“Let Our Freak Flags Fly”: Shrek the Musical and the Branding of Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek4 Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. ESRB Game Ratings The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) ratings are designed to provide consumers, especially parents, with concise, impartial guidance about the age- appropriateness and content of computer and video games. This information can help consumers make informed purchase decisions about which games they deem suitable for their children and families. -

Shrek the Musical Study Guide

The contents of this study guide are based on the National Educational Technology Standards for Teachers. Navigational Tools within this Study Guide Backward Forward Return to the Table of Contents Many pages contain a variety of external video links designed to enhance the content and the lessons. To view, click on the Magic Mirror. 2 SYNOPSIS USING THE LESSONS RESOURCES AND CREDITS TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 BEHIND THE SCENES – The Making of Shrek The Musical Section 2 LET YOUR FREAK FLAG FLY Section 2 Lessons Section 3 THE PRINCE AND THE POWER Section 3 Lessons Section 4 A FAIRY TALE FOR A NEW GENERATION Section 4 Lessons Section 5 IT ENDS HERE! - THE POWER OF PROTEST Section 5 Lessons 3 Act I Once Upon A Time. .there was a little ogre named Shrek whose parents sat him down to tell him what all little ogres are lovingly told on their seventh birthday – go away, and don’t come back. That’s right, all ogres are destined to live lonely, miserable lives being chased by torch-wielding mobs who want to kill them. So the young Shrek set off, and eventually found a patch of swampland far away from the world that despised him. Many years pass, and the little ogre grows into a very big ogre, who has learned to love the solitude and privacy of his wonderfully stinky swamp (Big Bright Beautiful World.) Unfortunately, Shrek’s quiet little life is turned upside down when a pack of distraught Fairy Tale Creatures are dumped on his precious land. Pinocchio and his ragtag crew of pigs, witches and bears, lament their sorry fate, and explain that they’ve been banished from the Kingdom of Duloc by the evil Lord Farquaad for being freakishly different from everyone else (Story Of My Life.) Left with no choice, the grumpy ogre sets off left to right Jacob Ming-Trent to give that egotistical zealot a piece of his mind, and to Adam Riegler hopefully get his swamp back, exactly as it was. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Tese De Charles Ponte

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM CHARLES ALBUQUERQUE PONTE INDÚSTRIA CULTURAL, REPETIÇÃO E TOTALIZAÇÃO NA TRILOGIA PÂNICO Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem, da Universidade Estadual de Campinas, para obtenção do Título de Doutor em Teoria e História Literária, na área de concentração de Literatura e Outras Produções Culturais. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fabio Akcelrud Durão CAMPINAS 2011 i FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA POR CRISLLENE QUEIROZ CUSTODIO – CRB8/8624 - BIBLIOTECA DO INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM - UNICAMP Ponte, Charles, 1976- P777i Indústria cultural, repetição e totalização na trilogia Pânico / Charles Albuquerque Ponte. -- Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2011. Orientador : Fabio Akcelrud Durão. Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. 1. Craven, Wes. Pânico - Crítica e interpretação. 2. Indústria cultural. 3. Repetição no cinema. 4. Filmes de horror. I. Durão, Fábio Akcelrud, 1969-. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. III. Título. Informações para Biblioteca Digital Título em inglês: Culture industry, repetition and totalization in the Scream trilogy. Palavras-chave em inglês: Craven, Wes. Scream - Criticism and interpretation Culture industry Repetition in motion pictures Horror films Área de concentração: Literatura e Outras Produções Culturais. Titulação: Doutor em Teoria e História Literária. Banca examinadora: Fabio Akcelrud Durão [Orientador] Lourdes Bernardes Gonçalves Marcio Renato Pinheiro -

SHREK the MUSICAL Official Broadway Study Guide CONTENTS

WRITTEN BY MARK PALMER DIRECTOR OF LEARNING, CREATIVE AND MEDIA WIldERN SCHOOL, SOUTHAMPTON WITH AddITIONAL MATERIAL BY MICHAEL NAYLOR AND SUE MACCIA FROM SHREK THE MUSICAL OFFICIAL BROADWAY STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Welcome to the SHREK THE MUSICAL Education Pack! A SHREK CHRONOLOGY 4 A timeline of the development of Shrek from book to film to musical. SynoPsis 5 A summary of the events of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Production 6 Interviews with members of the creative team of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Fairy Tales 8 An opportunity for students to explore the genre of Fairy Tales. Feelings 9 Exploring some of the hang-ups of characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. let your Freak flag fly 10 Opportunities for students to consider the themes and characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. One-UPmanshiP 11 Activities that explore the idea of exaggerated claims and counter-claims. PoWer 12 Activities that encourage students to be able to argue both sides of a controversial topic. CamPaign 13 Exploring the concept of campaigning and the elements that make a campaign successful. Categories 14 Activities that explore the segregation of different groups of people. Difference 15 Exploring and celebrating differences in the classroom. Protest 16 Looking at historical protesters and the way that they made their voices heard. AccePtance 17 Learning to accept ourselves and each other as we are. FURTHER INFORMATION 18 Books, CD’s, DVD’s and web links to help in your teaching of SHREK THE MUSICAL. ResourceS 19 Photocopiable resources repeated here. INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Education Pack for SHREK THE MUSICAL! Increasingly movies are inspiring West End and Broadway shows, and the Shrek series, based on the William Steig book, already has four feature films, two Christmas specials, a Halloween special and 4D special, in theme parks around the world under its belt. -

In the Service of Others: from Rose Hill to Lincoln Center

Fordham Law Review Volume 82 Issue 4 Article 1 2014 In the Service of Others: From Rose Hill to Lincoln Center Constantine N. Katsoris Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constantine N. Katsoris, In the Service of Others: From Rose Hill to Lincoln Center, 82 Fordham L. Rev. 1533 (2014). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol82/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEDICATION IN THE SERVICE OF OTHERS: FROM ROSE HILL TO LINCOLN CENTER Constantine N. Katsoris* At the start of the 2014 to 2015 academic year, Fordham University School of Law will begin classes at a brand new, state-of-the-art building located adjacent to the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. This new building will be the eighth location for Fordham Law School in New York City. From its start at Rose Hill in the Bronx, New York, to its various locations in downtown Manhattan, and finally, to its two locations at Lincoln Center, the law school’s education and values have remained constant: legal excellence through public service. This Article examines the law school’s rich history in public service through the lives and work of its storied deans, demonstrating how each has lived up to the law school’s motto In the service of others and concludes with a look into Fordham Law School’s future. -

Recommended Talking Points

RECOMMENDED TALKING POINTS “What is SHREK THE MUSICAL?” The official title of the show is SHREK THE MUSICAL. SHREK THE MUSICAL is an entirely new musical based on the story and characters from William Steig’s book Shrek!, as well as the Oscar® winning DreamWorks Animation film Shrek, the first chapter of the Shrek movie series. SHREK THE MUSICAL looks backwards at all the fairy tale traditions we grew up on: a hero (a big, green, ill-tempered ogre), a beautiful princess (who is not all she appears to be), and a dastardly villain (with some obvious shortcomings) and takes great fun turning all their storytelling conventions upside-down and inside-out (and on their ear). “How did the musical come about?” Sam Mendes, the British director and producer, was a big fan of the first film, and he suggested the idea of creating a musical to DreamWorks’ Jeffrey Katzenberg, around the time the second film was in production. Now, the musical is being produced by DreamWorks Theatricals (Bill Damaschke, President) and Neal Street Productions, Ltd (principals Sam Mendes and Caro Newling). “How does the new musical fit into the Shrek pantheon?” The story of the musical follows the events and characters of the first Shrek feature film, which won the first-ever Academy Award® for Best Animated Feature. In SHREK THE MUSICAL, the creative team will go deeper into the background and story of Shrek, Princess Fiona, Donkey and the lovable collection of everyone’s favorite Fairy-Tale characters. SHREK THE MUSICAL will feature a completely original score by one the theatre’s most eclectic composers, Jeanine Tesori, working in theatre today. -

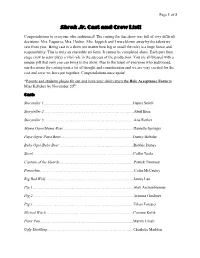

Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List!

Page 1 of 3 Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List! Congratulations to everyone who auditioned! The casting for this show was full of very difficult decisions. Mrs. Esquerra, Mrs. Hosker, Mrs. Joppich and I were blown away by the talent we saw from you. Being cast in a show (no matter how big or small the role) is a huge honor and responsibility. This is truly an ensemble art form. It cannot be completed alone. Each part from stage crew to actor plays a vital role in the success of the production. You are all blessed with a unique gift that only you can bring to the show. Due to the talent of everyone who auditioned, our decisions for casting took a lot of thought and consideration and we are very excited for the cast and crew we have put together. Congratulations once again! *Parents and students please fill out and have your child return the Role Acceptance Form to Miss Kelleher by November 20th. Cast: Storyteller 1……………………………………………………….…..Hanna Smith Storyteller 2………………………………………………………...….Abril Brea Storyteller 3……………………………..……………………..………Ana Rother Mama Ogre/Mama Bear………………………….………………...…Danielle Springer Papa Ogre/ Papa Bear……………………………………………..…Danny Boboltz Baby Ogre/Baby Bear ………………………………...…….………...Robbie Dubay Shrek…………………………………………………………….....….Collin Toole Captain of the Guards………………………………………….…...…Patrick Twomey Pinocchio……………………………………………………………....Colin McCauley Big Bad Wolf………………………………………………….….…....James Lau Pig 1……………………………………………………………….......Alex Aschenbrenner Pig 2…………………………………………………………….…......Arianna Gardiner Pig 3………………………………………………………….......……Ethan -

William Steig Illustrations, Circa 1969 FLP.CLRC.STEIG Finding Aid Prepared by Lindsay Friedman

William Steig illustrations, circa 1969 FLP.CLRC.STEIG Finding aid prepared by Lindsay Friedman This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit April 12, 2012 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Free Library of Philadelphia: Children's Literature Research Collection February 2012 1901 Vine Street Philadelphia, PA, 19103 215-696-5370 William Steig illustrations, circa 1969 FLP.CLRC.STEIG Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... -

“The Secret Silk” with Stephen Schwartz and John Tartaglia Onboard Royal Princess

Princess Cruises Celebrates The Premiere Of “The Secret Silk” With Stephen Schwartz and John Tartaglia Onboard Royal Princess March 1, 2018 FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. (March 1, 2018) – Princess Cruises celebrated the premiere of "The Secret Silk," the newest offering from it's first-of-its-kind partnership with Stephen Schwartz, the Oscar-, Grammy- and Tony Award-winning composer of "Wicked," "Godspell," and "Pippin." Joining Schwartz aboard Royal Princess for the premiere was the Tony Award nominated director/creator John Tartaglia ("Avenue Q," "Shrek"). The Secret Silk is a story of an Asian folkloric tale with a contemporary spin, featuring inspired performances through the use of music, dance, puppetry and special effects. Adapted from the ancient fable "The Grateful Crane," the story features Lan, a beautiful, selfless young woman who possesses a magical gift, secretly creating brilliant silk fabrics. Audiences will be introduced to original life-size puppetry from Jim Henson's Creature Shop, and an original song, "Sing to the Sky," both created exclusively for the production. Overseeing the creative development of four entertainment shows for Princess Cruises, Schwartz brings together an illustrious team of Broadway talent to support the productions through direction and design. "The Secret Silk" is created and directed by Tartaglia and in addition to Royal Princess, will be rolled out on Island Princess for the 2018 summer Alaska season, and Diamond Princess in winter 2018, sailing year-round Japan. Additional creative team talent includes choreography by Shannon Lewis ("Fosse"), scenic design by Tony Award nominee Anna Louizos ("School of Rock"), costumes by Tony Award winner Clint Ramos ("Eclipsed"), and music direction from Brad Ellis ("Glee"). -

Shrek Audition Monologues

Shrek Audition Monologues Shrek: Once upon a time there was a little ogre named Shrek, who lived with his parents in a bog by a tree. It was a pretty nasty place, but he was happy because ogres like nasty. On his 7th birthday the little ogre’s parents sat him down to talk, just as all ogre parents had for hundreds of years before. Ahh, I know it’s sad, very sad, but ogres are used to that – the hardships, the indignities. And so the little ogre went on his way and found a perfectly rancid swamp far away from civilization. And whenever a mob came along to attack him he knew exactly what to do. Rooooooaaaaar! Hahahaha! Fiona: Oh hello! Sorry I’m late! Welcome to Fiona: the Musical! Yay, let’s talk about me. Once upon a time, there was a little princess named Fiona, who lived in a Kingdom far, far away. One fateful day, her parents told her that it was time for her to be locked away in a desolate tower, guarded by a fire-breathing dragon- as so many princesses had for hundreds of years before. Isn’t that the saddest thing you’ve ever heard? A poor little princess hidden away from the world, high in a tower, awaiting her one true love Pinocchio: (Kid or teen) This place is a dump! Yeah, yeah I read Lord Farquaad’s decree. “ All fairytale characters have been banished from the kingdom of Duloc. All fruitcakes and freaks will be sent to a resettlement facility.” Did that guard just say “Pinocchio the puppet”? I’m not a puppet, I’m a real boy! Man, I tell ya, sometimes being a fairytale creature sucks pine-sap! Settle in, everyone. -

Shrek the Musical Cast List

Shrek the Musical Fairy Tale Creatures Cast List Gingy – Adelia Haines Pinocchio – Logan Overturf Big Bad Wolf – Zach Abrams Shrek – James Long Shrek Understudy – Blake Brinsa Three Little Pigs Briksi - Ziona Patterson Youngest Fiona – Straw Baby - Emi Scarlett Abby Zimmerman Styx - Josie Hougham Teen Fiona – Kaylee Peraza Princess Fiona – Miyon Roston White Rabbit – Erica Burnett Ogress Fiona – Fairy Godmother – Sadie Waggerman Madison Bogart Peter Pan – DeSean Harrison Donkey – Jordon Prince Wicked Witch – Aarika Wilson Donkey Understudy – Sugar Plum Fairy – Zach Abrams Madison Coonce Tooth Fairy – Abby Dixon Lord Farquaad – Kyle Villaverde Ugly Duckling – Paige Hutson Lord Farquaad Understudy – Blake Brinsa/Zach Abrams Three Bears Papa Bear - Blake Brinsa Mama Bear – Audrey Resch Dragon – Alyna Mathews Baby Bear - Hunter Murray Dragon Understudy – Madison Coonce Mad Hatter – Derek Walsh Dragonettes Humpty Dumpty - Brimstone – Audrey Resch Quincy Knighten Smokey - Madison Coonce Humpty Dumpty Understudy - Ashley Summers Elf – Makayla Gandara Dwarf – Julien Harrison Three Blind Mice Captain Thelonius – 1. Kristina King Jadin Douglas 2. Alexis Baynon Duloc Guards 3. Molly Bryant 1. Julian Harrison 2. Quincy Jackson Bluebird – Kaylee Peraza 3. Donovan Ortiz 4. Adrian Craigmiles Bishop – Adrian Craigmiles Knights Little Shrek – Liam White 1. Israel Aguilar Mama Ogre – 2. Hunter Murray Delaney Bresnahan 3. Drake Zion Papa Ogre – Tyler Freeman 4. Jadin Douglas King Harold – Donovan Ortiz Queen Lillian – Pied Piper – Rusty Lasiter Sadie Waggerman Pied Piper’s Rats 1. Jaelee Pittel 2. Gavin Davis 3. Bella Rodriguez 4. Natalie Bryant 5. Julian Harrison 6. Kristina King 7. Elva Rodriguez 8. Quincy Jackson Angry Mob Happy People Natalie Bryant Marissa Pendergrast Julien Harrison Drake Zion Cara Emerson Hannah Schoonover Sam Littlecreek Angelina Hess Kristina King Ashley Summers Duloc Performers 1.