Thoughts About the Science Fiction (English Edition)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1: for Me, It Was Personal Names with Too Many of the Letter "Q"

1: For me, it was personal names with too many of the letter "q", "z", or "x". With apostrophes. Big indicator of "call a rabbit a smeerp"; and generally, a given name turns up on page 1... 2: Large scale conspiracies over large time scales that remain secret and don't fall apart. (This is not *explicitly* limited to SF, but appears more often in branded-cyberpunk than one would hope for a subgenre borne out of Bruce Sterling being politically realistic in a zine.) Pretty much *any* form of large-scale space travel. Low earth orbit, not so much; but, human beings in tin cans going to other planets within the solar system is an expensive multi-year endevour that is unlikely to be done on a more regular basis than people went back and forth between Europe and the americas prior to steam ships. Forget about interstellar travel. Any variation on the old chestnut of "robots/ais can't be emotional/creative". On the one hand, this is realistic because human beings have a tendency for othering other races with beliefs and assumptions that don't hold up to any kind of scrutiny (see, for instance, the relatively common belief in pre-1850 US that black people literally couldn't feel pain). On the other hand, we're nowhere near AGI right now and it's already obvious to everyone with even limited experience that AI can be creative (nothing is more creative than a PRNG) and emotional (since emotions are the least complex and most mechanical part of human experience and thus are easy to simulate). -

The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature

From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Dorian Townsend Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales May 2011 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Townsend First name: Dorian Other name/s: Aleksandra PhD, Russian Studies Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: School: Languages and Linguistics Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) The Slavic vampire myth traces back to pre-Orthodox folk belief, serving both as an explanation of death and as the physical embodiment of the tragedies exacted on the community. The symbol’s broad ability to personify tragic events created a versatile system of imagery that transcended its folkloric derivations into the realm of Russian literature, becoming a constant literary device from eighteenth century to post-Soviet fiction. The vampire’s literary usage arose during and after the reign of Catherine the Great and continued into each politically turbulent time that followed. The authors examined in this thesis, Afanasiev, Gogol, Bulgakov, and Lukyanenko, each depicted the issues and internal turmoil experienced in Russia during their respective times. By employing the common mythos of the vampire, the issues suggested within the literature are presented indirectly to the readers giving literary life to pressing societal dilemmas. The purpose of this thesis is to ascertain the vampire’s function within Russian literary societal criticism by first identifying the shifts in imagery in the selected Russian vampiric works, then examining how the shifts relate to the societal changes of the different time periods. -

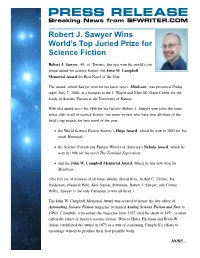

PRESS RELEASE Breaking News from SFWRITER.COM Robert J

PRESS RELEASE Breaking News from SFWRITER.COM Robert J. Sawyer Wins World’s Top Juried Prize for Science Fiction Robert J. Sawyer, 46, of Toronto, has just won the world’s top juried award for science fiction: the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Novel of the Year. The award, which Sawyer won for his latest novel, Mindscan, was presented Friday night, July 7, 2006, at a banquet at the J. Wayne and Elsie M. Gunn Center for the Study of Science Fiction at the University of Kansas. With this award win—his 38th for his fiction—Robert J. Sawyer now joins the most- select club in all of science fiction: the seven writers who have won all three of the field’s top awards for best novel of the year: • the World Science Fiction Society’s Hugo Award, which he won in 2003 for his novel Hominids; • the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America’s Nebula Award, which he won in 1996 for his novel The Terminal Experiment; • and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, which he has now won for Mindscan. (The full list of winners of all three awards: David Brin, Arthur C. Clarke, Joe Haldeman, Frederik Pohl, Kim Stanley Robinson, Robert J. Sawyer, and Connie Willis; Sawyer is the only Canadian to win all three.) The John W. Campbell Memorial Award was created to honor the late editor of Astounding Science Fiction magazine (renamed Analog Science Fiction and Fact in 1960). Campbell, who edited the magazine from 1937 until his death in 1971, is often called the father of modern science fiction. -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

The Drink Tank - the Hugo for Best Novel 2013 the Drink Tank 347 - the Hugo for Best Novel 2013

The Drink Tank - The Hugo for Best Novel 2013 The Drink Tank 347 - The Hugo for Best Novel 2013 Contents Cover by Bryan Little! “Hugo not bound by Space and Time” Page 2 - Table of Contents / Art Credits / This Stuff Captain Vorpatril’s Alliance “Contents” by Lois McMasters Bujold Page 3 On The Shortlist Page 19 - A Very Loosely Related Article by Steve Diamond (of Elitist Book Reviews) By Christopher J Garcia Art from Kurt Erichsen “Yeah, I’ve got nothing.” “I’ve read a lot of books...” Page 20 - A Review by Sara Dickinson “Insofar as suspense goes...” The Throne of the Crescent Moon Page 22 - 2 Reviews - by Saladin Ahmed By Liz Lichtfield Page 5 - A Very Loosely Related Article “This was entirely too funny for words.” by Christopher J Garcia By Kate “...some are hugely important symbols, while “Oh, this was funny...” others are just over-hyped chairs.” Page 6 - A Review by Juan Sanmiguel 2312 “It will be interesting to see were Ahmed will by Kim Stanley Robinson take us next.” Page 23 - A Very Loosely Related Article Page 7 - A Review by Mihir Wanchoo By Christopher J Garcia “The book’s size is definitely on the thinner “In 300 years, I will be 338.” side and this might be going against the norm...” Page 24 - A Review by Anne Charnock Page 10 - A Review by Nadine G. “...Robinson has written a humungous book...” “...just putting things in the desert doesn’t make Page 25 - A Review by Maria Tomchick a great book either.” “...the author could use a good editor...” Page 26 - A Review of Beth Zuckerman Blackout “I recommend this book even though it’s about by Mira Grant terrorism...” Page 11 - A Very Loosely Related Article By Christopher J Garcia Redshirts “...and over the radio system came a name - by John Scalzi Sunil Tripathi. -

The Drink Tank 252 the Hugo Award for Best Novel

The Drink Tank 252 The Hugo Award for Best Novel [email protected] Rob Shields (http://robshields.deviantart.com/ This is an issue that James thought of us doing Contents and I have to say that I thought it was a great idea large- Page 2 - Best Novel Winners: The Good, The ly because I had such a good time with the Clarkes is- Bad & The Ugly by Chris Garcia sue. The Hugo for Best Novel is what I’ve always called Page 5 - A Quick Look Back by James Bacon The Main Event. It’s the one that people care about, Page 8 - The Forgotten: 2010 by Chris Garcia though I always tend to look at Best Fanzine as the one Page - 10 Lists and Lists for 2009 by James Bacon I always hold closest to my heart. The Best Novel nomi- Page 13 - Joe Major Ranks the Shortlist nees tend to be where the biggest arguments happen, Page 14 - The 2010 Best Novel Shortlist by James Bacon possibly because Novels are the ones that require the biggest donation of your time to experience. There’s This Year’s Nominees Considered nothing worse than spending hours and hours reading a novel and then have it turn out to be pure crap. The Wake by Robert J. Sawyer flip-side is pretty awesome, when by just giving a bit of Page 16 - Blogging the Hugos: Wake by Paul Kincaid your time, you get an amazing story that moves you Page 17 - reviewed by Russ Allbery and brings you such amazing enjoyment. -

SF Commentary 106

SF Commentary 106 May 2021 80 pages A Tribute to Yvonne Rousseau (1945–2021) Bruce Gillespie with help from Vida Weiss, Elaine Cochrane, and Dave Langford plus Yvonne’s own bibliography and the story of how she met everybody Perry Middlemiss The Hugo Awards of 1961 Andrew Darlington Early John Brunner Jennifer Bryce’s Ten best novels of 2020 Tony Thomas and Jennifer Bryce The Booker Awards of 2020 Plus letters and comments from 40 friends Elaine Cochrane: ‘Yvonne Rousseau, 1987’. SSFF CCOOMMMMEENNTTAARRYY 110066 May 2021 80 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 106, May 2021, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. .PDF FILE FROM EFANZINES.COM. For both print (portrait) and landscape (widescreen) editions, go to https://efanzines.com/SFC/index.html FRONT COVER: Elaine Cochrane: Photo of Yvonne Rousseau, at one of those picnics that Roger Weddall arranged in the Botanical Gardens, held in 1987 or thereabouts. BACK COVER: Jeanette Gillespie: ‘Back Window Bright Day’. PHOTOGRAPHS: Jenny Blackford (p. 3); Sally Yeoland (p. 4); John Foyster (p. 8); Helena Binns (pp. 8, 10); Jane Tisell (p. 9); Andrew Porter (p. 25); P. Clement via Wikipedia (p. 46); Leck Keller-Krawczyk (p. 51); Joy Window (p. 76); Daniel Farmer, ABC News (p. 79). ILLUSTRATION: Denny Marshall (p. 67). 3 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 34 TONY THOMAS TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 READING EXPERIENCE 3, 7 41 JENNIFER BRYCE A TRIBUTE TO YVONNNE THE 2020 BOOKER PRIZE -

April Fool's Issue 1950 West Broadway, Vancouver, BC, Tel

Inside Cover The newsletter of the B.C. Science Fiction Association BCSFAzine © April 2006, Volume 34, #4, Issue #395 is the monthly club newsletter published by the British Columbia Science Fiction Association, a social #395 $3.00 April 2006 organization. An e-mail membership (including email delivery of the newsletter in PDF or TXT format) is $15.00 per year; new memberships are $26.00 per year; membership renewals are $25.00 per year; a New Family membership (including 2 votes in WCSFA meetings) is $32.00. Please send membership renewals to the Treasurer at 7064 No. 1 Road, Richmond, BC V7C 1T6. These prices include subscription to BCSFAzine. Make cheques payable to WCSFA (West Coast Science Fiction Association). (NOTE: The West Coast Science Fiction Association is a separate, officially registered society.) For comments, subscriptions, suggestions, and/or submissions, write to: BCSFAzine, c/o Box 15335, VMPO, Vancouver, BC, CANADA V6B 5B1, or email [email protected] . BCSFA Executive President & Archivist: R. Graeme Cameron, 604-526-7522 Vice President (incumbent): Doug Finnerty, 604-526-5621 Treasurer: Kathleen Moore-Freeman, 604-277-0845 Slowly Graeme realized his editor was possessed Secretary: Barb Dryer, 604-263-0472 (Felicity Walker Photo) Editor: Garth Spencer, 604-325-7314 Keeper of FRED Book, VCon Ambassador for Life: Steve Forty, 604-936-4754 BCSFAzine is printed most excellently by the good people at Copies Plus, at April Fool's issue 1950 West Broadway, Vancouver, BC, tel. 604-731-7868. (Do you believe that?) BCSFAzine is distributed monthly at WHITE DWARF BOOKS, 3715 West 10th Avenue, Vancouver, BC, V6R 2G5, tel. -

Here Walking Fossil Robert A

The Anticipation Hugo Committee is pleased to provide a detailed list of nominees for the 2009 Science Fiction and Fantasy Achievement Awards (the Hugos), and the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer (Sponsored by Dell Magazines). Each category is delineated to five nominees, per the WSFS Constitution. Also provided are the number of ballots with nominations, the total number of nominations and the number of unique nominations in each category. Novel The Last Centurion John Ringo 8 Once Upon a Time Philip Pullman 10 Ballots 639; Nominations: 1990; Unique: 335 The Mirrored Heavens David Williams 8 in the North Slow Train to Arcturus Dave Freer 7 To Hie from Far Cilenia Karl Schroeder 9 Little Brother Cory Doctorow 129 Hunter’s Run Martin Dozois Abraham 7 Pinocchio Walter Jon Williams 9 Anathem Neal Stephenson 93 Inside Straight George R. R. Martin 7 Utere Nihill Non Extra John Scalzi 9 The Graveyard Book Neil Gaiman 82 The Ashes of Worlds Kevin J Anderson 7 Quiritationem Suis Saturn’s Children Charles Stross 74 Gentleman Takes Sarah A Hoyt 7 Harvest James Van Pelt 9 Zoe’s Tale John Scalzi 54 a Chance The Inferior Peadar O’Guilin 7 Cenotaxis Sean Williams 9 Matter Iain M. Banks 49 Staked J.F. Lewis 7 In the Forests of Jay Lake 8 Nation Terry Pratchett 46 Graceling Kristin Cashore 6 the Night An Autumn War Daniel Abraham 46 Small Favor Jim Butcher 6 Black Petals Michael Moorcock 8 Implied Spaces Walter Jon Williams 45 Emissaries From Adam-Troy Castro 6 Political Science by Walton (Bud) Simons 7 Pirate Sun Karl Schroeder 41 the Dead & Ian Tregillis Half a Crown Jo Walton 38 A World Too Near Kay Kenyon 6 Mystery Hill Alex Irvine 7 Valley of Day-Glo Nick Dichario 35 Slanted Jack Mark L. -

By Sergei Lukyanenko Шестой Дозор

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Шестой Дозор by Sergei Lukyanenko Шестой Дозор. Сергей Лукьяненко написал новый роман о полюбившемся миллионам мире Иных! «Шестой Дозор» – это логическое продолжение «Нового Дозора», в котором Ночному и Дневному Дозорам пришлось столкнуться с новым врагом – Сумраком. В мир Ночного и Дневного Дозоров, мир Гессера и Завулона, мир вечного противостояния Добра со Злом, мир магии, заклинаний, проклятий, вампиров, ведьм и волшебниц… Мир Великого Светлого мага Антона Городецкого. В Мир Сумрака, который вернулся в наш мир, чтобы разрушить его! На протяжении всей истории человечества Иные – Светлые и Темные – противостоят друг другу, сохраняя равновесие сил Света и Тьмы. Маги, ведьмы, оборотни, вампиры и другие Иные живут рядом с людьми, которые даже не подозревают об их существовании. © Сергей Лукьяненко, 2015 © Оформление. ООО «Издательство „АСТ“, 2015 © ООО «Аудиокнига», 2015. Предлагаем Вам скачать ознакомительный фрагмент книги «Шестой Дозор» автора Сергей Лукьяненко в электронном виде в форматах FB2 или TXT. Также можно скачать книгу в других форматах, таких как RTF и EPUB (электронные книги). Советуем выбирать для загрузки формат FB2 или TXT, которые в настоящее время поддерживаются практически каждым мобильным устроиством (в том числе телефонами / смартфонами / читалками электронных книг под управлением ОС Андроид и IOS (iPhone, iPad)) и настольными ПК. Книга вышла в 2014 году в серии «Дозоры». Библиография Сергея Лукьяненко - Sergei Lukyanenko bibliography. Сергей Лукьяненко. И др. (1990), Рыцари сорока островов. История о нескольких современных подростках, «скопированных» в искусственную среду, где они вынуждены играть в игру с очень жесткими правилами. Действие происходит на множестве небольших песчаных островков, которые соединены между собой узкими мостами, а весь мир находится под гигантским куполом, подобным куполу из «Шоу Трумэна». -

Download New Watch: Book Five (Night Watch) PDF

Download: New Watch: Book Five (Night Watch) PDF Free [122.Book] Download New Watch: Book Five (Night Watch) PDF By Sergei Lukyanenko New Watch: Book Five (Night Watch) you can download free book and read New Watch: Book Five (Night Watch) for free here. Do you want to search free download New Watch: Book Five (Night Watch) or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #New Watch: Book Five (Night Watch) | #331799 in Books | Sergei Lukyanenko | 2014-04-22 | 2014-04-22 | Original language: English | PDF # 1 | 8.00 x .62 x 5.31l, .0 | File type: PDF | 384 pages | New Watch Book Five Night Watch | |2 of 2 people found the following review helpful.| Worth Reading if You Liked the Other Books in the Series | By David Dubrow |It is far from a bad book. It's definitely worth your time, but only if you really liked the earlier volumes in the series. The main problem was that I felt New Watch was written just to continue the series, not tell a compelling story. Filtered through the lens of the supernatural, there are | From Booklist | Originally published in Russia in 2012, this is the fifth and concluding volume of the Night Watch series, in which two groups of supernatural beings, the Night Watch and the Day Watch, protect the b Full of treachery and intrigue, the fifth volume in Sergei Lukyananko’s internationally bestselling Night Watch series—a mesmerizing blend of noir and urban fantasy, set in contemporary Moscow, that tells the story of an ancient race of supernatural beings known as the Others. -

Post-Apocalypse, Intermediality and Social Distrust in Russian Pop Culture by Ulrich Schmid, St

RUSSIAN ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 126, 10 April 2013 2 ANALYSIS Post-Apocalypse, Intermediality and Social Distrust in Russian Pop Culture By Ulrich Schmid, St. Gallen Abstract Pop culture is not just entertainment. It conveys values, beliefs and even historic knowledge to a broad audi- ence. Often, pop culture even overrides institutionalized education and shapes ideological attitudes in the public sphere. In the Russian case, bestsellers, blockbuster movies and video games present peculiar narra- tives of societal or political orders that need to be taken into account when analyzing Russia’s potential for democratization. Metro 2033: A Multi-Media Success However, apart from the usual bleak conclusion, the In an age when the modern mass media is converging, it game also provides the possibility of a happy ending. If has become difficult to talk about isolated cultural events the player engages in good deeds like giving alms or in Russian pop culture. Frequently specific content sur- sparing enemies from death, he is able to eventually faces in one medium, but shortly afterwards undergoes arrange peace with the “Blacks.” This second solution several transformations and appears in another reincar- requires a high ethical commitment, otherwise the game nation as a movie, book or computer game.1 Such an falls back into the standard “Live and let die” mode. intermedial diversity buttresses the public presence of The basic weltanschauung (worldview) of the game is a certain style in a successful product. that of an eternal fight. The anthropological condition A good case in point is Dmitry Glukhovsky’s “Metro of the game “Metro 2033” implies a fragile individual 2033” science fiction project.