Videodisc Update '77

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

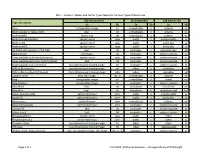

RDA -- Content, Media, and Carrier Type Values for Various Types Of

RDA -- Content, Media, and Carrier Type Values for Various Types of Resources 336 (rdacontent) 337 (rdamedia) 338 (rdacarrier) Type of resource $a $b $a $b $a $b Atlas cartographic image cri unmediated n volume nc Book (regular or large print) text txt unmediated n volume nc Book (braille) tactile text txt unmediated n volume nc Book on audiocassette spoken word spw audio s audiocassette ss Book on CD spoken word spw audio s audio disc sd Book on MP3 spoken word spw audio s audio disc sd CD-ROM with text (e.g., PDF files) text txt computer c computer disc cd Digital image still image sti computer c online resource cr Downloadable audio book (e-audio) spoken word spw computer c online resource cr Downloadable electronic book (e-book) text txt computer c online resource cr Downloadable video (e-video) two-dimensional moving image tdi computer c online resource cr DVD or Blu-ray disc two-dimensional moving image tdi video v videodisc vd DVD or Blu-ray disc (3-D movie) three-dimensional moving image tdm video v videodisc vd Graphic novel text, still image txt, sti unmediated n volume nc Map cartographic image cri unmediated n sheet nb Map (online) cartographic image cri computer c online resource cr Microfiche text txt microform h microfiche he Microfilm text txt microform h microform reel hd Music audiocassette performed music prm audio s audiocassette ss Music CD performed music prm audio s audio disc sd Music score notated music ntm unmediated n volume nc Music (streaming) performed music prm computer c online resource cr Online PDF text txt computer c online resource cr Online serial text txt computer c online resource cr Playaway (book) spoken word spw audio s other sz Playaway (music) performed music prm audio s other sz Playaway View two-dimensional moving image tdi video v other vz VHS tape two-dimensional moving image tdi video v videocassette vf Website (text, maps, photos) text, cartographic image, still image txt, cri, sti computer c online resource cr Page 1 of 1 4/13/2013 (Cathy Lamoureaux -- Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh). -

"Think It Through": an Interactive Videodisc for the Hearing Impaired

"THINK IT THROUGH": AN INTERACTIVE VIDEODISC FOR THE HEARING IMPAIRED Casey Garhart Stone and Gwen C. Nugent Media Development Project for the Hearing Impaired Lincoln, Neb. disc player with an external microcomputer. In this way the realistic, high quality visuals of the videodisc could join with the memory and branching capabili ties of the computer to provide the hearing impaired with an interactive and individualized visual com munication medium. The project used an MCA DiscoVision 7820 video disc player and a Radio Shack TRS-80 microcomput er to achieve this union of technologies. An IEEE port, a standard feature of the 7820 player, allows easy access for a two-way interface between the videodisc and the computer. Basically, the computer can be programmed to operate the player, and the player can indicate to the computer when it has exe Casey G. Stone Gwen C. Nugent cuted one command and is ready for the next. Unfortunately, this interface requires two moni tors because of the incompatibility of the two video The feasibility of interfacing a videodisc player signals. One monitor displays the videodisc picture, with an external microcomputer is discussed. while the other displays the computer graphics. For a young audience, and owing to the complex nature of From 1978 through 1980, the Media Development the proposed disc, it was determined that the double Project for the Hearing Impaired (MDPHI) at the monitor approach would be ill-advised, and there University of Nebraska worked under a mandate fore a prototype "black box" interface was pur from the Office of Special Education (formerly the chased from the Nebraska Videodisc Group at the Bureau of Education for the Handicapped) to dis Nebraska Educational Television Network. -

The Educators' Handbook to Interactive Videodisc. INSTITUTION Association for Educational Communications and Technology, Washingtem, D.C

ED 273 253 IR 012 253 AUTHOR Schwartz, Ed TITLE The Educators' Handbook to Interactive Videodisc. INSTITUTION Association for Educational Communications and Technology, Washingtem, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-89240-049-8 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 101p. AVAILABLE FROM Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 1126 16th Street NW, Washington, DC 20036. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) -- Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from ED2S. DESCRIPTORS Computer Software; *Educational Television; Equipment Maintenance; *Interactive Video; *Videodisks; *Video Equipment ABSTRACT This overview of interactive videodisc techaology is designed to assist educators in finding the appropriate equipment and software for any specific application. The handbook may also serve as a starting point for many educators who know nothing of the technology and assist them in deciding whether this technology is worth pursuing as an educational tool in specific situations. Although not comprehensive, the listings reflect a good portion of the videodisc-related products available today and the prices provide a good indication of the general price range of specific items. The handbook contains 10 chapters: (1) Introduction to Videodiscs; (2) Overview of Laser Disc Systems; (3) Selecting a Laser Videodisc Player; (4) Video Playback Units; (5) Videodisc Interface Units; (6) Disc Player Peripherals; (7) Videodisc System Packages; (8) Educational Videodisc Software; (9) Interactive Videodisc Authoring Languages; and (10) Videodisc Care and Maintenance. Appendices include directories of laser disc players; television monitors and projects; laser disc interfaces; laser disc peripherals; laser disc system packages; videodisc software (listed by subject area); videodisc mastering options; interactive authoring languages; service information; and videodisc resources, which includes a manufacturer's index. -

Pbcore Handbook Section 7

Controlled Vocabularies PBCore Controlled Vocabularies are sets of predefined, community-standardized terms for concepts related to audiovisual and broadcast collections. These terms can be used as drop-down value lists in a database or spreadsheet to ensure consistency in terminology, formatting and spelling, both internally and when exchanging information with outside organizations. PBCore Controlled Vocabularies include the agreed-upon spelling and formatting for each term, a definition, and a Unique Resource Identifier (or URI). The vocabularies provide only the terms that the community has determined are most widely used and shared, and are not 100% comprehensive. PBCore does not maintain controlled vocabularies for elements that have strong vocabulary options maintained by other authorities. Element definitions contain references to relevant external vocabularies, where applicable. pbcoreAssetTypeVocabulary Usage: for pbcoreAssetType Album Definition: A collection of recordings issued as a single item on CD, record, or another medium. URI: http://pbcore.org/pbcore-controlled-vocabularies/pbcoreassettype-vocabulary/#Album Animation Definition: A moving image production element created from static drawings or objects. URI: http://pbcore.org/pbcore-controlled-vocabularies/pbcoreassettype-vocabulary/#Animation Clip Definition: A short excerpt taken from a moving image or audio resource. A clip may not convey a complete intellectual concept. URI: http://pbcore.org/pbcore-controlled-vocabularies/pbcoreassettype-vocabulary/#Clip Collection Definition: A group of materials with some unifying characteristic. – 2. Materials assembled by a person, organization, or repository from a variety of sources; an artificial collection. URI: http://pbcore.org/pbcore-controlled-vocabularies/pbcoreassettype-vocabulary/#Collection Compilation Definition: A single asset containing multiple different sub-assets; for example, a reel with programs, clips, and raw footage. -

DVD) for the Storage of Digital Photolog Images in Connecticut

Development and Implementation of Digital Versatile Disc (DVD) for the Storage of Digital Photolog Images In Connecticut Prepared by: Drew M. Coleman July 2001 Research Project SPR-2224 Report No. 2224-F-01-2 Connecticut Department of Transportation Bureau of Engineering and Highway operations Division of Research Keith R. Lane, P.E. Director of Research and Materials James M. Sime, P.E. Manager of Research Technical Report Documentation Page 1.Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipients Catalog No. FHWA-CT-RD 2224-F-01-2 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date July 2001 Development and Implementation of Digital Versatile Disc (DVD) for the Storage of 6. Performing Organization Code Digital Photolog Images in Connecticut SPR-2224 7. Author(s) Drew M. Coleman 8. Performing Organization Report No. SPR-2224 9. Performing Organization Name and 10. Work Unit No. (TRIS) Address Connecticut Department of Transportation 11. Contract or Grant No. Division of Research CT Study No. SPR-2224 280 West Street Rocky Hill, CT 06067-3502 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Final Report 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address February 1999 to Connecticut Department of Transportation July 2001 2800 Berlin Turnpike Newington, CT 06131-7546 14. Sponsoring Agency Code SPR-2224 15. Supplementary Notes A study conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. 16. Abstract This study addresses all aspects of the application of digital versatile disc (DVD) and related digital imaging technologies as they apply to the storage and retrieval of Photolog images. Additionally, this study outlines the implementation of DVD-based workstations and network-based Photolog servers to replace the analog optical laser videodiscs, which had been the primary Photolog image storage media in Connecticut. -

Pip Lau-Ren-Son

Pip LaurenLaurenrensonson THE CONCONSERSERSERVAVAVATIONTION AND DOCDOCUUUMENMENMENTATATATIONTION OF VIDEO ART* At the Tate Gallery, London, we have developed a special approach to the conservation of video art works (some general guidelines are given in Appendix I). Most of the conservation literature relat- ing to video has been written for archives and those responsible for vast collections of material. Although information about the structure of tape, its storage and its deterioration is applicable to any video collection, there are important differences between the care of art works and the care of archive material. The focus of this article is the conservation of video as art. The Tate’s collection of video is small and recent. Although we own three videos from 1972 by Gil- bert and George, the majority of art works in this medium were made and acquired in the last six years from living artists. In most cases the artist can therefore be involved in the conservation pro- cess. There are three categories in which video is represented at the Tate: 1. As part of an installation that incorporates many different materials of which video is just one ele- ment. For example Matthew Barney’s Ottoshaft is an installation combining a variety of materials including vinyl, tapioca and plastics alongside video. 2. As the primary medium where the equipment and display specifications are essential to the impact and meaning of the sculpture. For example Gary Hill’s Between Cinema and a Hard Place, which includes twenty-three monitors of various sizes, modified by the artist and laid out in a par- ticular way, displaying a series of images. -

Designing an Interactive Videodisc System Network for Effective Training Managem

1986 (23rd) Developing Space For Tomorrow's The Space Congress® Proceedings Society Apr 1st, 8:00 AM Designing an Interactive Videodisc System Network for Effective Training Managem Robert S. Carper Technical Systems Consultant HoneyweI I Federal Systems Division McLean, Virginia Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings Scholarly Commons Citation Carper, Robert S., "Designing an Interactive Videodisc System Network for Effective Training Managem" (1986). The Space Congress® Proceedings. 3. https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings/proceedings-1986-23rd/session-2/3 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Space Congress® Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DESIGNING AN INTERACTIVE VIDEODISC SYSTEM NETWORK FOR EFFECTIVE TRAINING MANAGEMENT Robert S. Carper Technical Systems Consultant HoneyweI I Federal Systems Division McLean, Virginia Abstract Yet, the traditional mode of Instruction del ivery eyebalI to eyebalI has Within the past two years, there has been survived three generations of computer a breakthrough In Interactive videodisc technology, despite some significant training systems technology that has been inroads the computer has made In the made possible through the personal now-recognized field called Computer Based computer. This has resulted In many Training (CBT). A number of Initial companies and Individuals entering the attempts to administer lessons to students field, both in the development of computer have been made via programmed learning hardware and software as welI as the techniques. Still other attempts have preparation of Interactive videodisc been made to manage the volume and types authoring languages and courseware. -

Digital Versatile Disc (DVD): the New Medium for Interactive Video

Michael D. Bush Digital Versatile Disc (DVD): The New Medium for Interactive Video Michael D. Bush Brigham Young University ABSTRACT Interactive video has seemed to have significant promise for improving learning in schools since the 1970s but never reached its maximum poten- tial in foreign language instruction. Digital Versatile Disc (DVD) now appears poised to make this potential a reality. After a relatively difficult beginning, DVD videos are being made increasingly available as major producers are starting to commit to this new format. After reviewing tech- nical and legal issues surrounding the use of DVD, the writer describes authoring possibilities that, although initially complex, can simplify the ultimate delivery of interactive video materials to language learners. Fi- nally, he concludes the article by detailing the process of creating a DVD title in a case study at Brigham Young University. KEYWORDS Digital Versatile Disc (DVD), Interactive Video (IAV), Foreign Language Movies, Technical Considerations, Authoring INTRODUCTION Since the late 1970s interactive video (IAV) instruction has seemed to hold promise for improving learning in schools. Today Digital Versatile Disc (DVD) technology appears poised to make this promise of IAV a reality in education.1 To understand the potential of IAV for learning, consider that some 20 years ago individuals with the WICAT Education Institute conducted a study that began in 1979 and that demonstrated that interactive video could play a significant role in education. This study specifically examined videodisc use for teaching freshman biology at a community college as © 2000 CALICO Journal Volume 17 Number 3 453 Digital Versatile Disc (DVD) well as at a four-year university and found that students learned more, in less time, and with significantly better attitudes toward the subject matter (Bunderson, Olsen, Baillio, Lipson, & Fisher, 1981, 1984). -

Computer Videodisc Education Systems

Computer videodisc education systems Raden Dunbar Executive Officer Satellite and Telecommunications Association Introduction Discussions about the likely widespread use of videodiscs in systems of educational technology have until now tended to focus on the fact that the present generation of disc systems are non-erasable. The grooves and pits moulded or encoded into the surfaces of, respectively, capacitive and optical videodiscs cannot be reconstituted as part of a re-recording process. Any alteration of program content or sequence involves creation of a new master tape from which a new batch of discs must be manufactured. Educationists normally require an instructional medium which can be modified easily and cheaply in the process of regular content evaluations. The blackboard, for example, has this sort of flexibility. Thus far, the complexity and cost of videodisc reprocessing has been regarded as one of the major barriers to its future wide use. However, the educational potential of videodisc is enormous, even revolutionary, as I shall elaborate in this paper. It enables computer directed delivery via television screen of alphanumeric, audio, graphic, still picture, and moving picture information randomly accessed from very large data bases. Depending on the design complexity of video and computer programming, this can be done in an almost endless variety of sequences and overlays. It combines in the one integrated system practically all print and nonprint educational technologies so far devised, and provides the foundations for a truly individualised random-branching system of interactive instruction. The development, proliferation and refinement in the United States Japan, and Europe of new microelectronic devices for processing information is an industrial phenomenon which appears to have no bounds It comes as no surprise then to read of the May 1983 announcement by Matsushita Electric Industrial Company (O'Brien 1983:17: Williams, N. -

RCA Corporation Collection of Television and Company History Photographs and Audiovisual Materials 2464.78

RCA Corporation collection of television and company history photographs and audiovisual materials 2464.78 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library RCA Corporation collection of television and company history photographs and audiovisual materials 2464.78 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 8 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

Cataloging Video Recordings in RDA: MARC Fields ‐ 1

Cataloging Video Recordings in RDA: MARC Fields ‐ 1 MARC Field MARC Field Indica‐ Data recorded Note RDA Rule(s) Tag tors Leader/06 Type: Type of record g Projected medium Leader/07 BLvl: Bibliographical m Monograph/item record VIS:008/29; Form: Form of item q Direct electronic (for CD‐ROM, 006/12 DVD‐ROM) VIS:008/33; TMat: Type of Material v Videorecording 006/16 VIS:008/34; Tech: Technique a Animation 006/17 c Animation and live action l Live action z Other 007/00 Physical description / $a v Videorecording Category of material 007/01 Physical description / $b d Videodisc Specific material $b f Videocassette designation 007/03 Physical description / $d b Black & white Color $d c Multicolored 007/04 Physical description / $e b VHS Videorecording format $e s Blu‐ray disc $e v DVD 007/05 Physical description / $f a Sound on medium Sound on medium or separate 007/06 Physical description / $g h Videotape Medium for sound $g i Videodisc 007/07 Physical description / $h o 1/2 in. (VHS) Dimensions $h z Other (DVD, Blu‐Ray) 007/08 Physical description / $i k Mixed Configuration of $i m Monaural playback channels $i q Quadraphonic, multichannel, or surround $i s Stereophonic $i u Unknown (not stated) Cataloging Video Recordings in RDA: MARC Fields ‐ 2 020 International Standard $a ISBN 2.15 Book Number (ISBN) 024 Other standard 0 # $a International Standard Recording Code ISRC 2.15 identifier 1 # $a Universal Product Code UPC (10 or 13 digits) 3 # $a International Article Number EAN (13 digits, 1st indicator 3) 028 Publisher number 4 2 $a Videorecording -

Optical Disc Storage: Another Can of Worms?

25 Optical disc storage: another can of worms? Roger Martlew Department of Archaeology, University of Leicester 25.1 Introduction The University Grants Committee and the Computer Board have funded 139 projects in Bntish Umversities as part of their Computers in Teaching Initiative. Two projects have been accepted m archaeology, a joint Southampton/York project on simulating an excavation and an mvestigation at Leicester into the use of interactive videodiscs for teaching archaeology to undergraduates. This paper introduces the work which has just started at Leicester University, in the wider context of the potential application of optical storage devices in archaeology. The paper is also an mvitation to submit databases of visual material, on any archaeological subject, for possible mclusion on the videodisc which is being produced as part of the project. 25.2 How optical storage tectinology works Videodiscs are one manifestation of optical storage technology. The basic principle of these systems is that digital data are stored as microscopic pits in the reflective surface of a disc m either concentric tracks or in a spiral track as on a record. When a low-powered laser is' directed along these tracks on a spinning disc, the pits interrupt the reflection from the disc suri-ace aUowing the data to be read. The commonest example of optical disc storage is the compact audio disc, known as CD-Audio: the digital data read from the disc are converted into music. If tiiis conversion stage is omitted, data from the disc can be read straight into a computer. The disc then provides a high-density storage medium, and is known as CD-ROM (Compact Disc Read Only Memory).