 Co. Meath North to South Townlands: Smithstown, Julianstown, Dimanistown East, Ballygarth, Whitecross

Julianstown Road Upgrades, R132 Co. Meath North to south townlands: Smithstown, Julianstown, Dimanistown East, Ballygarth, Whitecross Site Area: Upgrades over 2,100m of existing R132 road pavement plus tie-in works at four side junctions ITM: North: 712994, 771138 South: 714215, 769572 Record of Monuments and Places ME028-007: Wayside Cross (‘White Cross’) and ME028-067 Battlefield (general area for skirmish along R132 / Julianstown Bridge in 1641) Architectural Conservation Area Julianstown Architectural Conservation Record of Protected Structures Julianstown R132 Bridge RPS MH028-212 / NIAH 14323002 ITM 713403, 770371. Also proposed works on terrace of 6 houses RPS MH028-205, -206, -207, -209, -210, -211 (all NIAH 14323004) plus associated 7th house. Vicinity of Julianstown Barracks, MH028-202, Courthouse MH028-204, Old Mill Building MH028-208 Bungalow MH028-217 and Milestone LA RPS ID Draft No: 91563 Heritage Desk Based Review and Assessment Niall Roycroft, 19th February 2021 1 Non-Technical Summary Meath County Council is proposing to upgrade the R132 and the four associated junctions at Julianstown, (ITM 713403, 770371 centre) in Smithstown, Julianstown, Dimanistown East, Ballygarth, Whitecross townlands, County Meath. Road upgrades are over a distance of 2.1km and include improving road paving, footpaths-cycleways and kerbing realignment. The present R132 is the previous N1 Dublin-Belfast road via Drogheda and has been extensively widened and straightened in the later 20th C. Since the opening of the M1 in 2002, further traffic calming measures, footpaths and central reservations have been installed. There are four significant R132 straightening sections involving cut-off sections of the old road and the whole R132 has been widened over any previous roadside ditches and grass verges and almost all of the present roadside boundary is recent (apart from the cut-off sections). -

Julianstown Architectural Conservation Area Character Appraisal December 2009

Julianstown Architectural Conservation Area Character Appraisal December 2009 Julianstown Architectural Conservation Area Statement Of Character 1 Published by Meath County Council, County Hall, Navan, Co. Meath. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or otherwise, without either the prior written permission of the Publishers or a licence permitting restricted copying in Ireland issued by the Irish Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, The Irish Writers centre, 19 Parnell Square, Dublin 1. All photographs copyright of Meath County Council unless otherwise attributed. © Meath County Council 2009. Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Licence number 2009/31/CCMA Meath County Council. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. Historic maps and photographs are reproduced with kind permission of the Irish Architectural Archive and the Local Studies Section of Navan County Library. ISBN 978-1-900923-21-7 Design and typeset by Legato Design, Dublin 1 Julianstown Architectural Conservation Area Statement of Character Lotts Architecture and Urbanism On behalf of Meath County Council and County Meath Heritage Forum An action of the County Meath Heritage Plan 2007-2011 supported by Meath County Council and the Heritage Council Foreword In 2007 Meath County Council adopted the County Meath Heritage Plan 2007-2011, prepared by the County Heritage Forum, following extensive consultation with stakeholders and the public. The Heritage Forum is a partnership between local and central government, state agencies, heritage and community groups, NGOs local business and development, the farming sector, educational institutions and heritage professionals. -

Knockharley Landfill Ltd. Environmental Impact

KNOCKHARLEY LANDFILL LTD. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT (EIAR) FOR PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT AT KNOCKHARLEY LANDFILL VOLUME 1 - NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY NOVEMBER 2018 Knockharley Landfill Ltd. Kentstown, Navan,Co.Meath TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT ............................................................................................ 1 1.2 APPLICATION AND EIAR ............................................................................................. 2 1.3 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT ................................................................ 2 1.3.1 EIAR Methodology ............................................................................................ 2 1.3.2 EIAR Structure ................................................................................................ 3 1.4 DIFFICULTIES ENCOUNTERED ........................................................................................ 4 1.5 VIEWING AND PURCHASING THE EIAR ............................................................................. 4 2 DESCRIPTION OF EXISTING AND PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT .................................... 5 2.1 EXISTING DEVELOPMENT ............................................................................................. 5 2.1.1 Existing Road Networks .................................................................................... 5 2.1.2 Existing Buildings, Utilities, Fencing -

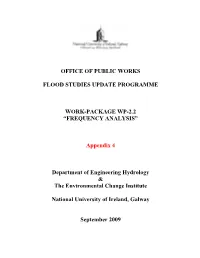

Frequency Analysis”

OFFICE OF PUBLIC WORKS FLOOD STUDIES UPDATE PROGRAMME WORK-PACKAGE WP-2.2 “FREQUENCY ANALYSIS” Appendix 4 Department of Engineering Hydrology & The Environmental Change Institute National University of Ireland, Galway September 2009 Appendix 4A1 6011 RIVER FANE @ MOYLES MILL Annual Maximum Floods 1957 to 2004.(no missing years) A1 A (km 2)= 234.00 N= 48 Year AMF(m 3 /s) Moments PWM L-Moments 1957 12.34 Mean 15.856 M100 15.856 L1 15.856 L-Cv 0.113 1958 21.07 Median 15.390 M110 8.825 L2 1.795 L-Skew 0.089 1959 15.39 Std.Dev. 3.195 M120 6.210 L3 0.161 L-Kur 0.074 1960 14.20 CV 0.202 M130 4.819 L4 0.134 1961 15.70 HazenS. 0.812 1962 13.39 30 1963 18.84 6011 RIVER FANE @ MOYLES MILL 1964 19.49 EV1 25 1965 18.14 1966 18.84 20 1967 13.39 winter peak 1968 15.39 15 1969 13.56 1970 10.94 AMF(m3/s) 10 1971 13.39 1972 10.90 1973 13.31 5 2 5 10 25 50 100 500 1974 14.37 1975 11.29 0 EV1 y 1976 19.13 -2-1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1977 11.68 30 1978 26.36 LO2 1979 16.91 25 1980 17.14 1981 17.04 20 1982 17.04 1983 19.35 15 1984 11.98 AMF(m3/s) 1985 12.49 10 1986 14.20 FANE CATCHMENT 1987 15.16 5 1988 15.45 2 5 10 25 50 100 500 1989 12.74 0 1990 14.88 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 1991 19.03 Logistic reduced variate 1992 12.87 1.5 1993 14.88 LogNormal 1994 16.89 1.4 1995 19.99 1996 15.16 1.3 1997 15.73 1998 14.88 1.2 1999 17.49 1.1 2000 19.51 log10(AMF) 2001 19.35 1 2002 19.67 2003 11.98 0.9 2004 18.10 2 5 10 25 50 100 500 0.8 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 Normal N(0,1) y COMMENTS 1. -

River Annalee Angling Map 8

9 River Annalee Angling Map 8 1 km 6 7 1km 4 5 1 3 2 11 10 CAVAN ANGLERS BUNNOE & DISTRICT ANGLERS Further upstream at Ashfield there is access to the river from the Cavan Anglers’ Club are the oldest club on the river. Founded in Bunnoe & District Anglers maintain a stretch of water that runs metal bridge. 1932, they maintain a section of water stretching from Ballyhaise upstream from Ballynallan Bridge as far as Porters Bridge. The Club Bunnoe River village upstream to Ballynallan Bridge. Some of the key angling also manages two tributaries, the Dromore and Bunnoe rivers. The Bunnoe River rises in Co. Monaghan and joins the Annalee stretches are described below: Annalee River upstream of Ballynallan Bridge. There is a good stock of wild brown Access 1 Ballyhaise – All the river area in and Access 4: It is possible to fish the river from trout and the river is best fished early in the season when water around Ballyhaise village is easily accessible and Ballynallan Bridge to where the Bunnoe River levels are high. there are parking facilities at Ballyhaise amenity joins the Annalee. This is considered to be one Access 7: Bunnoe Village behind the GAA pitch. centre right on the banks of the river. Good fishing of the best stretches on the river, especially is also to be had at the weir downstream from for the evening rise and it is possible to wade Access 8: Cappanagh Mills. Ballyhaise Bridge. The Weir is overlooked by a almost the entire run of water. beautiful old historic building which now serves as Access 9: On the Scotstown Road at Drumurchar. -

Out of Bent and Sand

out of bent and sand out of bent and sand Laytown & Bettystown Golf Club A centenary history: 1909–2009 brian keogh Printed in an edition of 1,000 Written by Brian Keogh Compiled by the Laytown & Bettystown centenary book committee: Eamon Cooney, Jack McGowan and Hugh Leech Edited by Rachel Pierce at Verba Editing House Design and typesetting by Áine Kierans Printed by Impress Printing Works © Brian Keogh and Laytown & Bettystown Golf Club 2009 www.landb.ie Brian Keogh is a freelance golf writer from Dublin. He is a regular contributor to The Irish Times, the Irish Sun, Irish Independent, RTÉ Radio, Setanta Ireland, Irish Examiner, Golf World, Sunday Tribune, Sunday Times and Irish Daily Star. A special acknowledgment goes to our sponsor, Thomas GF Ryan of Ryan International Corporation Contents foreword by Pádraig Harrington 8 chapter eight Welcome to the club 104 The importance of club golf Rolling out the red carpet to visitors for 100 years breaking 100 9 chapter nine Minerals and buns 116 A welcome from our centenary officers Junior golf at Laytown & Bettystown chapter one Once upon a time in the east… 12 chapter ten Flora & fauna by Michael Gunn 130 The founding of the club and its early development The plants and animals that make the links more than the sum of its parts chapter two Out of bent and sand 24 Emerging triumphant from a turbulent period of Irish history chapter eleven Love game: tennis whites and tees 134 The contribution of tennis to the club chapter three Professional pride 36 The club’s professionals chapter twelve -

Irish Fisheries Investiga Tions

IRISH FISHERIES INVESTIGA TIONS SERIES A (Freshwater) No. 13 (1973) AN ROINN TALMHAIOCHTA AGUS IASCAIGH (Department of Agriculture and Fisheries) FO-ROINN IASCAIGH (Fisheries Division) DUBLIN: PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE TO BE PURCHASED FROM THE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, G.P.O. ARCADE, DUBLIN. Price: 7!p IRISH FISHERIES INVESTIGATIONS SERIES A (FRESHWATER) No. 13 (1973) CHRISTOPHER MORIARTY STUDIES OF THE EEL Anguilla anguilla IN mELAND. 2. IN LOUGH CONN, LOUGH GILL AND NORTH CAVAN LAKES. -- Studies of the eel Anguilla anguilla in Ireland. 2. In Lough Conn, Lough Gill and North Cavan Lakes. by CHRISTOPHER MORIARTY Departmerrt of Agriculture and Fisheries, Dublin. (Received February 1, 1973}. ABSTRACT A total of 843 immature eels of length 27 to 86 em and ages 5 to 28 years were collected in summer by fyke netting, The North Cavan eels formed a distinct population of large, fast-growing eels, most of which matured before 12 years. The eels of the other lakes were slower in growth and in maturing, substantial numbers of 13 years and older being found. Principal food organisms in-' the Cavan ee'ls were fish and chironomid larvae; in Lough Gill fish for eels of over 50 em and Gammarus and Ephemeroptera larvae for smaller; in Lough Conn, Gastropoda for all sizes. 1. INTRODUCTION The first paper in this series (Moriarty 1973} described the standard techniques used in studying the populations of resident, immature or "yellow" eels in Irish waters. The present paper gives the results of sampling in eight lakes and one portion of river in the northern part of the' country, Loughs Gill and Conn lie on separate river systems while the North Cavan lakes investigated all lie on the River Erne or its trihn taries. -

County Meath Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020 Are Set out Below

County Meath Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020 Meath County Council Acknowledgements Thanks to John Wann and Aulino Wann and Associates for undertaking the biodiversity audit and research to inform this plan. Thanks to Dr. Carmel Brennan (Project Officer Meath and Monaghan) and Abby McSherry (Action for Biodiversity Project Officer) for managing the process of the Biodiversity Audit. Data and information was kindly provided by Tadhg Ó Corcora (Irish Peatland Conservation Council), National Biodiversity Data Centre, Meath branch of Birdwatch Ireland, Dr. Joanne Denyer (Denyer Ecology), Maria Long (BSBI Irish Officer), Dr Maurice Eakin (District Conservation Officer, National Parks and Wildlife Service), Bumblebee Conservation Trust, Balrath Woods Preservation Group, Sonairte National Ecology Centre, Margaret Norton (BSBI Co Meath recorder), Tidy Towns Groups, Columbans Dalgan Park, Navan, Jochen Roller (National Parks & Wildlife Service), Bat Conservation Ireland, Irish Wildlife Trust, Inland Fisheries Ireland, Paul Whelan (Lichens Ireland), Coillte Teoranta, Una Fitzpatrick (Biodiversity Ireland), Woods of Ireland, Irish Natural Forestry Foundation, Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, Meath/Cavan Bat Group, Boyne branch of the Inland Waterways Association of Ireland, Kate Flood (Meath Eco Tours), Controlling Priority Invasive Non-Invasive Riparian Plants and Restoring Native Biodiversity CIRB project. Action for Biodiversity Project was part financed by the European Union’s European Regional Development Fund through the INTERREG IVA Cross Border Programme managed by the Special EU Programmes Body. Meath County Council would like to thank the County Meath Heritage Forum, in particular the Natural Heritage and Biodiversity Working Group, for their work, co-operation and commitment in preparing this Biodiversity Action Plan. The Forum would like to extend their gratitude to Megan Tierney for administrative assistance. -

List of Rivers of Ireland

Sl. No River Name Length Comments 1 Abbert River 25.25 miles (40.64 km) 2 Aghinrawn Fermanagh 3 Agivey 20.5 miles (33.0 km) Londonderry 4 Aherlow River 27 miles (43 km) Tipperary 5 River Aille 18.5 miles (29.8 km) 6 Allaghaun River 13.75 miles (22.13 km) Limerick 7 River Allow 22.75 miles (36.61 km) Cork 8 Allow, 22.75 miles (36.61 km) County Cork (Blackwater) 9 Altalacky (Londonderry) 10 Annacloy (Down) 11 Annascaul (Kerry) 12 River Annalee 41.75 miles (67.19 km) 13 River Anner 23.5 miles (37.8 km) Tipperary 14 River Ara 18.25 miles (29.37 km) Tipperary 15 Argideen River 17.75 miles (28.57 km) Cork 16 Arigna River 14 miles (23 km) 17 Arney (Fermanagh) 18 Athboy River 22.5 miles (36.2 km) Meath 19 Aughavaud River, County Carlow 20 Aughrim River 5.75 miles (9.25 km) Wicklow 21 River Avoca (Ovoca) 9.5 miles (15.3 km) Wicklow 22 River Avonbeg 16.5 miles (26.6 km) Wicklow 23 River Avonmore 22.75 miles (36.61 km) Wicklow 24 Awbeg (Munster Blackwater) 31.75 miles (51.10 km) 25 Baelanabrack River 11 miles (18 km) 26 Baleally Stream, County Dublin 27 River Ballinamallard 16 miles (26 km) 28 Ballinascorney Stream, County Dublin 29 Ballinderry River 29 miles (47 km) 30 Ballinglen River, County Mayo 31 Ballintotty River, County Tipperary 32 Ballintra River 14 miles (23 km) 33 Ballisodare River 5.5 miles (8.9 km) 34 Ballyboughal River, County Dublin 35 Ballycassidy 36 Ballyfinboy River 20.75 miles (33.39 km) 37 Ballymaice Stream, County Dublin 38 Ballymeeny River, County Sligo 39 Ballynahatty 40 Ballynahinch River 18.5 miles (29.8 km) 41 Ballyogan Stream, County Dublin 42 Balsaggart Stream, County Dublin 43 Bandon 45 miles (72 km) 44 River Bann (Wexford) 26 miles (42 km) Longest river in Northern Ireland. -

To County Meath & the Boyne Valley FREE Guide

meath 15.2b_Layout 1 11/02/2015 18:01 Page 1 FREE Guide 2015 Ireland’s Heritage Capital your complete holiday guide to County Meath & the Boyne Valley discoverboynevalley.ie meathtourism.ie meath 15.2b_Layout 1 11/02/2015 18:01 Page 2 meath 15.2b_Layout 1 11/02/2015 18:01 Page 3 Welcome to the Boyne Valley “The Boyne is not a showy river. It rises in Co Kildare and flows gently and majestically through County Meath and joins the sea at Drogheda in Co Louth some 112 kilometres later. It has none of the razzmatazz of its sister, the Shannon. It’s neither the longest river in Ireland, nor does it have the greatest flow. What is does have, and by the gallon, is history. In fact, the Boyne Valley is like a time capsule. Travel along it and you travel through millennia of Irish history, from passage tombs that pre-date the Pyramids, to the Hill of Tara, seat of the High Kings of Ireland, all the way to the home of the First World War poet Francis Ledwidge in Slane. It’s the Irish equivalent of Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. And you can choose to explore it by car, bicycle, kayak, or by strolling along its banks and the towpaths of the navigation canals that run alongside from Navan to Oldbridge.” Frances Power - Editor, Cara, the Aer Lingus inflight magazine - Boyne Valley Feature, October/November 2014 Pg 68-78 Cara magazine is available online at issuu.com Contents Towns & Villages 3 Boyne Valley Drive 8 Heritage Trail 9 Golf 11 Biking & Walking 13 Horse Racing 15 Gardens 17 Travelling to Meath & Map 19 Crafts 21 Angling 23 Things to Do 25 Shopping 28 Festivals & Events 29 Accommodation 33 Food & Drink 37 1 2 Image credits: Front cover image by Stephen Keaveny - winner of the 2014 Wiki Loves Monuments national photography competition. -

Appropriate Assessment Screening Report

Abhantrach 08 River Basin Appropriate Assessment Screening Report Nanny – Delvin 2018 Appropriate Assessment Screening Report For River Basin (08) Nanny – Delvin Flood Risk Management Plan Areas for Further Assessment included in the Plan: Domhnach Bat Donabate Port Reachrann Portrane Cill Dhéagláin Ashbourne Baile Brigín Balbriggan Baile an Bhiataigh Bettystown Baile Mhic Gormáin Gormanston Damhliag Duleek Na Sceirí Skerries Lusca Lusk Baile Stafaird / Tuirbhe Staffordstown / Turvey An Seanbhaile Oldtown Ráth Tó Ratoath Sord Swords An Ros Rush Flood Risk Management Plans prepared by the Office of Public Works 2018 In accordance with European Communities (Assessment and Management of Flood Risks) Regulations 2010 and 2015 Purpose of this Report As part of the National Catchment-based Flood Risk Assessment & Management (CFRAM) programme, the Commissioners of Public Works have commissioned expert consultants to prepare Strategic Environmental Assessments, Appropriate Assessment Screening Reports and, where deemed necessary by the Commissioners of Public Works, Natura Impacts Assessments, associated with the national suite of Flood Risk Management Plans. This is necessary to meet the requirements of both S.I. No. 435 of 2004 European Communities (Environmental Assessment of Certain Plans and Programmes) Regulations 2004 (as amended by S.I. No. 200/2011), and S.I. No. 477/2011 European Communities (Birds and Natural Habitats) Regulations 2011. Expert Consultants have prepared these Reports on behalf of the Commissioners of Public Works to inform the Commissioners' determination as to whether the Plans are likely to have significant effects on the environment and whether an Appropriate Assessment of a plan or project is required and, if required, whether or not the plans shall adversely affect the integrity of any European site.