Voorbereid Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Onderzoek Ervaren Drugsoverlast in Maastricht 0- & 1-Meting

Onderzoek Ervaren drugsoverlast in Maastricht 0- & 1-meting In opdracht van Gemeente Maastricht september 2014 © Flycatcher Internet Research, 2004 Dit materiaal is auteursrechtelijk beschermd en kopiëren zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever is dan ook niet toegestaan. Inhoudsopgave 1. Inleiding pag. 1 1.1 De vragenlijst pag. 1 1.2 Onderzoeksmethode en steekproef pag. 1 1.3 Respons pag. 2 1.4 Betrouwbaarheid en generaliseerbaarheid pag. 2 1.5 Weging pag. 3 2. Resultaten 0- & 1-meting pag. 4 2.1 De eigen wijk pag. 4 2.2 Overlast in andere delen van de gemeente pag. 17 2.3 Het doen van een melding pag. 20 3. Uitsplitsingen pag. 26 3.1 Achtergrondkenmerken pag. 27 3.2 Aanvullende achtergrondvragen pag. 29 3.3 Stadsdeel 0-meting pag. 32 3.4 Stadsdeel 1-meting pag. 47 3.5 Vergelijking in de tijd pag. 62 4. Samenvatting pag. 66 4.1 De eigen wijk pag. 66 4.2 Overlast in andere delen van de gemeente pag. 67 4.3 Het doen van een melding pag. 67 Bijlagen pag. 68 1. Inleiding In Maastricht is op 1 mei 2012 gestart met het project Frontière om drugsoverlast en drugscriminaliteit in de gemeente aan te pakken. Het project volgde op landelijke wijzigingen in het softdrugsbeleid en het spreidingsbeleid dat de gemeente vóór 1 mei 2012 ontwikkelde. Sinds de veranderingen in het softdrugsbeleid en de start van het project Frontière is het softdrugsverkeer op straat (met name van buitenlandse bezoekers) afgenomen, de ervaren overlast lijkt te zijn afgenomen en de illegale softdrugsmarkt is gekrompen. Echter, uit verschillende hoeken werd door inwoners geklaagd over overlast als gevolg van drugs en dealers. -

En De Joodse Vluchtelingen in Amby

Burgemeester Hermens (1877-1965) en de Joodse vluchtelingen in Amby Peter Jan Knegtmans* Het verhaal wil dat op een ochtend in het voorjaar van 1933 een groep van een veertigtal uit Duitsland afkomstige Joodse vluchtelingen, veelal jonge gezinnen met koffers en kinderwagens, in het Zuid-Limburgse dorp Amby voor Huize Severen stond. De snel gewaarschuwde veldwachter bracht de hele groep naar het vlakbij gelegen huis van de burgemeester. De burgemeester en de veldwachter gaven hen te eten en regelden vervolgens huisvesting in een tiental leegstaande huizen aan wat toen de Hoofdstraat heette.1 Dit verhaal is te mooi om niet waar te zijn. Toch roept het vragen op. Want wat bracht deze groep naar Amby? Amby is nu een wijk in de noordoostelijke hoek van Maastricht, maar was toen een zelfstandige gemeente. Huize Severen was een opvanghuis van de Zusters van Barmhartigheid voor meisjes en vrouwen. In het dorp bestond geen Joodse gemeente waarmee de vluchtelingen contact hadden en die voorlopig ondersteuning kon of leek te kunnen bieden. Er woonden op dat moment zelfs helemaal geen Joden. Ook is er niets waaruit blijkt dat het dorp of zijn bestuur de reputatie hadden open te staan voor de opvang van vluchtelingen of zelfs maar bekendheid genoten in Duitsland. Er was geen industrie die werkgelegenheid bood en op het eerste gezicht was er weinig of niets dat het dorp interessant maakte als toevluchtsoord. Toch bleef het niet bij het genoemde veertigtal of hoeveel het er in feite geweest kunnen zijn. Het is daarom interessant na te gaan wat de aanleiding kan zijn geweest voor het relatief grote aantal Joodse vluchtelingen dat zich in Amby vestigde, hoe het hen verging en wat hierbij de rol was van het gemeentebestuur, in het bijzonder die van zijn burgemeester, Martin Hermens. -

1E&B.VP:Corelventura

Environment and Behavior http://eab.sagepub.com Modeling Consumer Perception of Public Space in Shopping Centers Harmen Oppewal and Harry Timmermans Environment and Behavior 1999; 31; 45 DOI: 10.1177/00139169921971994 The online version of this article can be found at: http://eab.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/31/1/45 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Environmental Design Research Association Additional services and information for Environment and Behavior can be found at: Email Alerts: http://eab.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://eab.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Downloaded from http://eab.sagepub.com at Eindhoven Univ of Technology on October 26, 2007 © 1999 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. ENVIRONMENTOppewal, Timmermans AND BEHAVIOR / CONSUMER / January PERCEPTION 1999 OF PUBLIC SPACE MODELING CONSUMER PERCEPTION OF PUBLIC SPACE IN SHOPPING CENTERS HARMEN OPPEWAL is assistant professor in the Department of Urban Planning of the Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands, and senior lecturer at the Department of Marketing of the University of Sydney, Australia. His research interest focuses on modeling human decision making in retailing, urban planning, and trans- portation. HARRY TIMMERMANS is chaired professor of urban planning at the Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands. His research interests include modeling consumer preference and choice behavior, and decision support systems in a variety of application contexts. ABSTRACT: This article presents a study of the effects of various shopping center design and management attributes on consumer evaluations of the public space ap- pearance (or atmosphere) in shopping centers. -

Official Journal of the European Communities L 39/29

14.2.2000 EN Official Journal of the European Communities L 39/29 COMMISSION DECISION of 22 December 1999 listing the areas of the Netherlands eligible under Objective 2 of the Structural Funds for the period 2000 to 2006 (notified under document number C(1999) 4918) (Only the Dutch text is authentic) (2000/118/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, eligible under Objective 2 with due regard to national priorities, without prejudice to the transitional support Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European provided for in Article 6(2) of that Regulation; Community, (5) Article 4(11) of Regulation (EC) No 1260/1999 provides Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 1260/1999 of that each list of areas eligible under Objective 2 is to be 21 June 1999 laying down general provisions on the valid for seven years from 1 January 2000; however, Structural Funds (1), and in particular the first subparagraph of where there is a serious crisis in a given region, the Article 4(4) thereof, Commission, acting on a proposal from a Member State, may amend the list of areas during 2003 in accordance After consulting the Advisory Committee on the Development with paragraphs 1 to 10 of Article 4, without increasing and Conversion of Regions, the Committee on Agricultural the proportion of the population within each region Structures and Rural Development and the Management referred to in Article 13(2) of that Regulation, Committee for Fisheries and Aquaculture, Whereas: HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION: (1) point 2 of the first subparagraph of Article 1 of Regulation (EC) No 1260/1999 provides that Objective 2 Article 1 of the Structural Funds is to support the economic and social conversion of areas facing structural difficulties; The areas in the Netherlands eligible under Objective 2 of the Structural Funds for the period 2000 to 2006 are listed in the (2) the first subparagraph of Article 4(2) of Regulation (EC) Annex hereto. -

Analyse En Aanbevelingen Heer En Scharn

Vlak vervangen door foto Analyse en aanbevelingen Heer en Scharn Juni 2011 Colofon Gemeente Maastricht; . Maastricht, 28 juni 2011 Copyright: Gemeente Maastricht Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestem- ming van de gemeente Maastricht. pagina 2 Analyse en aanbevelingen Heer en Scharn Juni 2011 pagina pagina Inhoudsopgave Analyse en aanbevelingen Heer 39 Heer en Scharn 3 Hoofdstuk 6 Overzicht studies en projecten 41 Ten noorden van de Akersteenweg 41 Inleiding 7 Ten zuiden van de Akersteenweg 4 Deel 1 Analyse 9 Deel 2 Aanbevelingen 45 Hoofdstuk 1 Cultuurhistorie 11 Hoofdstuk 7 Raamwerk groen, verkeer en openbare Historische ontwikkeling 11 ruimtes 47 Waardering ensembles 1 Relatie met het Heuvelland 47 Hoofdstuk 2 Groen en landschap 19 Relatie met de binnenstad 47 Assenkruis Akersteenweg - 49 Groen op stadsdeelsniveau 19 Dorpsstraat 49 Groen op wijkniveau 21 De Akersteenweg 51 Groen op buurtniveau 2 De Dorpsstraat 5 Water 2 Kruispunt Akersteenweg - Dorpsstraat 5 Hoofdstuk Verkeer 27 Groenstructuur op wijkniveau 5 Huidige verkeersstructuur Heer/ Hoofdstuk 8 Woonvisie 9 Scharn 27 Infrastructurele maatregelen op Saldo 0 9 korte termijn 29 Infrastructuur in relatie tot 31 ruimtelijke ontwikkelingen 31 Hoofdstuk Voorzieningen 3 Sport 3 Onderwijs en maatschappelijke 3 voorzieningen 3 Detailhandel 3 Hoofdstuk Wonen 37 Scharn 37 pagina pagina 6 Inleiding Dit rapport is opgebouwd uit 2 delen, een analysedeel en een deel.met station Randwyck, wordt voorlopig vrijgehouden en blijft een reserve- aanbevelingen locatie voor de toekomst. In deel 1, de Analyse, komen achtereenvolgens de onderwerpen cultu- Aan de zuidzijde hiervan kunnen de locatie van de Burght en omge- urhistorie, groen en landschap, verkeer, voorzieningen en wonen aan ving mogelijk ontwilkkeld worden. -

CRO Maastricht Aachen Airport

Nieuwsbrief Stop groei MAA September 2020 #3 Pagina 1 van 6 Deze nieuwsbrief, een uitgave van Alliantie Tegen Uitbreiding MAA, verschijnt wanneer hier aanleiding toe is. De Alliantie is altijd bereid om met politici van alle partijen in gesprek te gaan over MAA. Neem hiertoe contact op d.m.v. onderstaand e-mailadres. [email protected] www.stopgroeimaa.nl www.facebook.com/vlieghinderZuidLimburg CRO Maastricht Aachen Airport De Commissie Regionaal Overleg luchthaven MAA is door de minister ingesteld en moet d.m.v. overleg tussen de betrokkenen zorgen voor De OmwonendenMAA zijn niet een balans tussen de economische belangen van het vliegveld en de vertegenwoordigd in de CRO belangen van de omgeving. De OmwonendenMAA, de belangenvereniging van omwonenden, is echter helemaal niet vertegenwoordigd in de CRO. Hoe dat kan? Doordat men spelregels hanteert die voor de andere CRO-leden niet gelden. Normaal gesproken-vraagt de CRO aan een organisatie of ze iemand willen afvaardigen. Maar t.a.v. de omwonenden heeft men bedacht dat er op persoonlijke titel en zonder last of ruggespraak benoemd kan worden door de voorzitter Hub Meijers. Ook moet een sollicitant “betrokkenheid bij luchtvaart” hebben. Dat verklaart waarom er 2 ex- verkeersleiders op de stoelen van omwonenden zitten. Woonplaatsen van deze leden-omwonenden zijn o.a. Eijsden-Margraten en Amby. Dat zijn niet direct de locaties waar men meemaakt wat wij dagelijks ervaren. Wij willen mensen uit Schietecoven, Moorveld of Geverik als CRO-leden- omwonenden. Omgevingsconvenant Dit gegeven staat niet op zich. In februari 2019 is in de CRO het omgevingsconvenant aangenomen. De naam suggereert dat OmwonendenMAA als burgerinitiatief met 450 leden hier onderdeel van uitmaakt. -

Meerjaren Prognose

Meerjaren Prognose Grond- en Vastgoedexploitaties 2017 Versie gemeenteraad juni 2018 Colofon De Meerjaren Prognose Grond- en Vastgoedexploitaties 2017 is een productie van de teams Vastgoed en Projectmanagement Voor meer informatie: Monique Konings | Plan- en Vastgoedeconoom Vastgoed Beleid en Ontwikkeling | Gemeente Maastricht T (043) 350 46 30 | E [email protected] Mosae Forum 10, 6211 DW Maastricht | Postbus 1992, 6201 BZ Maastricht | www.gemeentemaastricht.nl Meerjarenprognose Grond- en Vastgoedexploitaties 2017 – versie gemeenteraad juni 2018 2 INHOUDSOPGAVE Inhoudsopgave ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Managementsamenvatting ................................................................................................................... 7 1. Inleiding .................................................................................................................................... 12 1.1 Doelstelling MPGV ...................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Aanpak MPGV ............................................................................................................................. 13 1.3 Leeswijzer ................................................................................................................................... 15 2. Uitgangspunten en parameters ............................................................................................. -

Maastricht: a True Star Among Cities

city guide : city 2 : culture 24 : shopping 48 : culinary & out on the town 60 : active in South Limburg 84 : practical information 95 2/3 : city Maastricht: a true star among cities Welcome to Maastricht, one of the oldest cities in the Netherlands – a city that has ripened well with age, like good wine, with complex and lively cultural overtones added over centuries by the Romans, germans and French. this rich cultural palette is the secret behind the city’s attractive- Welcome ness, drawing visitors to the historic city centre If you pass by the most famous and a wealth of museums and festivals – making square in Maastricht, you will each visit a fascinating new experience. undoubtedly notice the fantas- tic and colourful set of figures But Maastricht is also a vibrant makes Maastricht special – in representing the Carnival and contemporary city with a the heart of the South Limburg orchestra ‘Zaate Herremenie.’ rich landscape of upmarket as hill country and nestled in the The Carnival celebration, or well as funky boutiques and a Meuse River Valley. Is it any ‘Vastelaovend’ as it is called wide range of restaurants & wonder that Maastricht is such by the locals, lasts only three cafés serving everything from a great place for a day out, a days, but this trumpet player local dishes, hearty pub food, weekend getaway, or a longer welcomes visitors to the and great selections of beer holiday? Vrijthof all year round. to the very best haute cuisine. Maastricht: a true star And of course its location also among cities. : city / welcome : city / zicht op Maastricht 4/5 compact and pedestrianfriendly A true son discover The centre of Maastricht is compact and easy to explore on of Maastricht Maastricht on foot. -

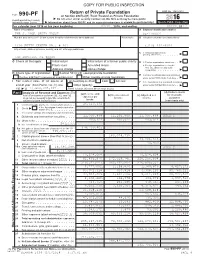

Attach to Your Tax Return. Department of the Treasury Attachment Sequence No

&23<)2538%/,&,163(&7,21 Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2016 or tax year beginning07/01 , 2016, and ending 06/30 , 20 17 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST 95-1790021 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 1200 GETTY CENTER DR., # 401 (310) 440-6040 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here LOS ANGELES, CA 90049 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the Address change Name change 85% test, check here and attach computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here X I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part II, col. -

Platform Abstracts

American Society of Human Genetics 65th Annual Meeting October 6–10, 2015 Baltimore, MD PLATFORM ABSTRACTS Wednesday, October 7, 9:50-10:30am Abstract #’s Friday, October 9, 2:15-4:15 pm: Concurrent Platform Session D: 4. Featured Plenary Abstract Session I Hall F #1-#2 46. Hen’s Teeth? Rare Variants and Common Disease Ballroom I #195-#202 Wednesday, October 7, 2:30-4:30pm Concurrent Platform Session A: 47. The Zen of Gene and Variant 15. Update on Breast and Prostate Assessment Ballroom III #203-#210 Cancer Genetics Ballroom I #3-#10 48. New Genes and Mechanisms in 16. Switching on to Regulatory Variation Ballroom III #11-#18 Developmental Disorders and 17. Shedding Light into the Dark: From Intellectual Disabilities Room 307 #211-#218 Lung Disease to Autoimmune Disease Room 307 #19-#26 49. Statistical Genetics: Networks, 18. Addressing the Difficult Regions of Pathways, and Expression Room 309 #219-#226 the Genome Room 309 #27-#34 50. Going Platinum: Building a Better 19. Statistical Genetics: Complex Genome Room 316 #227-#234 Phenotypes, Complex Solutions Room 316 #35-#42 51. Cancer Genetic Mechanisms Room 318/321 #235-#242 20. Think Globally, Act Locally: Copy 52. Target Practice: Therapy for Genetic Hilton Hotel Number Variation Room 318/321 #43-#50 Diseases Ballroom 1 #243-#250 21. Recent Advances in the Genetic Basis 53. The Real World: Translating Hilton Hotel of Neuromuscular and Other Hilton Hotel Sequencing into the Clinic Ballroom 4 #251-#258 Neurodegenerative Phenotypes Ballroom 1 #51-#58 22. Neuropsychiatric Diseases of Hilton Hotel Friday, October 9, 4:30-6:30pm Concurrent Platform Session E: Childhood Ballroom 4 #59-#66 54. -

“Het Voelt Als VAKANTIE Om Hier Te Wonen” 1 | 17

1 | 17 Buurten is een uitgave van Woningstichting Maasvallei Maastricht voor huurders en relaties Stagiares van Maasvallei Huurdersvereniging De groene vingers van Maasvallei Zomerpagina 03 Maasvallei is een erkend leerbedrijf 06 Riny Jalhay: 06 Maasvallei heeft in 2016 twee bedrijven 08 en begeleidt met grote regelmaat “Het belang van geselecteerd voor groenonderhoud bij Recepten en handige tips om stagiares van diverse opleidingen. onze huurders de complexen. Vaessen Groenvoorzie- volop te genieten van een ning en Rooden Landscape Solutions. staat altijd heerlijke zomer. voorop” Albert en Jeanne Schiepers verhuisden naar een koopwoning in Trichterveld: De ondergrondse oplossing voor de wateroverlast in “Het voelt als VAKANTIE Heer om hier te wonen” Trichterveld krijgt steeds meer vorm. De vernieuwing geeft de wijk een mooie uitstraling. Witte gladde muren, rode daken en De afgelopen jaren kwam Heer meerdere grijze kozijnen, de nieuwe wonin- keren in het nieuws vanwege wateroverlast. gen hebben zelfs iets sjieks. En Bij iedere hoosbui hielden de inwoners van toch, als je door de wijk loopt, is Heer hun adem in. Vooral in de omgeving van het Plein Sint Petrus Banden ondervon- de sfeer onaangetast. De smalle den de bewoners veel overlast van het water. straten, het vele groen en het type Met de aanleg van de twee waterbuffers lijkt huizen. Het blijft een intieme daar nu een eind aan te komen. gezellige wijk. Lees het complete interview met Dat is wat Albert (1952) en projectleider van de Gemeente Maas- Jeanne (1954) Schiepers aantrok. tricht Hans Thewissen op pagina 4. Het echtpaar verhuisde onlangs naar een koopwoning. De levensloopbestendige woning is casco was geen eis, wel een wens. -

Compulsive Purchasing As a Learned Adaptive Response

AN EXAMINATION OF THE NATURE OF A PROBLEMATIC/CONSUMER BEHAVIOR: COMPULSIVE PURCHASING AS A LEARNED ADAPTIVE RESPONSE ,j ADDICTION, AND PERSONALITY DISORDER DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Alicia L. Briney, B.S., M.B.A. Denton, Texas August 1989 Briney, Alicia L., An Examination of a Problematic Consumer Behavior; Compulsive Purchasing as a Learned Adaptive Response. Addiction, and Personality Disorder. Doctor of Philosophy (Marketing), August 1989, 188 pp., 22 tables, 12 figures, bibliography, 200 titles. The problem examined in this study was the nature of compulsive purchasing behavior. Three proposed models depicting this behavior as a learned adaptive response to anxiety and/or depression, an addiction, and a personality disorder were introduced and discussed in Chapter I. Background information concerning the areas examined in the models was presented in Chapter II. The research methodology was discussed in Chapter III and the findings of the research presented in Chapter IV. A summary, conclusions, implications, and recommendations were presented in Chapter V. The purpose of this research was to examine hypotheses in support of each of the three proposed models. Two separate quasi-experimental designs and three groups of subjects were used to test the hypotheses. The three groups used were compulsive purchasers, alcoholics, and overeaters. The first experiment utilized Scale 7 (Compulsive), Scale A (Anxiety), and Scale D (Dysthymia) on the MCMI-II to examine differences in personality patterns in the three groups. The second experiment utilized a self-report questionnaire to examine differences in compulsive purchasing behavior patterns in the three groups.