Digital Versatile Disc (DVD): the New Medium for Interactive Video

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLU-BD3000 User Manual

BLU-BD3000 User Manual 0 | P a g e BLU-BD3000 User Manual Contents Safety Notice and Important Information 2 Media Compatibility 4 Incompatible Media 5 Region Information 5 Player & Disk Case 6 Getting to know your BLU-BD3000 player 7 What’s in the box 7 The Front and Rear panels 7 Using the Remote Control 8 Connection your BLU-BD3000 Player 11 Internet/Network connection 15 Connecting a USB Device 16 Playing a Disk 17 On Screen Control (OSC Button) 18 BD-Live 21 DLNA Network Media Player 25 Setup & Settings 27 General 27 Display 33 Audio 36 System Information 38 Programming a Disc 39 Media Centre – USB Playback 39 FAQ 43 Specifications 46 1 | P a g e BLU-BD3000 User Manual Safety Notice and Important Information Please read the instructions carefully before using this product Observe all warnings and cautions when using this product. Retain all manuals and documentation for future referral. Only use this product in the manner described in this manual. Do not use this device in extremely hot, cold, humid, dusty or sandy environments. Do not use this device in electrical storms or other conditions if the likely hood of lightning is possible. Do not attempt to clean this product using liquid cleaners or aerosol cleaners. Use only a damp soft cloth to clean the surface of this device. This device may become hot during use. Do not cover vent holes and place in a well-ventilated area. This device is not waterproof. Do not use this device in the open if there is a high level of moisture in the air. -

R5505 DVD/CD/MP3 Player W/ TV Tuner R5506 DVD/CD/MP3 Player

ROSEN a anew new generation generation of of leadership leadership in mobile in mobilevideo video R5505 DVD/CD/MP3 Player w/ TV Tuner R5506 DVD/CD/MP3 Player Owner's Manual and Installation Guide R .mp3 R T Warning! Table of Contents THE R5505/R5506 DVD/CD/MP3 PLAYERS ARE DESIGNED TO Introduction ...................................................................... 2 ENABLE VIEWING OF DVD OR CD-VIDEO RECORDINGS ONLY FOR REAR-SEAT OCCUPANTS. Care and Maintenance ..................................................... 3 MOBILE VIDEO PRODUCTS ARE NOT INTENDED FOR VIEW- Discs Played by this unit ................................................... 4 ING BY THE DRIVER WHILE THE VEHICLE IS IN MOTION. SUCH USE MAY DISTRACT THE DRIVER OR INTERFERE WITH Using the DVD player ........................................................ 5 THE DRIVER’S SAFE OPERATION OF THE VEHICLE, AND THUS RESULT IN SERIOUS INJURY OR DEATH. SUCH USE MAY ALSO VIOLATE STATE LAW. The Remote Control .......................................................... 7 ROSEN ENTERTAINMENT SYSTEMS DISCLAIMS ANY LIABIL- DVD/VCD/CD-Audio Playback .......................................... 8 ITY FOR ANY BODILY INJURY OR PROPERTY DAMAGE THAT MAY RESULT FROM ANY IMPROPER OR UNINTENDED USE. Watching Broadcast Television (R5505 only)................. 10 MP3 Playback on CD-R discs .......................................... 11 About Installation Installation of mobile audio and video components requires Installation and Wiring .................................................... 12 experience -

Store up to 8.5Gb on One Disc Lightscribe Disc Labeling

STORE UP TO 8.5GB ON ONE DISC - With double layer DVD recording technology, the LaCie Slim DVD±RW Drive with LightScribe, Design by F.A. Porsche can be used to store nearly twice as much data as before. With up to 8.5GB of space on a single-sided, double layer DVD disc, save up to 16 hours of VHS video, 4 hours of personal, high-quality DVD video or up to 8.5GB of important data. Large-capacity, double layer DVD media is also ideal for backing up computer systems or saving thousands of MP3s. LIGHTSCRIBE DISC LABELING This drive is now equipped with LightScribe—an innovative technology that allows you to burn silkscreen-quality labels directly onto CDs* and DVDs* with a laser instead of a printer. LightScribe uses a combination of your CD/DVD drive, specially coated discs, and enhanced disc-burning software to produce precise, professional labels. The result is an impressive iridescent image composed of art, text, or photos of your own creation. BROAD CD AND DVD COMPATIBILITY Conveniently compatible with DVD+R/RW and DVD-R/RW media •Burn customized 8.5GB and virtually all DVD players, the LaCie Slim DVD±RW Drive with video DVDs LightScribe, Design by F.A. Porsche lets you choose the format you’d •Store photos, MP3s and like to use. With the ability to store digital data on DVD or CD media, videos on your discs this all-in-one drive accommodates a variety of multimedia jobs. This • Bundled with Easy Media rewritable drive can be connected to any PC. -

CD/DVD Player

4-277-895-11(1) CD/DVD Player Operating Instructions DVP-NS638P DVP-NS648P © 2011 Sony Corporation Precautions Notes about the discs Safety • To keep the disc clean, handle WARNING To prevent fire or shock hazard, do the disc by its edge. Do not touch not place objects filled with the surface. Dust, fingerprints, or To reduce the risk of fire or liquids, such as vases, on the scratches on the disc may cause electric shock, do not expose apparatus. it to malfunction. this apparatus to rain or moisture. Installing To avoid electrical shock, do • Do not install the unit in an not open the cabinet. Refer inclined position. It is designed servicing to qualified to be operated in a horizontal personnel only. position only. The mains lead must only be • Keep the unit and discs away changed at a qualified from equipment with strong service shop. magnets, such as microwave Batteries or batteries ovens, or large loudspeakers. installed apparatus shall not • Do not place heavy objects on be exposed to excessive heat the unit. such as sunshine, fire or the like. Lightning For added protection for this set • Do not expose the disc to direct CAUTION during a lightning storm, or when it sunlight or heat sources such as is left unattended and unused for hot air ducts, or leave it in a car The use of optical instruments with long periods of time, unplug it parked in direct sunlight as the this product will increase eye from the wall outlet. This will temperature may rise hazard. As the laser beam used in prevent damage to the set due to considerably inside the car. -

Use External Storage Devices Like Pen Drives, Cds, and Dvds

External Intel® Learn Easy Steps Activity Card Storage Devices Using external storage devices like Pen Drives, CDs, and DVDs loading Videos Since the advent of computers, there has been a need to transfer data between devices and/or store them permanently. You may want to look at a file that you have created or an image that you have taken today one year later. For this it has to be stored somewhere securely. Similarly, you may want to give a document you have created or a digital picture you have taken to someone you know. There are many ways of doing this – online and offline. While online data transfer or storage requires the use of Internet, offline storage can be managed with minimum resources. The only requirement in this case would be a storage device. Earlier data storage devices used to mainly be Floppy drives which had a small storage space. However, with the development of computer technology, we today have pen drives, CD/DVD devices and other removable media to store and transfer data. With these, you store/save/copy files and folders containing data, pictures, videos, audio, etc. from your computer and even transfer them to another computer. They are called secondary storage devices. To access the data stored in these devices, you have to attach them to a computer and access the stored data. Some of the examples of external storage devices are- Pen drives, CDs, and DVDs. Introduction to Pen Drive/CD/DVD A pen drive is a small self-powered drive that connects to a computer directly through a USB port. -

Nerovision Express 3

User's Guide NeroVision Express 3 Bringing the world of video closer to home - Creating your very own DVD, VCD, SVCD and miniDVD Nero AG Copyright and Trademark Information The NeroVision Express 3 User's Guide and the NeroVision Express 3 Software are copyrighted and the property of Nero AG, Im Stoeckmaedle 18, 76307 Karlsbad, Germany. All rights are reserved. This Quick Start Guide contains materials protected under International Copyright Laws. It is expressly forbidden to copy, reproduce, duplicate or transmit all or any part of the Guide or the software without the prior written consent of Nero AG. All brand names and trademarks are properties of their respective owners. THIS MANUAL IS PROVIDED 'AS IS,' AND NERO AG MAKES NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, NON-INFRINGEMENT, OR TITLE; THAT THE CONTENTS OF THE MANUAL ARE SUITABLE FOR ANY PURPOSE; NOR THAT THE IMPLEMENTATION OF SUCH CONTENTS WILL NOT INFRINGE ANY THIRD PARTY PATENTS, COPYRIGHTS, TRADEMARKS OR OTHER RIGHTS. NERO AG WILL NOT BE LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, SPECIAL OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES ARISING OUT OF ANY USE OF THE MANUAL OR THE PERFORMANCE OR IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONTENTS THEREOF. The name and trademarks of Nero AG may NOT be used in advertising or publicity pertaining to this manual or its contents without specific written prior permission. Title to copyright in this manual will at all times remain with Nero AG. Nero AG accepts no claims for the correctness of the contents of the manual. -

CLD-D704 Mllm=Wql L Il 'Ily ,, L DIGITAL AUDIO L a SER D/SC

CD CDV LD PLAYER I R=..,'.,_,_,=. CLD-D704 Mllm=Wql_l il_'ilY_ ,, L DIGITAL AUDIO L A SER D/SC • This player does not apply to business use. • CD-ROM, LD-ROM and CD graphic discs cannot be played with this player. F_y_IIE_I31 _e. CLD 704 _-,, .B3_i!I ._',-.r4-_ _!, ____ _ i I, .I Thank you for buying this Pioneer product. Please read through these operating instructions so you will know how to operate your model properly. After you have finished reading the instructions, put them away in a safe place for future reference. In some countries or regions, the shape of the power plug and power outlet may sometimes differ from that shown in the explanatory drawings. However, the method of connecting and operating the unit is the same. WARNING: TO PREVENT FIRE OR SHOCK HAZARD, CAUTION: DO NOT EXPOSE THIS APPLIANCE TO RAIN OR This product satisfies FCC regulations when shielded MOISTURE. cables and connectors are used to connect the unit to other equipment. To prevent electromagnetic interference with IMPORTANT NOTICE electric appliances such as radios and televisions, use shielded cables and connectors for connections. [For U.S. and Canadian models] The serial number for this equipment is located on the rear panel. Please write this serial number on your enclosed warranty card and keep it in a secure area. This is for your security. [For Canadian model] CAUTION: TO PREVENT ELECTRIC SHOCK DO NOT USE THIS (POLARIZED) PLUG WITH AN EXTENSION CORD, RECEPTACLE OR OTHER OUTLET UNLESS THE EXPOSURE. ATTENTION: POUR PREVENIR LES CHOCS ELECTRIOUES NE PAS UTILISER CETTE FICHE POLARISEF AVEC UN PROLONGATEUR, UNE PRISE DE COURANT OU UNE AUTRE SORTIE DE COURANT, SAUF SI LES LAMES PEUVENT ETRE INSEREES A FOND SANS EN LAISSER AUCUNE PARTIE A DECOUVERT. -

DVP3650/51 Philips DVD Player

Philips 3000 series DVD player DVP3650 Enjoy it all - from DVD Does size matter? Ever heard of less is more? Introducing the best value DVD player. No complications! Just a simple set that plays practically any disc format, including your digital photos with absolutely no compromise to picture quality. Bring audio and video to life • 12-bit/108MHz video processing for sharp and natural images • 192kHz/24 bit audio DAC enhances analogue sound input • Progressive Scan component video for optimized image quality • Screen Fit for optimal viewing every time Play all your movies and music • ProReader Drive for smooth playback on virtually any disc • DivX Ultra Certified for enhanced DivX video playback • Play CD, (S)VCD, DVD, DVD+- R/RW, DivX, MP3, WMA, JPEG Connect and enjoy multiple sources • USB Media Link for media playback from USB flash drives DVD player DVP3650/51 Highlights ProReader Drive colors, resulting in a more vibrant and natural DivX Ultra Certified picture. The limitation of the usual 10bit DAC become in particular apparent while using large screens and projectors. 192kHz/24 bit audio DAC ProReader Drive lets you enjoy your movies With DivX support, you are able to enjoy and videos worry-free. Even when old discs get DivX encoded videos and movies from the smudgy or scratched, you can rest assured that Internet, including purchased Hollywood films, they will play right through from start to end - in the comfort of your living room. The DivX without any sign that they have been damaged. media format is an MPEG-4 based video Using state-of-the-art technology, ProReader 192KHz sampling enables you to have an compression technology that enables you to Drive converts weak analog signals into robust accurate representation of the original sound save large files like movies, trailers and music digital ones, extracting information that allows curves. -

Audio/Video/PC: Hauptabt

Return to: For passing on to and Messe München GmbH invoicing by Audio/Video/PC: Hauptabt. Gahrens + Battermann GmbH Techn. Ausstellerservice 13.1 Unterhachinger Strasse 75 Gahrens + Battermann Messegelände 81737 München, Germany Submit in duplicate 81823 München Phone +49 (0) 89 61 45 57-0 Page 1 of 3 Germany Fax +49 (0) 89 61 45 57-57 Office during the fair: Atrium, in front of Hall B4 Event: ESC Congress 2008 Phone +49 (0) 89 949 - 2 49 15 Closing date: 4 July 2008 Date: 30 August – 3 September 2008 Exhibitor Hall Stand no. Contact Street/P.O.Box Phone with area code and ext. Fax with area code and ext. Country, Town, Postcode E-mail All prices quoted are in euro and include costs for rental, transport, set-up and dismantling. Prices do not include VAT. Rental service for audio, video, data applications and computers: Item Plasma monitors 1 day 3 days 4 days 5 days 6 days 7 days 9 days 01 42” / 106.7 cm plasma 16:9, video/data, incl. speakers and floor stand or wall support 360.00 535.00 610.00 665.00 705.00 735.00 795.00 02 50” / 127.0 cm plasma 16:9, video/data, incl. speakers and floor stand or wall support, HDready 425.00 695.00 805.00 885.00 945.00 990.00 1,075.00 03 61”/ 155.0 cm plasma 16:9, video/data, incl. speakers and floor stand or wall support, HDready 665.00 1,090.00 1,275.00 1,405.00 1,495.00 1,570.00 1,720.00 04 65”/ 165.1 cm plasma 16:9, video/data, incl. -

RDA -- Content, Media, and Carrier Type Values for Various Types Of

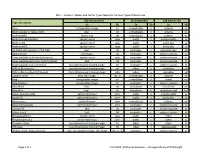

RDA -- Content, Media, and Carrier Type Values for Various Types of Resources 336 (rdacontent) 337 (rdamedia) 338 (rdacarrier) Type of resource $a $b $a $b $a $b Atlas cartographic image cri unmediated n volume nc Book (regular or large print) text txt unmediated n volume nc Book (braille) tactile text txt unmediated n volume nc Book on audiocassette spoken word spw audio s audiocassette ss Book on CD spoken word spw audio s audio disc sd Book on MP3 spoken word spw audio s audio disc sd CD-ROM with text (e.g., PDF files) text txt computer c computer disc cd Digital image still image sti computer c online resource cr Downloadable audio book (e-audio) spoken word spw computer c online resource cr Downloadable electronic book (e-book) text txt computer c online resource cr Downloadable video (e-video) two-dimensional moving image tdi computer c online resource cr DVD or Blu-ray disc two-dimensional moving image tdi video v videodisc vd DVD or Blu-ray disc (3-D movie) three-dimensional moving image tdm video v videodisc vd Graphic novel text, still image txt, sti unmediated n volume nc Map cartographic image cri unmediated n sheet nb Map (online) cartographic image cri computer c online resource cr Microfiche text txt microform h microfiche he Microfilm text txt microform h microform reel hd Music audiocassette performed music prm audio s audiocassette ss Music CD performed music prm audio s audio disc sd Music score notated music ntm unmediated n volume nc Music (streaming) performed music prm computer c online resource cr Online PDF text txt computer c online resource cr Online serial text txt computer c online resource cr Playaway (book) spoken word spw audio s other sz Playaway (music) performed music prm audio s other sz Playaway View two-dimensional moving image tdi video v other vz VHS tape two-dimensional moving image tdi video v videocassette vf Website (text, maps, photos) text, cartographic image, still image txt, cri, sti computer c online resource cr Page 1 of 1 4/13/2013 (Cathy Lamoureaux -- Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh). -

You Need to Know About CD And

All you need to know about CDs and DVDs Table of Contents [1] Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 [1.1] What is the difference between Replication and Duplication?........................................................ 3 [2] What are all the available media formats? ............................................................................................. 3 [2.1] CD-ROM Formats .............................................................................................................................. 3 [2.1.1] Audio CD .................................................................................................................................... 4 [2.1.2] Audio CD with Data ................................................................................................................... 4 [2.1.3] Video CD (VCD) , Super VCD (SVCD) .......................................................................................... 4 [2.1.4] Video CD with Data .................................................................................................................... 4 [2.1.5] Data CD ...................................................................................................................................... 4 [2.1.6] Hybrid CD ................................................................................................................................... 4 [2.2] DVD Formats .................................................................................................................................... -

"Think It Through": an Interactive Videodisc for the Hearing Impaired

"THINK IT THROUGH": AN INTERACTIVE VIDEODISC FOR THE HEARING IMPAIRED Casey Garhart Stone and Gwen C. Nugent Media Development Project for the Hearing Impaired Lincoln, Neb. disc player with an external microcomputer. In this way the realistic, high quality visuals of the videodisc could join with the memory and branching capabili ties of the computer to provide the hearing impaired with an interactive and individualized visual com munication medium. The project used an MCA DiscoVision 7820 video disc player and a Radio Shack TRS-80 microcomput er to achieve this union of technologies. An IEEE port, a standard feature of the 7820 player, allows easy access for a two-way interface between the videodisc and the computer. Basically, the computer can be programmed to operate the player, and the player can indicate to the computer when it has exe Casey G. Stone Gwen C. Nugent cuted one command and is ready for the next. Unfortunately, this interface requires two moni tors because of the incompatibility of the two video The feasibility of interfacing a videodisc player signals. One monitor displays the videodisc picture, with an external microcomputer is discussed. while the other displays the computer graphics. For a young audience, and owing to the complex nature of From 1978 through 1980, the Media Development the proposed disc, it was determined that the double Project for the Hearing Impaired (MDPHI) at the monitor approach would be ill-advised, and there University of Nebraska worked under a mandate fore a prototype "black box" interface was pur from the Office of Special Education (formerly the chased from the Nebraska Videodisc Group at the Bureau of Education for the Handicapped) to dis Nebraska Educational Television Network.